Think of the Civil Rights Movement, and you’re unlikely to think of Charleston, S.C. We think of Montgomery, Ala., home of Rosa Parks. We think of Mississippi for the tragic killing of Medgar Evers, Birmingham for the horrendous murder of four little girls in the bombing of the 16th Street Baptist Church, Selma for the brutal beating of hundreds of voting rights advocates as they marched across the Edmund Pettus Bridge.

But Charleston—the city where on Wednesday a man opened fire inside a historic black church, killing nine—indeed has a history rich in the fight for racial justice.

One may say the civil rights movement in Charleston started as early as 1862, when slave Robert Smalls led a revolt in which he and 12 others took over the steamboat they were working on during the Civil War and offered it to Union forces. He won his family’s freedom, became a state senator and served in the U.S. Congress for five years.

But despite his feel-good story, lynchings, Jim Crow and segregation ruled the land in post-Civil War Charleston. The city’s local NAACP branch was established in 1917. Its earliest battles were over education, as the branch fought to get black teachers hired in the school district. Educator Septima Poinsette Clark became one of the city’s leading civil rights activists fighting for equal pay for black teachers. She was fired in 1956 when the South Carolina state legislature passed a law ruling that state employees could not be members of the NAACP. Clark continued to work with the NAACP and eventually worked with the Southern Christian Leadership Conference, the organization co-founded by Rev. Martin Luther King Jr., to teach adult literacy and voting rights education in Citizenship Schools throughout the South. She became the first black woman elected to the Charleston School Board in 1975.

There was a rumbling throughout the country. African Americans were restless—they faced poor schools, few jobs and segregated facilities, and something had to give. In 1950, NAACP attorney and future U.S. Supreme Court justice Thurgood Marshall led a team of lawyers in filing a lawsuit against Clarendon County schools, challenging school segregation. Local Charleston service-station attendant Harry Briggs and his wife Eliza, a maid, were the first petitioners on the complaint. Though a three-judge panel upheld the school system’s segregation policy in Briggs v. Elliott, Judge Walter Warring dissented, writing that “segregation is per se inequality.” The Briggs case was combined with four other school desegregation cases in the historic 1954 Brown v. Board of Education case, in which the U.S. Supreme Court ruled separate but supposedly equal public schools unconstitutional.

But integration would be difficult. One of the main proponents of desegregation in Charleston was Rev. Joseph DeLaine, a minister and educator who fought to desegregate transportation and facilities as well as schools in Clarendon County. After the Brown ruling, his home and church were burned to the ground. The civil rights activist moved to another county but continued to receive death threats. DeLaine was forced to leave South Carolina altogether after firing back at night-riders who shot at his home, threatening his family.

Indeed, nearly a decade later Rev. Martin Luther King Jr. would visit Charleston during the height of the Civil Rights Movement. He spoke at the historic Emanuel AME Church in 1962. Inspired, the city’s black community boycotted segregated facilities, low wages and lack of employment opportunities in the summer of 1963. Their peaceful protest would be called the Charleston Movement, led by NAACP leader J. Arthur Brown and Rev. James Blake. The civil rights activists created a blacklist of stores, restaurants and theaters that did not serve or hire African Americans. One of the protestors, Harvey Gantt, helped lead a sit-in at Kress department store. Gantt became the first African American student to enroll in Clemson University that year and later served two terms as mayor of Charlotte, N.C.

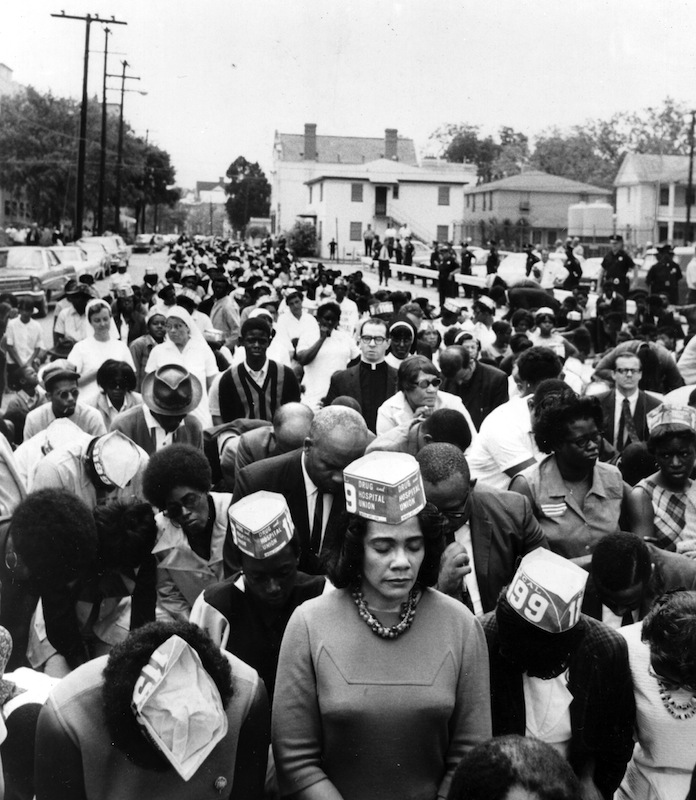

More than a thousand African American citizens went to jail during the Charleston Movement, but Kress and other stores eventually opened their doors to blacks at the end of the protest. In the fall of 1963, 11 students desegregated Charleston Public Schools. And it didn’t stop there: After her husband’s death, Coretta Scott King led a march for workers’ rights in the city of Charleston. As the world-changing decade came to a close, female workers of the Charleston Hospital went on strike in 1969 to protest poor working conditions and low wages.

