On Thursday, when Pope Francis issued a much-anticipated encyclical (“a letter from the Pope to the bishops of the Roman Catholic Church, setting forth his views on anything he chooses for serious consideration, but not necessarily an infallible document,” as TIME once explained), he tackled one of today’s most controversial and pressing topics: the environment, and the climate’s impact on poverty.

The choice of topic drew criticism even before its publication. On Monday, Jeb Bush became the latest politician to posit that the Catholic Church should stay out of political and economic issues. But it’s actually been more than a century since the papacy changed its stance in favor of engaging with contemporary debates. One reason for that change was another papal encyclical, one of the most influential such letters in Vatican history: Rerum Novarum.

In the late 19th century, the Church’s long-strained relationship with wealth was being tested anew by the rise of unionism and socialism. Catholic leaders discouraged their flocks from participating in the then-growing labor movements. Pope Leo XIII saw that this situation would not do: though the Church was not a socialist organization, opposing the movements had the effect of alienating followers who just wanted a decent wage, higher living standards and a more fulfilling life. His response was Rerum Novarum, published in 1891. Its title—encyclicals take their names from the first words of the document—translates as “Concerning New Things.” It was a strong statement that the Church was paying attention to the world around it.

In 1931, when Pope Pius XI celebrated its 40th anniversary with his own encyclical, Quadragesima Anno (“In the 40th Year”), which addressed the social problems of the modern world, he called the earlier document the Magna Carta of the Church’s involvement in social justice. As TIME put it back then:

Forty years ago last week, the long-headed little old man in the Vatican peered out into the revolutionized industrial world and saw that all was not going to be peaceful. To 81-year-old Gioacchino Vincenzo Pecci, His Holiness Pope Leo XIII, who had been Civil Governor of Benevento and Governor of Perugia and far more a man-of-the-world than his dogmatist predecessor Pius IX, it seemed a good moment for Mother Church to say her say about social and industrial reform.’ So he composed and issued a great encyclical entitled Rerum Novarum (“Concerning New Things”). Firmly rejecting the new Socialism and its “community of goods” as “directly contrary to the natural rights of mankind,” he enunciated a platform which he was later to expand so as to put Mother Church on record for trades unionism, the eight-hour day, minimum wage laws, old age pensions and much else that was “radical” then, commonplace now.

“There is no intermediary,” he said, “more powerful than Religion (whereof the Church is the interpreter and guardian) in drawing the rich and the working class together, by reminding each of its duties to the other, and especially of the obligations of justice.” He recognized the occasional justification for strikes, the necessity for labor unions and decent wage standards, but he made clear that Mother Church could go no further. “As for those who possess not the gifts of fortune,” he said, “they are taught by the Church that in God’s sight poverty is no disgrace, and that there is nothing to be ashamed of in earning their bread by labor.”

One of the great qualities of Rerum Novarum, TIME noted when another decade had passed, was that its message could be adapted to its times: the support of the common people was unceasing, but the enemy evolved. Where socialism had been rejected in the 19th century for its focus on material goods, that rejection could later be applied to communism and then to Naziism. In later years, Rerum Novarum was also used as the theological basis for the Church’s support of Latin American Catholics who were opposing dictatorships, a policy that affected Pope Francis’ homeland of Argentina, where priests who opposed Juan Perón rose in power.

Rerum Novarum continued to influence the popes of the 20th century. Mater et Magistra (“Mother and Teacher”) was John XXIII’s response to the 70th anniversary of Rerum Novarum, and an attempt to bring its message firmly into the 20th century by addressing pressing global issues like the population boom and the power of technology for good and evil. Though he didn’t cite Communism by name, John XXIII continued his predecessors’ opposition to such movements—all while supporting non-ism “socialization,” or the general theory of working together (eg. through welfare programs) to help others in a society. His 1963 Pacem in Terris (“Peace on Earth”) continued the progressive and modern themes. In 1967, Pope Paul VI continued the trend with Populorum Progressio (“The Development of Peoples”), an encyclical that TIME joked “looked in some ways as if it had been drawn from a U.N. economic report.”

With his encyclical on climate change, Pope Francis is simply continuing a 124-year-old tradition.

