It’s official: In five years, the $10 bill will have a woman on it. Some feminists may argue that announcing the gender instead of a specific woman smacks of tokenism, but faces on currency are primarily about symbolism, and recognizing female contributions to American history with a face on a bill seems like a feminist statement in the best sense of the word. Which woman will get the nod?

The dead white men who currently appear on our money were all presidents of the U.S. (except for Alexander Hamilton and Benjamin Franklin, who were Founding Fathers). Obviously, there are no women who meet that criteria, and while there are plenty of distinguished female politicians, any political selection—especially from the past century—is sure to stoke controversy. For instance, when House Minority Leader Nancy Pelosi suggested Secretary of Labor Frances Perkins, America’s first female cabinet member and New Deal architect, conservative columnist Debra J. Saunders was quick to point out that Perkins was “an educated white political Democrat just like Pelosi.”

If holding high political office is not a requirement—and it certainly isn’t in many other countries, which put scientists, writers and artists on their money—one can reach into a far larger pool of candidates who have played a major role in U.S. history. (Though presumably USA Today’s nomination of Oprah Winfrey, Beyoncé and Betty White is tongue-in-cheek.)

Since the new $10 will mark the 100th anniversary of the 19th Amendment, which gave women the right to vote, a suffragist leader would be a natural choice. Elizabeth Cady Stanton, the movement’s matriarch, was not only a formidable activist but an impressive political thinker, as evidenced by her 1892 speech to the Senate Judiciary Committee, “Solitude of Self.” What’s more, her arguments, which grounded the fight for women’s rights in the American tradition of individualism and self-sovereignty, should make her an appealing figure not only for feminists but for conservatives of a more libertarian stripe. (As principal author of the 1848 Seneca Falls “Declaration of Sentiments and Resolutions,” modeled on the Declaration of Independence, Stanton is also a direct intellectual heir to the Founding Fathers.)

Others have suggested the great African-American abolitionists Harriet Tubman (the winner of the online poll conducted by a recent campaign to put a woman on the $20 bill) and Sojourner Truth. The poll also included Perkins, First Lady Eleanor Roosevelt, first African-American congresswoman Shirley Chisholm, and feminist Betty Friedan.

But there are also more provocative choices. From the 19th Century, there’s America’s first female presidential candidate, Victoria Woodhull, a revolutionary and charismatic figure. She was a suffragist, newspaper publisher, charismatic speaker who advocated for free love, and the first woman to found and run a Wall Street brokerage firm. (Unfortunately for libertarians, she also published the first English version of Karl Marx’s Communist Manifesto.)

An even more unconventional choice in some ways would be 20th Century academic and diplomat Jeane Kirkpatrick, foreign policy advisor to Ronald Reagan, the first woman to serve as U.S. ambassador to the U.N., and author of the “Kirkpatrick Doctrine” which held that the U.S. should back anticommunist governments around the world. She was loathed by the left, which she accused of knee-jerk anti-Americanism, and she was, in turn, harshly criticized for advocating morally dicey alliances with authoritarian right-wing regimes. Be that as it may, she was a key player on the winning team in the Cold War.

