A few giants towered above the others on the fiction best-seller lists in the early 1960s: James Michener, Irving Wallace, Herman Wouk, Irving Stone, Saul Bellow, John O’Hara, Leon Uris, their titles flashing their authors’ intentions to loosen their ties, put down their bourbons, tamp out their cigarettes or pipes and confront their Smith Corona typewriters long enough to chisel truth from granite: Advise and Consent, The Agony and the Ecstasy, The Ugly American, The Source, Armageddon. Into this manly realm with its scent of Old Spice and Aqua Velva, in the summer of 1960, tiptoed a young slip of a book with an artsy cover and the odd name To Kill a Mockingbird. It told, in an elliptical and poetical and roundabout way, the coming-of-age story of a motherless little Alabama white girl whose daddy, a country lawyer, defies Depression-era social convention and takes on the case of a local black man falsely accused of rape.

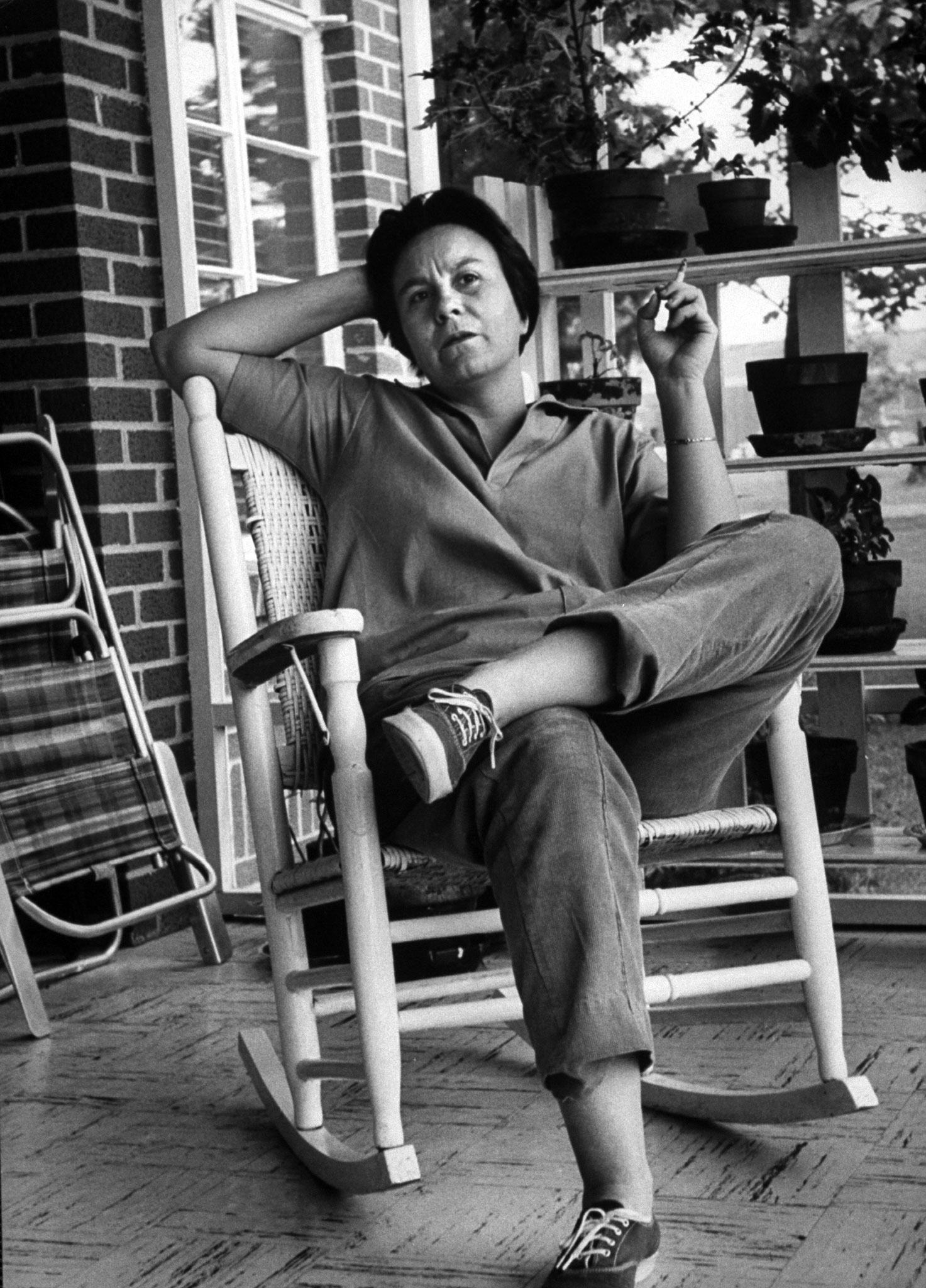

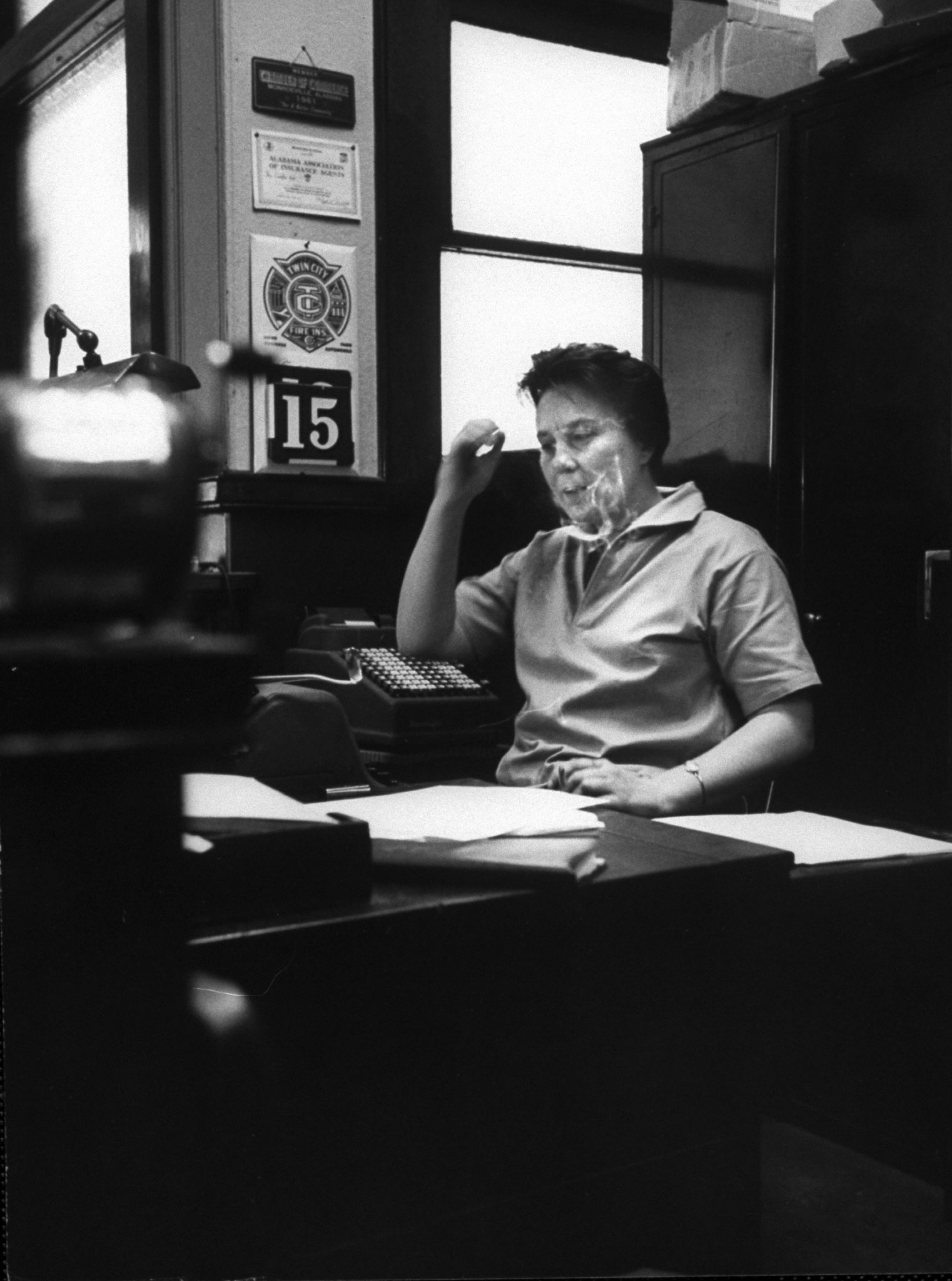

No one had heard of the author, who turned out to be—despite the mannish name of Harper Lee—a tall-ish southern white woman in slacks, a tucked-in button-down shirt with an open collar, flat shoes and a short hair-cut. She’d moved to New York City from Alabama a decade earlier to work as an airline reservation agent. Nelle Harper Lee (she dropped the “Nelle” for publication, fearing Yankees would bungle the name) was born in Monroeville, Alabama, in 1926, when the population of the town numbered about 1,300 citizens and would soon include a boy one and a half years her senior named Truman Streckfus Persons. He would become her lifelong friend and would publish his books under the name Truman Capote.

