This week at least, let’s call Pluto a planet. You’d better get used to it, because given the kind of love the little world is getting, it’s an honorific that might be sticking around.

Pluto was always a cosmic screwball, a ball of rock and ice smaller than our moon that tumbled out of the Kuiper Belt, fell in with a group of eight legitimate planets well above its station, and hung around along enough that it became, de facto, one of the gang. That was never a sure thing. While the planets from close-in Mercury to distant Neptune orbit in the flat, more or less around the sun’s equator, Pluto dive bombs the solar system at an inclination of 17 degrees, plunging below and above the equatorial plane. Its orbit is an ellipse, with a maximum distance of 4.59 billion miles (7.38 billion km) from the sun and a minimum of 2.76 billion miles (4.44 billion km), while the other planets orbit in more or less a circle.

Until 2006, Pluto was called a planet, before sticklers at the International Astronomical Union, who decide such things, busted it down to a dwarf planet, for a whole lot of reasons that made perfect sense astronomically but none at all sentimentally. But never mind now, because Pluto, the runt of the solar system litter, is currently everybody’s favorite.

The reason, of course, is the New Horizons probe, which after a nine-year, 3 billion-mile (4.8 billion km) journey, just passed within 7,750 miles (12,472 km) of Pluto’s frozen surface, snapping pictures and taking readings all the way. The images and the data took 4.5 hours to reach Earth even moving at light speed, and most of the time the ship has been in space it has simply been storing what it’s learned in on-board computers. The data dump that finally began when the probe passes Pluto will take up to 16 months to complete.

But the pictures come first and the best that have been returned so far showed a brown and tan world with a range of curious features, including four Missouri-sized dark spots along its equator. In the southern hemisphere is a vast, pale region shaped exactly like, yes, a heart, because while science doesn’t always go all serendipitous on you, when it does, it makes the most of the moment.

In some ways, however, the bigger deal is that New Horizons is where it is at all. The probe, which is one of the smallest ever built—about the size of a grand piano—and easily the fastest, at 31,000 mph (49,900 k/h), arrived at its closest approach to Pluto just one minute later than was forecast by the trajectory planners when it was launched. And it nicely hit the 36 by 57 mile (60 by 90 km) window it was aiming for—the equivalent of a commercial airliner landing within a tennis ball’s width of its target, as NASA likes to boast.

Today especially, boasting is something NASA is entitled to do. New Horizons completes a half-century reconnaissance of all nine planets in our solar system, with some—Uranus and Neptune—getting just one visit each, while others got many. Mars is currently so well-populated by probes that it has something close to a mini-infrastructure. And not to put too fine or jingoistic a point on it, but the overwhelming majority of spacecraft ranging anywhere in the solar system carry the NASA decal and the American flag.

That matters. It will be a while—many generations—before human beings truly become a multi-planet species. And the world we’re likeliest to stake our first claim to, Mars, is a forbidding place that at best will serve as a cosmic equivalent of the McMurdo Station in Antarctica—a research base that is far more a work station than a home.

But humanity—led by the U.S.—has made a start, sending our buoys throughout the solar system where they bob and drift and teach us things we never could have known if we didn’t have the smarts and the will to spend the money and build the machines. The points the species puts on the board when one of these improbable ships gets where it’s supposed to go and does what it’s supposed to do are the hardest-won of all. Our opponent in these cases isn’t another nation-state with which we’re competing for land or influence or wealth, it’s the laws of physics themselves.

Difficult as our terrestrial challenges seem, they are all parts of a system we created. There was no such thing as the laws of economics until we emerged from the swamp and created them. Ditto the laws of politics. We are always free to change the rules—and we often do.

The laws of nature have always been here and beating them—climbing out of the gravity well of Earth, keeping a machine like New Horizons powered in the deep freeze and deep black of space—is not the kind of thing that can be settled over a negotiating table in Vienna or Geneva. Physics won’t compromise; it won’t relent on one of its points if you relent on one of yours. Playing its game by its rules is the only way to win.

