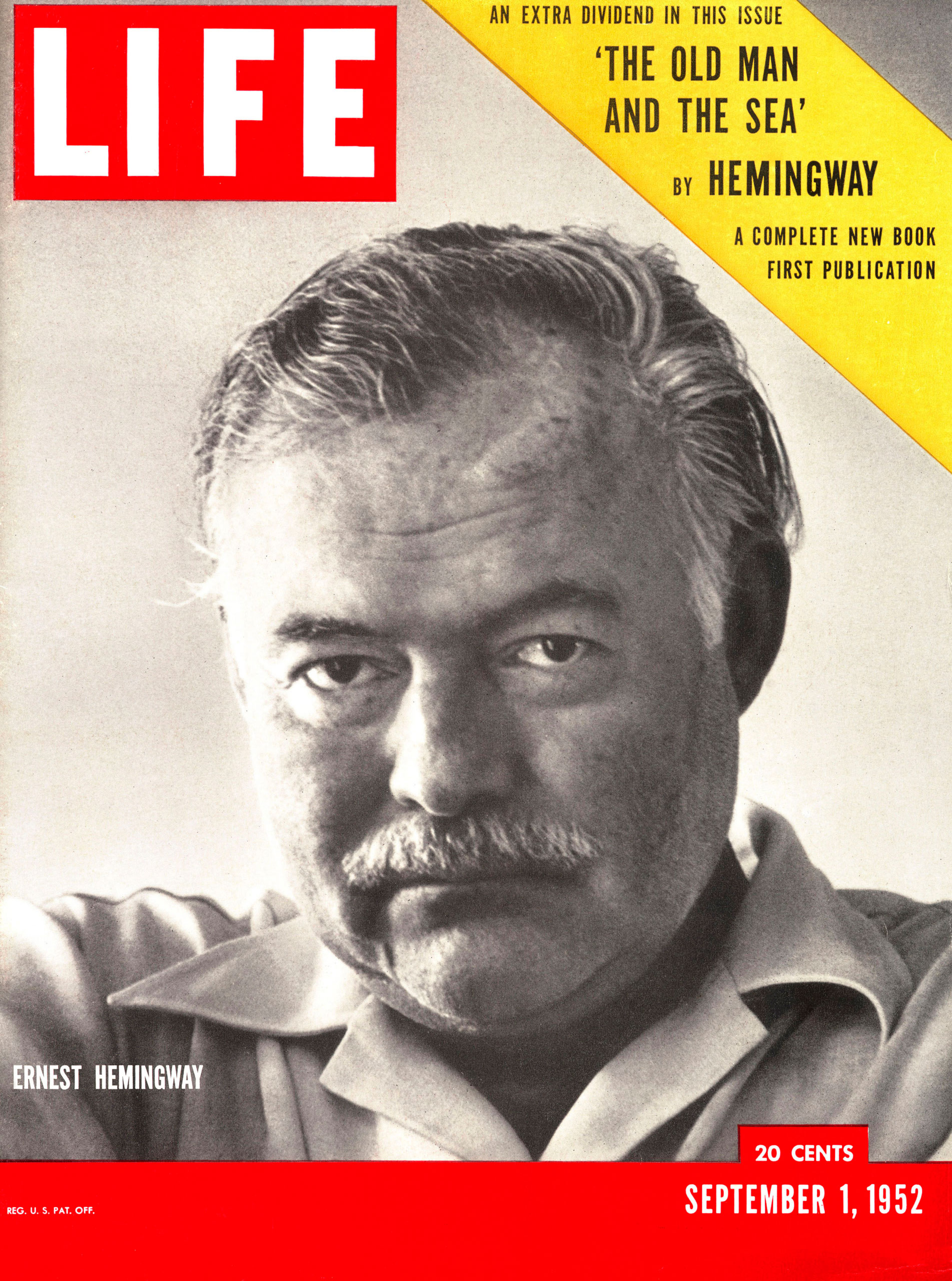

The festival of San Fermin has been held in Pamplona, Spain, for centuries and the annual event is still the area’s claim to fame. Of the many components of the days-long event, which begins on Monday this year, the running of the bulls (which starts Tuesday) is the most famous part—and, thanks to Ernest Hemingway’s The Sun Also Rises, the early 20th century is perhaps its most famous era.

