Zócalo Public Square is a magazine of ideas from Arizona State University Knowledge Enterprise.

At some point, every Native American actor comes to a career crossroads and has to answer the question: Do I participate in stereotyping or maintain my cultural integrity?

As a Navajo man, I answered that question early in my acting career. Fresh out of Yale with a bachelor’s degree in film studies, I moved to Albuquerque in 2010 when the New Mexican film industry was booming. To build up my resume, I took on parts in various short films—including one memorable role as an “Indian” shaman.

Acting parts for Native Americans are few and far between, so I felt I couldn’t say no to the gig. But as I climbed into the feathered costume and began to apply “war paint” to my face, I began to feel very uncomfortable. Even though I’m not of a Plains tribe (as of 2013, the number of federally recognized tribes in the U.S. was 566), I knew that this kind of regalia was not meant for casual, every-day wear. For many tribes, including mine, feathers are sacred.

Looking at myself in the mirror in full costume, I felt shameful for mocking my spirituality. I promised myself I’d never play “Indian” again—and since then have turned down several auditions for big budget films.

Last month, 12 Native American actors walked off the set of Adam Sandler’s forthcoming comedy, The Ridiculous Six. A few days later, Indian Country Media Today leaked several pages from the script, which features jokes depicting Native Americans as dirty, animalistic backdrops.

The film’s producer, Netflix, was quick to defend Sandler’s jokes as “a broad satire of Western movies and the stereotypes they popularized…” In actuality, however, these jokes aren’t anything novel or creative. They’re uninspired facsimiles of old stereotypes that stem from late 19th-century Wild West Shows.

Starting in 1883 with Buffalo Bill, these shows toured the United States to display their “tamed” wild Indians in extravagant rodeo performances. Many prototypes of Native American stereotypes (such as living in teepees, hunting for buffalo, scalping enemies, wearing feathered regalia, and having a savage demeanor) gestated in these vaudevillian theatrics.

Often, Native Americans in Wild West shows reenacted crippling defeats such as the Wounded Knee Massacre. These shows celebrated the conquest of the West and the decimation of the Native American population, but for the Native American actors who participated in them, they were also a means of earning money for their families.

In 1913, director Thomas Ince hired Native Americans who had performed in those traveling shows to work at his film production studio in Santa Ynez Canyon near Santa Monica. He also recruited several Sioux people from the Pine Ridge Reservation in South Dakota. In exchange for room and board, the actors were cast in Ince’s films or loaned out to other directors.

During that decade, white directors like Ince, Cecil B. DeMille, and D.W. Griffith laid the foundation for the Western narrative in Hollywood by borrowing heavily from Wild West shows. In Griffith’s The Battle of Elderbusch Gulch (1913), an unspecified tribe of savage “Indians” celebrated their annual “feast of dogs” before raiding a nearby white establishment.

Silver-screen tales about defeating Native American tribes proved to be hugely popular, so Hollywood churned them out. In most Westerns, white cowboys represent the shining future, whereas “Indians” are the dimming past. Cowboys are logical. “Indians” are irrational. Together, cowboys and Indians are the ego and the id of Anglo-Saxon identity.

But even though Western movies were brimming with stereotypical “Indian” roles, making a living in the film industry was difficult for Native American actors, many of whom left reservations after World War II to work in L.A. In Reimagining Indian Country, Nicolas Rosenthal writes about how the more prominent, higher-paying “Indian Chief” roles went to non-Native American actors, while Native Americans were stuck in the background—and paid a lower rate than other actors in the same supporting parts.

In 1926, several Native American actors created the War Paint Club, to provide support to Native American actors looking for work in L.A. and to encourage filmmakers to cast them in the “Indian Chief” roles. The War Paint Club also demanded that film companies pay Native American actors the same rate as non-Native American actors. They organized public powwows in the hopes of dispelling negative stereotypes perpetuated by Westerns.

The War Paint Club evolved into the Indian Actor’s Association in 1936, led by Luther Standing Bear, William Eagleshirt, and Richard Thunderbird. That in turn was later absorbed into the Screen Actors’ Guild in the early 1940s.

