Former Mississippi Governor and supporter of the White Citizens’ Council Haley Barbour recently assured us in no unclear terms that he was not offended by the Confederate flag, nor its place in the upper lefthand corner of the state flag of Mississippi. Barbour did not offer his perspective on whether or not the flag should remain standing at state capitols, but did suggest that the people of Mississippi should be the one to decide its flag’s fate. I agree with Barbour that this is a conversation Mississippians must have — but the opinions of white Mississippians for whom the racism the flag represents has negligible or zero effect should not take precedence. Whether or not Barbour finds the Confederate flag offensive, it is an inescapable symbol of white subjugation of black Americans.

In elementary school they taught us to salute the flag of Mississippi. It is almost like pledging allegiance to the American flag, but weightier, more intimate; it comes with an investment of your personal faith. With pride in Mississippi’s history and achievements, my eight-year-old self was urged to look with confidence toward the state’s future, and I was cool with that — until they tried to make my mama do it, too, at a school assembly. She kept her seat, and yanked me down. So did all of the other black parents to their black kids in attendance. This made it so that only half of the gymnasium in which the assembly was held stood to salute the flag of Mississippi, and the sovereign state for which it stands.

There is more than one way to teach gravity to a second grader.

Without knowing what a saltire was and without knowing what the Confederacy was, I knew what a nigger was, and that I was one. This is the way that Mississippi makes youthfulness a farce. Children are born into the rigidity of the systems that keep us so orderly, in ways that a stranger from a heathen state might mistake for good behavior. This is especially true for black children, who are threatened with things like whippings with tree branches or a call to the police when we misbehave, who are taught to be especially good around the parents of white friends, who might punish each other for bad grammar.

To be black and young and conscious in the state of Mississippi is to sit daily in the sauna of honeysuckle-scented air with a weariness you’ve more or less felt since you were in a stroller, and way before. You’ve weathered the centuries of racism that have molded your environment, and you perspire in the hottest heat of social injustice, and of the subtropical climate, and you dare to love it here. You have to. You agree with James Meredith, that Mississippi is yours, and that one must love what is his. More than that, you have to accept that it is yours, and that you have the right to love it, and thus hold it accountable. You have to affirm your place within it, no matter how much weeping and moaning and teeth-gnashing is required, because otherwise you would have nothing, and you have every right to having your existence honored in the place you have no choice but to call your home.

What white racist Southerners don’t realize is that black people exist as more than barriers to meaningful engagement with the world around them. They forget that the South belongs to black people, too, and that our ancestors matter as much as yours; that the pride that they assign to the Confederacy is not more valid, more worthy of remembrance, than the shame and the evil inflicted upon those black ancestors whose enslavement and blood gave marble and brick and wealth to the fantasy of the Old South.

Because blackness is the South, in foundation, and in future. And blackness can no longer be an inconvenient sidebar to the carefully whitewashed perception of the South. Mississippi Senator and Tea Party supporter Chris McDaniel claimed that the arguments for removing the flag are steeped in political correctness; that the massacre in South Carolina should not be used to “promote a political agenda.” What McDaniel and others fail to realize is that the Confederate flag in itself promotes a political agenda: one of racism and black oppression, one with which Dylann Roof sympathized, and one that he wielded in order to cause the deaths of nine innocent people, solely because they were black.

To object to the symbolism that so long has stood in silent accordance with the erasure of blackness is not about political correctness or hurt feelings; it is about enabling continued violence against black people in a country that has failed to protect us.

But we are here. This place is ours, too.

