Diana Martínez makes her way down the busy downtown sidewalk with difficulty. She walks slowly, leaning on the crutches she has used all her life after contracting polio at barely nine months old.

Coming off the elevator of an old Parisian-style building in Buenos Aires, she enters the grandiose apartment of Argentine ballet legend María Fux. Diana leaves her crutches leaning against the wall of Fux’s studio, removes the leather and steel brace that allows her to stand upright by supporting her affected right leg, lies down on the floor and prepares to dance.

“Can you dance life? Yes, you can,” says 93-year old María Fux. “As long as you can move, as long you can crawl, but you need a stimulus. I provide that stimulus. They’re waiting for me to give it, and I give.”

Born in 1922, dance therapist Fux has spent the best part of her life giving people like Diana the gift of dance. Before that, a brilliant career in the 1940s and 50s that included being prima ballerina for the Cólon opera house in Buenos Aires had already made her a national celebrity. But in the 1960s Fux turned her attention to helping the physically challenged to move.

In the decades since then, her studio in Buenos Aires has been attended by people who would not previously have been considered able to dance. Blind students, deaf students, teenagers with Down syndrome, persons dealing with psychological stress, all were made to dance by Fux.

It is a work of infinite patience that is replicated today by devoted followers outside Argentina who have opened dance therapy schools to teach the “Fux method,” primarily in Italy, where the method has been followed since the 1990s.

“Her method is being taught in various countries in Europe, especially in Italy where there’s a school in Milan and another in Florence,” says Italian film director Ivan Gergolet, who was in Buenos Aires this week for screenings in Argentina of his feature-length documentary Dancing With Maria.

Gergolet’s 75-minute portrait of Fux and her miraculous work is a beautiful, emotional rollercoaster of a film that last month took the prestigious “Nastri d’Argento” documentary award in Italy. Screened for the first time at the Venice Film Festival last year, where it took another award, it has been playing to packed, tear filled audiences in the film documentary circuit across Europe since.

On a recent Tuesday morning, Fux was preparing to give a class at her spacious second-floor studio in Buenos Aires. Its three wide windows overlook bustling Callao Avenue, just a few blocks from the building of Congress. A mix of classical dancers, Down’s syndrome teenagers and ordinary students are arriving. Diana is already on the floor, stretching in preparation for the class.

“Dance for me was something prohibited until I discovered Fux six years ago,” says Diana, 53. “Thanks to her I’ve been able to recover my femininty. Imagine, having had a rigid body for so long, to discover I could dance, it helped me overcome social prejudices and my own prejudices regarding what I could do.”

Fux strikes a distinctly regal pose as she sits down for the interview. “How do I look?” she asks, laughing. “I am 93 but still giving classes.”

Although she denies she has a method per se, Fux says that testing the limits of the human body is part of it. “I’m interested in limits, my limits and the limits of other people. I give that limit that says, “No, I can’t,” the chance of saying “Yes, I can.” It involves creativity. One and one is not always two, sometimes it is five, sometimes three, sometimes nothing.”

Fux says the elasticity of limits was impressed upon her by her mother, who escaped to Argentina with her 14 siblings before the First World War, fleeing from the anti-Jewish pogroms in Odessa in what is now Ukraine.

Shortly after arriving in Argentina, Fux’s mother caught an infection that required the removal of her kneecap, leaving her with a limp. “I became interested in limits because of my mother, I’ve never seen a woman with as much movement as she had,” Fux says. “She moved, she cooked delicious meals, she gave me and my sisters the chance to say “Yes, I can.” I saw how my mother stretched her limit through movement. I am my mother’s dancing leg.”

It is a life lesson that for over five decades she has imparted to various generations of Argentines, many of whom are crowding the current screenings of Dancing With Maria in Buenos Aires.

“Maybe it’s not so surprising nowadays, but a few decades ago when I attended her studio it was completely shocking and unheard of to have physically and mentally challenged students at a dance class,” said a former student at a screening Sunday night at which she received a standing ovation as the credits rolled.

