U.S. and Chinese warships battle at sea, firing everything from cannons to cruise missiles to lasers. Stealthy Russian and American fighter jets dogfight in the air, with robotic drones flying as their wingmen. Hackers in Shanghai and Silicon Valley duel in digital playgrounds. And fights in outer space decide who wins below on Earth. Are theses scenes from a novel or what could actually take place in the real world the day after tomorrow? The answer is both.

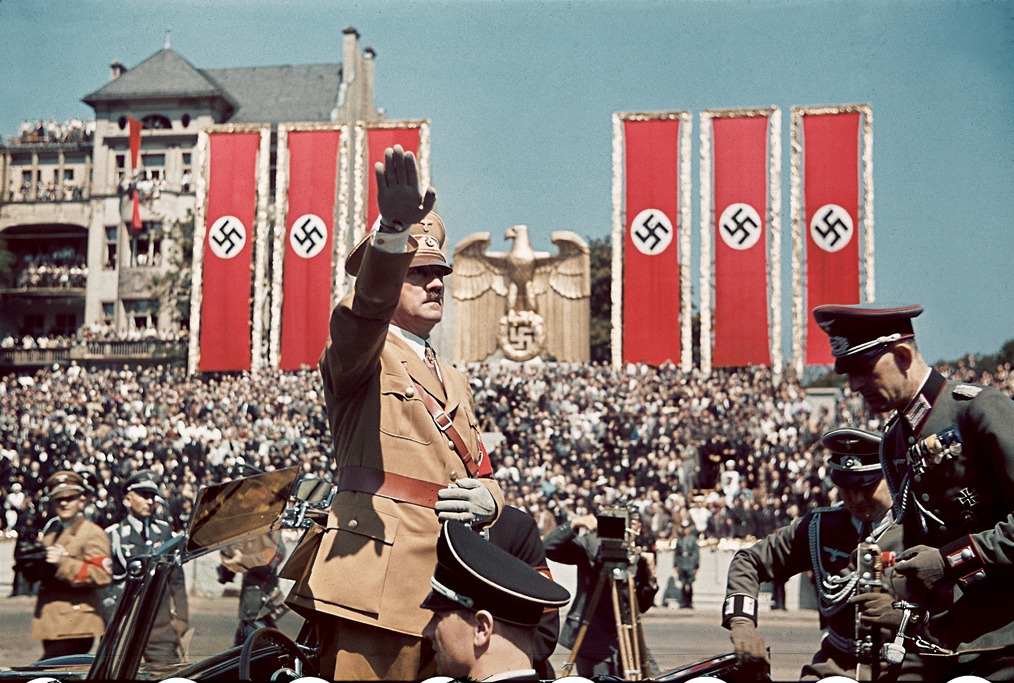

Great power conflicts defined the 20th century: Two world wars claimed tens of millions of lives, and the Cold War that followed shaped everything from geopolitics to sports. But at the start of the 21st century, the ever-present fear of World War III seemed to be in our historic rearview mirror.

Yet that risk of the past has made a dark comeback. Russian land grabs in Ukraine and constant flights of bombers decorated with red stars probing Europe’s borders have put NATO at its highest levels of alert since the mid 1980s. In the Pacific, the U.S. and a newly powerful and assertive China are engaged in a massive arms race. China built more warships and warplanes than any other nation during the last several years, while the Pentagon just announced a strategy to “offset” it with a new generation of high-tech weapons. Indeed, it’s likely China’s alleged recent hack of federal records at the Office of Personnel Management was not about cyber crime, but a classic case of what is known as “preparing the battlefield,” gaining access to government databases and personal records just in case.

The worry is that the brewing 21st century Cold War with China and its junior partner Russia could at some point turn hot. “A U.S.-China war is inevitable” recently warned the Communist Party’s official People’s Daily newspaper after recent military face-offs over rights of passage and artificial islands built in disputed territory. This may be a bit of posturing both for U.S. policymakers and a highly nationalist domestic audience: A 2014 poll by the Perth U.S.-Asia center found that 74% of Chinese think their military would win in a war with the U.S. But it points to how the global context is changing. Many Chinese officers have begun to lament out loud what they call “peace disease,” their term for never having served in combat.