The novel concerns—as TIME phrased it in the original 1926 book review—the”semi-humorous love tragedy of an insatiable young English War widow and an unmanned U. S. soldier” and takes place in “prizefights, bars, bedrooms, [and] bullrings in France and Spain.”

In 1932, TIME covered the running (or, rather, “driving”) of the bulls. Though the magazine didn’t employ Hemingway’s terse declarations or calculated repetition, it painted a picture of the world that inspired the author’s story:

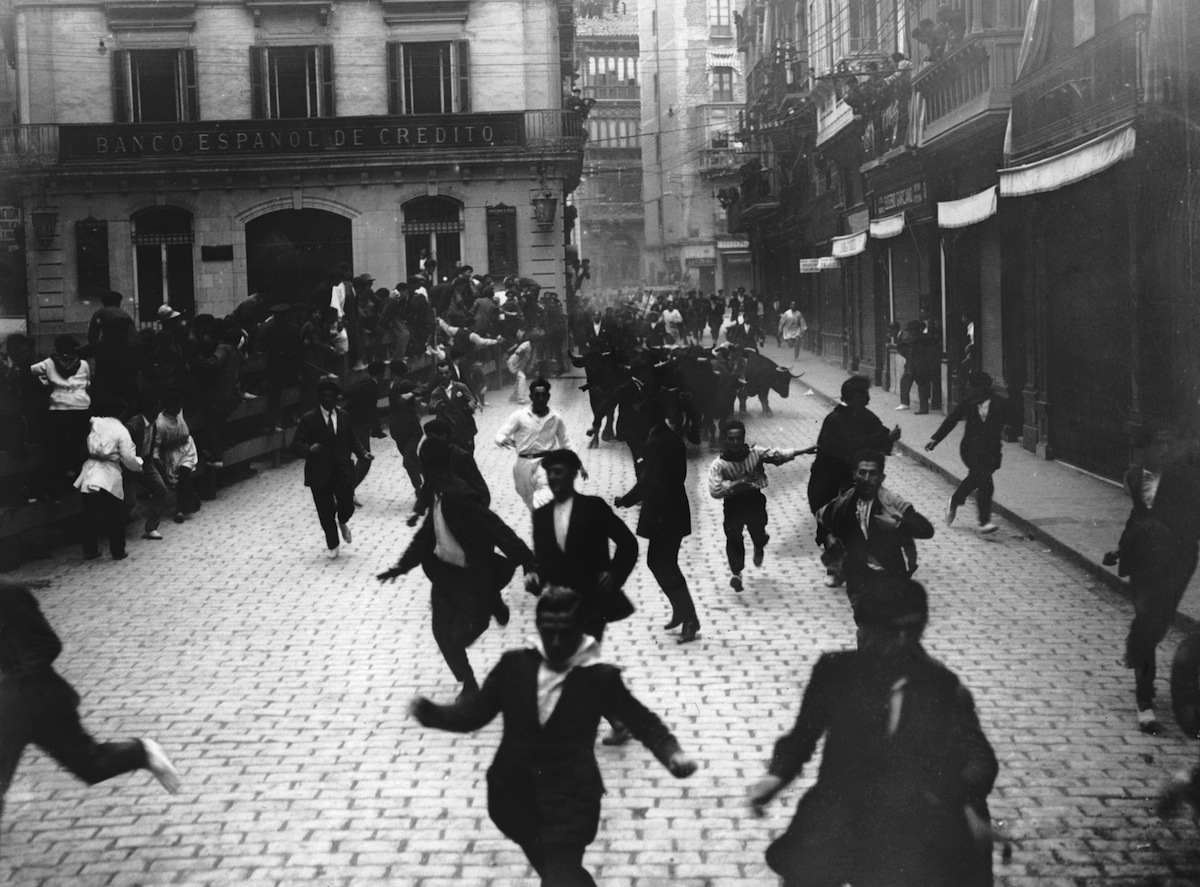

For 51 weeks of the year the capital of Navarra is a sleepy little Spanish city where half-naked children play in the narrow streets and café waiters doze under the arcades of the broad, quiet Plaza de la Constitucíon. But in the second week of July, Pamplona becomes bull-mad, its streets and plaza are full of snuffing, rushing bulls. Hotels and rooming houses overflow with visitors from Madrid, Bilbao, San Sebastian, with tourists from St. Jean-de-Luz, Biarritz and Paris. Peasants from miles around sleep in wagons, in the fields, or do not sleep at all. For four days from 6 a. m. until long after midnight sleep is next to impossible while Pamplona celebrates the Fiesta of San Fermín, its patron saint. There are bullfights, street dancing, parades of huge grotesque figures, much drinking of strong Spanish wine. But by far the most exciting ceremony—one which takes place only at Pamplona—is the encierro (driving of the bulls).

Soon after dawn the first day of the fiesta this week, hundreds of youths gathered at the edge of town near the railroad station. Men climbed upon six big cages, reached down and opened them. Out walked six bulls, blinking in the sunlight. They were strong, lithe, handsome, each branded with the mark of Don Ernesto Blanco. They looked around, uncertain what to do, until from the crowd of youths came a yell: “Hah! Hah! . . . Toro!” The bulls lowered their heads, charged the crowd. The crowd took to its heels, the bulls stampeding in pursuit.

