Correction appended Monday, June 30.

This past winter was one of the worst on record for the northeast, but the snow didn’t stop U.S. homeowners from investing in solar paneling. According to the Solar Energy Industries Association (SEIA), 2015’s first quarter broke records, with 66,440 new solar systems getting installed in the first three months of the year. That brings the total U.S. households with solar to approximately 700,000.

“These are not just solar enthusiasts anymore,” says Tom Kimbis, SEIA’s vice president of executive affairs. “The vast majority of residential installations — by a long shot — are done because solar is affordable and it’s saving money.”

Several factors are driving solar’s ever-increasing adoption, from improved technologies and falling installation costs to a generous federal tax credit that’s coming to a close in 2016. As a result, how residential solar power works is more than just the conversion of sunbeams into kilowatts. To truly understand it, you have to follow the light from the solar panel all the way to your wallet.

Step 1: Rack ‘Em Up

Humans have used the sun to heat water for thousands of years, but solar electric power, also called photovoltaic or PV, got its start in the 1950s. Since then, there have been great advances in the technology, which is helping make solar so attractive today.

Solar panels are modules made up of cells, like the kind you see on a solar-powered calculator. A racking system is used to attach the panels to a rooftop. Installers will orient the rack to make sure the module gets the most direct sunlight possible. But if a house’s roof lacks the proper orientation, the modules can be placed in a yard via a ground mounted system instead.

As installers have gained more experience, they’ve become much more efficient at mounting panels. Installations that used to take days now can be done in just hours, one reason the cost of solar has dropped in recent years.

Still, says Kimbis, as with any major home improvement project, you should get bids from multiple installers and compare the results. The solar company should give you an estimate of how much power that system is going to produce based on annual statistics they know from a variety of different factors: the weather in your region, the angle of your roof, and its ordinal orientation, he says. Those factors will determine the size of the system and how much electricity, on average, it will produce every year.

Step 2: Catch Some Rays

“One thing that people notice when they put a solar system on is how silent it is because there aren’t any moving parts,” says Kimbis. The panels and the racking system make up two-thirds of a solar power system; the final piece is the inverter.

An inverter takes the energy captured by the cells and converts it from Direct Current (DC) into Alternating Current (AC). If you think of electrical energy as the movement of electrons, our homes (and the electrical grid) operate on AC because under that standard, electricity can travel for miles without shedding power along the way. On the other hand, DC is much better at storing power, which is why car batteries use it. And soon, homes will be storing their own solar power, too. In February, Tesla CEO Elon Musk announced his company will have home batteries available for installation next summer. Not to be outdone, earlier this month Mercedes-Benz announced it too will be selling home batteries, with deliveries beginning this fall.

But our homes will still require AC power to draw extra energy from and send excess energy back to the grid. So an inverter, which can convert electricity from DC to AC, is required to connect the solar panels to the home’s electrical system. Inverters are typically installed right outside the breaker box, allowing the home to use the solar power first, then if the demand is too high, the home can grab more power off the grid. Conversely, if the solar system is creating more electric energy than the home needs, it can send that power out into the grid, reducing our overall demand on nuclear and fossil fuels. Some places even allow you to sell the excess energy you create back into the grid, an activity known as “net metering” which is attractive to many potential solar customers.

Step 3—Pay Your Bill

In a way, this step should actually come first, but having a good understanding of how solar works will help you better figure out your bill. There are currently three ways homeowners can add solar arrays to their property. The first is by simply purchasing an array and having it installed. The second is by leasing a solar array from a company that installs and maintains it, and the third is through a Power Purchase Agreement. Each method has its own variables and there are many companies operating in the space, so it’s impossible to generalize about which solution is the best one for you.

Purchasing your own solar array typically involves the biggest up-front investment, but can also be the most financially advantageous way to go. Homeowners who buy their own system can receive a federal investment tax credit worth 30% of the cost of their system. Kimbis estimates that a “nice sized system” would cost around $15,000, but for that price, $4,500 would be applied as a credit to the homeowner’s federal tax bill. Still, with this benefit also comes the maintenance and upkeep of the system moving forward. But most panels have a warranty of around 25 years, and the inverter can last up to 30 years — which leads to a very important point: If you have an aging, tired roof, you might want to wait until it’s replaced before you go solar at all.