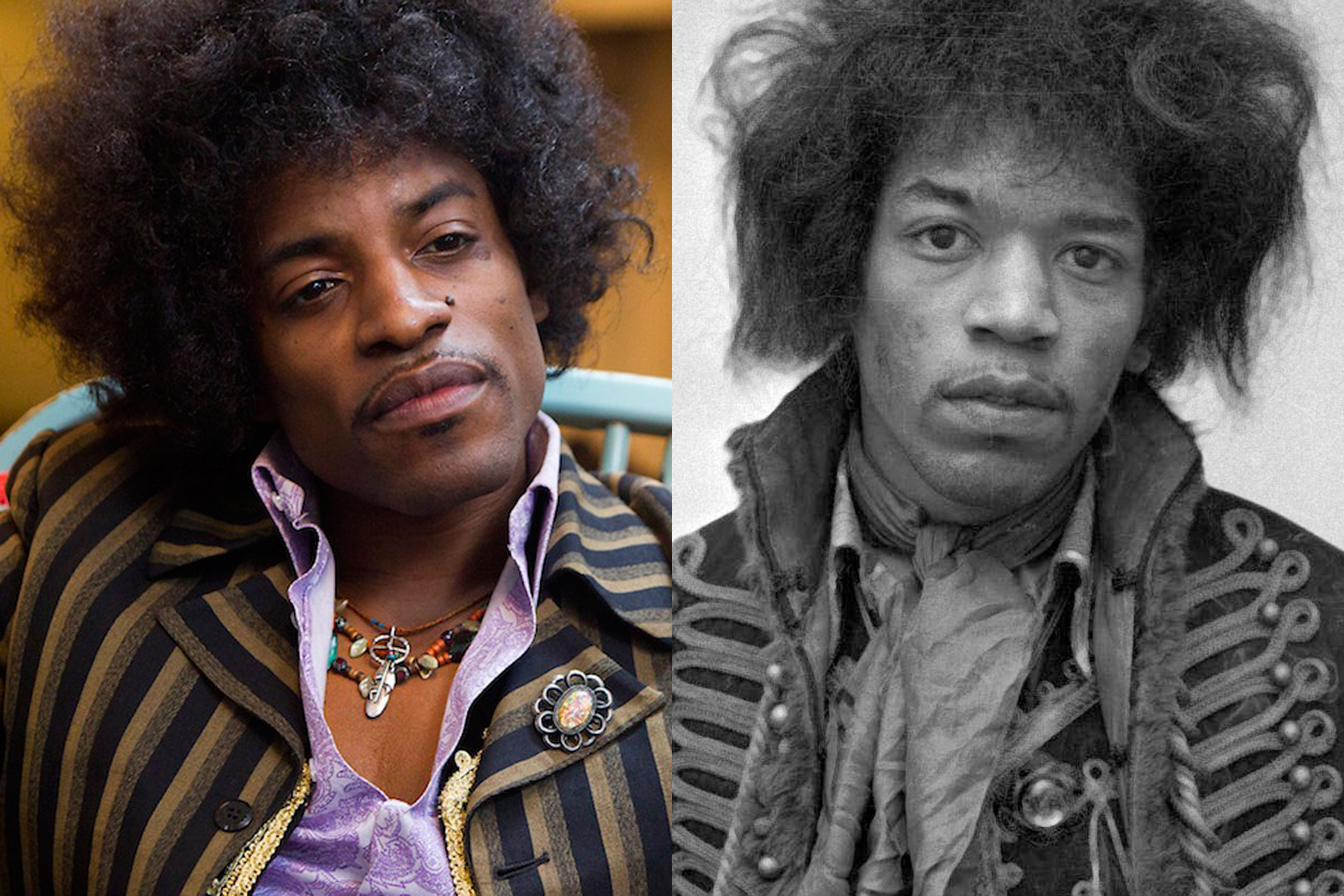

