We’re in the meat of hot dog season, the sweet sweaty weeks from Memorial Day to Labor Day, when Americans consume consume 7 billion wieners. That is 21 per person, according to the National Hot Dog and Sausage Council. Sure, we all know that hot-dog ingredients aren’t always the choicest. But there are those very rare occasions, as with almost any food produced in such massive numbers, when something appears inside the bun that even the most zealous hot-dog lover could never find palatable. A TIME request to the USDA’s Food Safety and Inspection Service (yes, the Freedom of Information Act covers encased meats) showed that 38 consumers have reported finding foreign objects in their hot dogs and contacted the feds to complain.

That’s a very small number—think of the billions of hot dogs that peaceably find their way onto our grills —but together the reports provide a window into how America’s sausage gets made. In their wieners Americans reported finding, among other things: “a large ant,” “a peppercorn like material…that appeared to be metal shavings,” “a clump of hair (looks like eyelashes),” “a needle resembling an injection needle,” “a sheared off portion of a metal box cutter,” “a dime,” “a white hex nut” and “a pill.”

“I put a hot dog in the microwave for my toddler and while warming it started sparking and smoking which I thought was weird,” a complaint for 2014 reads, “but took it out and looked at it and didn’t see anything wrong so went ahead and gave it to him. After eating it he kept picking at his teeth and when I looked he had a piece of metal stuck between his teeth.”

“Caller found a large silverfish inside package of hot dogs,” a food safety official noted in a 2015 report. “…Caller owns a food manufacturing business and is therefore familiar with processing and packaging and is concerned that if a large silverfish could be packaged with the hotdogs the plant must have an infestation.”

Janet Riley, the president of the National Hot Dog and Sausage Council and self-dubbed “Queen of Wien,” says, “We sure do what we can to avoid any kind of foreign object in there, and the records suggest that we do a really good job considering the numbers we produce. What’s on the label is what you’re going to find in the product.” Among USDA product recalls, hot dog recalls are relatively rare, and inspectors watch plants closely.

Hot dog integrity appears to have improved since 1999, when the Wall Street Journal reported on what had been, by its estimation, “the wiener’s worst year ever.” Mass-market hot dogs were recalled in spades and blamed by the Centers for Disease Control for listeria poisoning. The Journal reported that Sara Lee, the manufacturer of the popular Ball Park Franks brand, had five foreign-object complaints against it from the start of 1997 until mid-1999. Flash forward and American consumers have filed just one foreign-object complaint concerning Ball Park Franks from the start of 2013 through Feb. 2015.

Still, according to the federal records, 38 Americans claim not to have been so fortunate. “A piece of rubber band (blue),” “what looks like insect larva,” “tiny hard white pieces of plastic about 2-3 mm long,” “a clump of hair or something ratlike,” “the tip of a razor blade,” “sharp metal,” “glass shards,” “a long piece of blue plastic, like very thick plastic wrap,” “a piece of bone, hard, jagged,” “a 3 in. long piece of something, “a metal wire,” “glass and potential mercury,” “a crown,” “a metal staple,” “a metal shard,” “a large piece of bone,” “plastic,” “piece of rubber,” “huge chip of bone,” “huge amount of shredded plastic,” “a metal object… seemed like it was sharpened,” “piece of bone measuring 1 in. by 3/4 of an inch,” “piece of metal… the size of 2 or 3 grains of sand,” “metal button shaped like a sharp object,” “a bug,” “a sharp hard object,” “two hairs… one was short, black and could have been facial hair. The second hair was thinner and was actually sticking out of the hot dog.” Reported one caller: “The hot dog appeared to be written on with a black magic marker with the letter ‘T’.”

Most hot dogs are made of the same beef or pork or poultry one would buy elsewhere in the supermarket meat aisle. Well, OK, that familiar meat, but spiced and blended with ice chips into a batter and then stuffed into casings and cooked and then peeled and often packed in plastic with sodium nitrate or sodium nitrite as a preservative. Also occasionally with fat, water, dry milk, cereal or isolated soy protein added, all of it permissible under U.S. Department of Agriculture regulations. So at least 54.5 percent of the hot dog must be meat. And those are the ones that pass USDA mustard. Er, muster.

A national pastime

While now as American as baseball, apple pie and Chevrolet, the hot dog is in fact a foreign object. In Germany, they have been slinging sausage since at least the fourteenth century, many centuries before Polish immigrant Nathan Handwerker set up his eventually famous nickel hot dog stand on Coney Island in 1916. (On Friday, Famous Nathan, a documentary of Handwerker’s life created by his grandson Lloyd Handwerker, was released in movie theaters.) The German immigrants who landed in America in the middle of the nineteenth century brought their sausages with them, says Bruce Kraig, hot-dog historian and the author of Man Bites Dog: Hot Dog Culture in America. And a still-young nation that liked its food cheap, hot, fast and meaty went about making the sausage its own. Chicagoans cast their lot with mustard, onions, relish and a host of other toppings. Michiganders went with the chili-and-onion covered Coney Dog. New Yorkers more often served them with merely mustard.