Leasing takes the sting out of equipment and installation costs, but it spreads them out over a long term deal, similar to an auto lease. “In general the lease option comes in monthly payments to the system, and then whatever electricity is generated is yours to keep,” says Kimbis. But because a company technically owns the panels, this method won’t get you the same direct tax benefits as if you bought your own system. You could reap the benefits of your solar company claiming a 30% federal tax credit, but that depends on the company passing those savings down to you.

Power purchase agreements (PPAs) are very similar to how people pay their electric bills today — the equipment is owned by a third party, and customers are only charged for the kilowatt-hours of solar power that they use. In fact, some companies will simplify your solar and electric billing so you just receive one bill, to save on transaction costs. But overall, the lack of an up-front installation cost makes PPAs a very attractive proposition for solar-seeking homeowners. In fact, says Kimbis, overall, the majority of solar customers enter leases and PPAs instead of buying their own equipment outright.

Whichever setup you select, keep in mind that no two solar setups — just like no two homes — are the same. Even if two homeowners got the same equipment and financing deal from the same company, shadows and geography could create differing solar yields. “People’s usage varies, so their electricity demand varies in their house,” says Kimbis.

The question of whether solar is right for you depends on how much you’re paying for electricity now, and that varies based on where you live — homes near cheap hydro-electric dams or in the heart of coal country may not benefit like more remote homes with higher fuel costs.

But the question is no longer about the technology, says Kimbis. “Home owners should feel comfortable that the technology itself has been proven,” he says. “We have reached sort of a tipping point here with solar being very affordable, being reliable, and a clean energy source.”