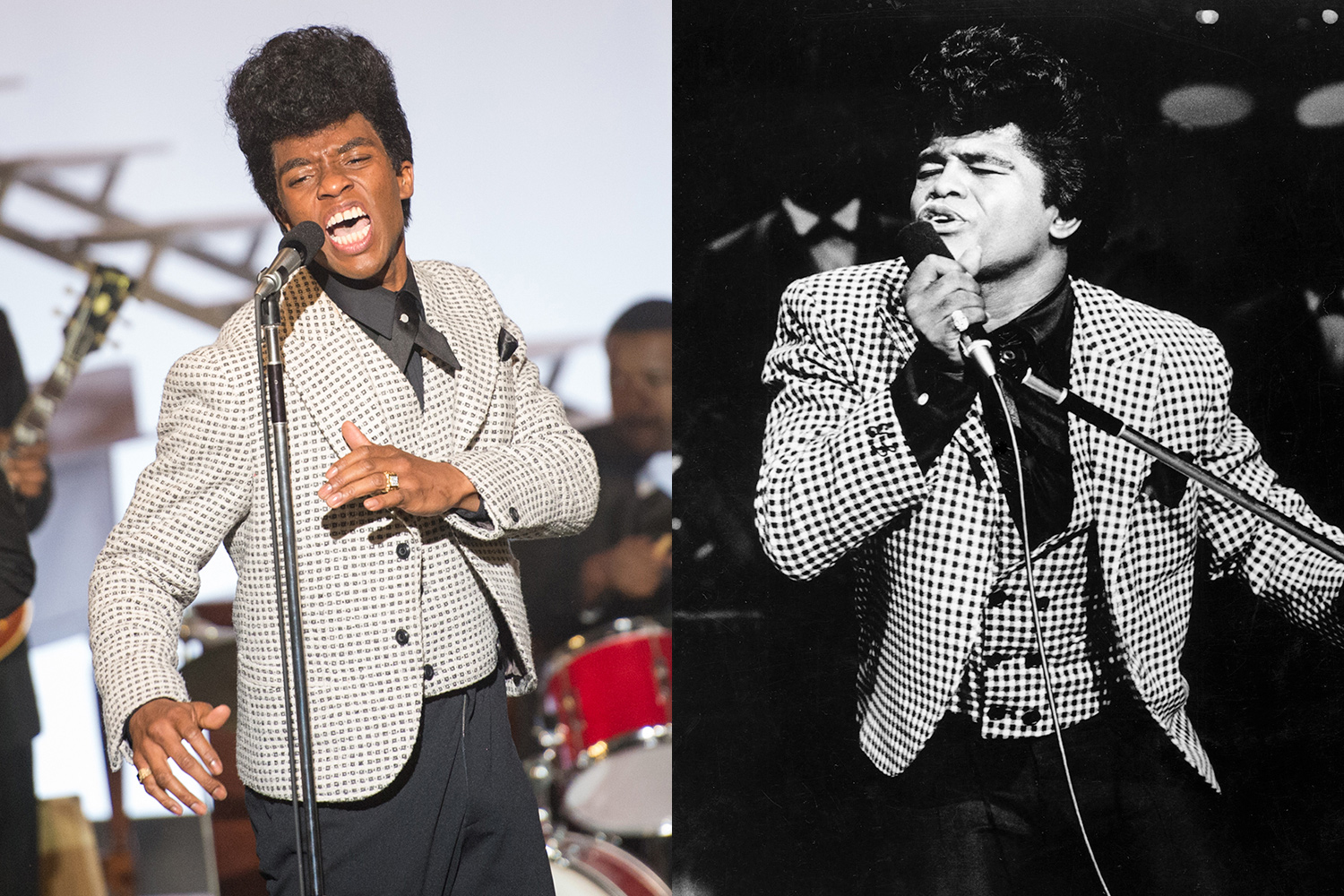

