The top U.S. military officer likened the expanding American footprint in Iraq Thursday to “lily pads” that will sprout across the pond known as Anbar Province, where the Islamic State of Iraq and Greater Syria seized the capital last month.

“Our campaign is built on establishing these ‘lily pads’ that allow us to encourage the Iraqi security forces forward,” Army General Martin Dempsey, chairman of the Joint Chiefs of Staff, told reporters during a visit in Italy. “As they go forward, they may exceed the reach of the particular lily pad”—leading to the creation of new ones.

While the strategy may be a new one since the U.S. pulled its forces out of Iraq in 2011, it has been done before. In both Afghanistan and Iraq, similar campaigns were carried out, often called “oil spot” or “ink blot” strategies.

Retired Army lieutenant colonel Andrew Krepinevich popularized the oil-spot notion in a 2005 article in Foreign Affairs, during the darkest days of the U.S.-led alliance in Iraq. “Since the U.S. and Iraqi armies cannot guarantee security to all of Iraq simultaneously, they should start by focusing on certain key areas and then, over time, broadening the effort—hence the image of an expanding oil spot,” wrote Krepinevich, who heads the non-profit Center for Strategic and Budgetary Assessments. Military scholar Max Boot advocated using what he called the “‘spreading inkblot’ strategy” in and around Baghdad in 2007.

It makes sense to establish protected bases in potentially-hostile terrain that can be linked to safer rear areas by air and roads. Each lily pad (or oil spot, or ink blot) gets bigger if its troops succeed in expanding the secure zones around them. Military momentum can lead to the creation of additional lily pads. Ultimately, they all expand until the entire region is free of enemy forces and secure.

Wednesday’s announcement boosts the number of U.S. bases in Iraq to five. “We’re looking all the time to see if additional sites might be necessary,” Dempsey said, although he said the two now in Anbar would probably suffice for that province. “I could foresee one in the corridor that runs from Baghdad to Tikrit to Kirkuk over into Mosul,” he added.

Dempsey detailed the evolving U.S. strategy the day after the White House said it would send up to 450 trainers and advisers to a base near Ramadi in eastern Anbar, within easy range of ISIS attacks. President Obama has pledged to keep U.S. troops out of combat with ISIS, even though allowing small numbers to embed with Iraqi forces to call in U.S. air strikes would make them more effective. The additional forces would push the U.S. troop total in Iraq to 3,550. Any decision to plant additional lily pads could require more U.S. troops in Iraq. U.S. troop strength in the 2003-2011 Iraq war peaked at 158,000 in 2008.

Adding U.S. troops to the Taqaddum military base is significant, Dempsey added, because “it gives us access to another Iraqi division and extends their reach into al Anbar province and gives us access to more tribes.” The U.S. is eager to enlist the Sunni tribes in Anbar in the fight against ISIS, whose members are Sunni. Sending the largely Shi’ite forces in Iraq’s national army to battle Sunnis in the Sunni heartland could inflame sectarian tensions.

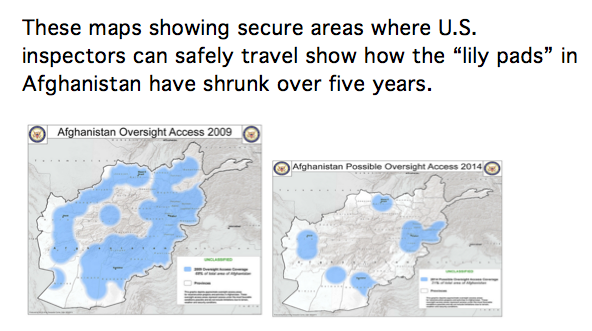

Of course, lily pads don’t always thrive. In Afghanistan, they’ve shrunk in recent years. John Sopko, the Special Inspector General for Afghanistan Reconstruction, warned two years ago that danger was spreading across the country and limiting the places his inspectors could visit to do their jobs. “U.S. officials have told us that it is often difficult for program and contracting staff to visit reconstruction sites in Afghanistan,” he said in October 2013. “U.S. military officials have told us that they will provide civilian access only to areas within a one-hour round trip of an advanced medical facility.”

The Afghan lily pads have continued to shrivel. “Americans can only really travel safely in Kabul, and for most part no travel outside of green zone in Kabul,” one U.S. official said Thursday, speaking of travel in and around the Afghan capital. “Helicopters are needed to travel less than a mile from the embassy to airport.”

More Must-Reads from TIME

- Cybersecurity Experts Are Sounding the Alarm on DOGE

- Meet the 2025 Women of the Year

- The Harsh Truth About Disability Inclusion

- Why Do More Young Adults Have Cancer?

- Colman Domingo Leads With Radical Love

- How to Get Better at Doing Things Alone

- Michelle Zauner Stares Down the Darkness

Contact us at letters@time.com