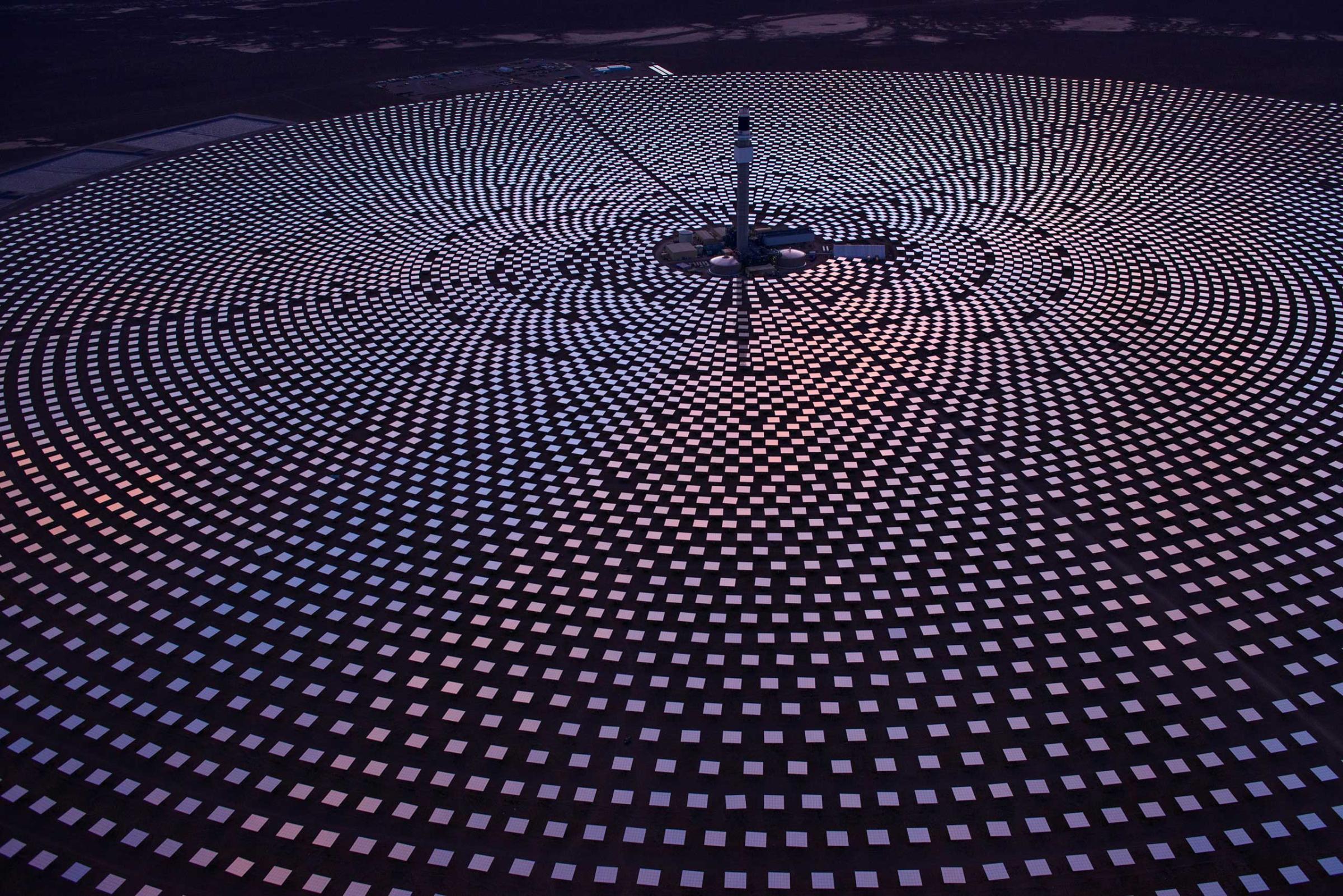

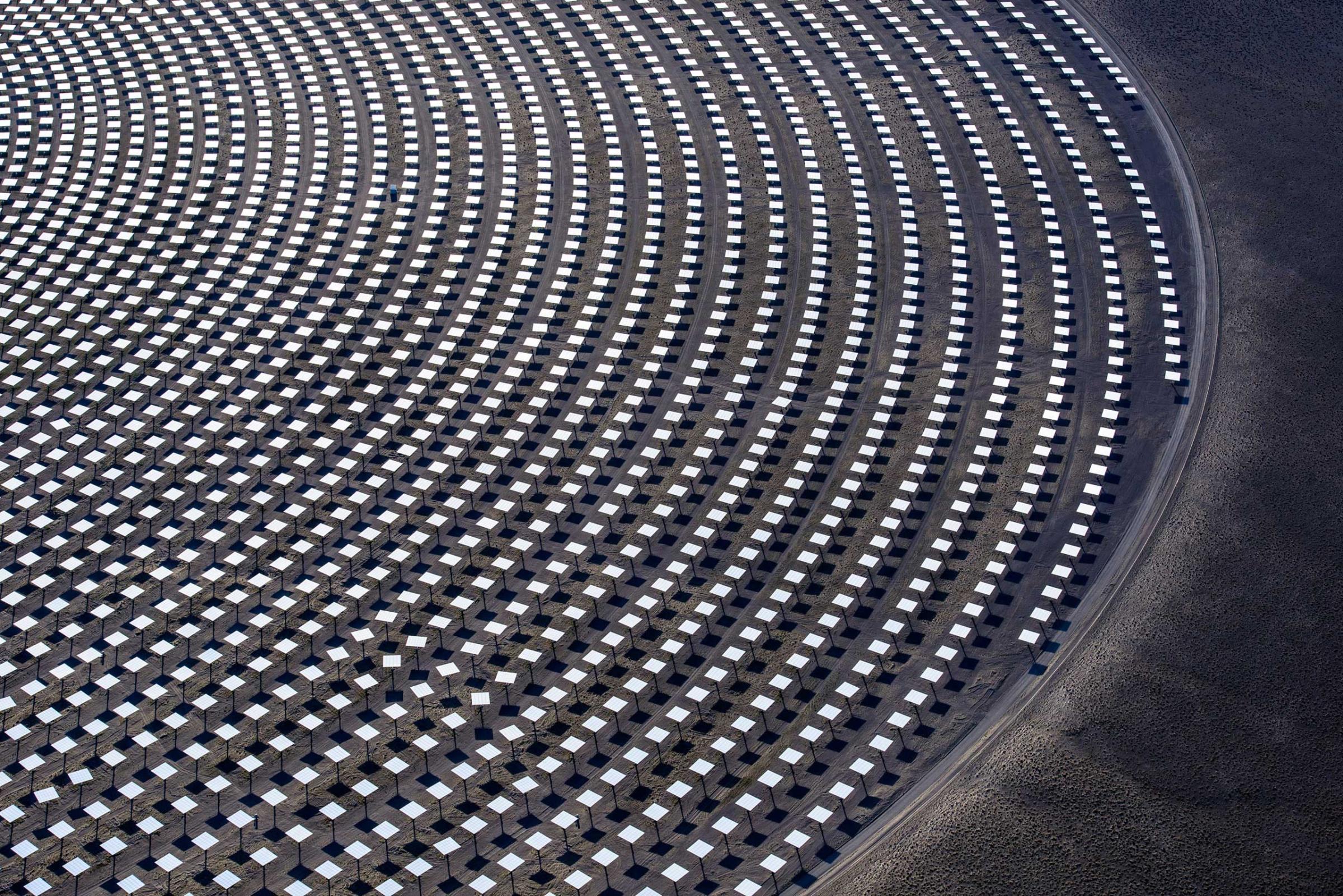

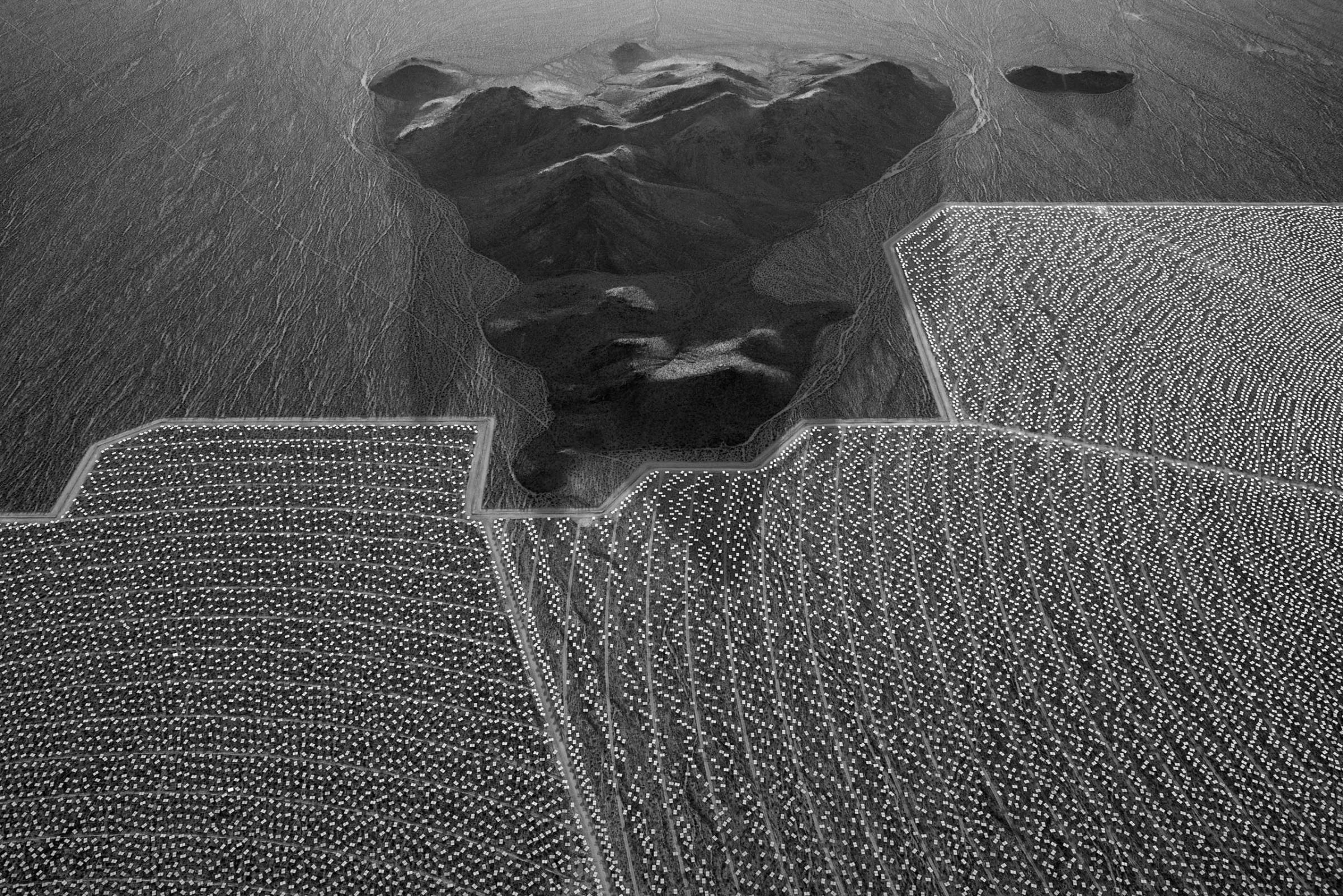

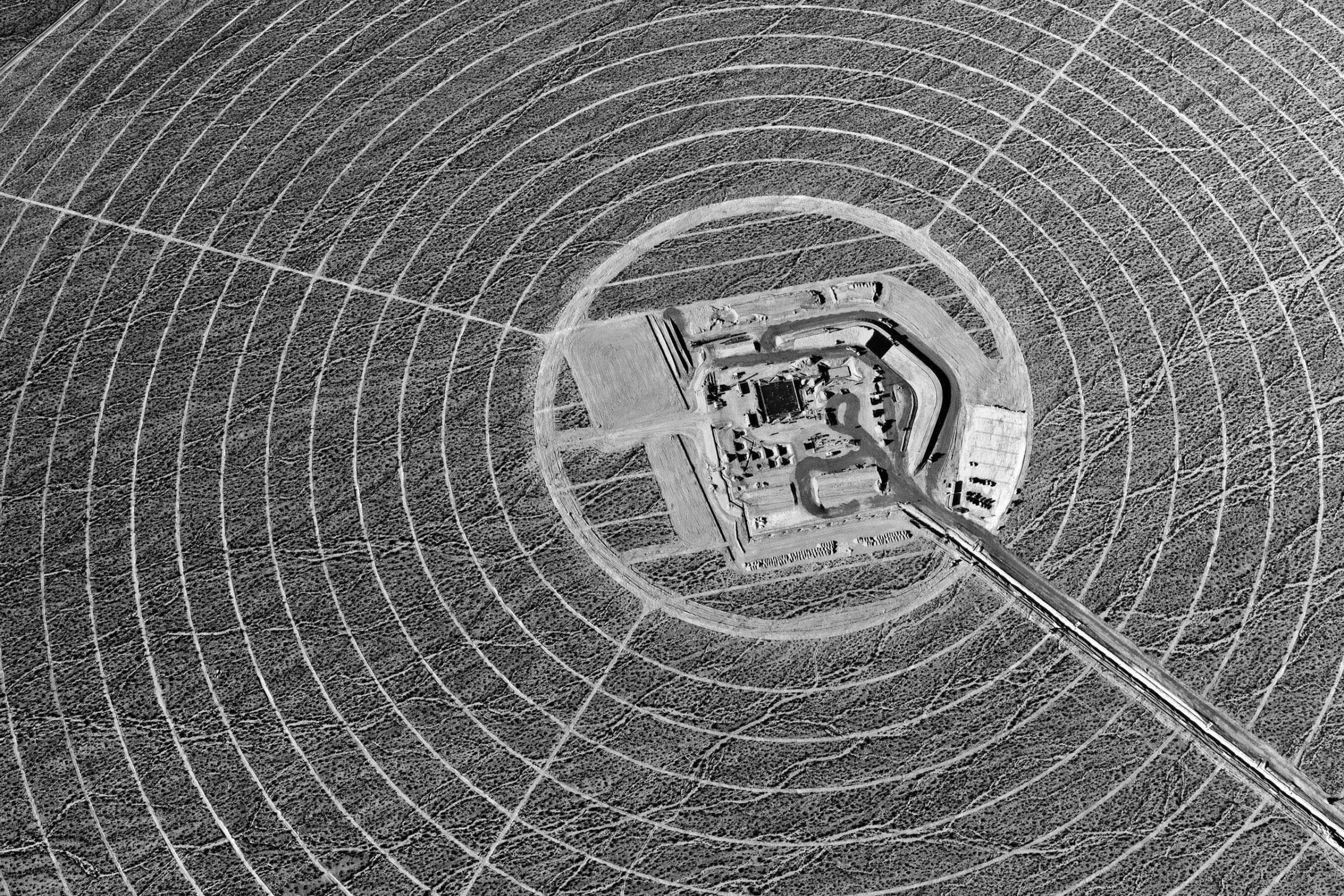