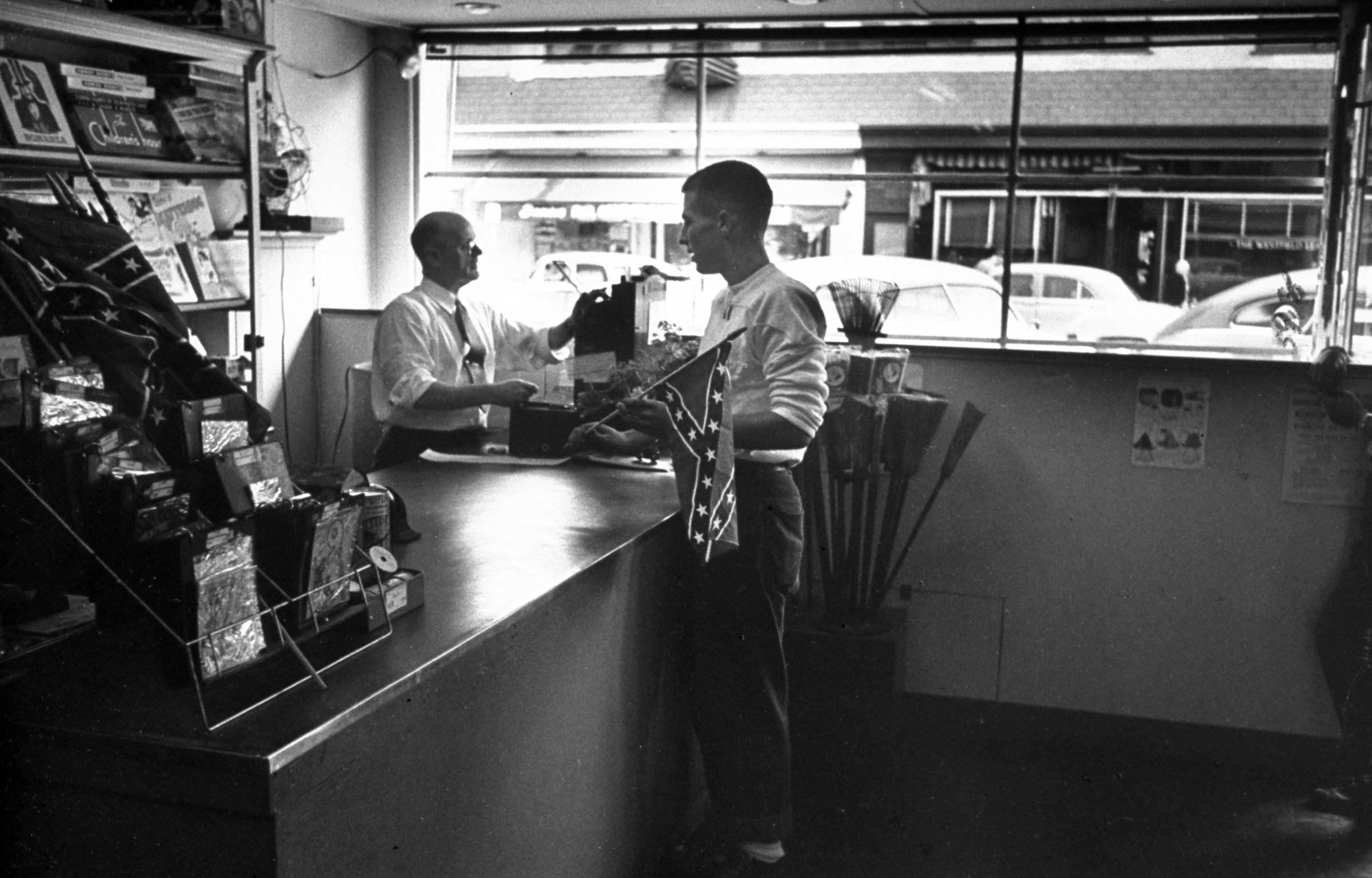

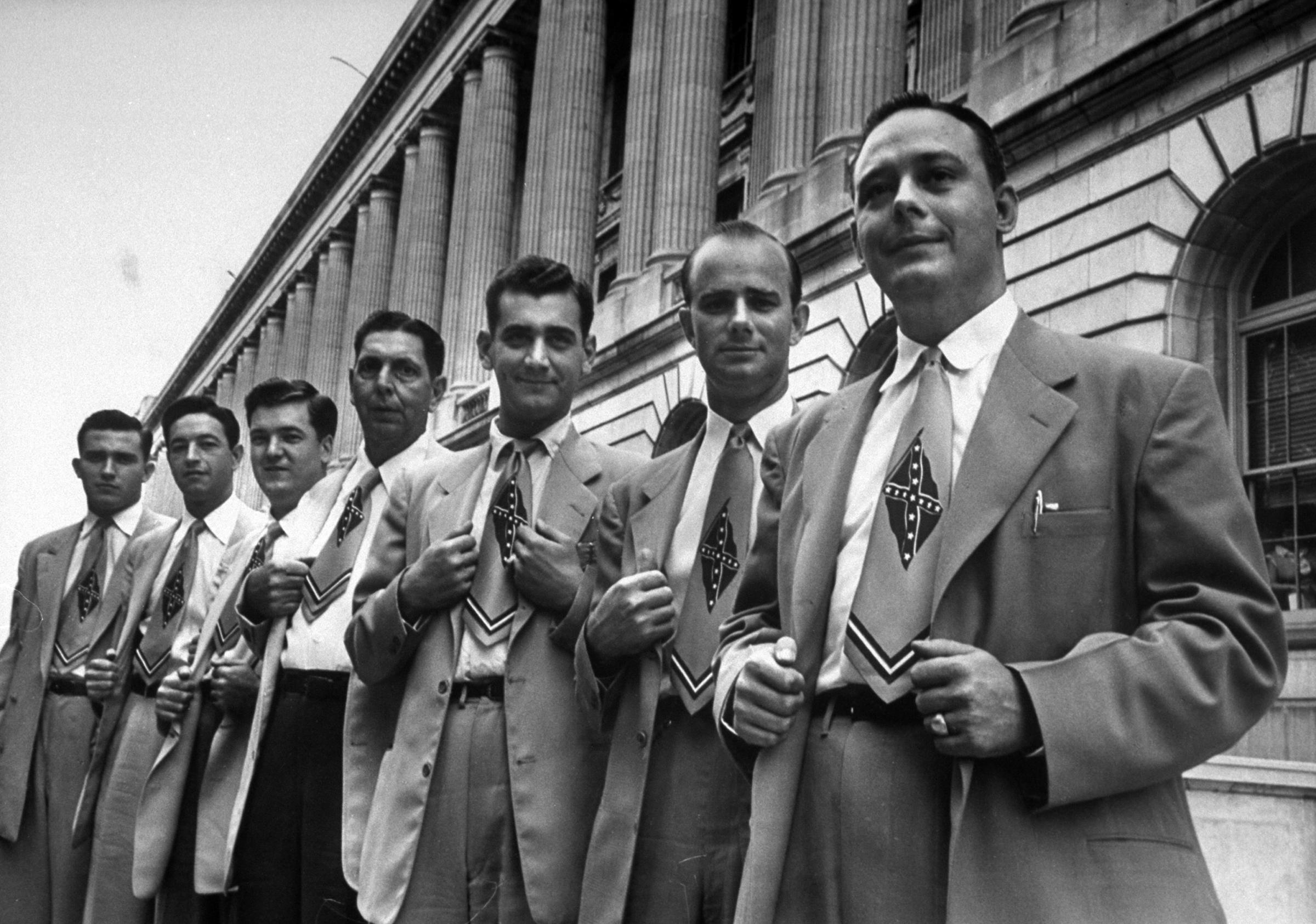

When the Confederate Flag Seemed Like a Fad

More Must-Reads from TIME

- Cybersecurity Experts Are Sounding the Alarm on DOGE

- Meet the 2025 Women of the Year

- The Harsh Truth About Disability Inclusion

- Why Do More Young Adults Have Cancer?

- Colman Domingo Leads With Radical Love

- How to Get Better at Doing Things Alone

- Michelle Zauner Stares Down the Darkness

Contact us at letters@time.com