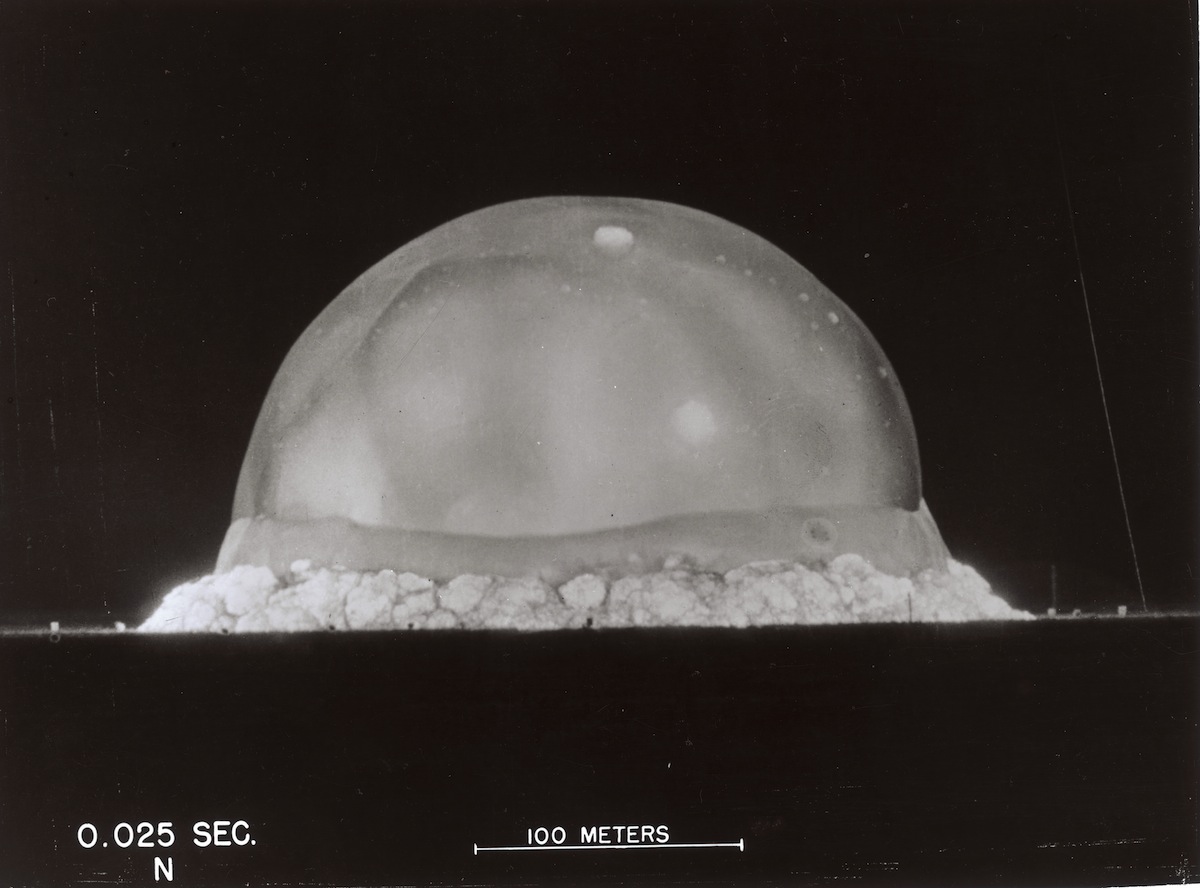

The Trinity nuclear weapon test—the first time an atomic bomb was detonated, exactly 70 years ago on July 16, 1945—is famous today for J. Robert Oppenheimer’s observation “I am become Death” and for the world-changing events that followed the successful explosion. At the time, however, it was the opposite of famous: one journalist attended (from the New York Times) but, for weeks, officials explained away the explosion with a phony cover story.

By that September, however, the U.S. was ready to show off the New Mexico site of the blast.

The Sept. 17, 1945, issue of TIME reported that the Army had brought 31 reporters to see “the first awesome footprint of man’s newest genie” and that the intervening weeks had not lessened its visual impact:

Seen from the air, the crater itself seems a lake of green jade shaped like a splashy star and set in a sere disc of burnt vegetation half a mile wide. From close up the “lake” is a glistening incrustation of blue-green glass 2,400 ft. in diameter, formed when the molten soil solidified in air. The glass takes strange shapes—lopsided marbles, knobbly sheets a quarter-inch thick, broken, thin-walled bubbles, green, wormlike forms.

