Pendulums Swing, and when Bill de Blasio was running for mayor of New York City, one was going his way. A civil rights activist, the Democrat campaigned as a critic of the NYPD, finding fault with, among other things, its 1,000-officer counterterrorism division. Vaunted in security circles, the division was better known in some minority communities for an unsettling history of overreaching. Its demographics unit, which de Blasio shut down shortly after taking office in early 2014, sent undercover officers to eavesdrop on conversations in Muslim communities and maintained files on “ancestries of interest.”

Then ISIS appeared–half a world away but with a force that sent the pendulum careening back. Threat levels have gone up around the globe. And in America’s largest city, a theoretical debate about the role of political leadership in combatting terrorism has assumed a sudden gravity, as experts ask whether under de Blasio New York City is still equipped to stop an attack that seems ever more possible.

It’s not an entirely local matter. A similar debate is playing out in Washington, where the Patriot Act was allowed to expire in May. It was replaced with a less swaggering successor that put new restrictions on the National Security Agency. But it’s different in New York City, and not only because responsibility for an attack–perhaps the lone-wolf brand analysts say may be impossible to prevent–will not be diffused among 535 voting members. One-third of Gotham’s residents were born in another country. And the city’s marquee status as a target is undimmed. While the number of plots uncovered by the NSA’s bulk data collection totaled zero, since 9/11 the NYPD counts 24 plots it has been involved in stopping.

“New York’s a special case. I view the NYPD to be the second best intelligence organization in the country–and I’m a former director of the CIA,” says Michael Hayden, who also ran the NSA. Now a security consultant at Chertoff Group, Hayden emphasizes that his glowing opinion of the NYPD was formed under de Blasio’s predecessor, the independent Michael Bloomberg, and Bloomberg’s police commissioner, Ray Kelly. “I thought a regime that was harshly criticized at the end of the Bloomberg-Kelly era had made New York measurably safer,” Hayden tells TIME. “If the Tsarnaev brothers were trying to do the New York Marathon, they wouldn’t have gotten away with it, because the behavior that was exhibited in the mosques–the NYPD system would have picked it up, and they would have been in their net.”