It is both good for the world and a bit sad for science that on the very morning New Horizons made its rendezvous with Pluto, the biggest headlines are going to the much-awaited international nuclear deal with Iran. Peace is undeniably a good thing, but it’s something we can make happen any old time if we simply choose to. Interplanetary travel is something else.

Surely, it is just coincidence that among the many Tweets sent out by Iranian President Hassan Rouhani about the nuclear deal is one that reads, “#IranDeal shows constructive engagement works. With this unnecessary crisis resolved, new horizons emerge with a focus on shared challenges.”

Rouhani’s new horizons, of course, is very different from NASA’s New Horizons. Both are historic; both are extraordinary news. But with due applause for the peacemakers, today belongs to the explorers.

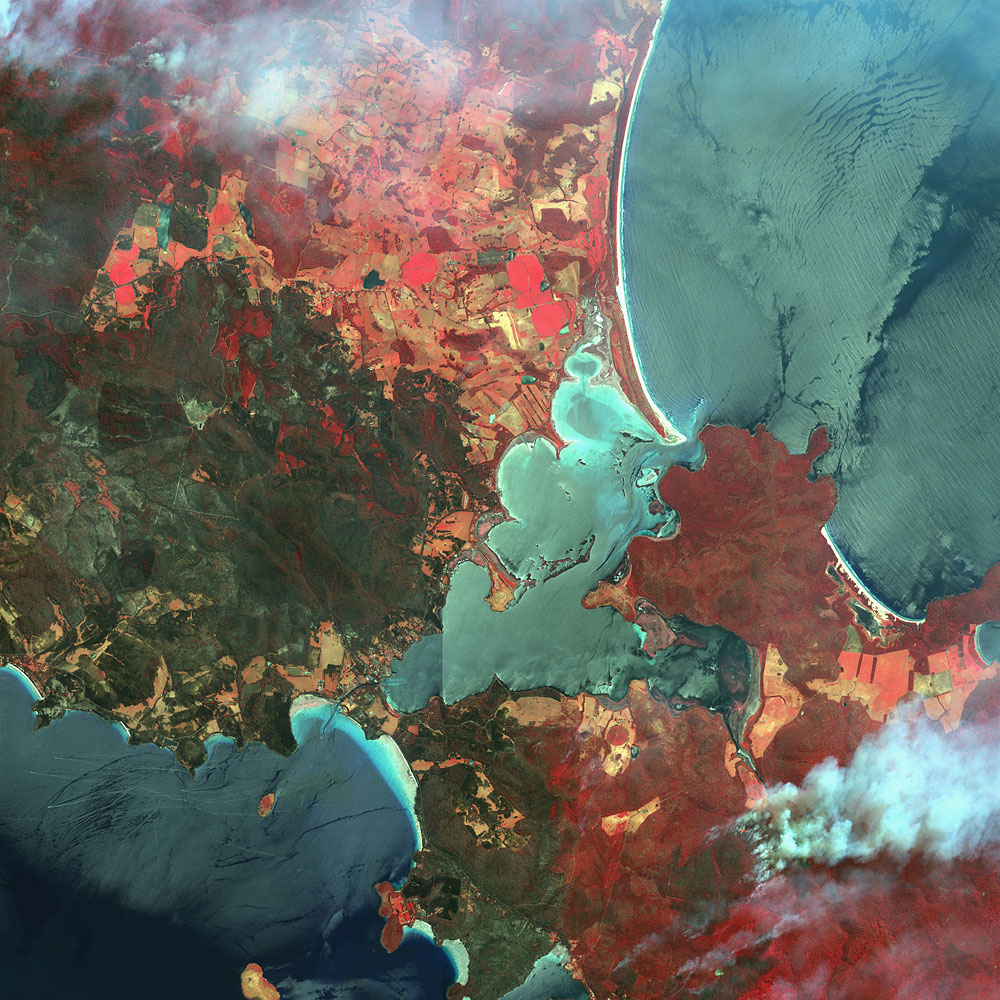

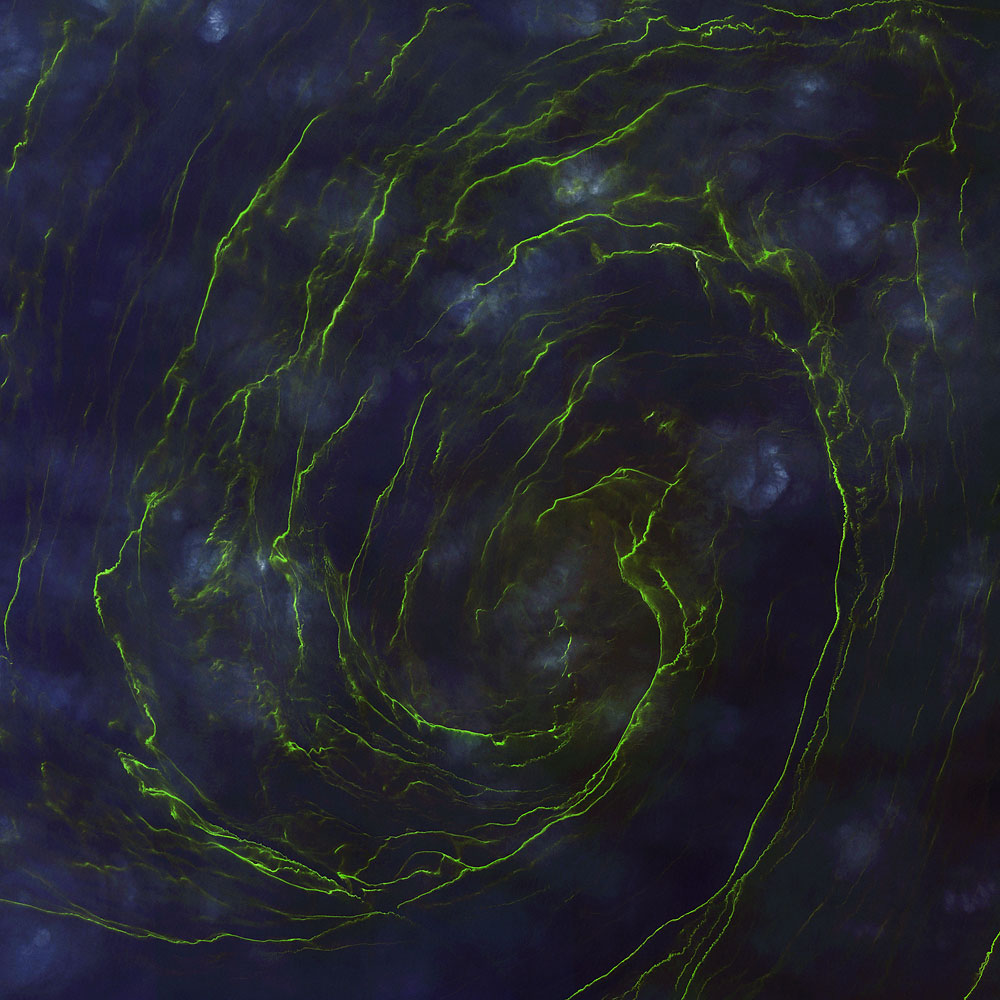

PHOTOS: 20 Breathtaking Images of Earth From Space

![{

bandList =

[

4;

3;

2;

]

} Colorado River](https://api.time.com/wp-content/uploads/2014/03/colorado.jpg?quality=75&w=2400)

Read next: NASA Just Debuted This Amazing Pluto Image on Instagram

More Must-Reads from TIME

- Cybersecurity Experts Are Sounding the Alarm on DOGE

- Meet the 2025 Women of the Year

- The Harsh Truth About Disability Inclusion

- Why Do More Young Adults Have Cancer?

- Colman Domingo Leads With Radical Love

- How to Get Better at Doing Things Alone

- Michelle Zauner Stares Down the Darkness

Write to Jeffrey Kluger at jeffrey.kluger@time.com