Military commanders like to say that “quantity has a quality all its own.” It’s a shorthand way of saying that greater numbers of inferior weapons or troops often can beat smaller, superior forces. Given that Monday marks the first birthday of the declaration of the Islamic State of Iraq and Greater Syria, it’s also worth noting that the passage of time, too, has a quality all its own.

The quantity of time counts, as days turn into weeks, and months have become a year. Time isn’t an inert presence, either on the physical battlefield or in the war of ideas. It’s a measure of will, a magnet to attract followers, and a manifestation of reality. Bottom line: persistence produces power.

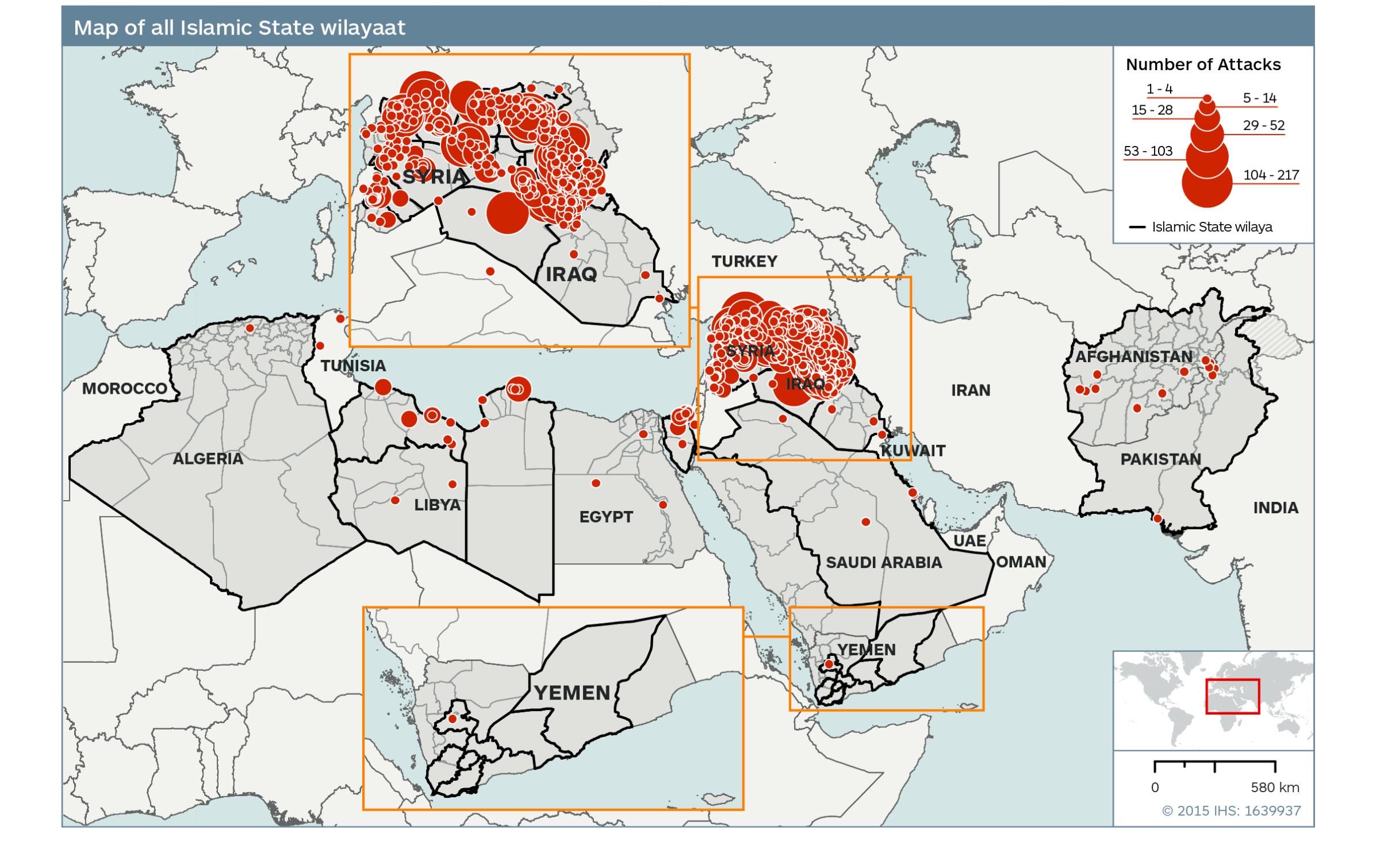

This isn’t good. The Pentagon has adopted a go-slow approach, with its modest air campaign and turgid training schedule, in part to prod Iraq to do the fighting. That’s fine, so long as you believe ISIS is a slow-growing tumor, confined to Iraq and Syria. But as last Friday’s attacks in France, Kuwait and Tunisia that killed at least 60 make clear, it’s a malignancy that’s spreading.