Nelle’s mother was a homemaker and her father a state legislator and country lawyer who once defended two black men accused of murdering a white storekeeper; like Atticus Finch, the hero of To Kill a Mockingbird, Amasa Coleman Lee proved unable to protect either his clients’ good names or their lives. The author’s beloved much-older sister, Alice Finch Lee, was a principled small-town lawyer too, who, like their father, and like the fictional Atticus Finch, attempted to appraise the folks of thoroughly segregated Alabama by the content of their characters.

“I never expected any sort of success with Mockingbird,” Harper Lee told one early interviewer. “I was hoping for a quick and merciful death at the hands of the reviewers, but at the same time, I sort of hoped some- one would like it enough to give me encouragement.”

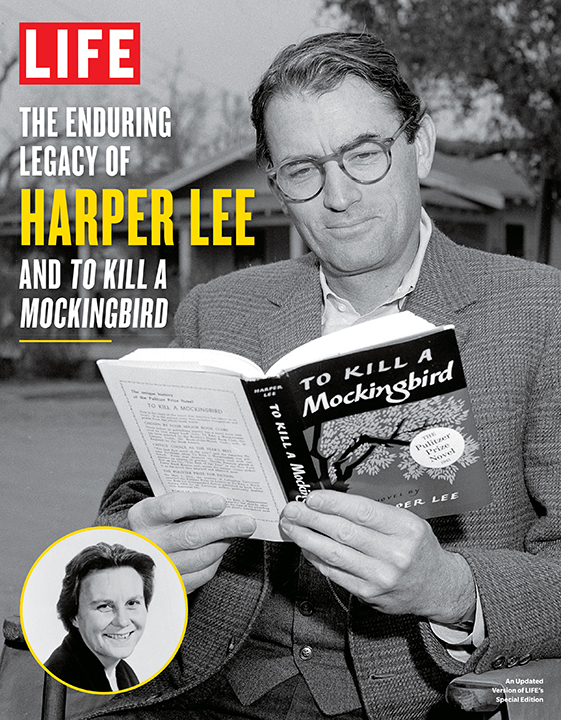

While a few early readers sniffed at the book disparagingly (Flannery O’Connor tartly noted, “It’s interesting that all the folks that are buying it don’t know they are buying a children’s book”); and some mocked Atticus Finch’s relentless goodness and homespun homilies; and others, years later, would lament that this creation of the late 1950s lacked the social enlightenment and moral bravery of true civil rights activism, the author still managed to eke out that bit of encouragement from the book’s reception. To Kill a Mockingbird eventually won the Pulitzer Prize for Fiction in 1961 and rode the best-seller lists for over 80 weeks. Translated into more than 40 languages, selling over 40 million copies, it would become one of the best-selling novels of the 20th century. In the 21st century, it sells a million copies a year. The book was promptly adapted into a beautiful and wildly popular movie in which Gregory Peck immortalized Atticus Finch, won the Academy Award for Best Actor, and became a friend to the author; the movie was nominated for a total of eight Academy Awards and won three. Atticus Finch would be named the American Film Institute’s premier movie hero of the century and would inspire generations of idealistic young people to flood into law schools to become public interest advocates. Mockingbird would pop up at or near the top of every English-language Great Books list composed from the year of its publication on—occasionally beating out the Bible for the No. 1 spot.

After more hoopla than a person could reasonably handle, Harper Lee avoided the spotlight while continuing to live in New York and regularly visiting her family in Monroeville. Miss Nelle (as she’s known locally) moved home for good in 2007 after suffering a stroke and resides in an assisted-living facility.

Following the death of her sister Alice, it was announced that the manuscript of Go Set a Watchman had been found, a find that begat all the current news. The best news may be that people have been redirected to the great book, Harper Lee’s urtext.

Read the rest of this essay in LIFE’s new special edition, The Enduring Legacy of Harper Lee and To Kill a Mockingbird, is available on Amazon.

See Harper Lee's Secluded Alabama Life

![Harper Lee [& Family] Harper Lee visiting her hometown, Monroeville, Alabama, in 1961.](https://api.time.com/wp-content/uploads/2015/03/150312-harper-lee-04.jpg?quality=75&w=2400)

More Must-Reads from TIME

- Why Trump’s Message Worked on Latino Men

- What Trump’s Win Could Mean for Housing

- The 100 Must-Read Books of 2024

- Sleep Doctors Share the 1 Tip That’s Changed Their Lives

- Column: Let’s Bring Back Romance

- What It’s Like to Have Long COVID As a Kid

- FX’s Say Nothing Is the Must-Watch Political Thriller of 2024

- Merle Bombardieri Is Helping People Make the Baby Decision

Contact us at letters@time.com