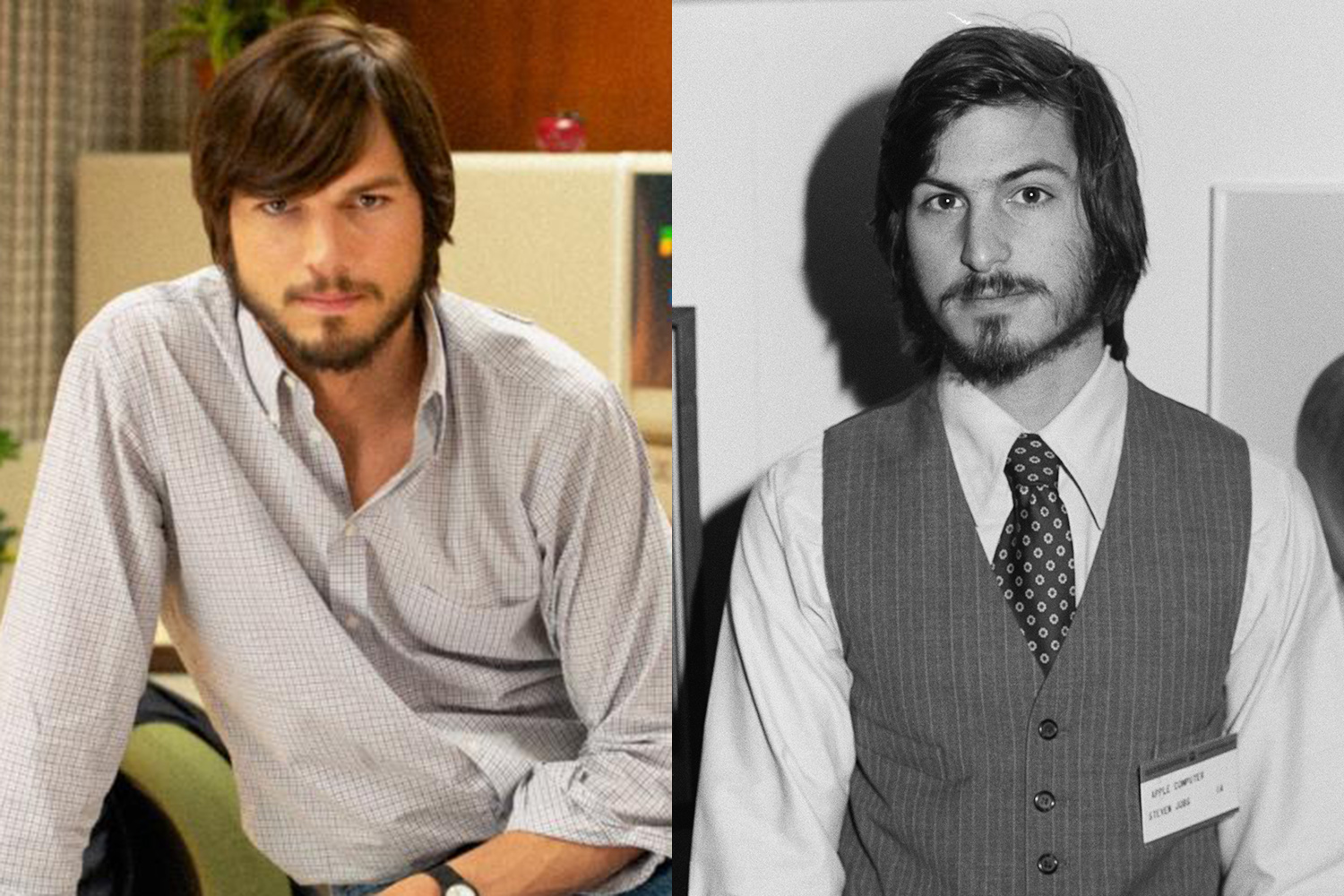