In one astounding scene in the film, Fux leads a group of blind students through a heart-wrenching dance in her studio. “Blind people need to feel they can move without bumping into anything,” she says in the film. “But we are also blind and deaf sometimes. There’s two ways to see life, the way people think you are and the way you actually are.”

Such is the strength of Fux’s following in Italy that spontaneous flashmobs, in which Fux method students swarmed to dance in the street outside the cinema, occurred in nine cities where the film was screened. In Buenos Aires too, the screenings have been preceded by similar spectacles.

The film was born from the admiration of Gergolet’s wife, the Italian dancer Martina Serban, for Fux. “I met Fux in Italy in 2006. She has a charisma, a power, she transmits love. We are used to the idea that if someone has a limit, you have to help them. But she helps in a different way, by letting the student come up against their own limit and saying ‘I trust you can do it’ to them.”

Convincing Fux to participate in the film was not easy. The ballerina is practically unapproachable, entering the class once it is assembled, leaving immediately after it’s over and seldom interacting outside the lesson. “I often don’t even know their names, but I know who they are,” says Fux.

“We lied to her,” says Gergolet. “We told her we were from an Italian television station and that we wanted to interview her.” Back home in Italy, Gergolet showed the material to a film producer, who became mesmerized with Fux and put his full weight behind the project.

Despite the thousands of tears being shed at the film’s showings, Fux remains somehow detached from it all, continuing to give her weekday classes and weekend seminars in her giant Buenos Aires apartment. At Tuesday’s class, Diana, the polio victim, suddenly starts separating from the floor. In a slow, gyrating movement, she rises on her twisted right leg, stands upright, and dances.

“When I started with Fux I felt very bad because I couldn’t dance on my feet,” says Diana. “But that’s because I was thinking. Now I no longer think about what I can’t do, I just move.”

A legendary figure of the dance world decades before Gergolet and his wife were even born, Fux dismisses questions about her meetings with Maya Plisetskaya at the Bolshoi Theatre in Moscow in the 1950s or her training with Martha Graham in New York in the same decade. (Graham sent Fux back to Argentina after seeing her perfom. “She told me I didn’t need any master, that I already had my masters inside me.”)

Fux’s thoughts are turned instead to the mystery of movement and the testing of limits through dance and music. “Music is like a string,” she says. “Sometimes it breaks, sometimes it continues. That’s all. It’s not a note, C or A. It’s a movement in space that creates drawings. That’s something you can understand, that I can understand, that everyone understands. It’s about becoming a better person. That’s what’s most important.”