Read the full story, here in the TIME Vault: Pamplona’s Encierros

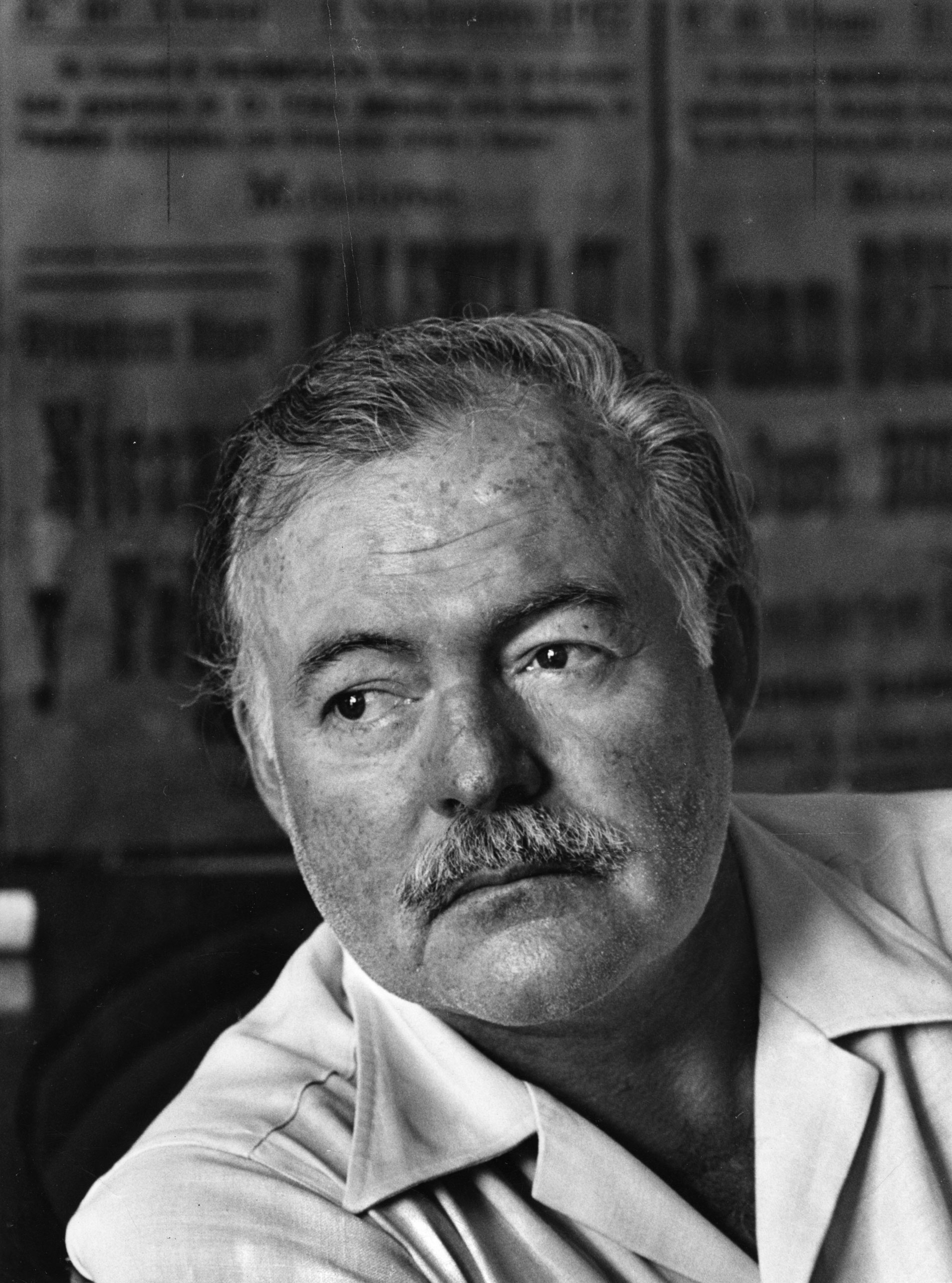

