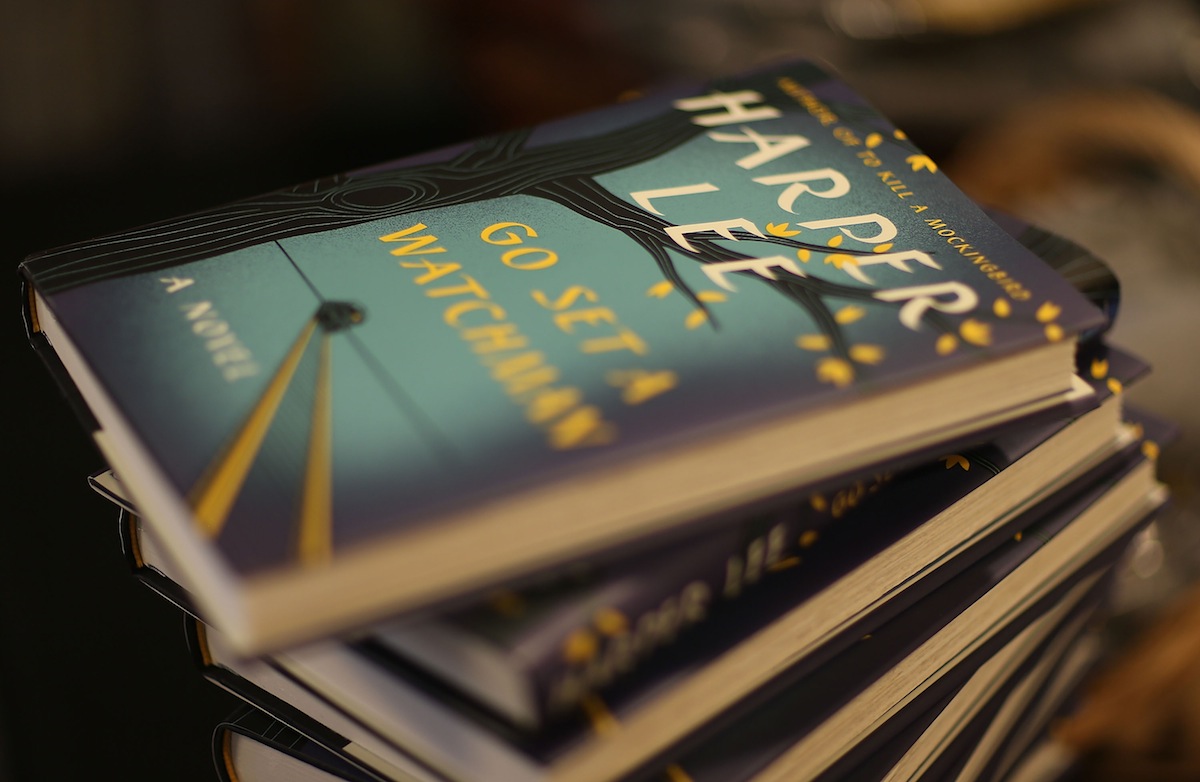

To Kill a Mockingbird was set in the early 1930s, and Harper Lee portrayed Atticus Finch—obviously based on her own father—as a calm, fearless crusader for justice for all, regardless of race. But readers of her just-released novel, Go Set A Watchman, featuring nearly all the same characters but set, this time, in 1955, when Atticus was 72 and Jean Louise, or Scout, was 26 will find Atticus a determined opponent of integration and a racist who believes Negroes (as he and the rest of polite America then called them) are too inferior to share equally in American society—or even, in many cases, to be allowed to vote. A careful reading of the two books in light of 20th-century southern history, however, shows that the contradiction is far more apparent than real.

Read TIME’s review of Go Set a Watchman here

Atticus’ tragedy, which was more fully revealed in the earlier book, was the tragedy of the white south. Since well before the Civil War, many white southerners—even those who recognized that they exercised a tyranny over black men and women—were too frightened even to think of giving that tyranny up, for fear that their slaves or former slaves would take their revenge and treat their former masters the way they had been treated. Ironically, while Mockingbird appeared just as the civil rights movement was hitting its stride, it is Watchman that explains the enormous resistance that movement faced and how it left an enduring mark on American politics. It may be less inspiring than Mockingbird, but it tells us more about the United States not only in the 1950s, but even today.