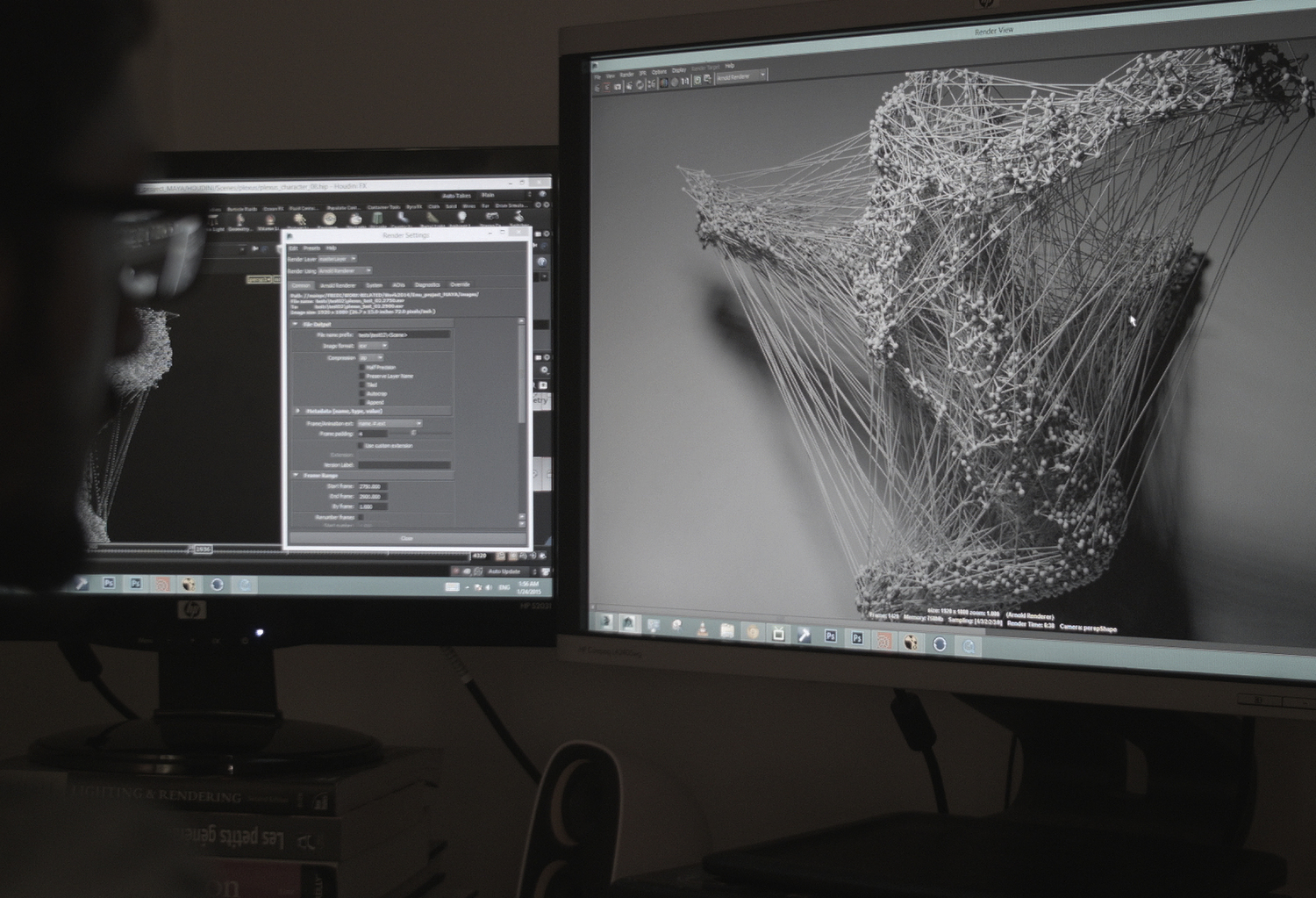

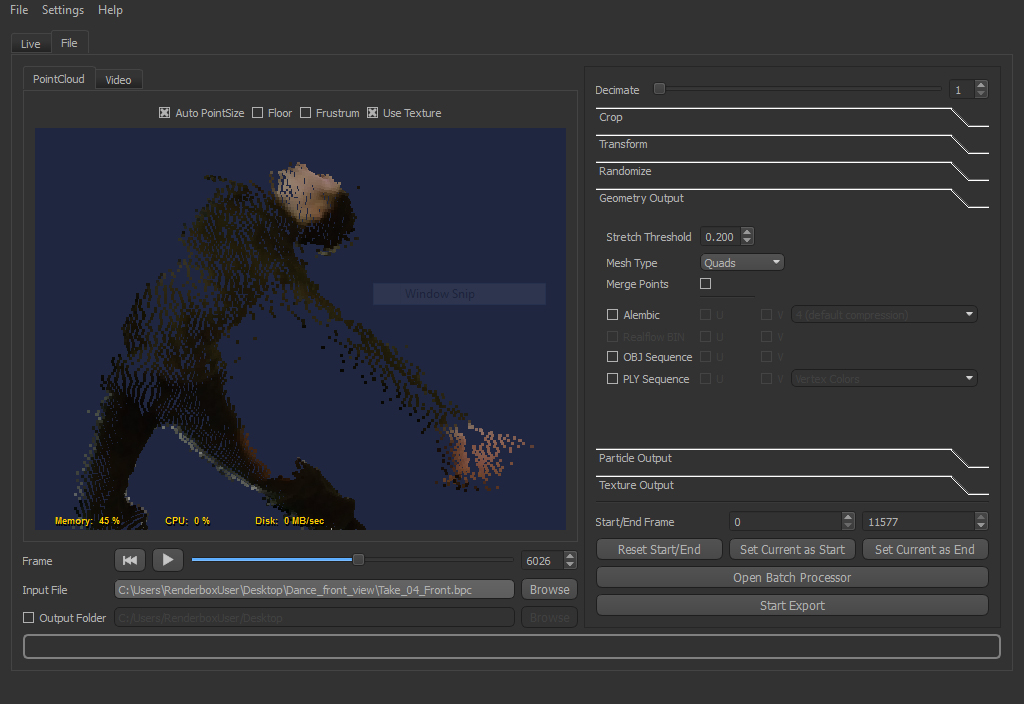

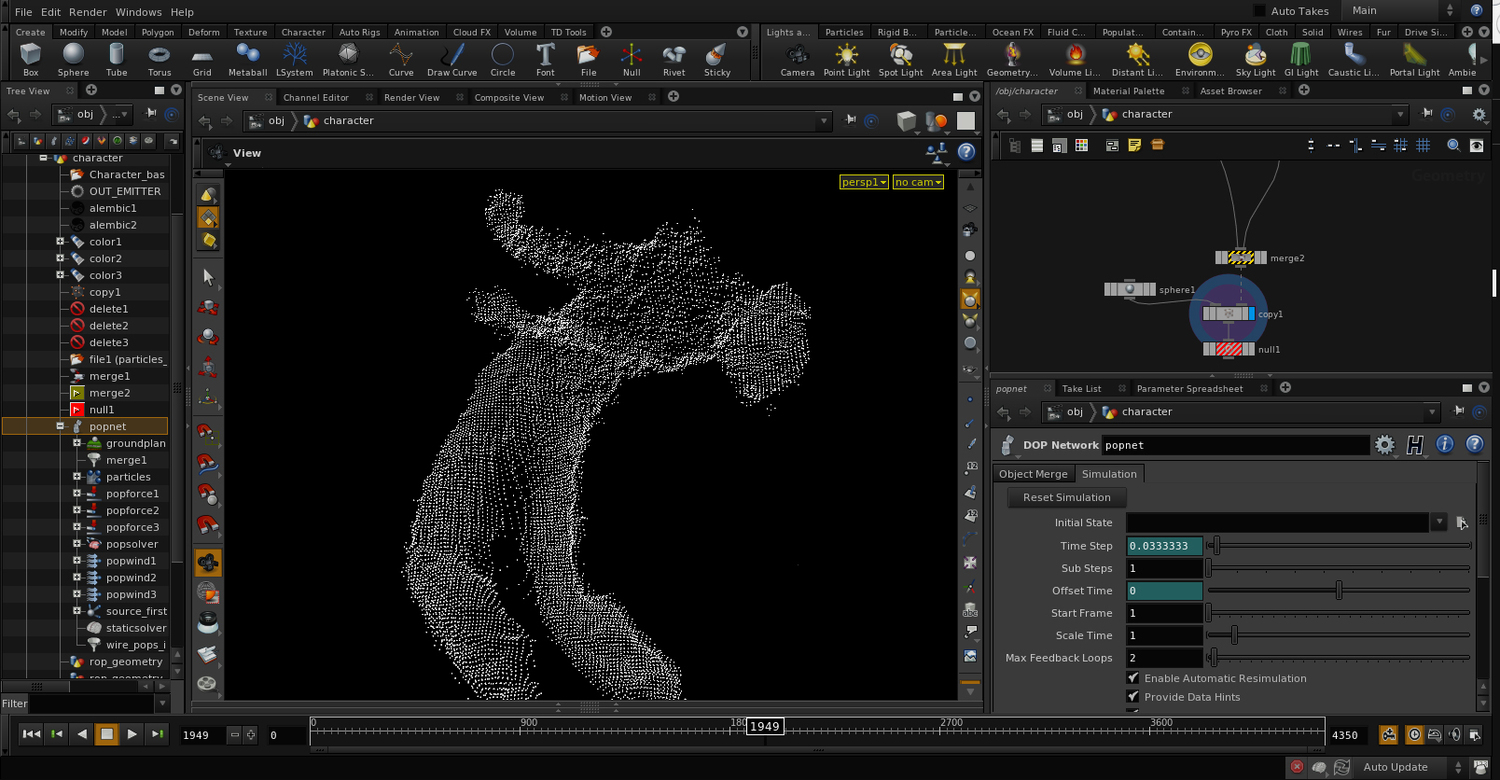

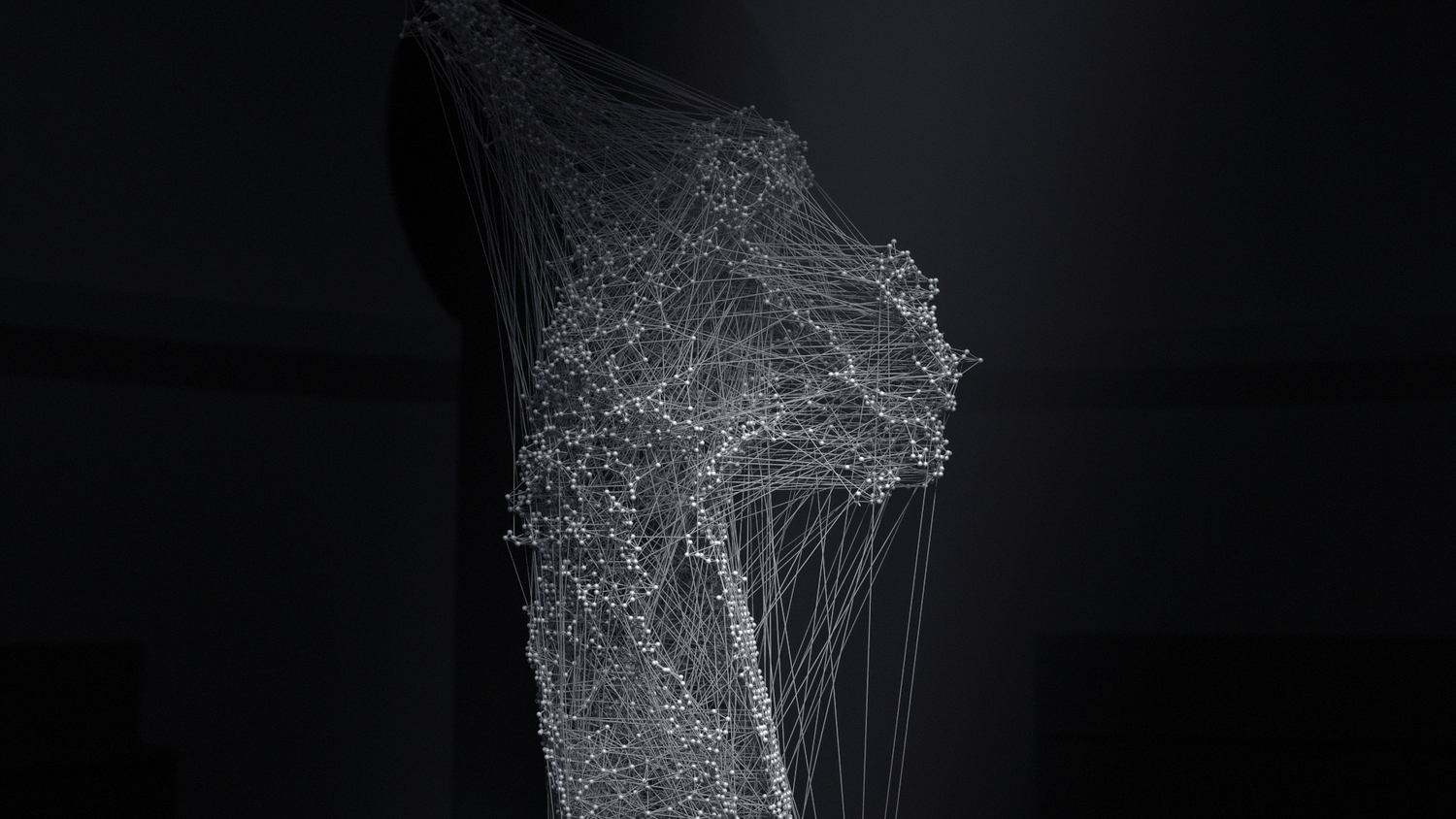