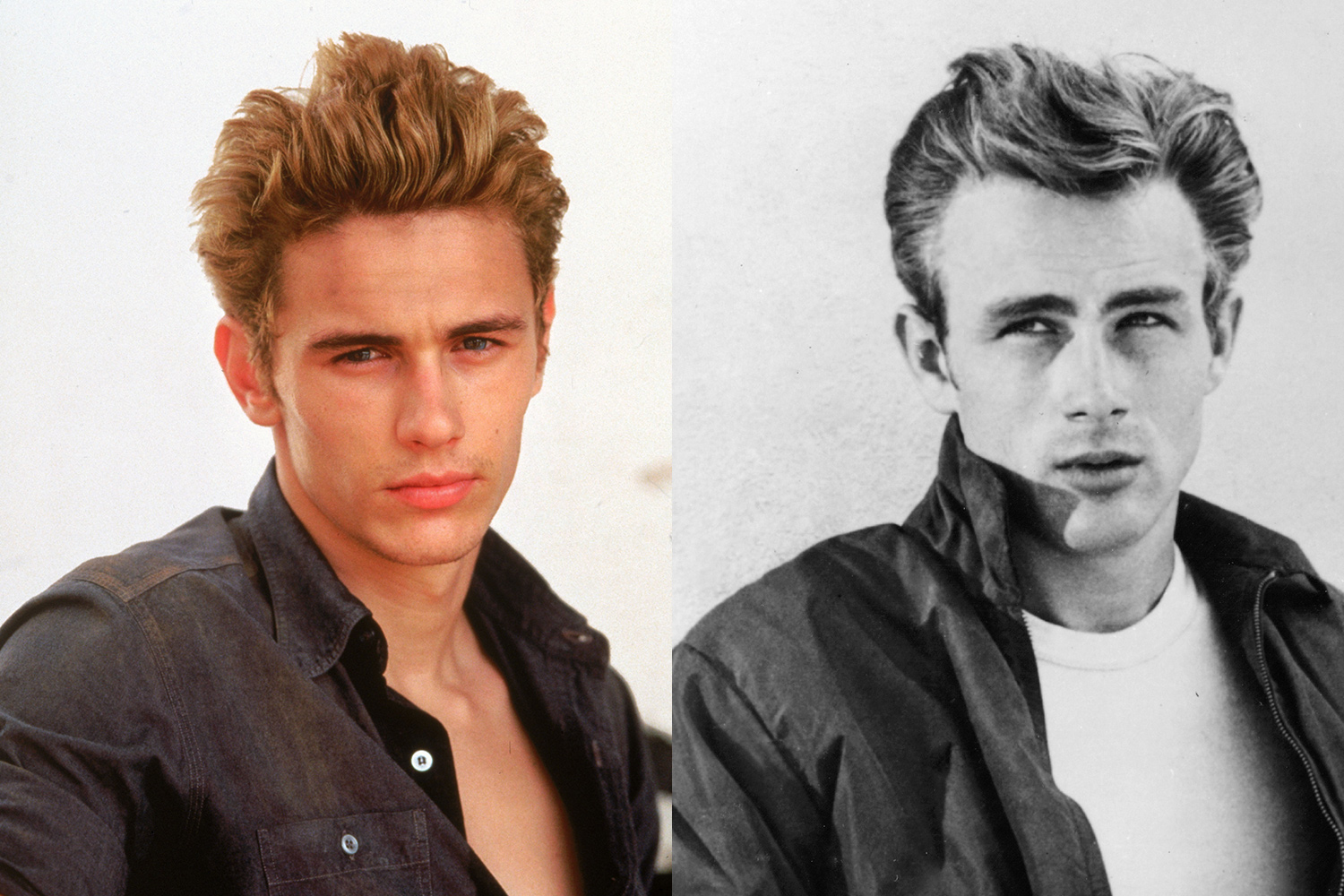

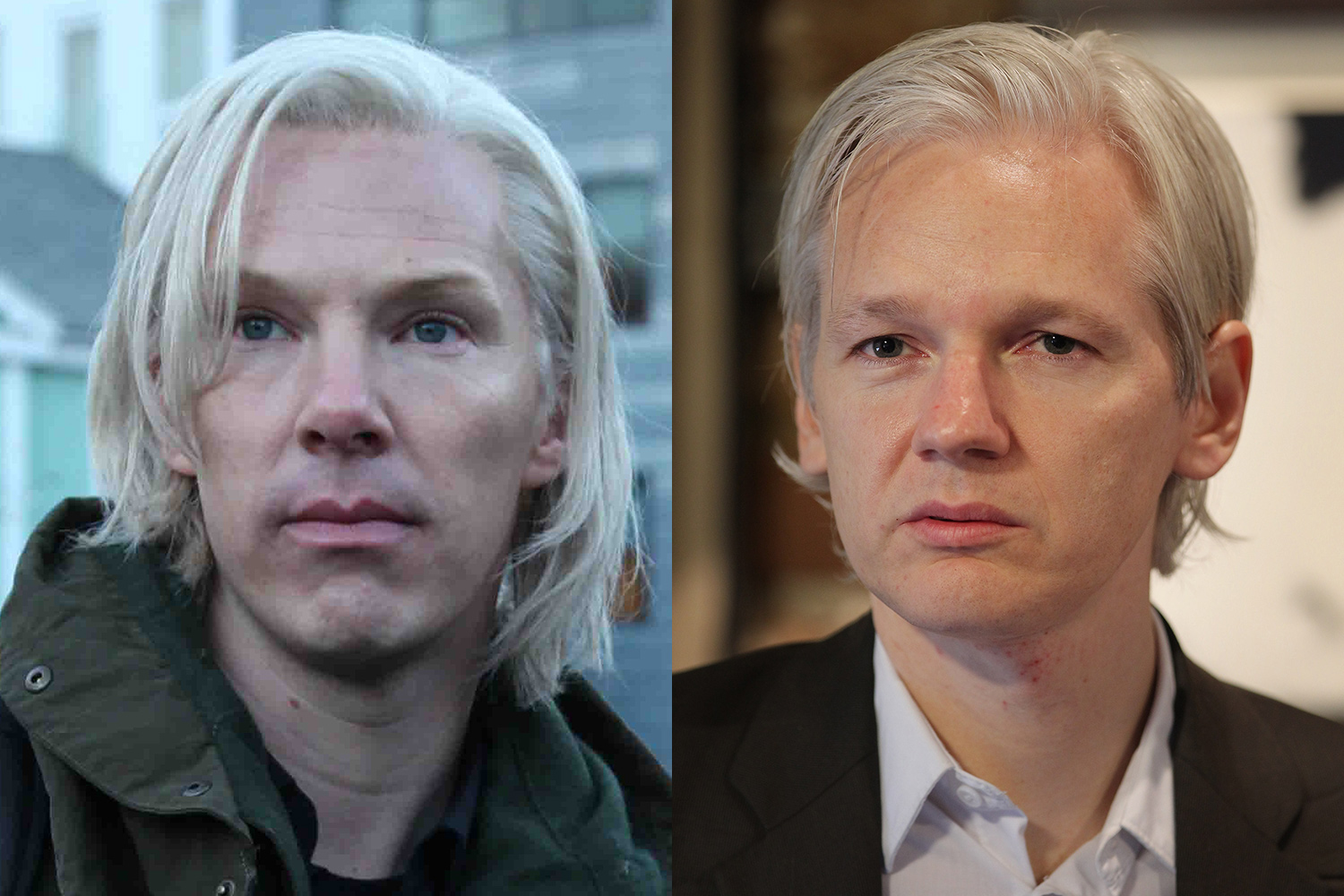