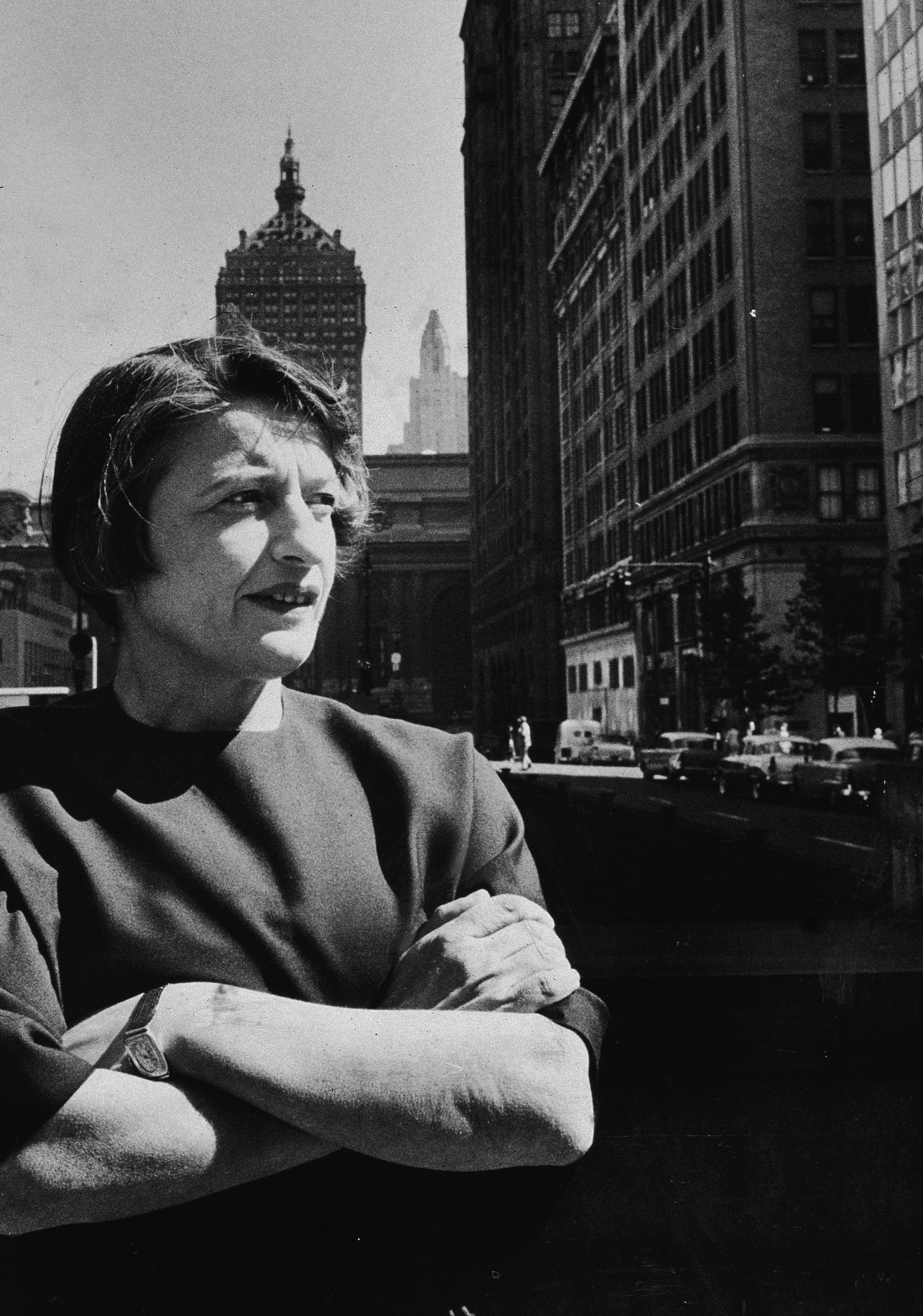

But if you want truly radical, here’s a nomination from maverick libertarian Justin Raimondo—uber-individualist writer and self-made philosopher Ayn Rand. She was an immigrant, which adds to the diversity factor. She has a larger following than any other nominee so far, and while her laissez-faire philosophy has a limited appeal in pure form, she played a major role in pushing American discourse toward more pro-capitalist opinion. True, she disliked women’s liberation and believed that a real woman wants to be dominated (a view that led her to an odd critique of the idea of a woman president, apparently on the grounds that a female leader would have no man to look up to). But she led a life remarkable unconstrained by traditional roles.

Besides, Rand worshipped the dollar sign as the supreme symbol of free enterprise and market value—even wearing a dollar-sign pin as a badge of honor. Surely that should give her extra points in a contest for the face of the new $10. Me? I vote for Elizabeth Cady Stanton, the more venerable and less outrageous individualist.

More Must-Reads from TIME

- Why Trump’s Message Worked on Latino Men

- What Trump’s Win Could Mean for Housing

- The 100 Must-Read Books of 2024

- Sleep Doctors Share the 1 Tip That’s Changed Their Lives

- Column: Let’s Bring Back Romance

- What It’s Like to Have Long COVID As a Kid

- FX’s Say Nothing Is the Must-Watch Political Thriller of 2024

- Merle Bombardieri Is Helping People Make the Baby Decision

Contact us at letters@time.com