It’s tough to top the historical amnesia that has let the Confederate flag fly over the South Carolina capitol for more than half a century. But the U.S. Army certainly can give Columbia’s banner a run for its money: it operates posts named for nine Confederate generals and a colonel, including the head of its army, the reputed Georgia chief of the Ku Klux Klan and the commander whose troops fired the first shots of the Civil War.

It shouldn’t be surprising. Both the Army and the South are tradition-bound entities that revere their past. Each of the posts was named for a Confederate officer long after the Civil War, including many in the first half of the 20th Century when the U.S. military was rushing to open training posts for both world wars. Army Colonel Steve Warren, a Pentagon spokesman, said Wednesday there is “no discussion” underway about renaming the posts.

The Army itself stood firm. “Every Army installation is named for a soldier who holds a place in our military history,” Brigadier General Malcolm Frost, the service’s top spokesman, said Wednesday. “Accordingly, these historic names represent individuals, not causes or ideologies. It should be noted that the naming occurred in the spirit of reconciliation, not division.”

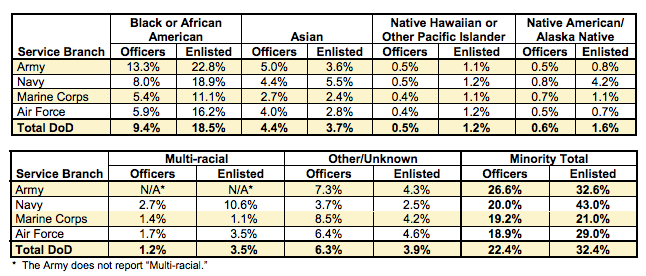

What makes all this especially bizarre is that the Army has always been the service with the most African-American troops. More than one of every five soldiers is black, double the Marines’ enlisted share. Every day, thousands of them salute smartly, preparing to defend the nation on soil honoring their race’s oppressors.

Don’t blame us, the Army seems to say. While the service traditionally solicited possible names from within its ranks, “unsolicited suggestions for names were also submitted from sources outside the military establishment, and political pressure and public opinion often influenced the naming decision,” the Army says in its history of naming Army installations. “As a result, it was common for camps and forts to be named after local features or veterans with a regional connection. In the southern states they were frequently named after celebrated Confederate soldiers.”

No kidding. All 10 of the bases are located in the Confederacy, stretching from Virginia to Texas. And some of the honored officers, frankly, don’t appear to deserve celebration:

Camp Beauregard, La., honors Louisiana native and Confederate General Pierre Gustave Toutant Beauregard (1818-1893, West Point class of 1838). It is a major training site for the Louisiana National Guard. Beauregard was the first brigadier general in the Confederate army. Dispatched to defend Charleston, S.C., his troops began shelling Fort Sumter on April 12, 1861, launching the Civil War.

Fort Benning, Ga., honors Brigadier General Henry Benning (1814-1875), a Georgia lawyer, politician, judge and supporter of slavery. The Army established Camp Benning, known as the Home of the Infantry, in 1918; it became a fort four years later 1950 (forts generally are bigger, more permanent installations than camps). “In the wake of Lincoln’s election, Benning became one of Georgia’s most vocal proponents of secession,” according to the New Georgia Encyclopedia. “On November 19, 1860, he delivered a speech before the state legislature urging immediate secession, ending the speech by saying,`[L]et us do our duty; and what is our duty? I say, men of Georgia, let us lift up our voices and shout, “Ho! for independence!” Let us follow the example of our ancestors, and prove ourselves worthy sons of worthy sires!’”

Fort Bragg, N.C., honors General Braxton Bragg (1817-1876, West Point class of 1837). He waged war ploddingly with frontal assaults, and a lack of post-battle follow-through that turned battlefield successes into post-battle disappointments. “Even Bragg’s staunchest supporters admonished him for his quick temper, general irritability, and tendency to wound innocent men with barbs thrown during his frequent fits of anger,” historian Peter Cozzens has written. “His reluctance to praise or flatter was exceeded, we are told, only by the tenacity with which, once formed, he clung to an adverse impression of a subordinate. For such officers—and they were many in the Army of the Mississippi—Bragg’s removal or their transfer were the only alternatives to an unbearable existence.”