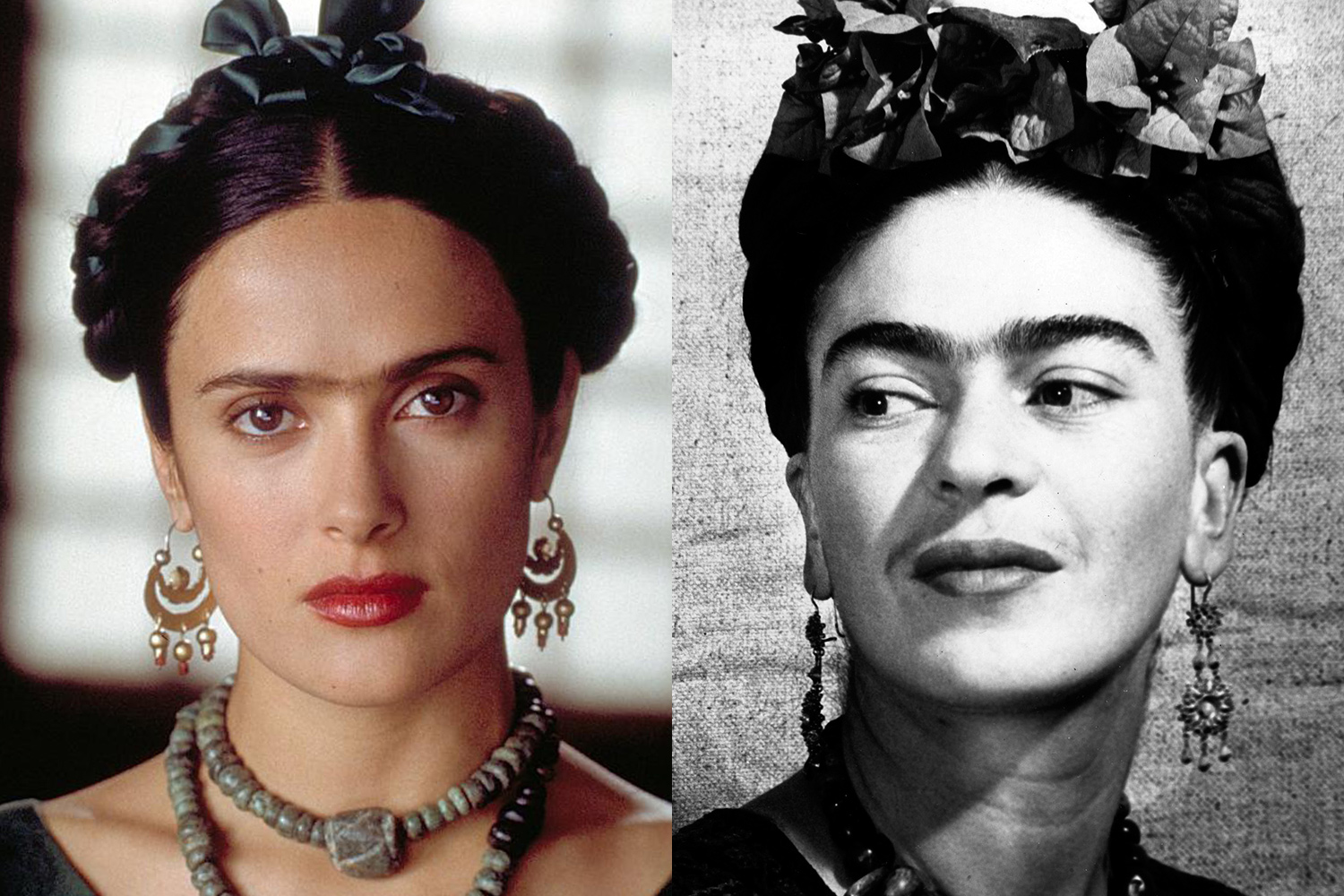

