It’s the wages, stupid.

That’s the magic sauce—in just four words—that Hillary Clinton believes will make her the next President of the United States. In a speech Monday to lay out her approach, she chose a more verbose version of the same message. “Wages need to rise to keep up with costs. Paychecks need to grow. Families who work hard and do their part deserve to get ahead and stay ahead,” she said. “The defining economic challenge of our time clear. We must raise incomes for hardworking Americans.”

As a theme, the approach is not new. A chart showing the divergence between median income growth and productivity growth over the last decade sat at the heart of Barack Obama’s 2012 campaign for President. “‘I’m working harder and falling behind,'” David Simas, Obama’s political strategist, explained after the 2012 election. “That was the North Star. Everything we did and everything we said was derivative of that sentiment.” As she spoke Monday, Clinton’s campaign tweeted out a version of the same chart that once hung at Obama’s Chicago campaign headquarters and now hangs in Simas’ West Wing office.

The difference now is that Clinton inherits a situation that is even more dire for American voters than the one that Obama struggled with over his past two campaigns, both of which promised improvement for middle class incomes that has yet to arrive. Even as the labor market has tightened in recent years and the national economy has continued to grow, wages have remained flat or, in many cases, declined.

A recent analysis of Census data by Democratic economist Robert J. Shapiro, whose work helped inform the Obama campaign’s approach, found that the economy shifted gears for American incomes after the 2001 recession. “Everybody declines from 2002 on relative to the 1980s and 1990s, and probably a majority of the country saw their incomes decline as they age,” he said, noting that unlike many economic indicators, this is one that voters feel directly. “It’s politically important because it’s people’s actual experience.” Shapiro found that the only two groups who saw their incomes increase on average between 2002 and 2013 were college graduates and households that were in their early 20s at the beginning of the decade.

To counteract this shift, Clinton proposed a variety of policy buckets she plans to focus on, many of which she did not detail. These include tax changes that will encourage large companies to share profits with employees, tax increases for the wealthy and new regulations of the financial sector. “The truth is the current rules for our economy do reward some work, like financial trading, for example much more than other work, like actually building and selling things, the work that has always been the backbone of our economy,” she said. “To get all incomes rising again, we need to strike a better balance.”

The focus on wages also gives a frame for Clinton to roll out a raft of other evergreen liberal policies, which could have indirect impacts on wage growth. These include better family leave policies to encourage more women to enter the workforce, lower health care costs, better early childhood education subsidies, more spending on infrastructure and “enhancing” Social Security.