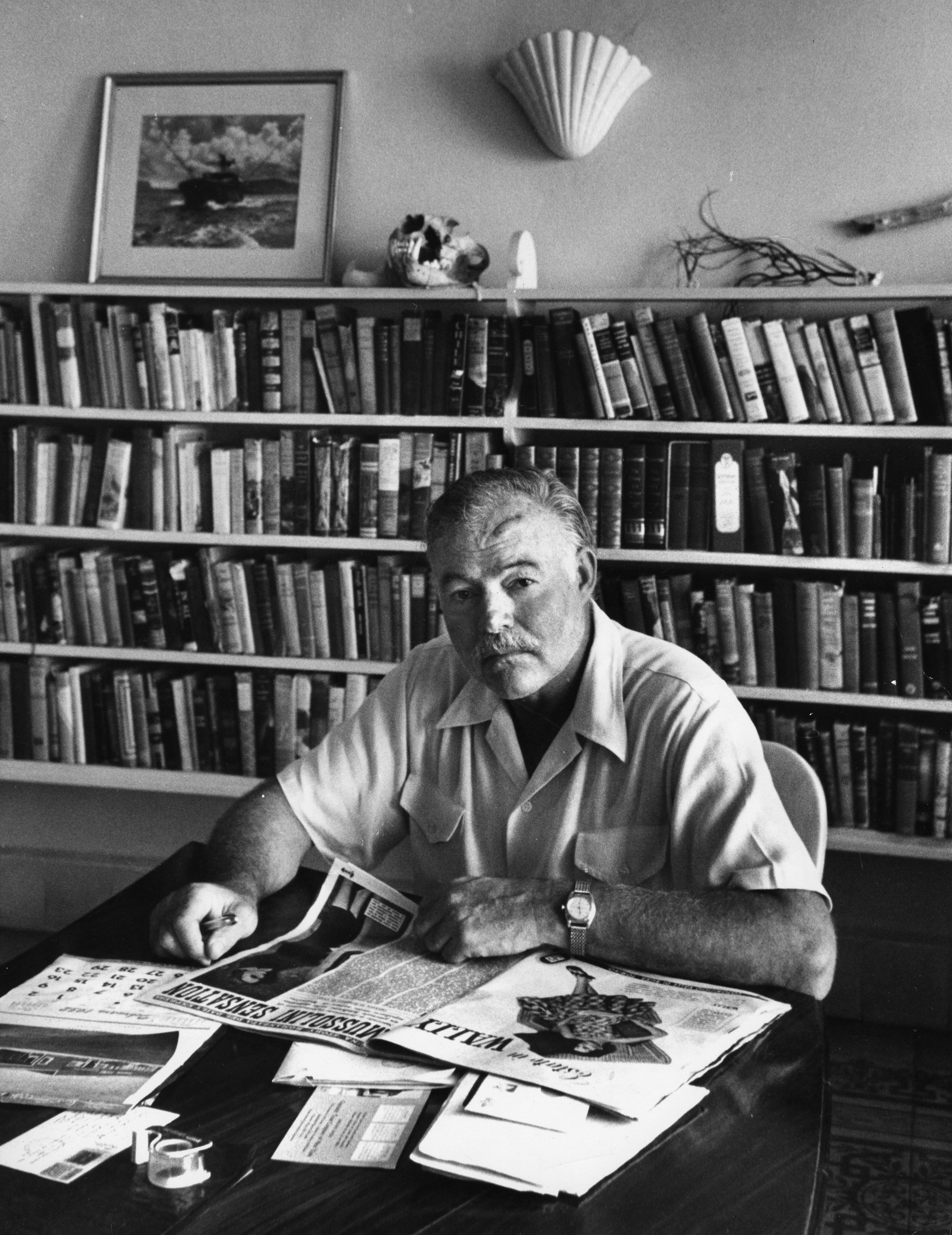

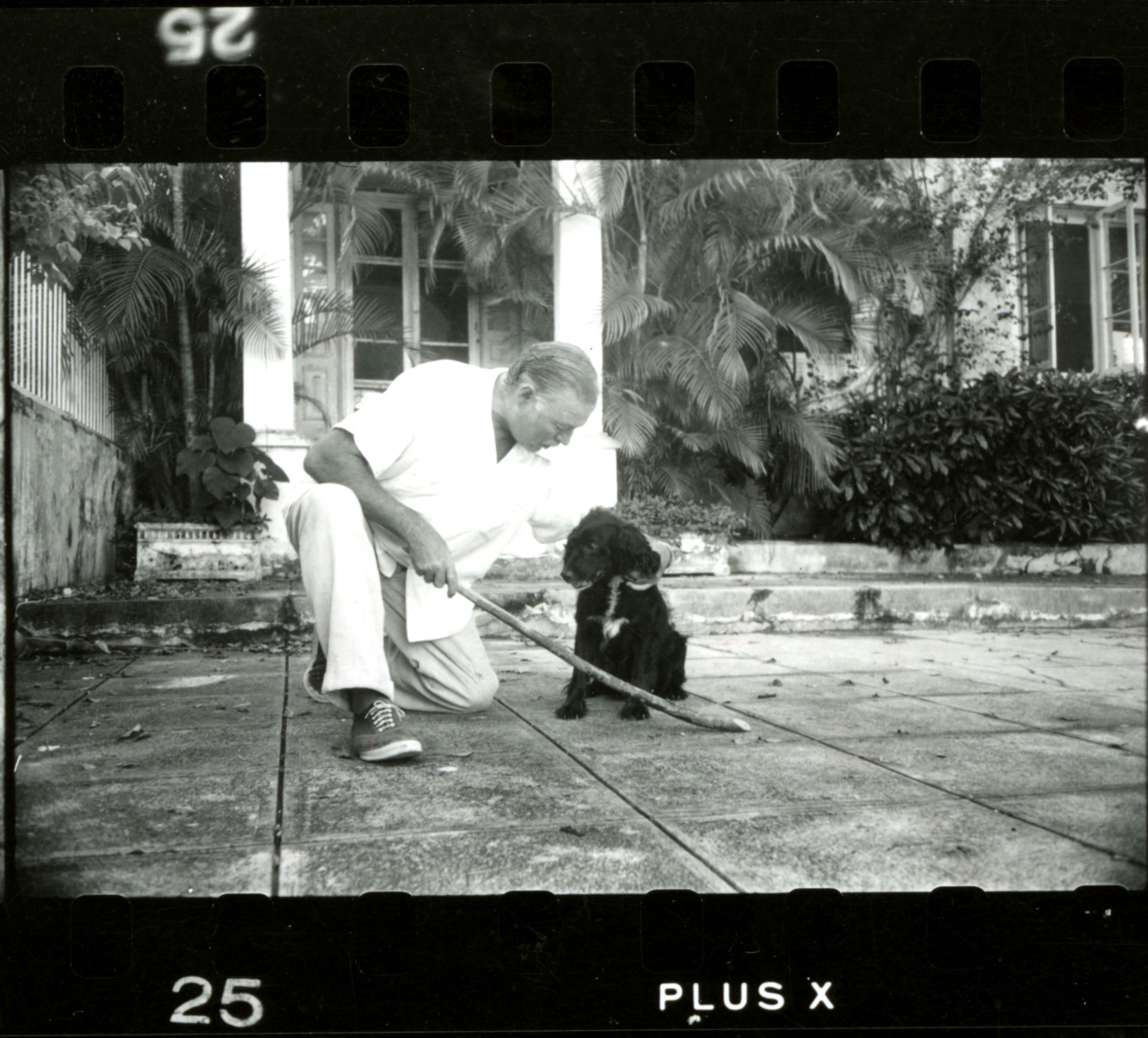

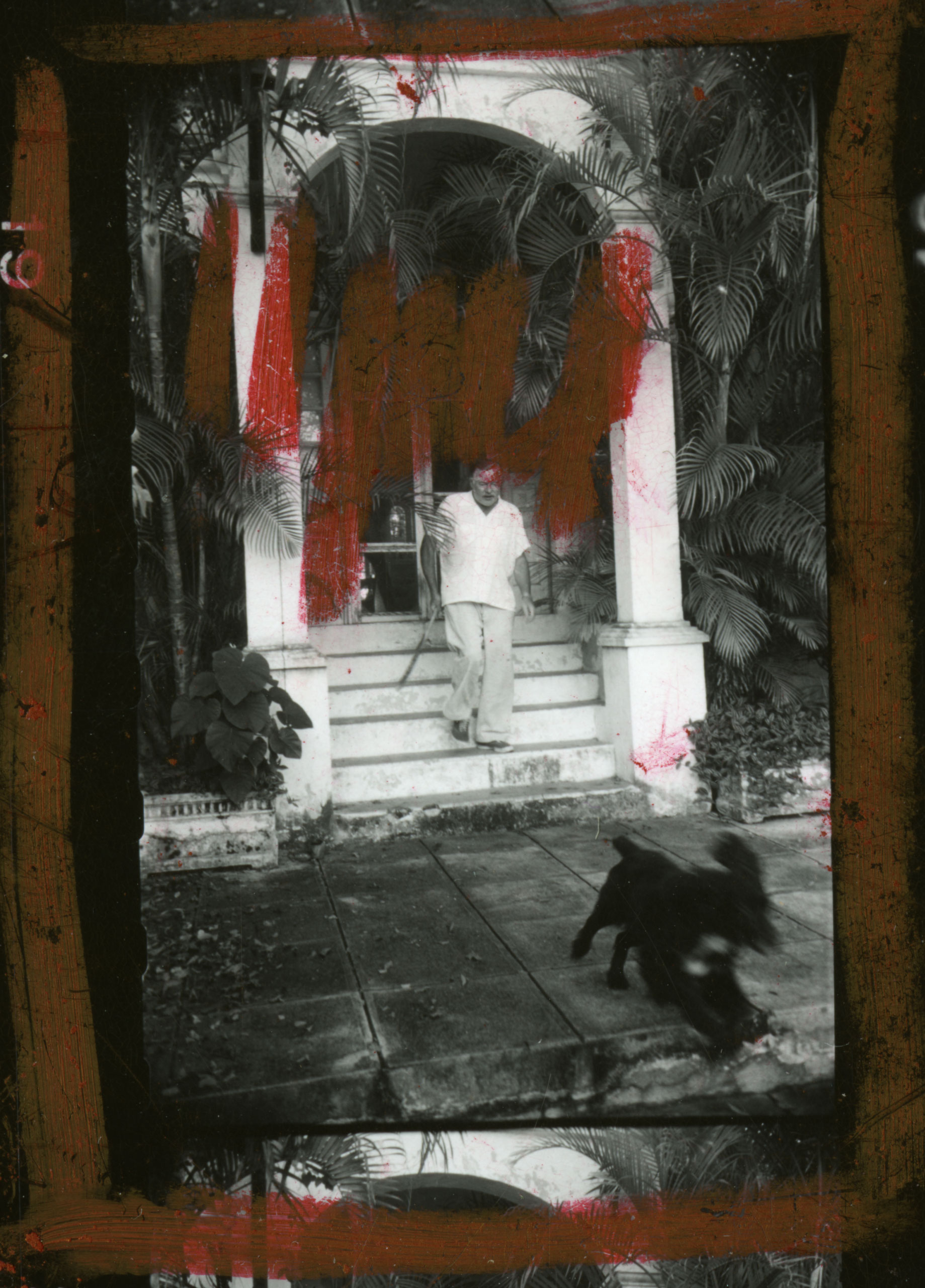