Fort Gordon, Ga., honors Lieut. General John Brown Gordon (1832-1904), one of Lee’s most-trusted officers. The post began as Camp Gordon in 1917; it became Fort Gordon in 1956. It is home to the Army Signal Corps and the service’s Cyber Center of Excellence. “Generally acknowledged as the head of the Ku Klux Klan in Georgia, he was elected to the U.S. Senate in 1872,” according to the New Georgia Encyclopedia (Gordon denied the charge). “By the time of his death in 1904, Gordon had capitalized on his war record to such an extent that he had become for many Georgians, and southerners in general, the living embodiment of the Confederacy.”

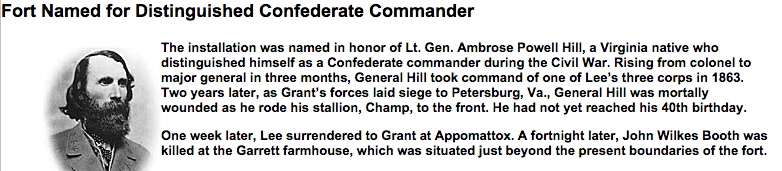

Fort A.P. Hill, Va., honors Virginia native Lieut. General A.P. Hill (1825-1865, West Point class of 1847). The Army created the post six months before the Japanese bombed Pearl Harbor in 1941. Today it is a training and maneuver center focused on providing realistic joint and combined-arms training. Hill had a frail physique and was frequently ill, attributes some historians believe are linked to the gonorrhea he contracted while on furlough from West Point (an infection that forced him to repeat his third year). A Union soldier from Pennsylvania shot and killed Hill in Petersburg, Va., a week before the end of the Civil War.

Fort Hood, Texas, honors native Kentuckian General John Bell Hood (1831-1879, West Point class of 1853). The post began as Camp Hood in 1942, becoming a fort in 1950. It is the largest active duty armored post in the U.S. military. Hood was wounded at Gettysburg, losing the use of his left arm. Despite that, he led his troops in a massive assault during the Battle of Chickamauga, suffering wounds that led to the loss of his right leg.

Fort Lee, Va., honors Virginian General Robert E. Lee (1807-1870, West Point class of 1829), the South’s commanding officer by the Civil War’s end. The War Department created Camp Lee within weeks of declaring war on Germany in 1917. The Pentagon promoted it to Fort Lee in 1950. Just south of Richmond, the capital of the Confederacy, the post is home to the Army Quartermaster School. Lee was the Confederacy’s most renowned general, and his forces inflicted tens of thousands of casualties on Union soldiers’ at Antietam, Gettysburg and Manassas.

Fort Pickett, Va., honors Major General George Pickett (1825-1875, West Point class of 1846), a Virginia native. Pickett’s 1863 charge at Gettysburg has been called “the high-water mark of the Confederacy” before ending up a Union victory. The charge resulted in a rebel bloodbath. Pickett fled to Canada for a year after the war ended, fearing execution as a traitor. Camp Pickett was dedicated on July 3, 1942, at 3 p.m., 79 years to the day and hour of Pickett’s charge in Gettysburg. It became a fort in 1974 and now is a Virginia Army National Guard installation.

Fort Polk, La., honors Lieut. General Leonidas Polk (1806-1864, West Point class of 1827), an Episcopal bishop born in North Carolina. Established in 1941, the post is now home to the Army’s Joint Readiness Training Center, which trains thousands of soldiers annually for overseas deployments. Polk fought bitterly during the Civil War with his immediate superior, General Braxton Bragg, of Fort Bragg fame. Before being killed in action in 1864 during the Atlanta campaign, Polk committed one of the biggest blunders of the war. He sent troops to occupy Columbus, Ky., which led the Kentucky legislature to appeal to Washington for help, ending the state’s brief try at neutrality.

Fort Rucker, Alabama, honors Tennessee native Colonel Edmund Rucker (1835-1924) who was often called “general” but never attained the rank (he was known as “general” after becoming a leading Birmingham, Ala., industrialist after the Civil War). Known today as the Home of Army Aviation, Fort Rucker was originally the Ozark Triangular Division Camp before being renamed Camp Rucker in 1942. It became Fort Rucker in 1955.