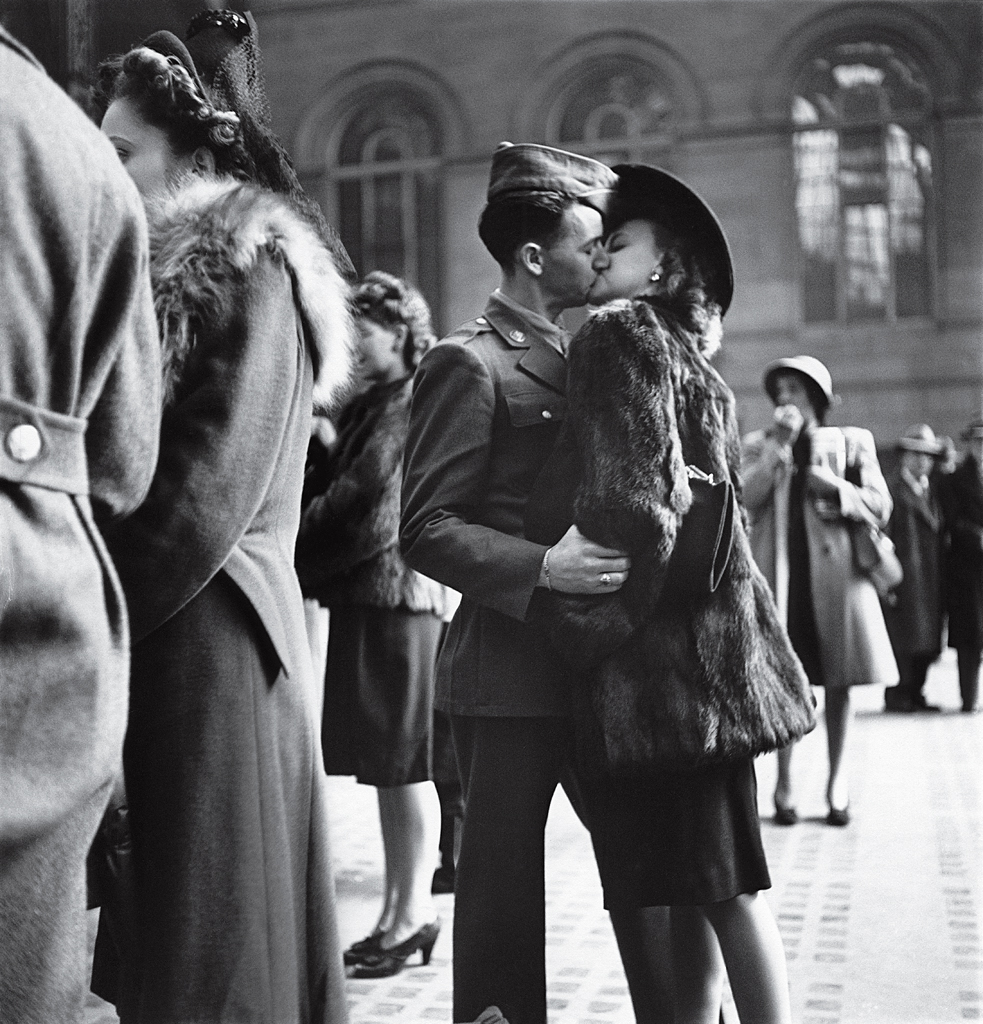

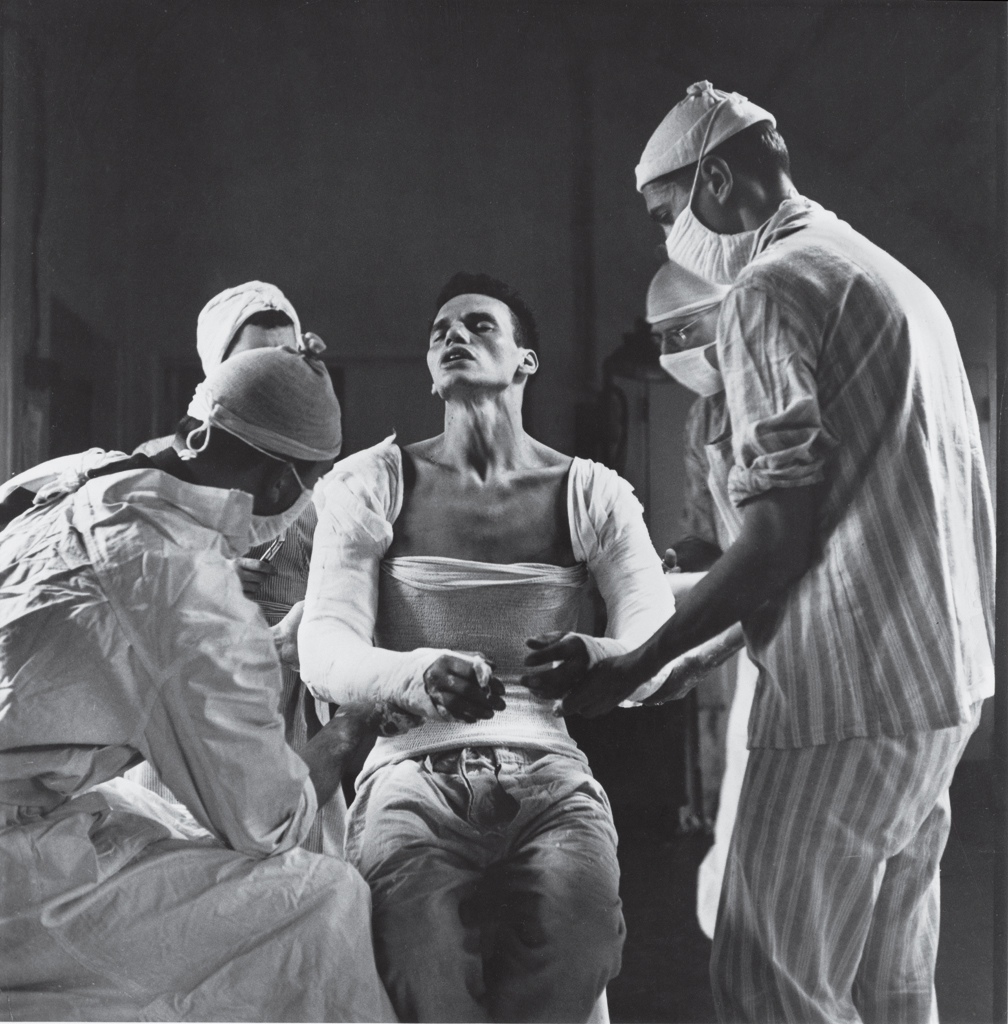

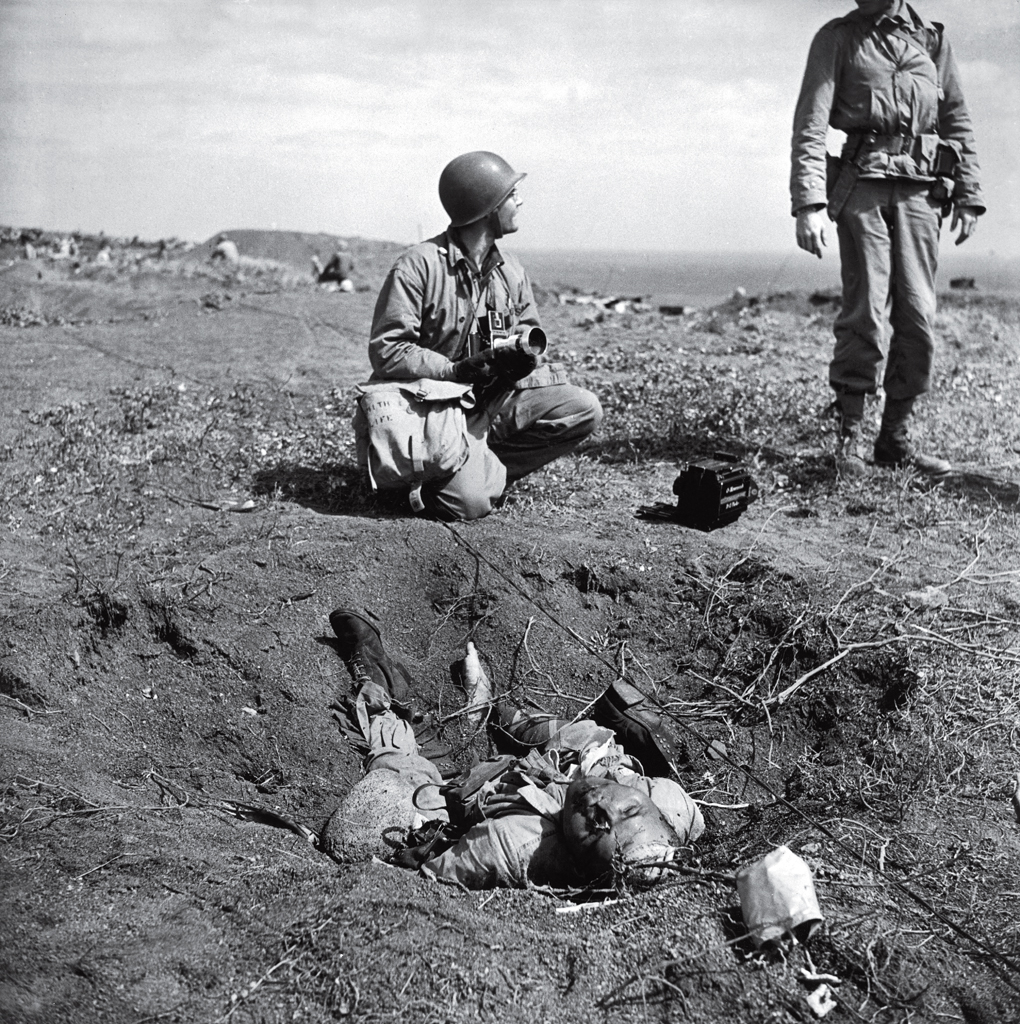

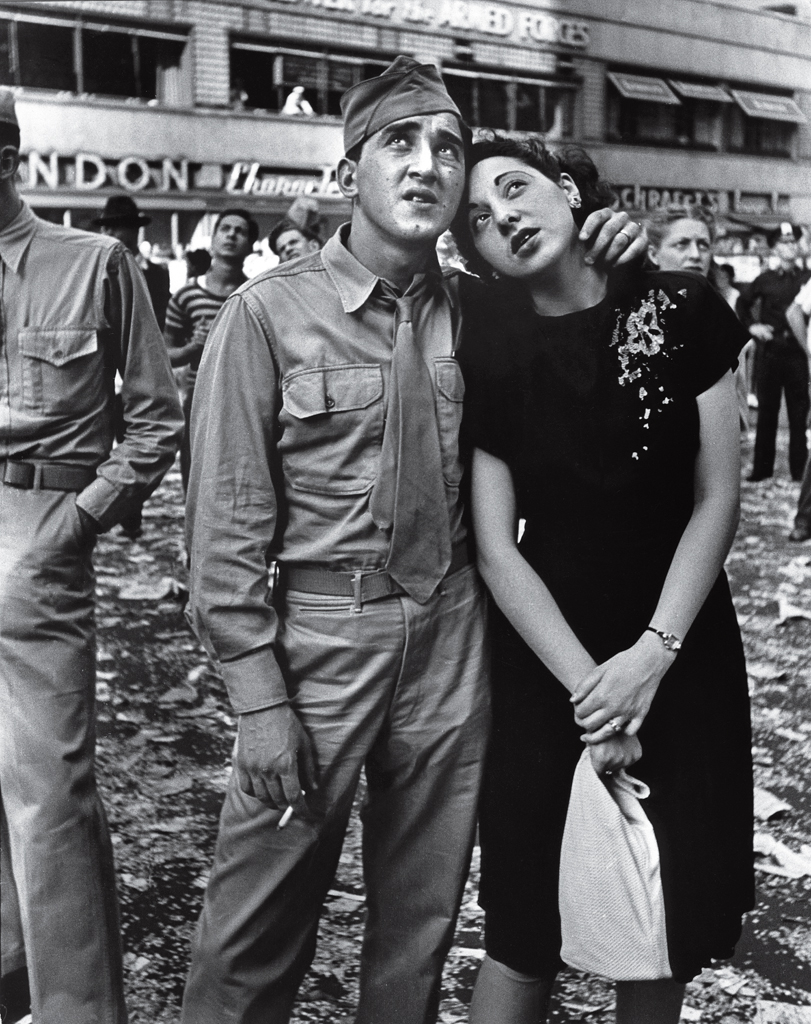

World War II: Photos We Remember

Wars start through any number of pathways: One world war happened through deliberate action, the other was a crisis that spun out of control. In the coming decades, a war might ignite accidentally, such as by two opposing warships trading paint near a reef not even marked on a nautical chart. Or it could slow burn and erupt as a reordering of the global system in the late 2020s, the period at which China’s military build up is on pace to match the U.S.