In Mockingbird, Atticus directly addresses the race question most clearly after Tom Robinson has been convicted of the rape that obviously never took place. “The one place where a man ought to get a square deal is in a courtroom, be he any color of the rainbow,” he says, “but people have a way of carrying their resentments right into a jury box.” Nothing in Mockingbird suggests that Atticus thinks that Negroes should vote, attend the same schools as white children or even, significantly, have their own attorneys to represent them. He is relatively socially liberal: he seems a bit shocked when he finds that Calpurnia, the black maid who has raised his children since his wife’s death, took them to her own church while he was away, but he stands up for Calpurnia when his sister, Aunt Alexandra, wants him to dismiss her. But while he thinks that white people can and must treat Negroes fairly in the law courts, and while he is willing to put his own life on the line to prevent his client’s lynching before the trial, nothing suggests that his views on the broader race question are out of the ordinary for Alabama in the 1930s.

By 1955, the era in which Watchman is set, a bombshell has been thrown into the South: Brown v. Board of Education, the unanimous 1954 Supreme Court decision mandating integrated schools. Change was coming, and Maycomb wasn’t happy about it. Jean Louise is shocked to find her father taking a leading part in a meeting, in the same courthouse where he won a rape case for a black defendant years earlier, of the local White Citizens’ Council—the more respectable alternative to, but often close ally of, the Ku Klux Klan. And later, in the climactic confrontation between father and daughter, Atticus explains that Alabama’s black population simply cannot be allowed to vote, because there are too many of them and they would elect a black government. He also insists that he and his young law associate Henry take the case of Calpurnia’s grandson, a young black man who has run over and killed a local white drunk in his car. But Atticus doesn’t want this case to try for an acquittal: he simply wants to make sure that the NAACP doesn’t hear about it, send in an out-of-state lawyer, and turn it into a cause.

Evidence suggests that it was the white South’s terror over the coming of the Civil Rights Movement that revived the spirit of the Civil War in the 1950s, and led the South Carolina legislature to start flying the Confederate flag over the state capital in 1962. The terror of federal intervention on behalf of African Americans was sufficient to wipe out a whole species of southern politician, the New Dealer who was liberal on everything but race. The federal government under Lyndon Johnson did desegregate public accommodations and assure black voting rights, but in response, the white South became—and in the deep South, remains—solidly Republican. And horrible though it is, the old spirit was strong enough to inspire the killing of nine black people in a Charleston church, for which Dylann Roof will be tried next year. He is reported to have said, “you rape our women and are taking over our country.” That spirit was not strong enough, however, to keep the Confederate flag flying, and that is a real sign of progress.

Just a few years before a New York editor rejected Go Set A Watchman, William Faulkner, from the neighboring state of Mississippi, published Intruder in the Dust, another tale of a black man unjustly accused of murder who is saved by a couple of courageous whites who discover the real killer. Musing about the situation in the context of mid-century America, Faulkner later estimated that out of 1,000 random “Southerners”—by which he meant white southerners—there might be only one who would actually commit lynching, and but all of them would unite against any outsiders trying to stop one. That, sadly, was not far from an accurate prediction of the white South’s response to the civil rights movement—a response that has reshaped American politics ever since. That is what young Harper Lee documented in Watchman. While she and her editors did the nation and the world a great service by publishing Mockingbird instead, the earlier manuscript gave a much better sense of what the country was up against in the late 1950s—and how we got to where we are today. Now that South Carolina State Senator Paul Thurmond, son of staunch segregationist J. Strom Thurmond, has announced that the Confederate flag does not represent a heritage he is proud of, it seems that Atticus Finch, too, would have no trouble changing his mind with the times.

Historians explain how the past informs the present

David Kaiser, a historian, has taught at Harvard, Carnegie Mellon, Williams College, and the Naval War College. He is the author of seven books, including, most recently, No End Save Victory: How FDR Led the Nation into War. He lives in Watertown, Mass.

More Must-Reads from TIME

- Why Trump’s Message Worked on Latino Men

- What Trump’s Win Could Mean for Housing

- The 100 Must-Read Books of 2024

- Sleep Doctors Share the 1 Tip That’s Changed Their Lives

- Column: Let’s Bring Back Romance

- What It’s Like to Have Long COVID As a Kid

- FX’s Say Nothing Is the Must-Watch Political Thriller of 2024

- Merle Bombardieri Is Helping People Make the Baby Decision

Contact us at letters@time.com