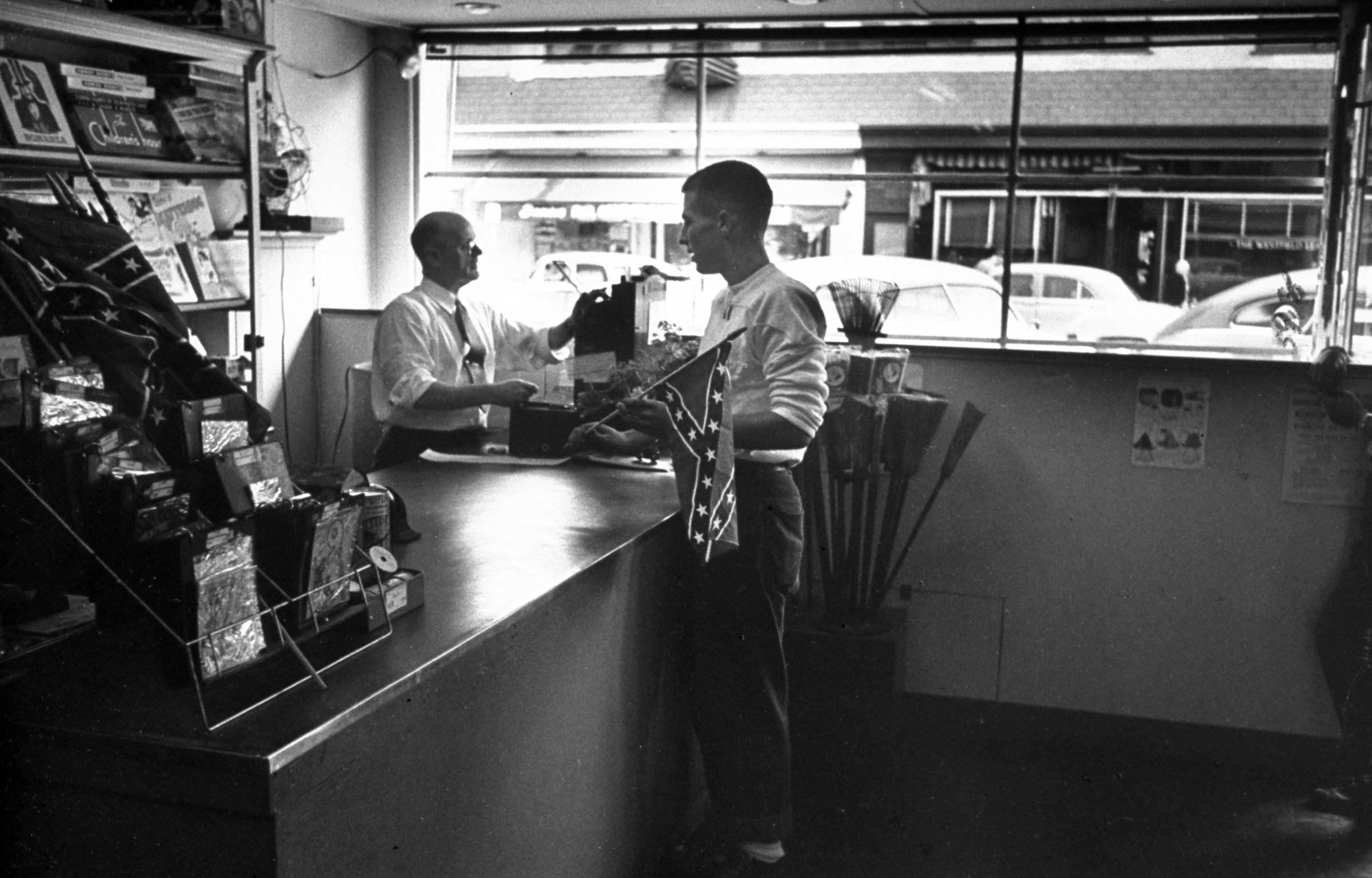

When the Confederate Flag Seemed Like a Fad

More Must-Reads from TIME

- Cybersecurity Experts Are Sounding the Alarm on DOGE

- Meet the 2025 Women of the Year

- The Harsh Truth About Disability Inclusion

- Why Do More Young Adults Have Cancer?

- Colman Domingo Leads With Radical Love

- How to Get Better at Doing Things Alone

- Michelle Zauner Stares Down the Darkness

Contact us at letters@time.com