In the glass lake’s center, directly beneath the bomb’s exploding point, is a crater of bare earth about 15 ft. deep and 300 ft. across. Scientists told newsmen the earth here was pushed downward ten feet by the explosion’s force. Stumps of the four reinforced-concrete tower pillars that supported the bomb still stand in the crater, flaked and twisted. The rest of the tower has vanished into vapor.

But that news junket wasn’t just a matter of showing off the weapons’ power. Rather, it was a concerted public relations effort to counter news out of Japan that the bombs had made Hiroshima and Nagasaki unsafe in the long term. In New Mexico, however, it appeared that the vegetation in the area was continuing to grow healthily. Even though reporters were asked to wear protective shoes and to stay away from still-radioactive “hot spots” in the actual detonation crater, the Army aimed to prove that the lingering effects of the bomb were limited. After all, would they be bringing journalists to walk around near the Trinity site if that weren’t the case?

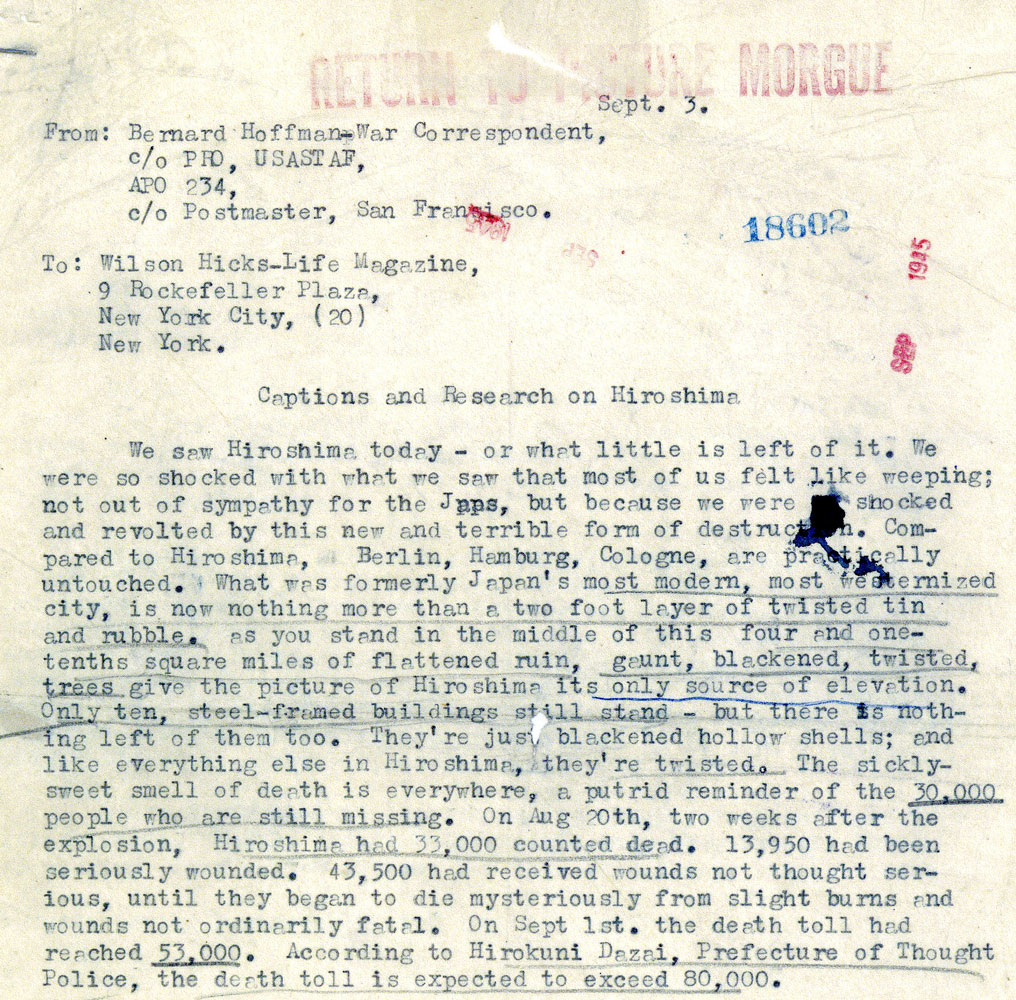

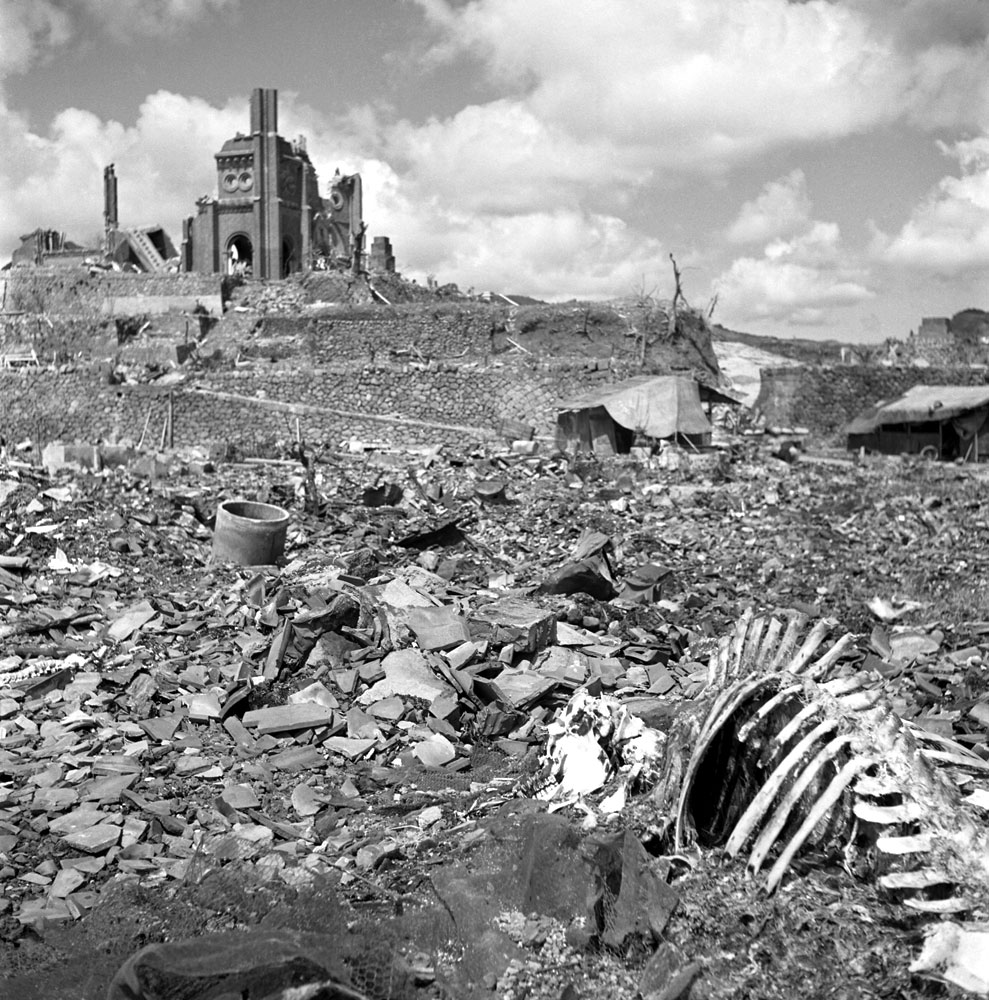

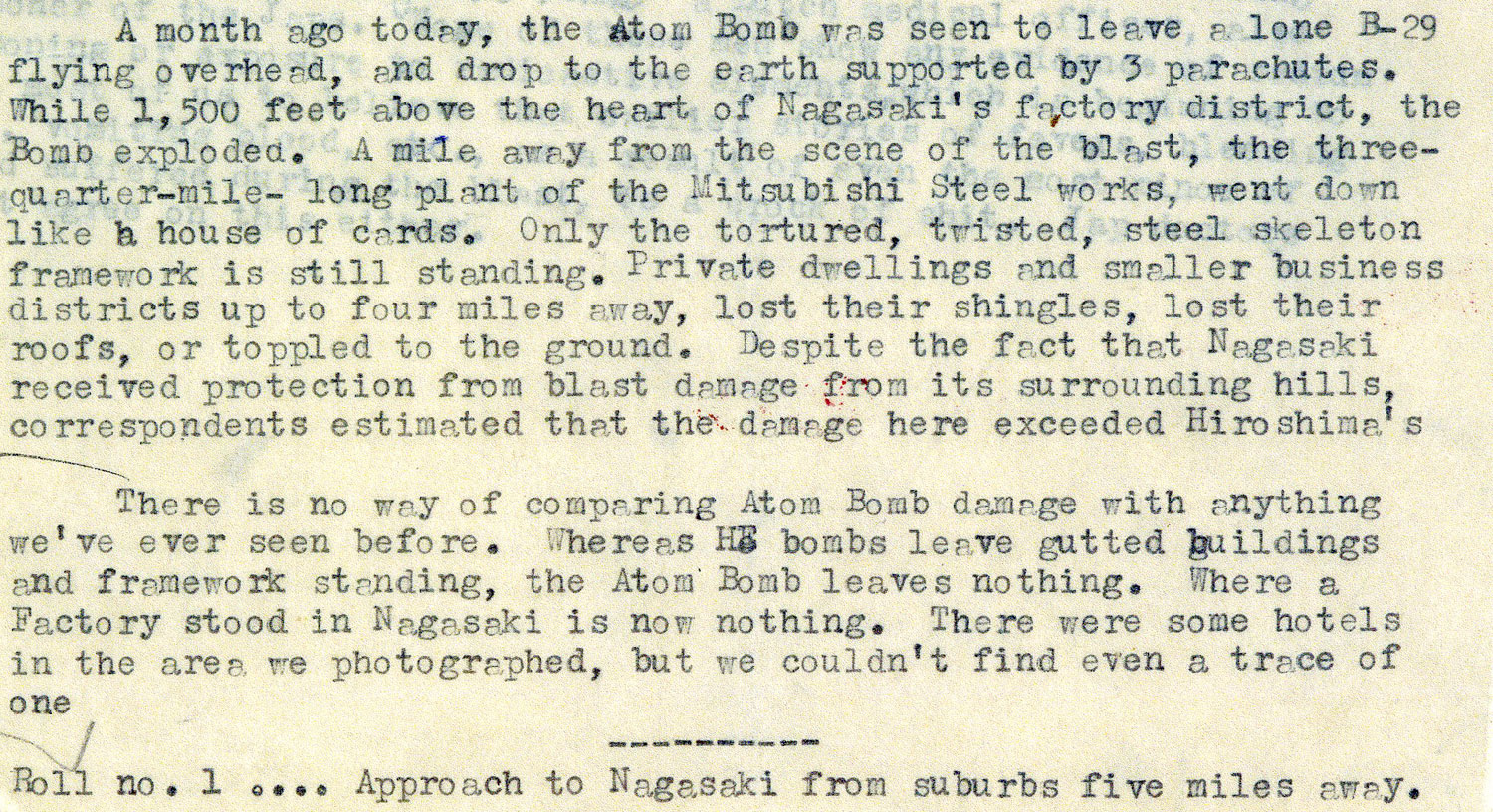

Just as the reporters were able to visit the New Mexico test site, citizens of Hiroshima and Nagasaki were eventually able to return to their cities. A variety of factors, such as the tonnage of the bombs and the height of detonation, meant that the radiation dissipated more quickly than might have otherwise been the case. However, the damage to those who were present before that point in time was immense. Many of those who seemed to have survived unscathed fell ill later.

In fact, that very same issue of TIME carried another story, in the health section rather than the science section, with a report from a Dutch doctor who happened to be a prisoner of war in Japan at the time of the bombings. He told TIME about people with a set of strange symptoms—swelling, hemorrhages, fever, internal bleeding. “Many (though not all) of the bomb victims who seemed to be recovering,” the magazine reported, “collapsed and died several weeks later.”

But, seven decades later, it now seems that scientists might have been wrong about the residual radiation all along: last September, the U.S. National Cancer Institute announced plans to study a possible link between the Trinity test and high cancer rates in the area.

Hiroshima and Nagasaki: Photos From the Ruins

More Must-Reads from TIME

- Cybersecurity Experts Are Sounding the Alarm on DOGE

- Meet the 2025 Women of the Year

- The Harsh Truth About Disability Inclusion

- Why Do More Young Adults Have Cancer?

- Colman Domingo Leads With Radical Love

- How to Get Better at Doing Things Alone

- Michelle Zauner Stares Down the Darkness

Write to Lily Rothman at lily.rothman@time.com