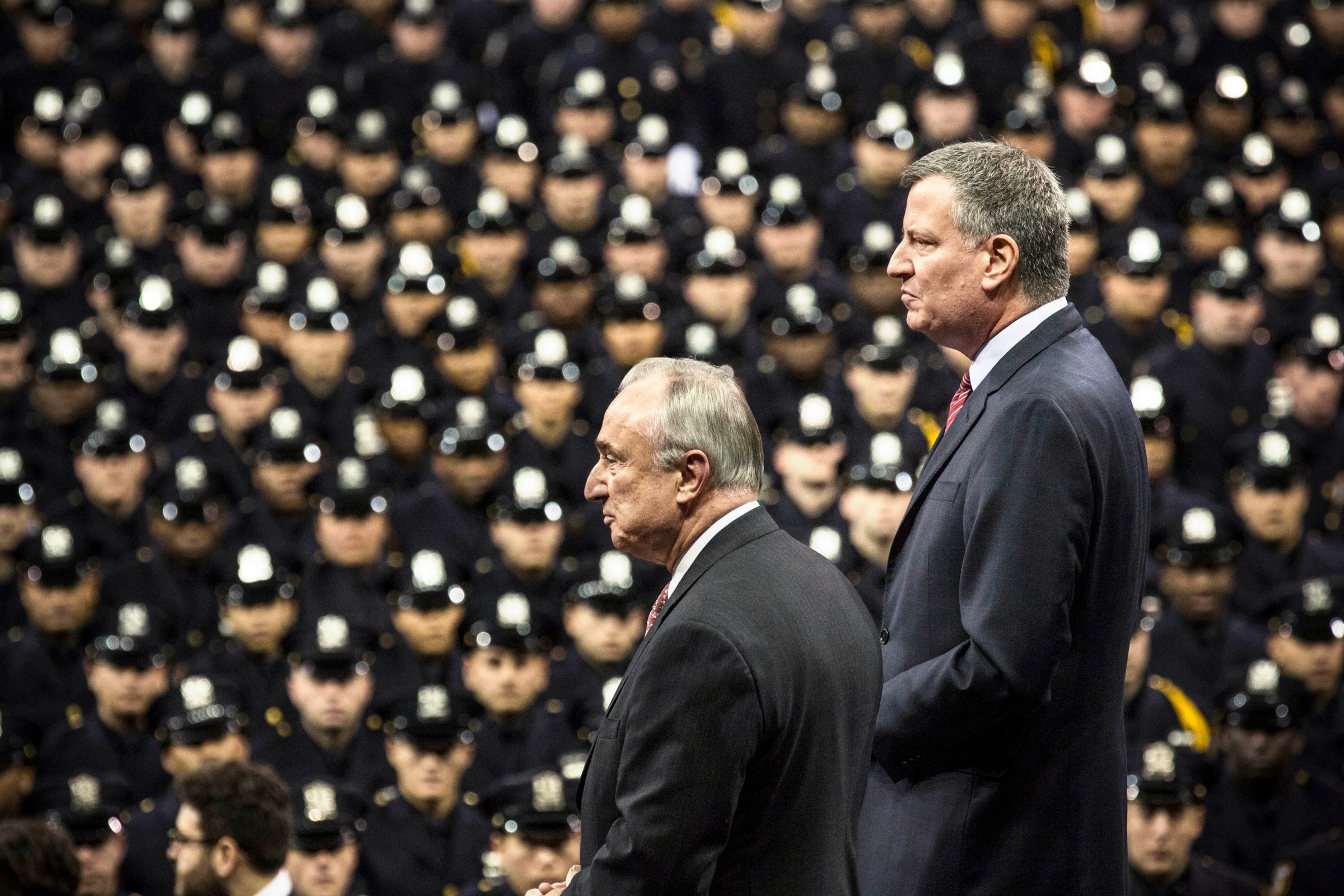

The question circulating in security circles in recent months has been: Is that still true under de Blasio? The verdict appears to be yes, but it can be hard to make out amid the new administration’s efforts to smooth the counterterrorism operation’s hard edges. For example, among the NYPD programs the new mayor ended was “mosque crawlers,” the inartful name for dispatching informants to houses of worship to watch for radicals. Stopping the use of “crawlers” and “rakers” was a move that, like the very public shuttering of the demographics unit, sent one signal to civil libertarians and another to security mavens. And some hawks were concerned that de Blasio’s police commissioner, William Bratton, altered the organizational chart, blending into a single unit two bureaus, intelligence and counterterrorism, each of which formerly reported to its own deputy commissioner. Now they share one.

“They didn’t rip things apart. They didn’t shut things down. It was more subtle than that,” says a former senior NYPD officer in counterterrorism. “It was more a slower operational tempo.”

But looks can be deceiving–and in the realm of intelligence, sometimes they have to be. Sensitive to public perception and embarrassed by media reports that put internal PowerPoints online, the NYPD started caring more about appearances. So while crawlers are gone, the division still keeps an eye on mosques through less intrusive methods. The demographics unit went away, but former U.S. House Intelligence Committee member Jane Harman, a Democrat, speaks admiringly of the NYPD program known as domain awareness, which she describes as “the neighborhood stuff.” The unified command encourages sharing with the FBI, and the NYPD recently stationed a liaison in Australia, bringing its officers overseas to an even dozen.

“What programs has he stopped?” asks former NYPD counterterrorism commanding officer Michael O’Neil of de Blasio. “The critical-response vehicle, where they’re deploying counterterrorism assets around the city, I know it still exists.” As does almost every other program, according to security officials inside and outside the NYPD. Even critics say that at an operational level, the counterterrorism division continues to produce the “gold standard,” handling as many as 100 open cases a day with an agility that federal agencies, burdened as they are by bureaucracy, can admire but not duplicate.

“For the most part, Bill Bratton is continuing what went on before,” says Peter King, a Long Island Republican who chairs the U.S. House Intelligence Subcommittee. “They’re still very aggressive.” Not that he absolves the liberal mayor. “I think it would be easier,” King adds, “if the mayor had been more publicly supportive.”

In the end, that may be the key difference. A softer tone does no favors for the NYPD’s efforts to deter attacks by projecting toughness. And insiders say counterterrorism operatives are especially attuned to the view at the top.

“Before 9/11, there was an expression, ‘If the seventh floor wasn’t enabling some risk taking, it wasn’t taken,'” says Frank Cilluffo, a former top State Department counterterrorism official, referring to the CIA director’s suite. “I’m not talking about cowboy-type risks. People need to know they’ve got their political leaders behind them. I think Bloomberg woke up every day thinking about these issues. I think de Blasio has come around, but he started off on the back foot.”

NYPD counterterrorism chief John Miller calls the mayor “fully supportive of everything we’re doing” and notes that the tempo is brisker than ever now that ISIS “has mass-marketed the idea of terrorism.” In response, de Blasio in June unveiled a city budget calling for 1,300 new officers to be added to the 35,000-strong NYPD. Of those, 300 would go to counterterrorism, trained for the kind of attacks seen in Paris and Mumbai. It also helps that the NYPD was alert to self-starting lone wolves long before ISIS exploited social media, when the division operated with a freewheeling urgency that one former officer likened to the wartime OSS before it became the CIA.

“When we started counterterror, it was right after 9/11. We were really aggressive. People got it,” O’Neil says. Attitudes about surveillance have since grown more nuanced–something smart counterterrorism operatives ignore at their peril. Police, after all, need to build trust with their communities, especially the ones that might get wind of terrorism plots. “I think de Blasio’s moves could end up being a positive,” says Harman. Indeed, much is riding on it.

More Must-Reads from TIME

- Donald Trump Is TIME's 2024 Person of the Year

- Why We Chose Trump as Person of the Year

- Is Intermittent Fasting Good or Bad for You?

- The 100 Must-Read Books of 2024

- The 20 Best Christmas TV Episodes

- Column: If Optimism Feels Ridiculous Now, Try Hope

- The Future of Climate Action Is Trade Policy

- Merle Bombardieri Is Helping People Make the Baby Decision

Contact us at letters@time.com