Some cities rise to the top of discussions of the civil rights movement, just as the decade of the ‘60s does. But, just as a place like Charleston may have a less celebrated but still crucial place within that history, so has the story of the fight against racial inequality continued.

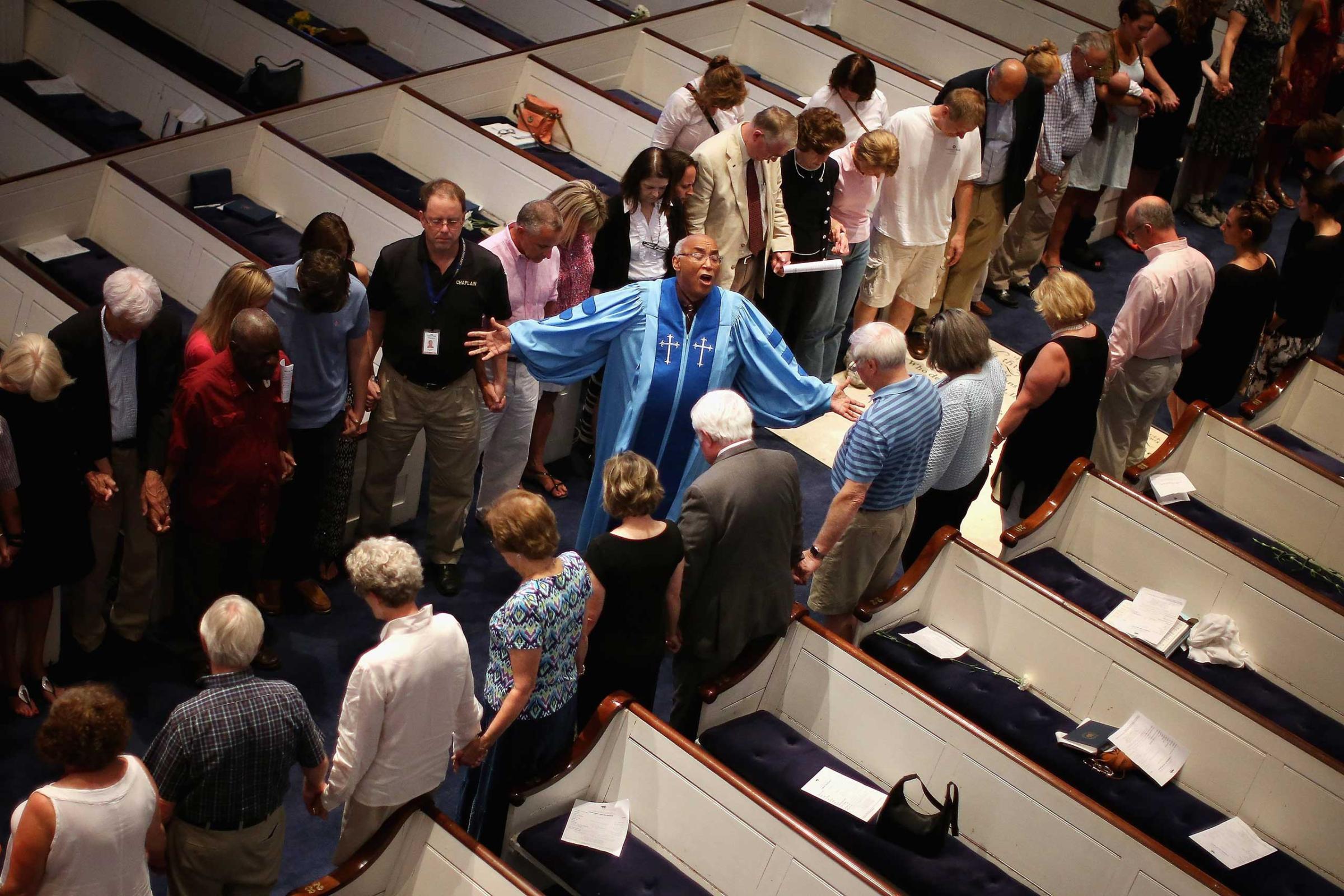

See Charleston Come Together to Mourn Church Shooting Victims

More Must-Reads from TIME

- Cybersecurity Experts Are Sounding the Alarm on DOGE

- Meet the 2025 Women of the Year

- The Harsh Truth About Disability Inclusion

- Why Do More Young Adults Have Cancer?

- Colman Domingo Leads With Radical Love

- How to Get Better at Doing Things Alone

- Michelle Zauner Stares Down the Darkness

Contact us at letters@time.com