“They’ve been able to hold ground for a year,” says retired Marine general James Mattis, who served as chief of U.S. Central Command from 2010 to 2013. “The longer they hold territory it become this radioactive thing, just spewing out this stuff as fighters go there and then come home again.”

“Listen to your caliph and obey him,” ISIS spokesman Abu Mohamed al-Adnani said of ISIS leader Abu Bakr al-Baghdadi in a recording released June 29, 2014. “Support your state, which grows every day.”

Chillingly, al-Adnani issued a call last Tuesday calling on Muslims to mark the holy month of Ramadan by making it “a month of disasters for the kuffar”—non-Muslims. He pledged those carrying out such attacks “tenfold” rewards in heaven in exchange for their martyrdom. Last week’s attacks followed. ISIS took responsibility for the beachfront attack in Tunisia that killed at least 38; an ISIS affiliate claimed credit for the blast at a Kuwait City mosque that took 27 lives; the suspect in the French attack reportedly told police of his ties to the Islamic State after decapitating his employer.

After a year in existence, ISIS continues to keep its grip on the huge swatch of land straddling what used to be the border between eastern Syria and western Iraq. “After awhile, possession is nine-tenths of legitimacy,” Anthony Cordesman, a military scholar at the Center for Strategic and International Studies, says of ISIS’s first anniversary. “Just being there, visible, over time gives you more and more influence and ability to create more extremists.”

This represents a new kind of threat. “The Islamic State is not an insurgency like the United States fought from 2003 until its departure from Iraq,” Rand Corp. analyst David Johnson notes in the latest issue of Parameters, the Army’s professional journal. “Rather, it is an aspiring proto-state bent on taking and holding territory.”

The U.S. actually has been fighting ISIS and its forebears for years. “Washington continues to fail to recognize the persistence of this organization going back to the declaration of what was then called the Islamic State of Iraq,” Brian Fishman of West Point’s Combating Terrorism Center told the House Armed Services Committee last Wednesday. “We don’t often recognize our long history of fighting ISIS, but we have effectively been fighting this organization for a decade already.”

As ISIS grew and began controlling greater swaths of Iraq and Syria, there was a sense its days were numbered. Following its seizure of Mosul, Iraq’s second-largest city, just over a year ago, Pentagon officials repeatedly said that Iraqi forces, perhaps aided by small numbers of U.S. troops accompanying them to call in air strikes, would take back the city sometime in the first half of 2015. That hasn’t happened. And for every Tikrit that Iraqi forces, aided by Iranian-backed Shi’a militias, have taken from ISIS by military force, ISIS has attacked and occupied a city like Ramadi, capital of Iraq’s Anbar province.

Despite President Obama’s pledge to “degrade and destroy” ISIS last summer, little has changed. “Very little consequential territory has been reclaimed,” says retired general Jack Keane, who served as the Army’s second-ranking officer from 1999 to 2003. “ISIS still enjoys freedom of maneuver to attack at will, whenever and wherever it pleases.”

While the U.S.-led air campaign has led pretty much to a stalemate on the ground, ISIS’s survival has attracted supporters to its ranks, and led others around the world to claim membership. “What we see very frequently in Afghanistan, with respect to [ISIS], is a rebranding of people who are already in the battlefield,” Defense Secretary Ashton Carter said Thursday in Belgium. They’re donning the ISIS label because “they regard as a better replacement for names they’ve had in the past.”

ISIS’s continuing existence is also generating American recruits, according to an alert last month from the Department of Homeland Security to U.S. law enforcement agencies shortly after police killed a pair planning to shoot up a “draw Muhammad” contest in Garland, Texas. “We judge … that [ISIS’s] messaging is resonating with US-based violent extremists due to its championing of a multifaceted vision of a caliphate,” the agency warned. A key reason for its success in attracting followers, DHS added, is “the perceived legitimacy of its self-proclaimed re-establishment of the caliphate.”

Every day that the undefeated caliphate persists boosts the chances that its followers will strike targets in the U.S. “The most important way to discredit the appeal of their ideology is by military defeat,” Michael Eisenstadt of the Washington Institute for Near East Policy told that armed services panel hearing last week. “If they’re not holding terrain, if there is no caliphate,” he said. “There is no Islamic utopia.”

More Must-Reads from TIME

- Cybersecurity Experts Are Sounding the Alarm on DOGE

- Meet the 2025 Women of the Year

- The Harsh Truth About Disability Inclusion

- Why Do More Young Adults Have Cancer?

- Colman Domingo Leads With Radical Love

- How to Get Better at Doing Things Alone

- Michelle Zauner Stares Down the Darkness

Contact us at letters@time.com