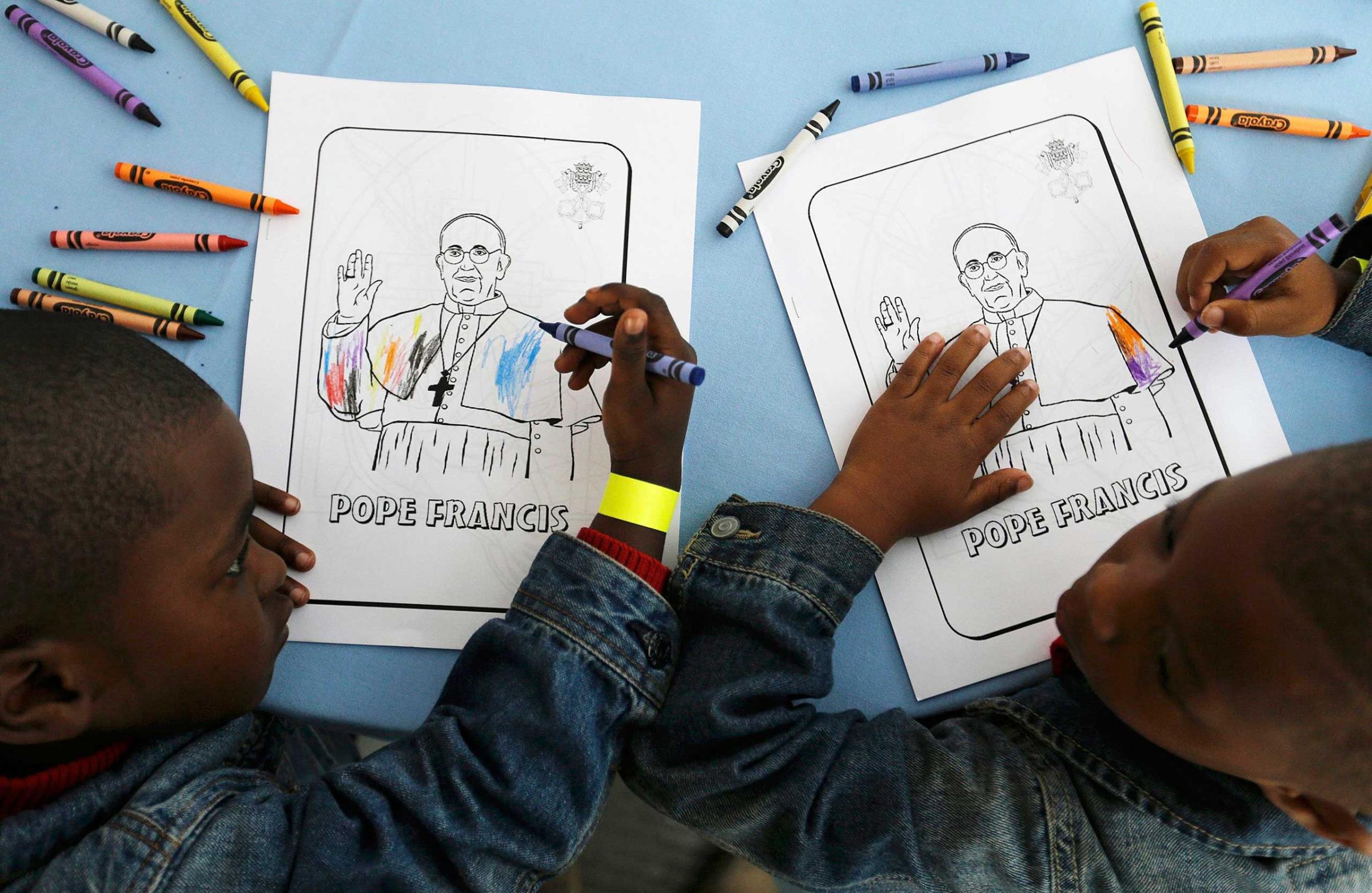

The Most Surprising Photos of Pope Francis

More Must-Reads from TIME

- Cybersecurity Experts Are Sounding the Alarm on DOGE

- Meet the 2025 Women of the Year

- The Harsh Truth About Disability Inclusion

- Why Do More Young Adults Have Cancer?

- Colman Domingo Leads With Radical Love

- How to Get Better at Doing Things Alone

- Michelle Zauner Stares Down the Darkness

Write to Lily Rothman at lily.rothman@time.com