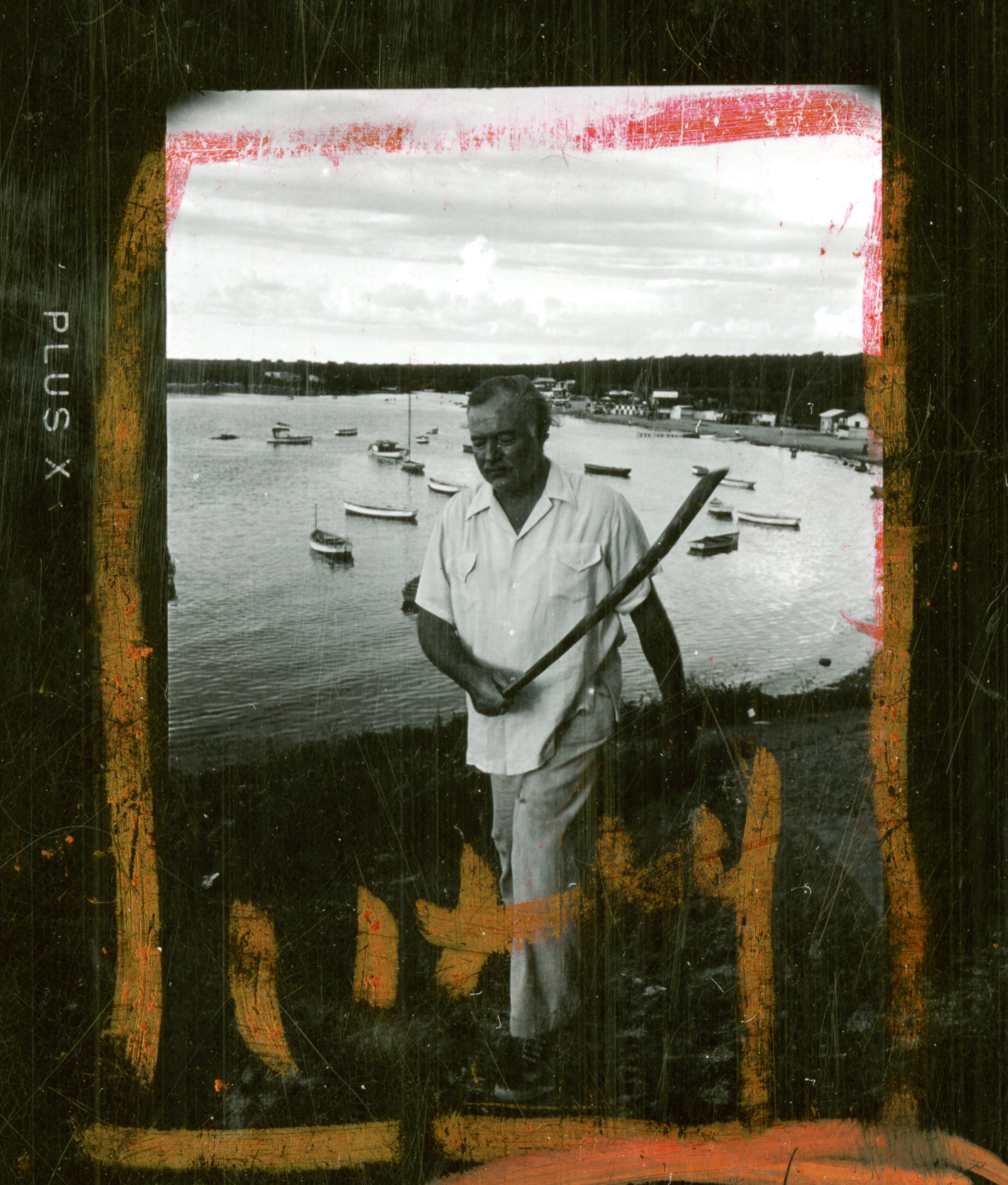

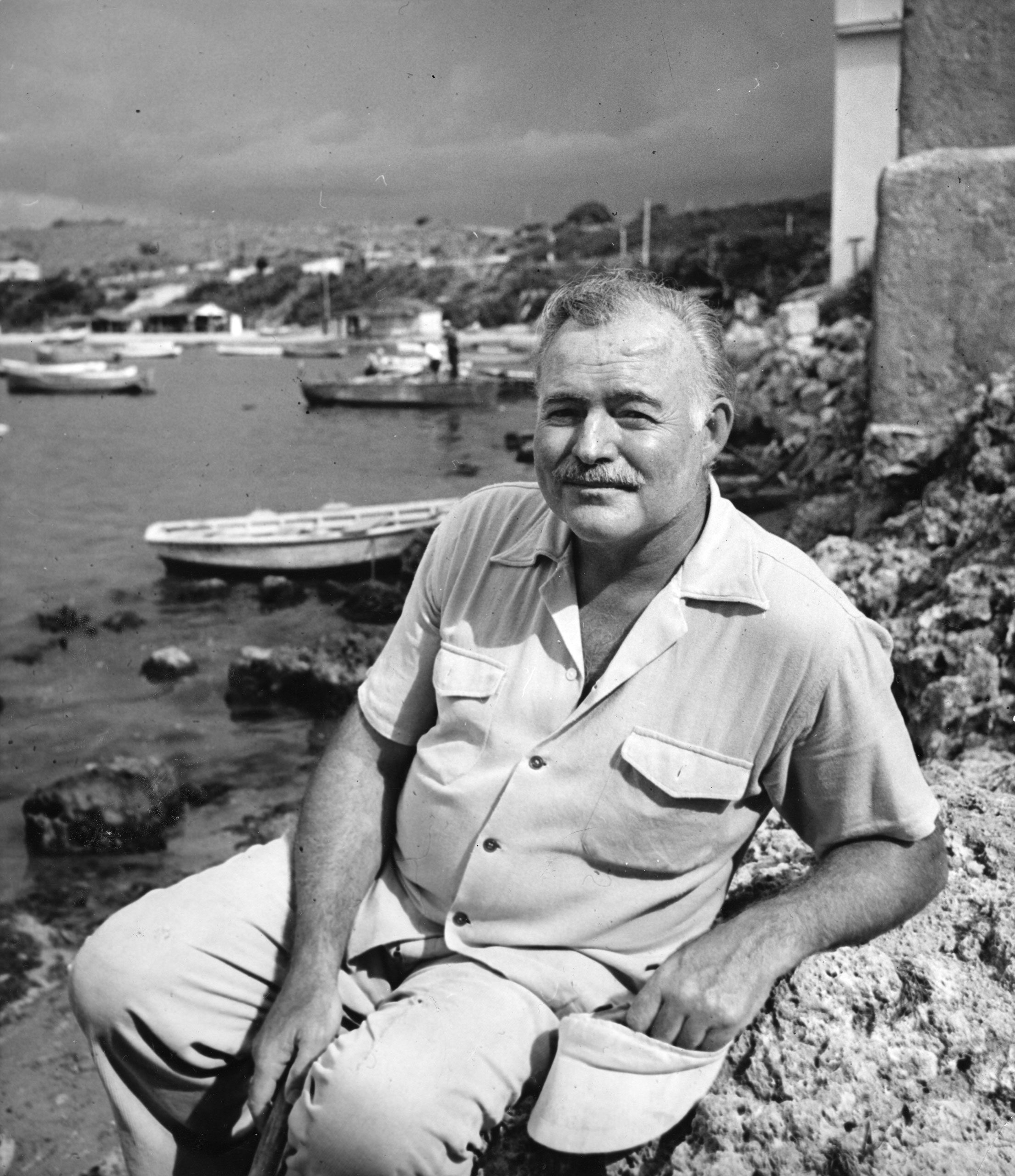

Hemingway in Cuba, 1952: Portrait of a Legend in Decline

More Must-Reads from TIME

- Cybersecurity Experts Are Sounding the Alarm on DOGE

- Meet the 2025 Women of the Year

- The Harsh Truth About Disability Inclusion

- Why Do More Young Adults Have Cancer?

- Colman Domingo Leads With Radical Love

- How to Get Better at Doing Things Alone

- Michelle Zauner Stares Down the Darkness

Write to Lily Rothman at lily.rothman@time.com