In the last few weeks, Rachel Dolezal—the Spokane, Wash., NAACP leader who recently left her post after being outed as white though saying that she identified as black—led many to examine the relationship between skin color and racial-justice activism. Writing for TIME, Kareem Abdul-Jabbar noted that, despite her ethnic background, Dolezal “has proven herself a fierce and unrelenting champion for African-Americans politically and culturally.”

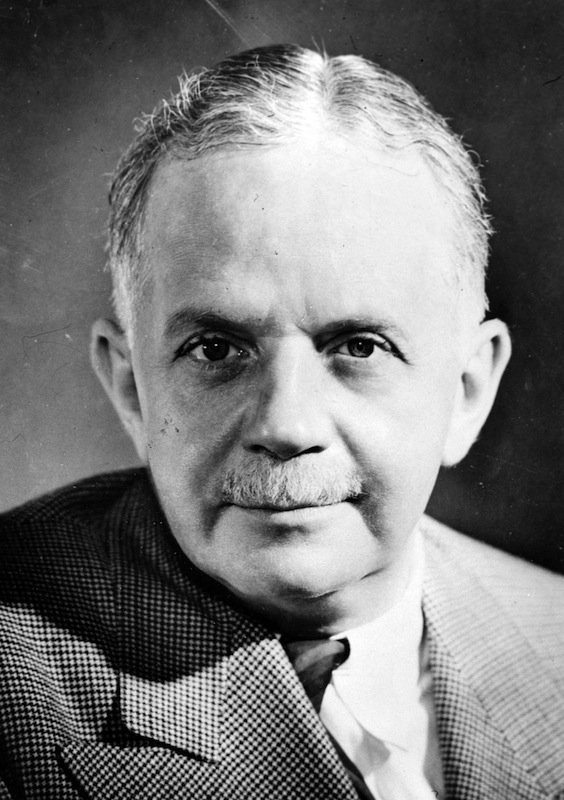

Regardless of what one thinks of Dolezal, whose story only grew increasingly complicated, there’s plenty of historical evidence that looks aren’t the most important thing when it comes to championing equality. For proof, look no further than Walter Francis White, who was born on this day, July 1, in 1893. White ushered the NAACP into the Civil Rights era, serving as its leader more than 20 years, from 1931 until his death in 1955.

In the dated language of the day, his obituary in the New York Times referred to him as “a Negro by choice,” explaining:

Only five-thirty-seconds of his ancestry was Negro. His skin was fair, his hair blond, his eyes blue and his features Caucasian. He could easily have joined the 12,000 Negroes who pass the color-line and disappear into the white majority every year in this country.

But if Walter White was a “Negro by choice,” it wasn’t a choice made arbitrarily—and his first-hand knowledge of the facts of life for African Americans was personal, deep and real. Both of his parents had been born into slavery, and although they went on to earn college degrees and pursue middle-class careers as a postal worker (his father) and teacher (his mother), they endured ruthless discrimination throughout their lives. As TIME elaborated in 1938:

[White] remembers that his father’s house was almost burned down during an Atlanta race riot in his childhood. He recalls too that his father died in agony when the surgeons of the white ward of an Atlanta hospital, to which he had been mistakenly taken for an emergency operation, balked upon learning his race and insisted on shipping him in the rain to the Negro ward across the street.

While he was a highly esteemed activist and a powerful champion of anti-lynching legislation, he was occasionally rebuffed in the black community by those who mistook him for a white outsider. In his autobiography, A Man Called White, he recalls the day he accidentally stepped on the toes of another black man on a subway platform. The man lashed out bitterly, saying, “Why don’t you look where you’re going? You white folks are always trampling on colored people.”

White knew as well as anyone that his life would have been vastly simpler if he had capitalized on his skin color and, as the Times put it, “disappear[ed] into the white majority.” But he refused to turn his back on his heritage — or on those who couldn’t so easily disappear from the injustices of the Jim Crow era.

As he put it in his book:

I am not white. There is nothing within my mind and heart which tempts me to think I am. Yet I realize acutely that the only characteristic which matters to either the white or the colored race—the appearance of whiteness—is mine. There is magic in a white skin; there is tragedy, loneliness, exile, in a black skin.

Through his activism White helped ease some of that tragedy, loneliness, and exile. After he died, TIME called him a “dogged lobbyist” who had “a major hand in virtually every civil-rights law enacted” during his NAACP leadership. Indeed, TIME concludes that 1955 obituary with the observation, “As Walter White died, his old enemy Jim Crow was dying too.”

Read a 1938 profile of Walter White, here in the TIME archives: Black’s White

More Must-Reads from TIME

- Why Trump’s Message Worked on Latino Men

- What Trump’s Win Could Mean for Housing

- The 100 Must-Read Books of 2024

- Sleep Doctors Share the 1 Tip That’s Changed Their Lives

- Column: Let’s Bring Back Romance

- What It’s Like to Have Long COVID As a Kid

- FX’s Say Nothing Is the Must-Watch Political Thriller of 2024

- Merle Bombardieri Is Helping People Make the Baby Decision

Contact us at letters@time.com