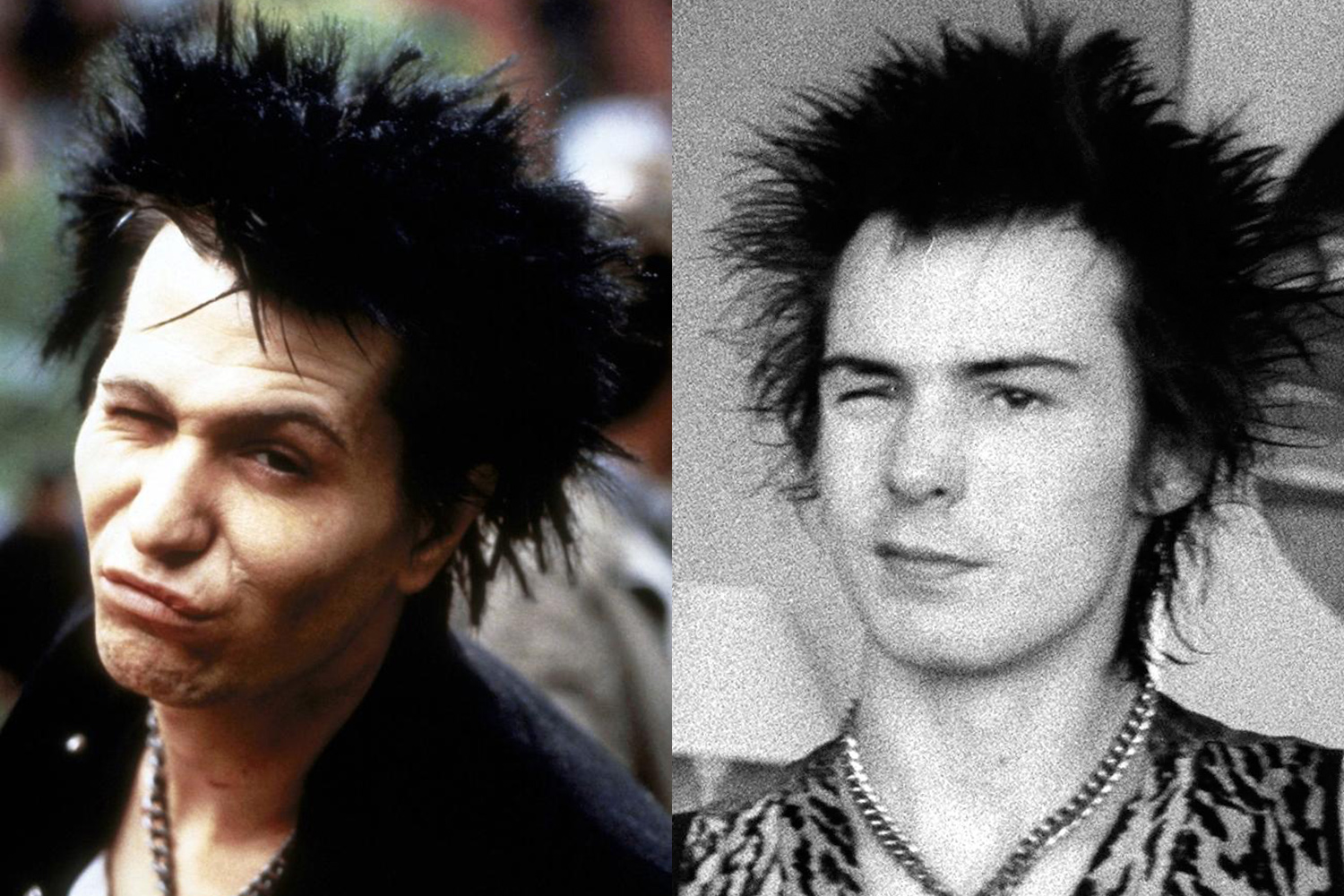