Making either scenario more of a risk is that military planners and political leaders on all sides assume their side would be the one to win in a “short” and “sharp” fight, to use common phrases. It would be anything but.

A great power conflict would be quite different from the small wars of today that the U.S. has grow accustomed to and, in turn, others think reveal a new American weakness. Unlike the Taliban or even Saddam’s Iraq, great powers can fight across all the domains; the last time the U.S. fought a peer in the air or at sea was in 1945. But a 21st century fight would also see battles for control of two new domains.

The lifeblood of military communications and control now runs through space, meaning we’d see humankind’s first battles for the heavens. Similarly, we’d learn “cyber war” is far more than stealing Social Security Numbers or e-mail from gossipy Hollywood executives, but the takedown of the modern military nervous system and Stuxnet-style digital weapons. Worrisome for the U.S. is that last year, the Pentagon’s weapons tester found nearly every single major weapons program had “significant vulnerabilities” to cyber attack.

A total mindshift is required for this new reality. In every fight since 1945, U.S. forces have been a generation ahead in technology, having uniquely capable weapons like nuclear-powered aircraft carriers. It has not always translated to decisive victories, but it has been an edge every other nation wants. Yet U.S. forces can’t count on that “overmatch” in the future. These platforms are not just vulnerable to new classes of weapons like long-range missiles, but China, for example, overtook the EU in R&D spending last year and is on pace to match the U.S. within five years, with new projects ranging from the world’s fastest supercomputers to three different long-range drone-strike programs. And now off-the-shelf technologies can be bought to rival even the most advanced tools in the U.S. arsenal. The winner of a recent robotics test, for instance, was not a U.S. defense contractor but a group of South Korea student engineers.

An array of science-fiction-like technologies would likely make their debut in such a war, from AI battle management systems to autonomous robotics. But unlike the ISIS’s of the world, great powers can also go after high-tech’s new vulnerabilities, such as by hacking systems and knocking down GPS. The recent steps taken by the U.S. Naval Academy illustrate where things might be headed. It added a cybersecurity major to develop a new corps of digital warriors, and also requires all midshipmen learn celestial navigation, for when the high tech inevitably runs into the age old fog and friction of war.

While many leaders on both sides think any clash might be geographically contained to the straights of Taiwan or the edge of the Baltic, these technological and tactical shifts mean such a conflict is more likely to reach into each side’s homelands in new ways. Just as the Internet reshaped our notions of borders, so too would a war waged partly online.

The civilian players would also be different than those in 1941. The hub of any war economy wouldn’t be Detroit. Instead, tech geeks in Silicon Valley and shareholders in Bentonville, Ark., would wrestle with everything from microchip shortages to how to retool the logistics and allegiance of a multinational company. The new forms of civilian conflict actors like Blackwater private military firms or Anonymous hacktivist groups are unlikely to just sit out the fight.

A Chinese officer argued in a regime paper, “We must bear a third world war in mind when developing military forces.” But there is a far different attitude in Washington’s defense circles. As the U.S. Chief of Naval Operations worried last year, “If you talk about it openly, you cross the line and unnecessarily antagonize. You probably have a sense about how much we trade with that country, it’s astounding.”

This is true, but both the historic trading patterns between great powers before each of the last world wars and the risky actions and heated rhetoric out of Moscow and Beijing over the last year demonstrate it is no longer useful to avoid talking about the great power rivalries of the 21st century and the dangers of them getting out of control. We need to acknowledge the real trends in motion and the real risks that loom, so that we can take mutual steps to avoid the mistakes that could create such an epic fail of deterrence and diplomacy. That way we can keep the next world war where it belongs, in the realm of fiction.

More Must-Reads From TIME

- The 100 Most Influential People of 2024

- Coco Gauff Is Playing for Herself Now

- Scenes From Pro-Palestinian Encampments Across U.S. Universities

- 6 Compliments That Land Every Time

- If You're Dating Right Now , You're Brave: Column

- The AI That Could Heal a Divided Internet

- Fallout Is a Brilliant Model for the Future of Video Game Adaptations

- Want Weekly Recs on What to Watch, Read, and More? Sign Up for Worth Your Time

Contact us at letters@time.com