The hot dog was also, Kraig says, the first-ever American food with a real relationship to leisure. They were the food of Coney Island, of Chicago’s Riverview Park, of the Jersey Shore—and of baseball, the new national pastime.

Americans loved their hot dogs. But they rarely bothered to sweat what might be in them. The name “hot dog” came from a running joke among Yale students in the 1890s that the sausages they loved so much might contain dog meat among the tasty butchers’ scraps. “That’s American humor for you. Mordant and wry,” Kraig says.

But the supermarket hot dogs we know now have little in common with the local, butcher-made hot dogs of the late nineteenth century. It would take the development of major meatpacking factories in Chicago and of new preservation and refrigeration technologies to clear the way for the mass-produced hot dog. (One such Windy City factory, the Armour Meat Packing Plant, worked like this, Kraig says: Cows would enter on the top floor for slaughter. Then their carcasses would make their way through the factory, and workers would carve off special cuts as directed. By the time the carcasses reached the bottom of the building, the beefy oddities that remained were fit for hot dogs.) The mass-produced hot dog arrived hand-in-hand with the magic of advertising. Chicago, after all, built not only America’s meatpacking plants but the Oscar Mayer Wienermobile in 1936.

Indeed, the story of the hot dog contains the stories of so many things we as Americans hold dear—of recreation (of baseball!), of industry, of intense regional difference, of transcendent marketing, of cheerful insouciance in the face of troubling whispers. So if you should find yourself nearby a friend’s grill before summer’s end, with a hot dog in your hand, know that, as you prepare to bite into it, as you sniff its barely peppery aroma, you will soon be sinking your teeth into this beautiful and brilliant nation itself. And maybe a razor blade too. Hopefully not. Eat up!

Jacob Koffler contributed reporting to this story.