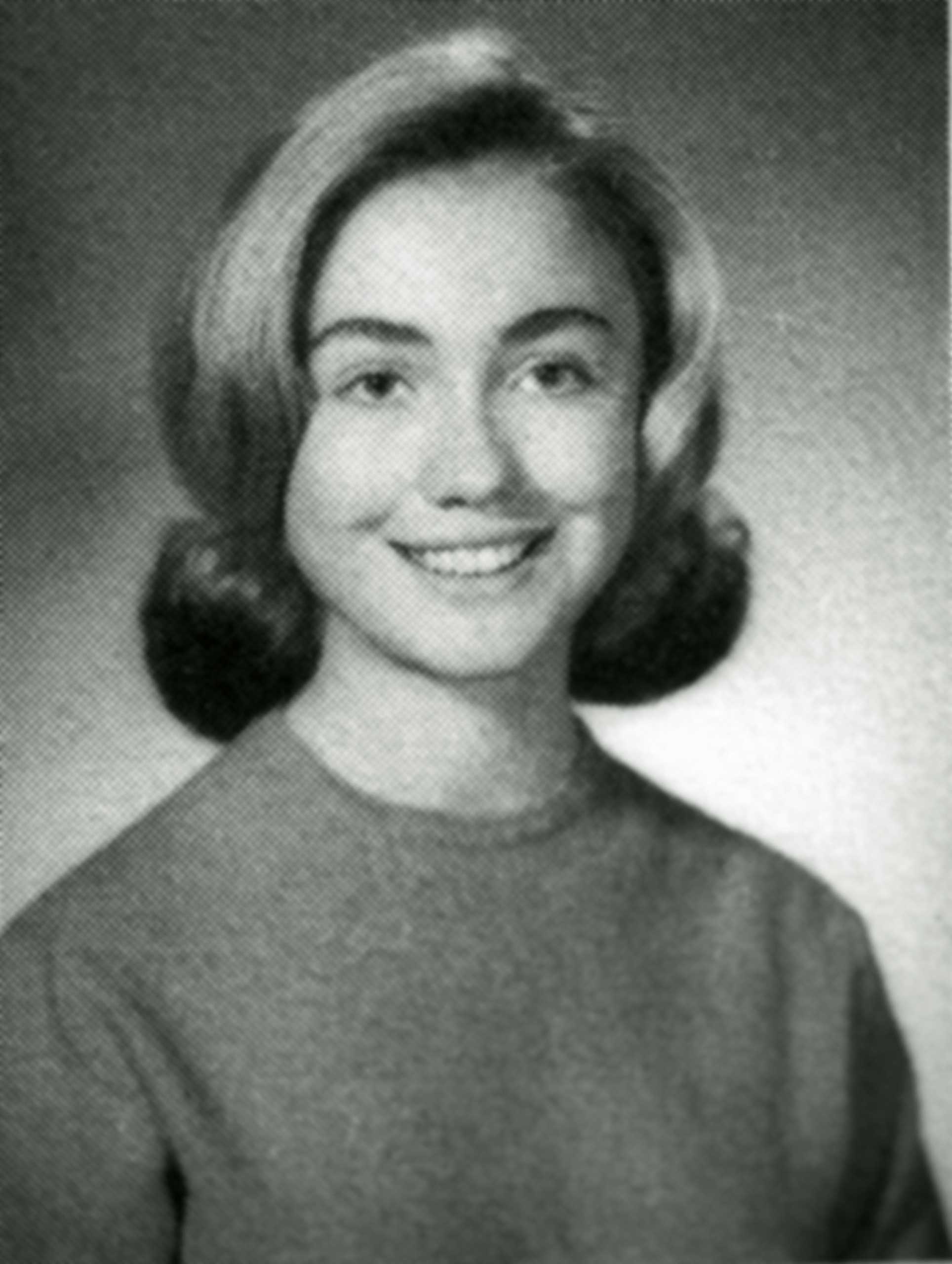

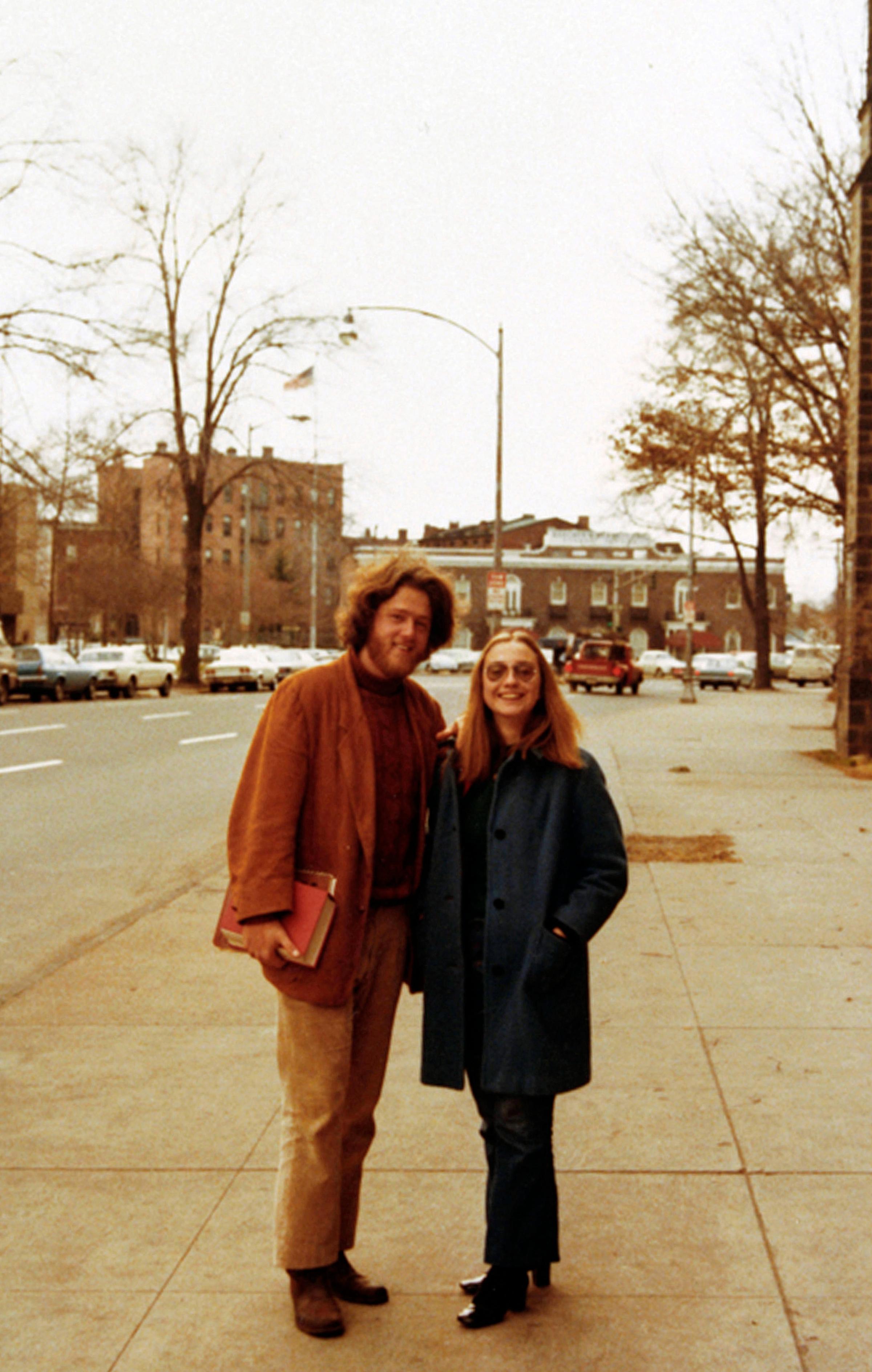

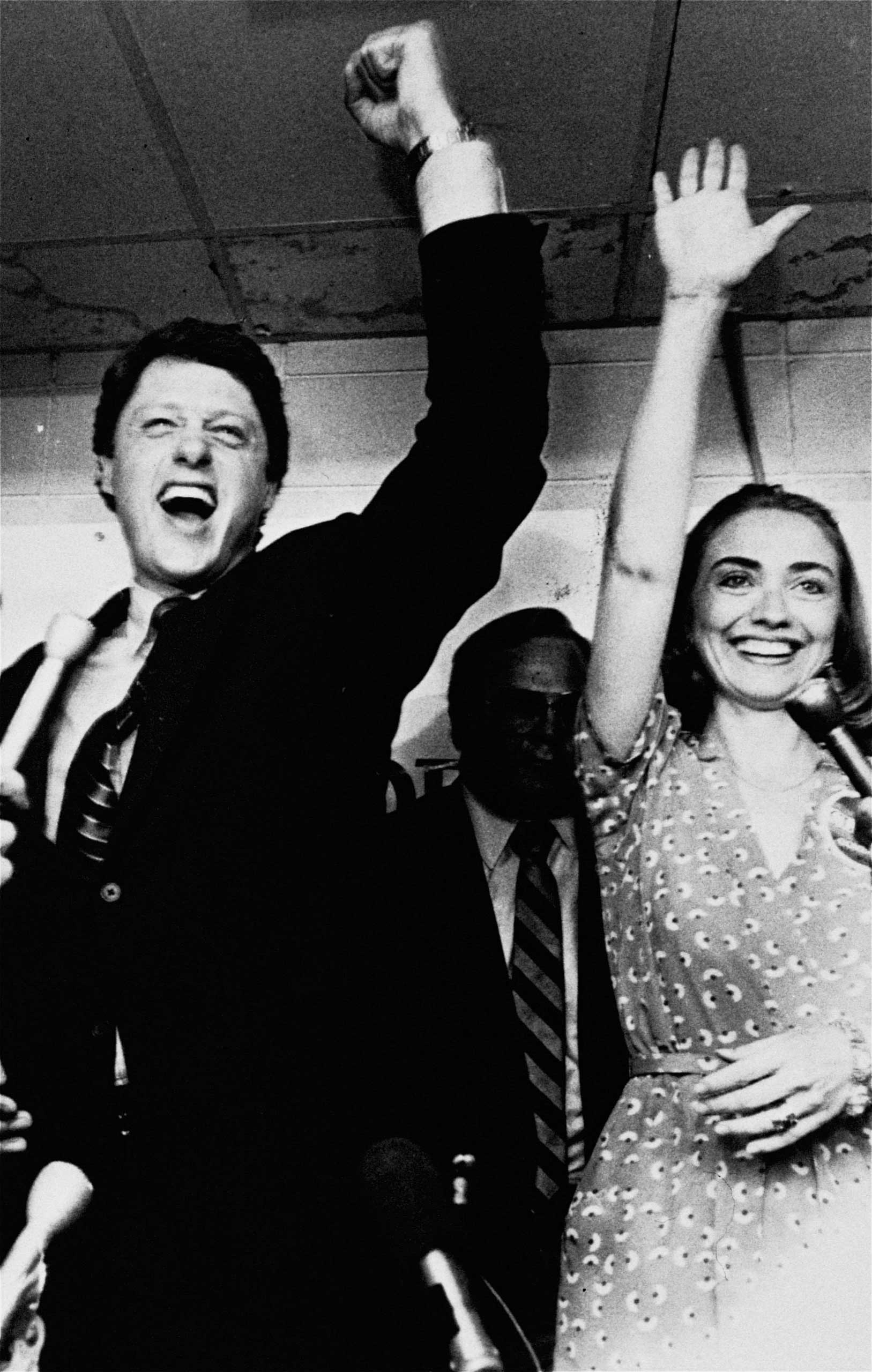

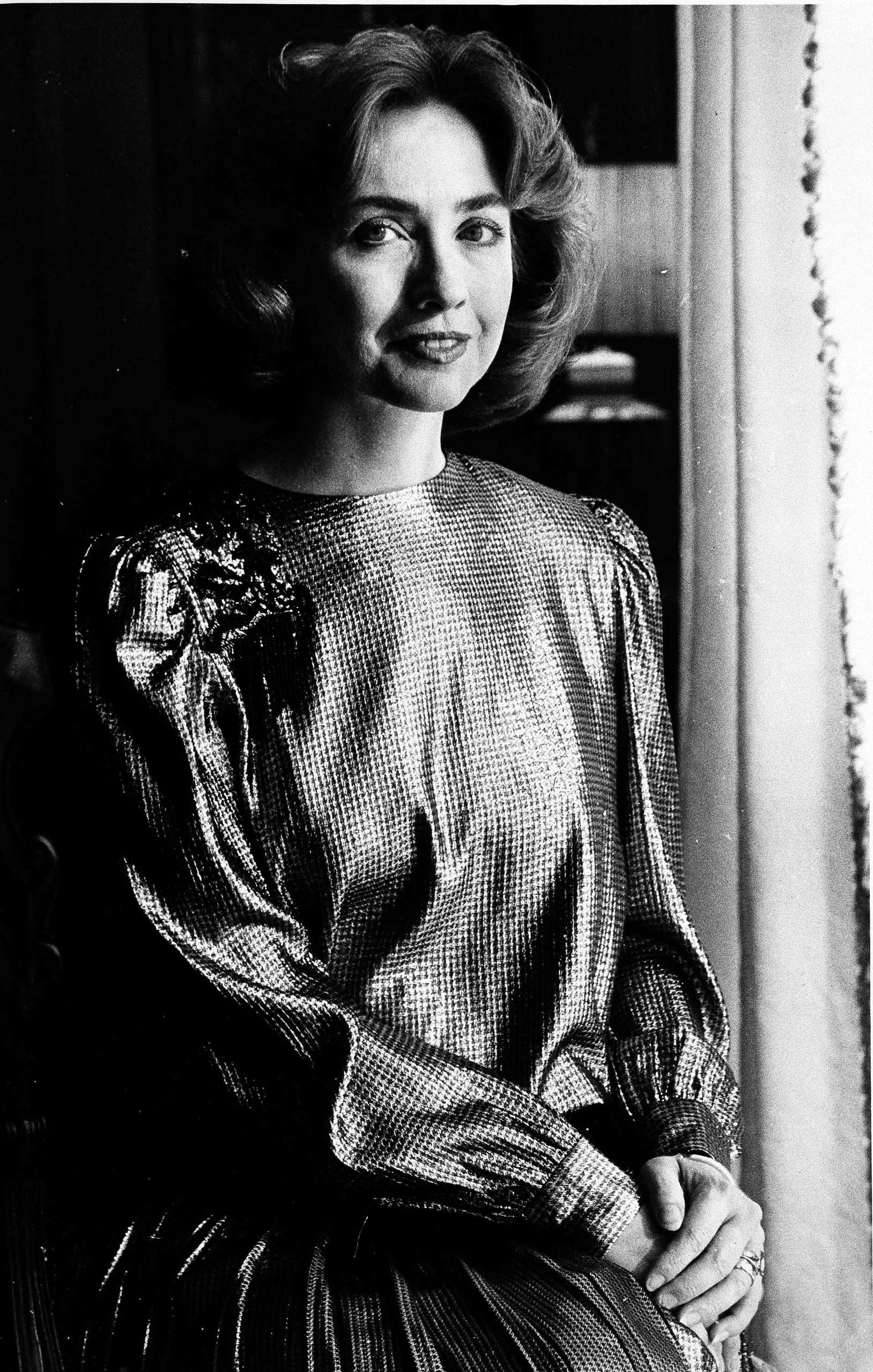

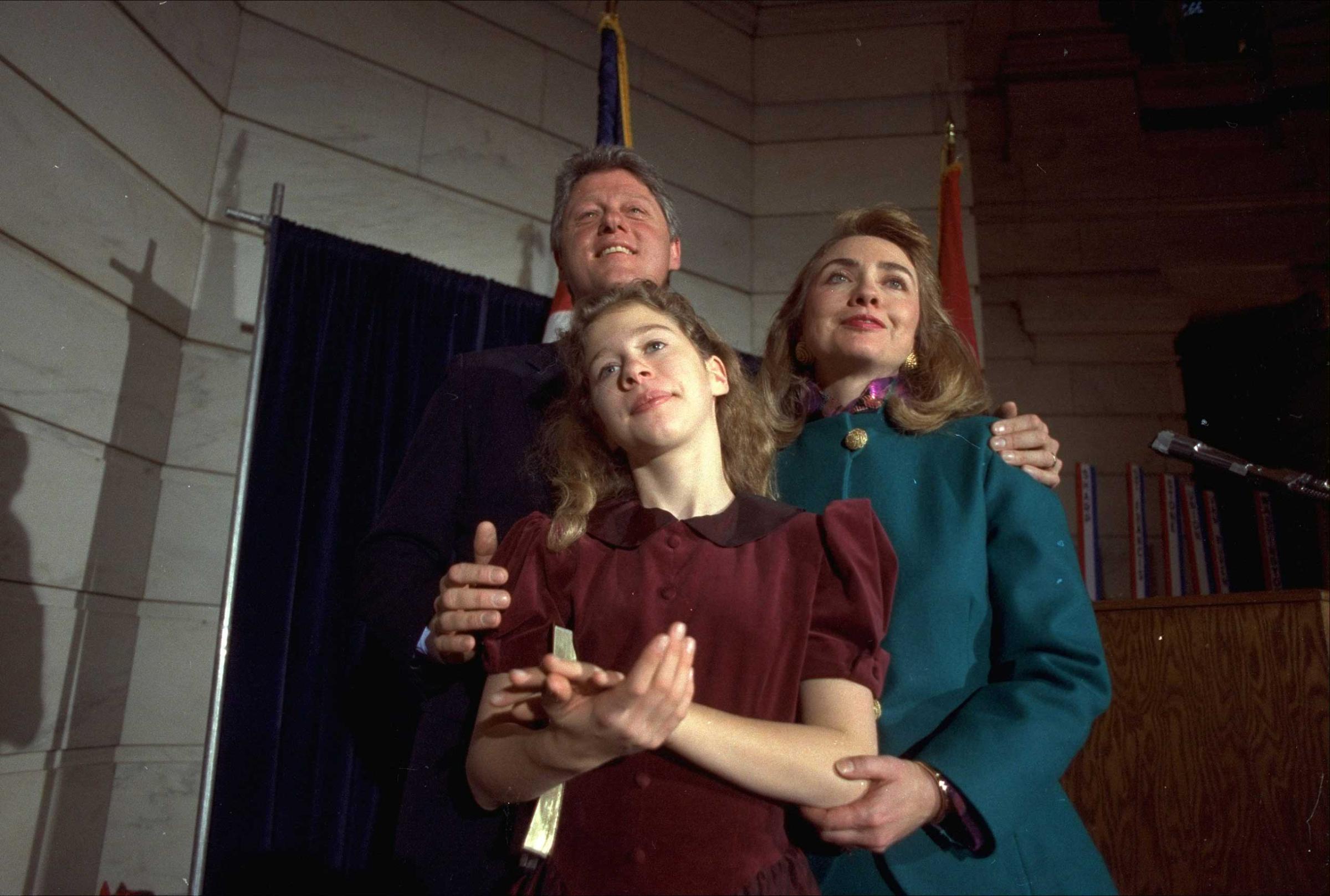

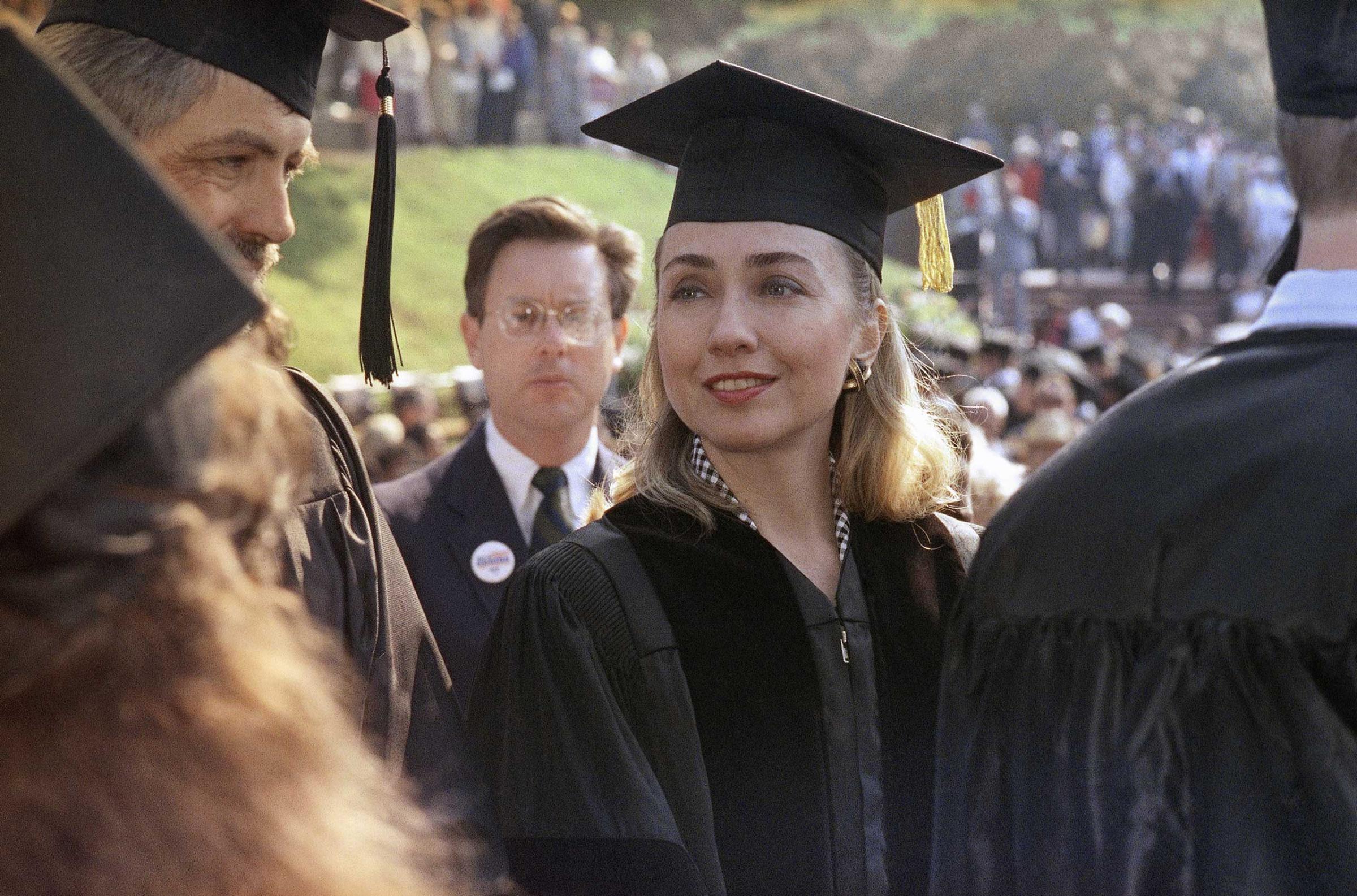

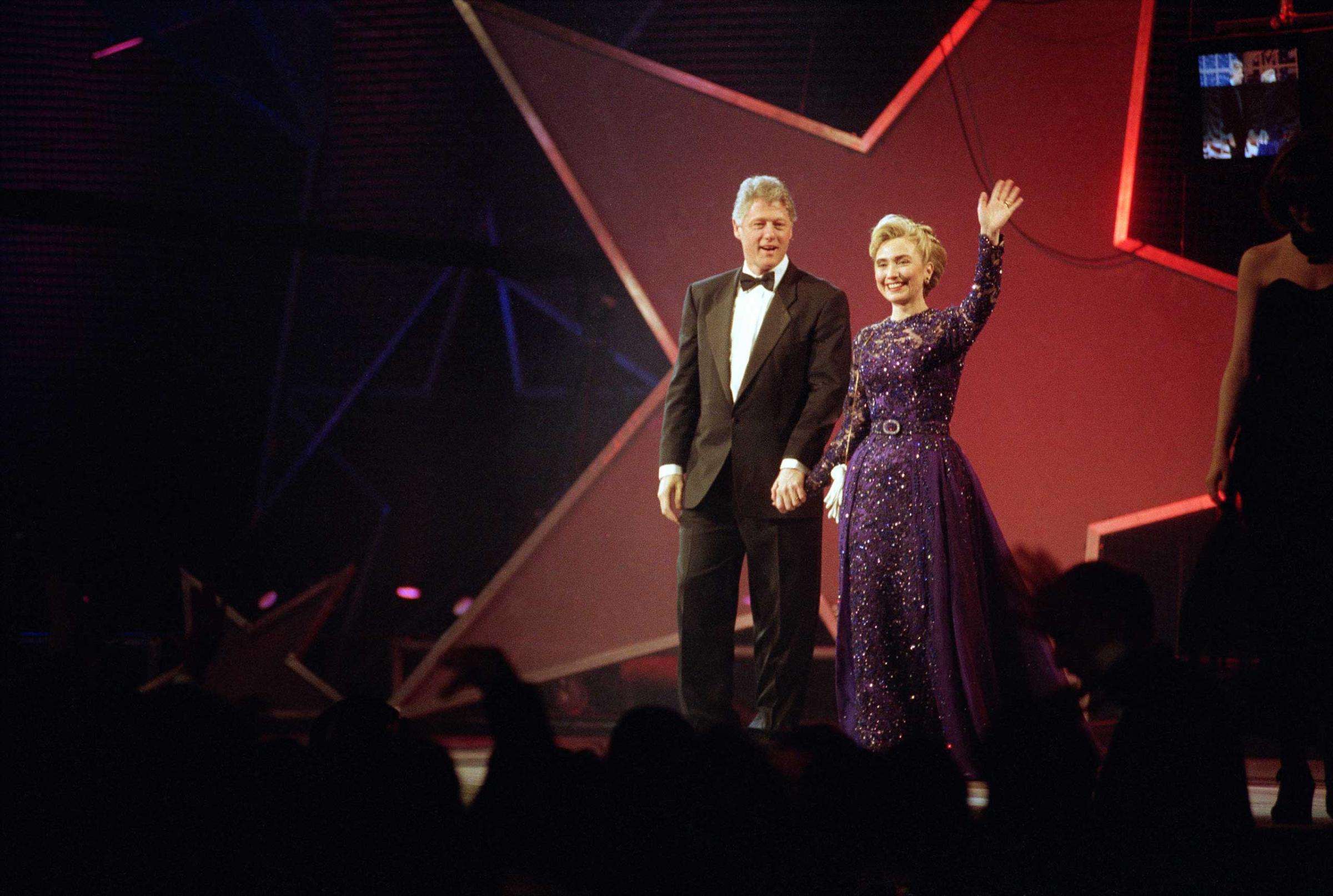

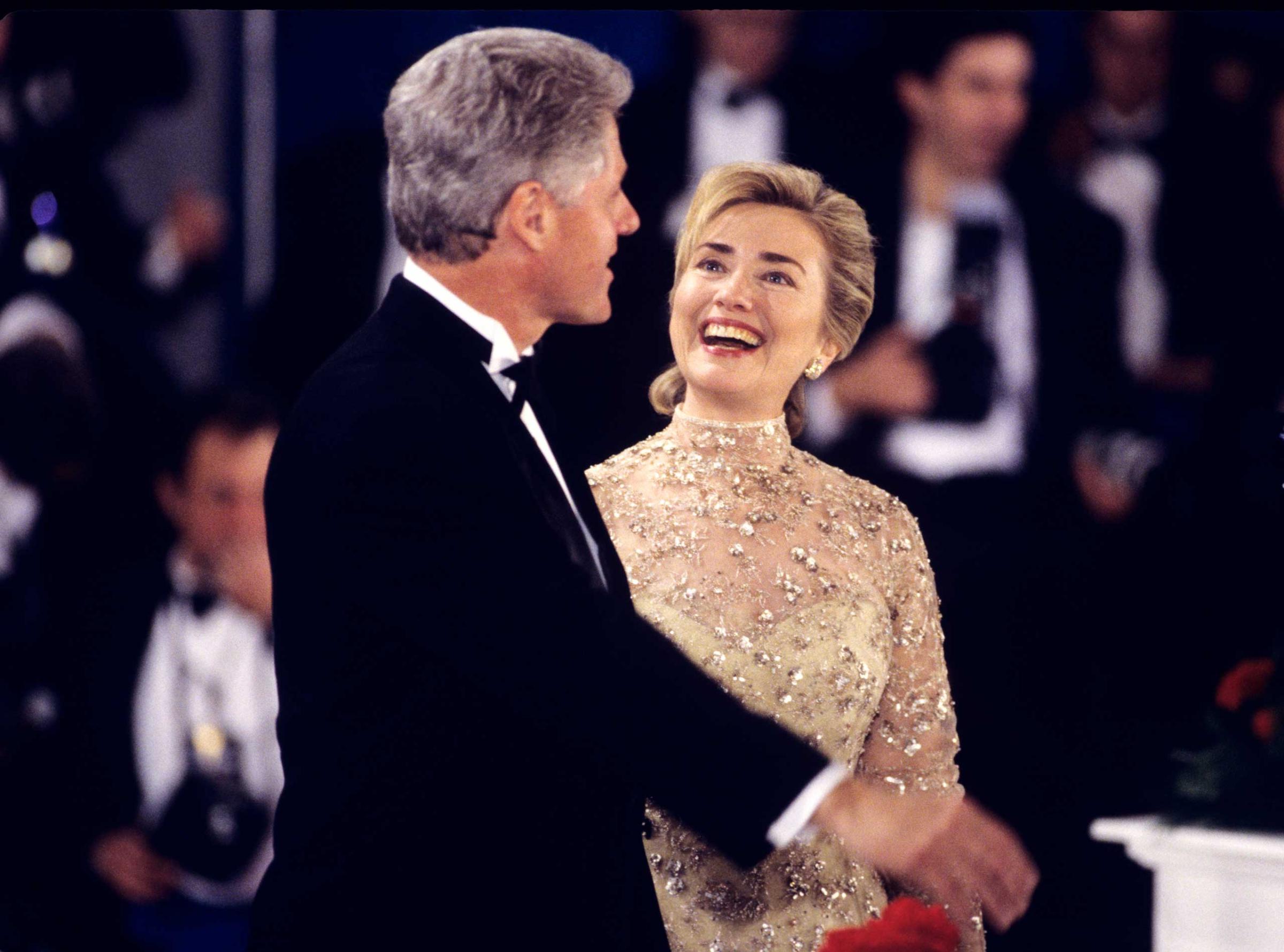

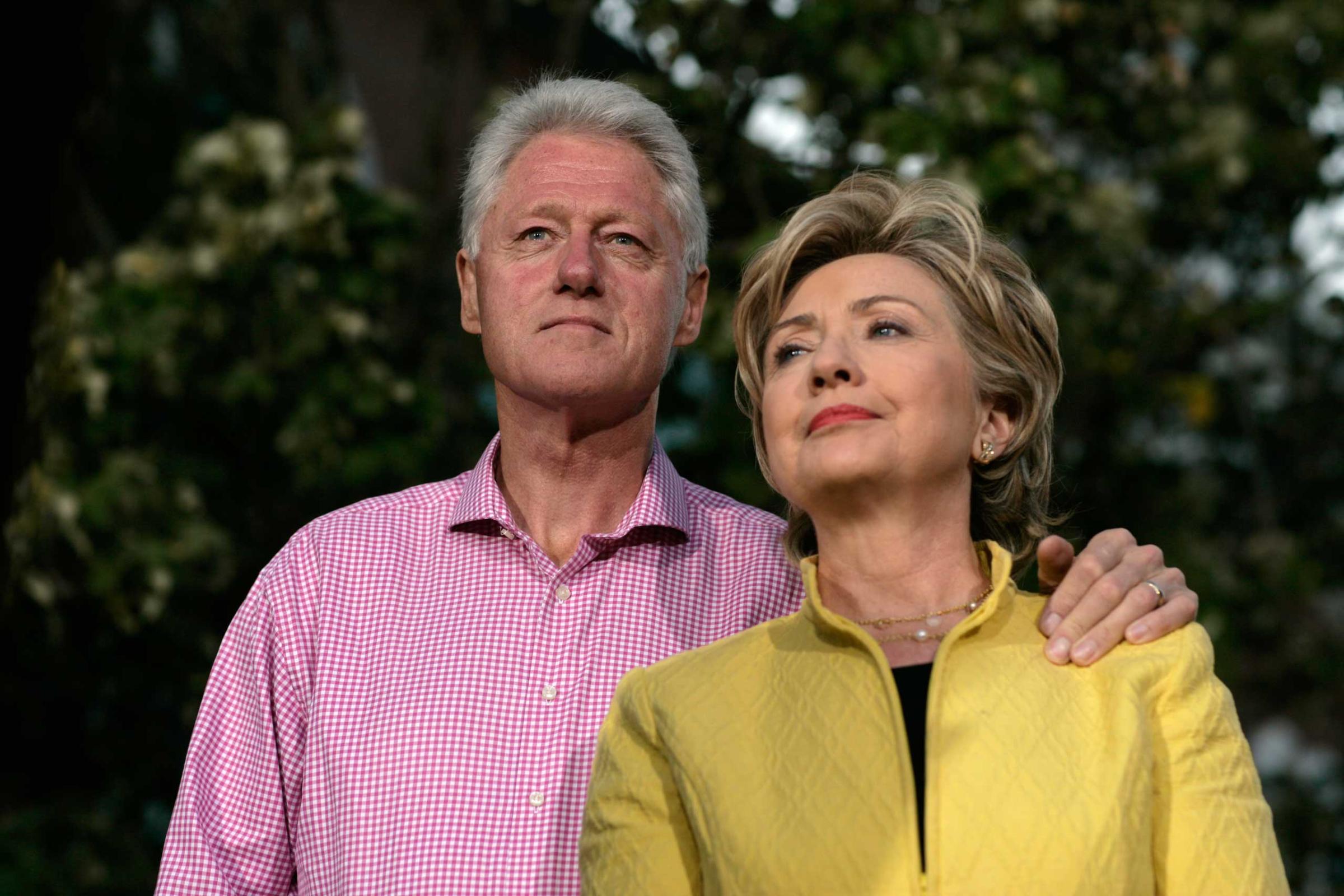

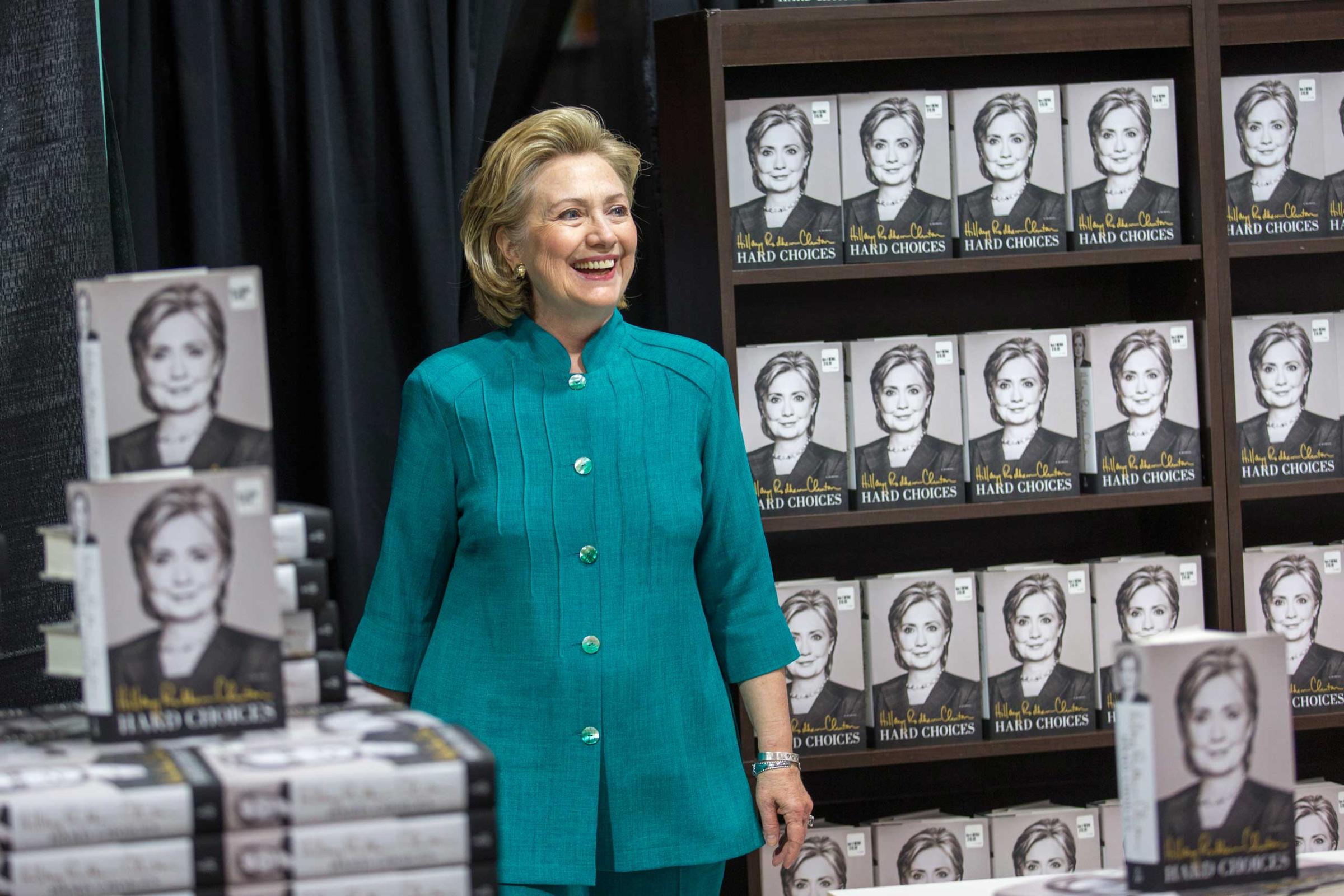

See Hillary Clinton's Evolution in 20 Photos