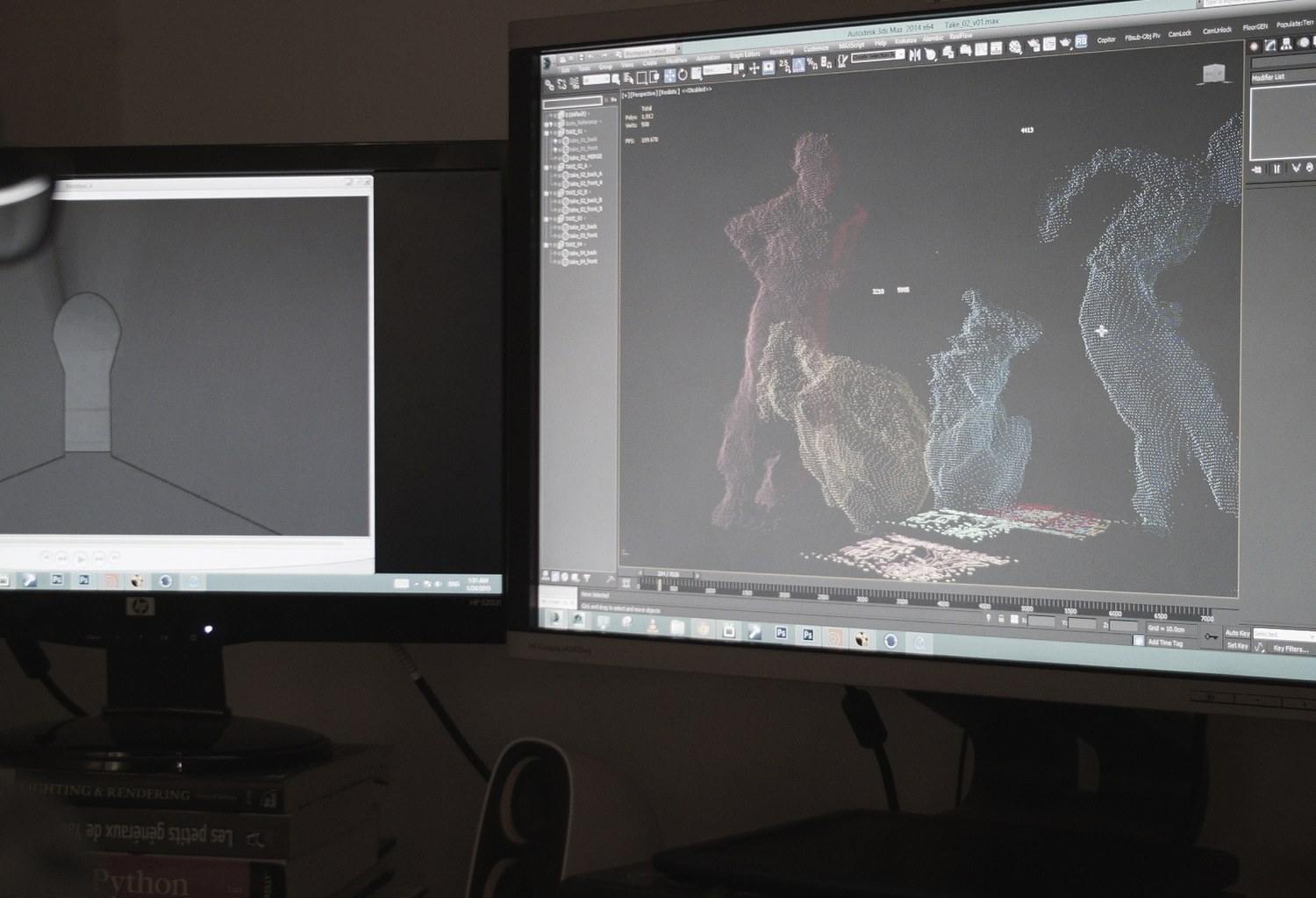

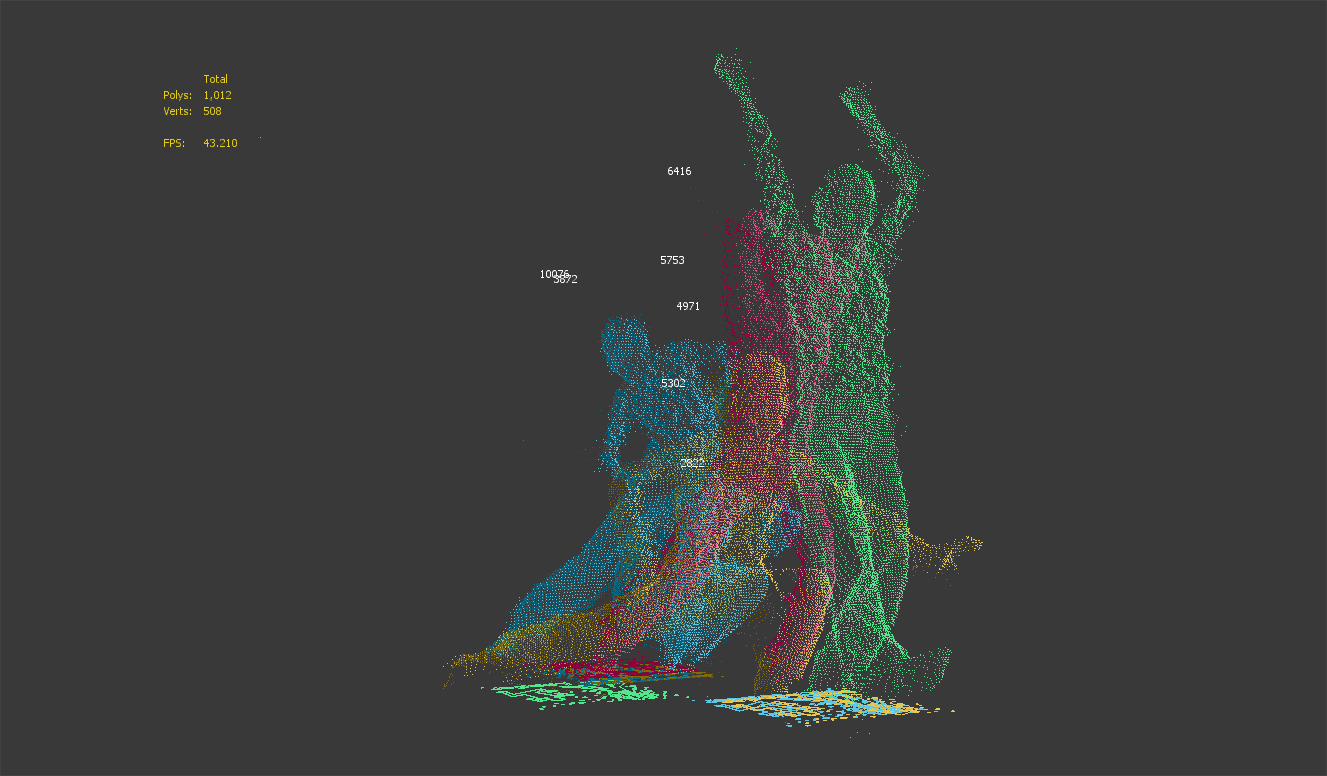

These Are the Incredible Images a Computer ‘Sees’ When a Person Dances

More Must-Reads from TIME

- L.A. Fires Show Reality of 1.5°C of Warming

- Home Losses From L.A. Fires Hasten ‘An Uninsurable Future’

- The Women Refusing to Participate in Trump’s Economy

- Bad Bunny On Heartbreak and New Album

- How to Dress Warmly for Cold Weather

- We’re Lucky to Have Been Alive in the Age of David Lynch

- The Motivational Trick That Makes You Exercise Harder

- Column: No One Won The War in Gaza

Contact us at letters@time.com