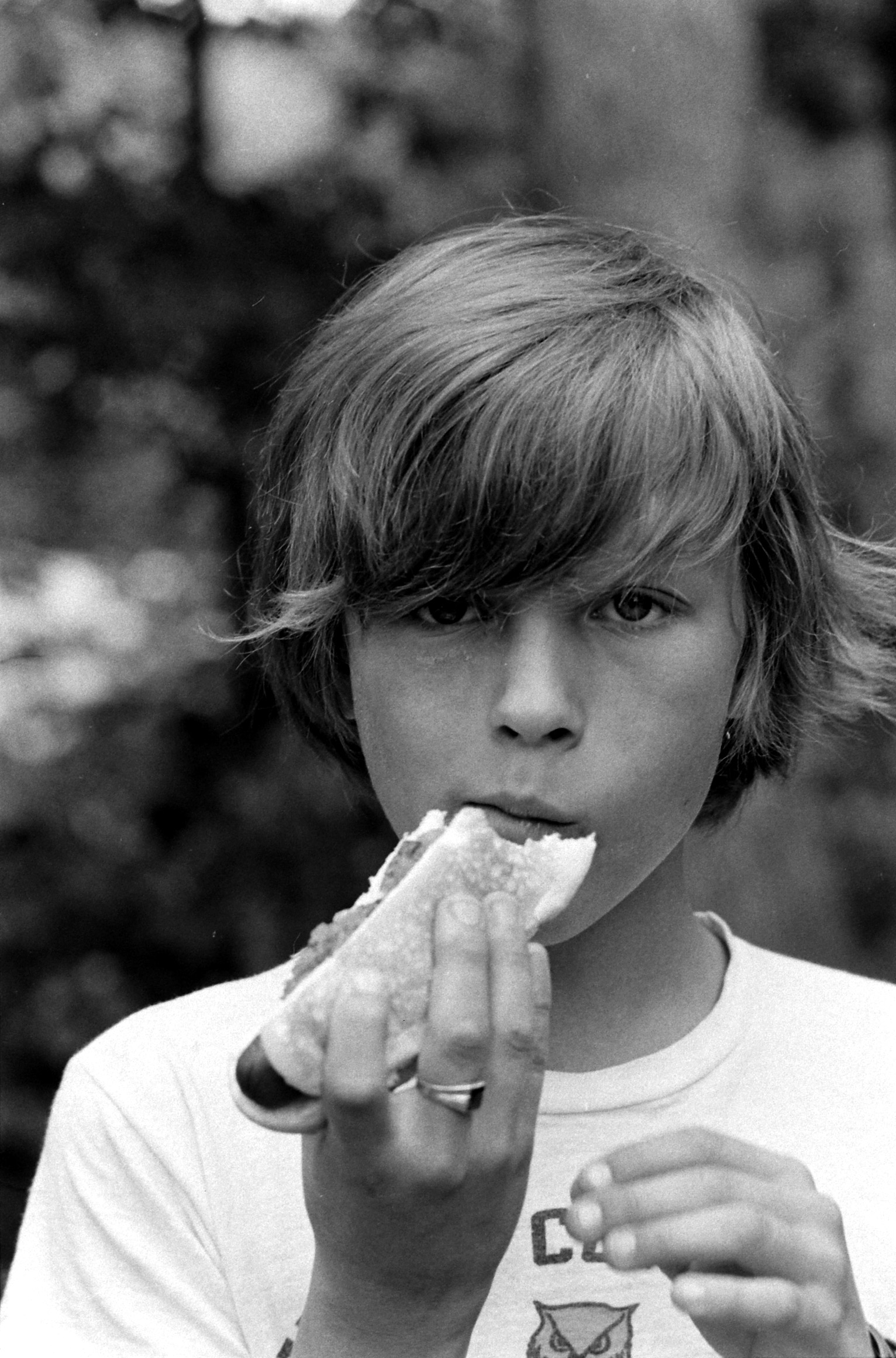

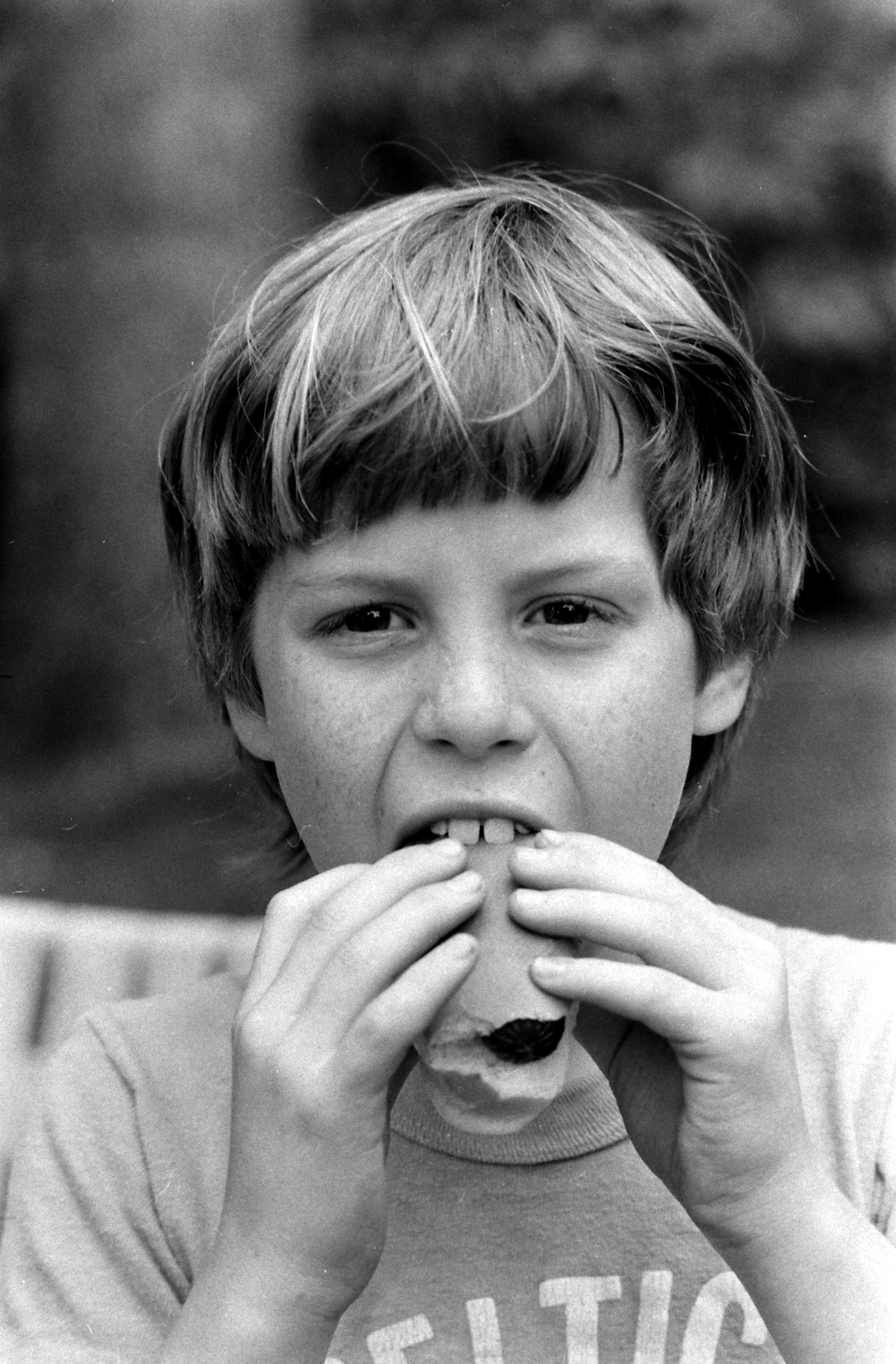

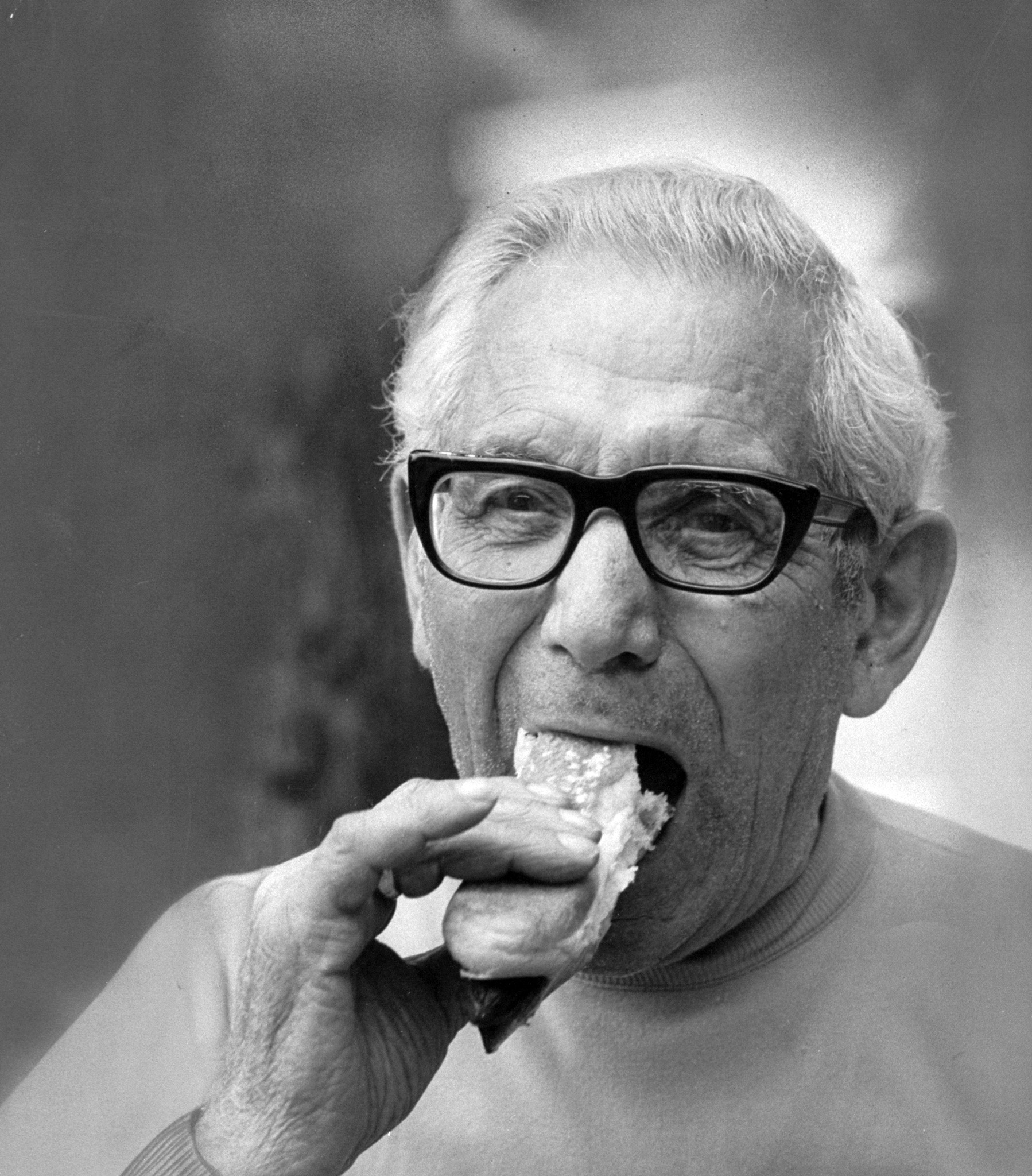

See the Best Vintage Photos of People Stuffing Their Faces With Hot Dogs

More Must-Reads from TIME

- Donald Trump Is TIME's 2024 Person of the Year

- Why We Chose Trump as Person of the Year

- Is Intermittent Fasting Good or Bad for You?

- The 100 Must-Read Books of 2024

- The 20 Best Christmas TV Episodes

- Column: If Optimism Feels Ridiculous Now, Try Hope

- The Future of Climate Action Is Trade Policy

- Merle Bombardieri Is Helping People Make the Baby Decision

Write to Jack Dickey at jack.dickey@time.com