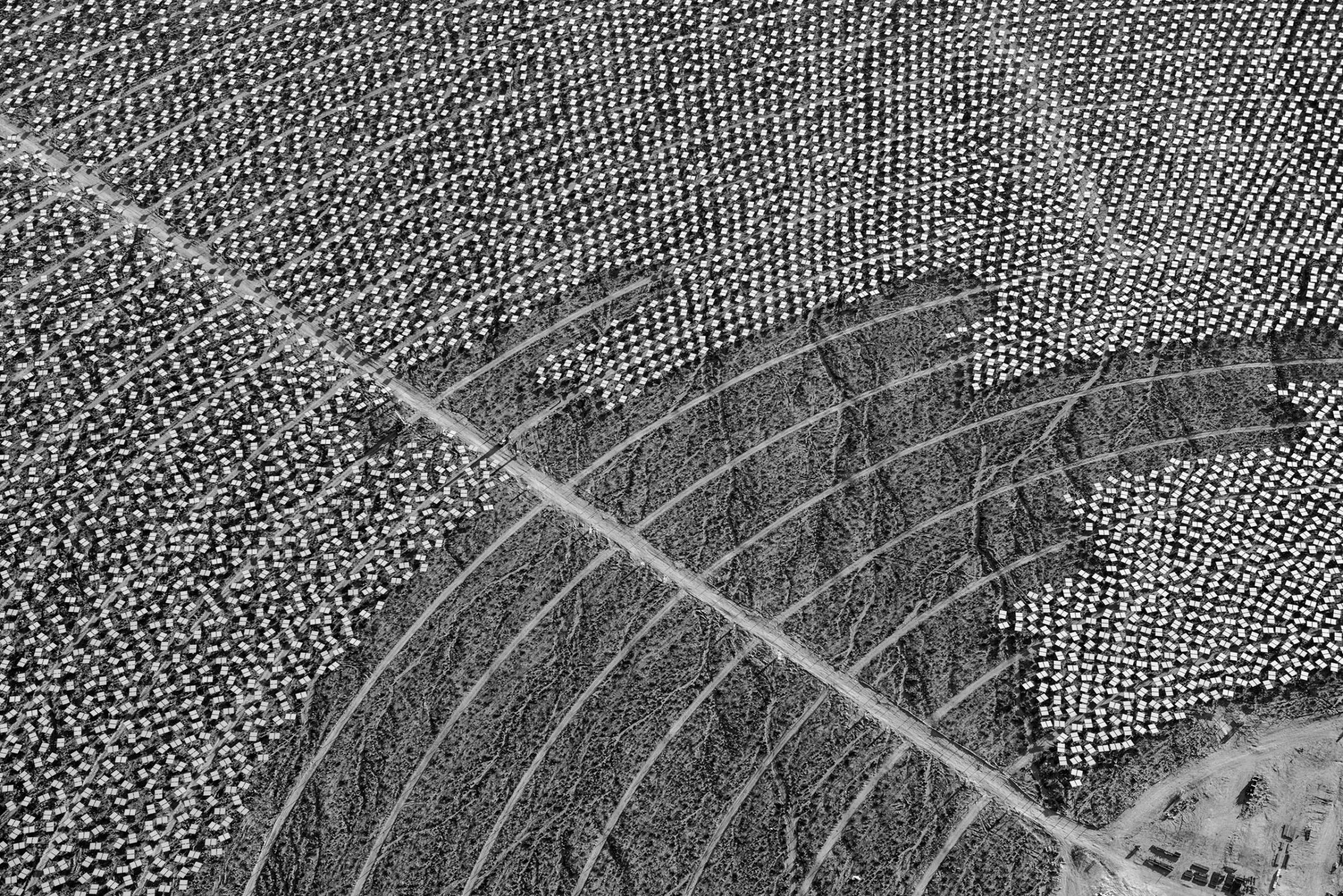

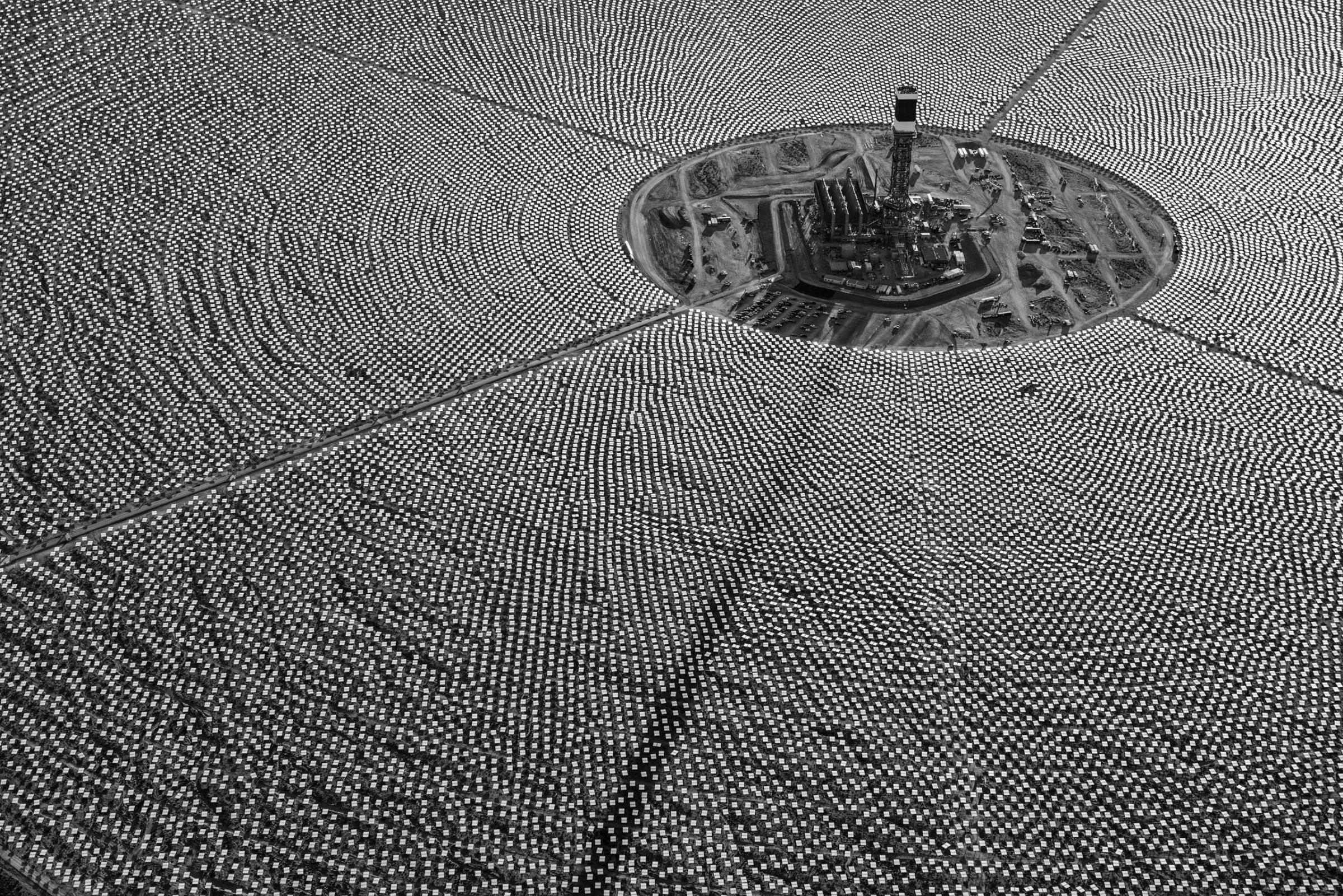

See the World's Largest Solar Plants From Above

Correction: An earlier version of this story misstated the tax credit solar lessees receive. Solar lessees do not receive any tax credits directly.

More Must-Reads from TIME

- Cybersecurity Experts Are Sounding the Alarm on DOGE

- Meet the 2025 Women of the Year

- The Harsh Truth About Disability Inclusion

- Why Do More Young Adults Have Cancer?

- Colman Domingo Leads With Radical Love

- How to Get Better at Doing Things Alone

- Michelle Zauner Stares Down the Darkness

Contact us at letters@time.com