Overall, the rhetoric draws heavily on the work of the left wing of the Democratic Party, including Massachusetts Sen. Elizabeth Warren, Vermont Sen. Bernie Sanders and former Clinton Administration economist Joseph Stiglitz. Though Clinton stopped short of calling for redistribution of wealth to combat inequality, a constant theme of the left, she did embrace the notion that the current economic stagnation for many Americans is a policy choice. “The choices we make in the years ahead will set the stage for what American life in the middle class and our economy will be like in this century,” she said.

At two points, Clinton contrasted her vision with the Obama Administration. First, she criticized the Justice Department and regulators for not being aggressive enough in prosecuting the misdeeds of financial firms. She also called for more financial regulation. “I will appoint and empower regulators who understand that too big to fail is still too big a problem,” she said, in a swipe at Obama, who has argued that the problem of too-big-to-fail was largely solved by financial reform in 2010.

Perhaps most important, the speech set up a contrast with Republican frontrunner Jeb Bush, who has laid out an economic vision of rising prosperity based on growing the whole economy by 4% annually, a target that few economists think can be reached. Clinton’s argument is that total growth is not enough. There also needs to be a reshuffling of the rules that makes the gains from that growth more widely distributed.

The question for Clinton is much the same as the challenge faced by Obama. She may have diagnosed the disease in a way that the American people have endorsed in the past, but can she deliver the antidote? Republicans, who have a dramatically different world view, have been able to block many of Obama’s reforms, and would likely have similar power under a Hillary Clinton Administration. There is also a skepticism, shared by many liberal economists, about just how much the reforms she laid out will impact incomes, which have been under pressure because technology and global competition have put a cap on prices and an increase in the unemployment rolls.

But that is a question for a later time. The first jobs for Clinton are to win the nomination and then the White House. And by borrowing heavily from her successful predecessor, her team believes she has a winning formula.

More Must-Reads from TIME

- Cybersecurity Experts Are Sounding the Alarm on DOGE

- Meet the 2025 Women of the Year

- The Harsh Truth About Disability Inclusion

- Why Do More Young Adults Have Cancer?

- Colman Domingo Leads With Radical Love

- How to Get Better at Doing Things Alone

- Michelle Zauner Stares Down the Darkness

Contact us at letters@time.com