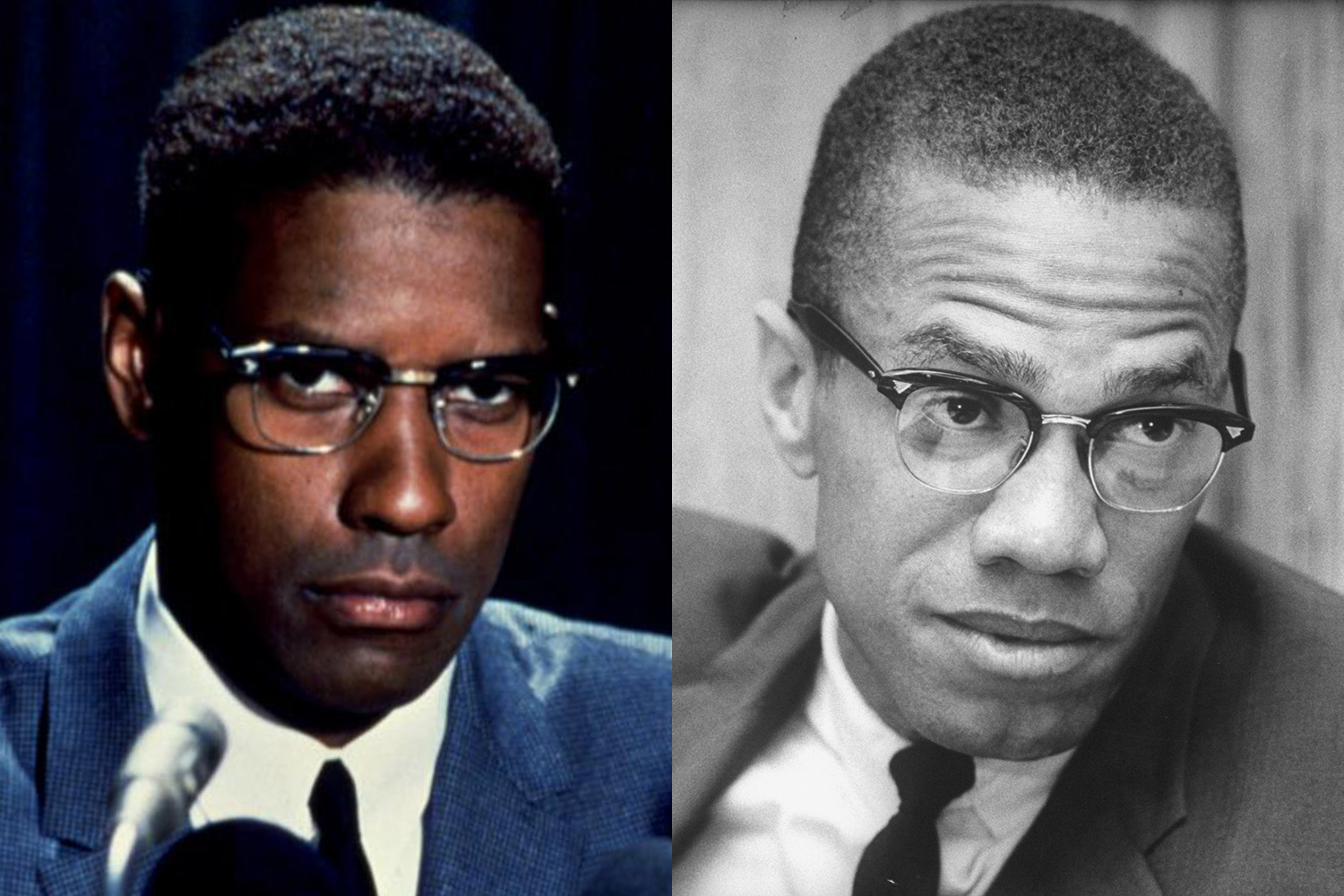

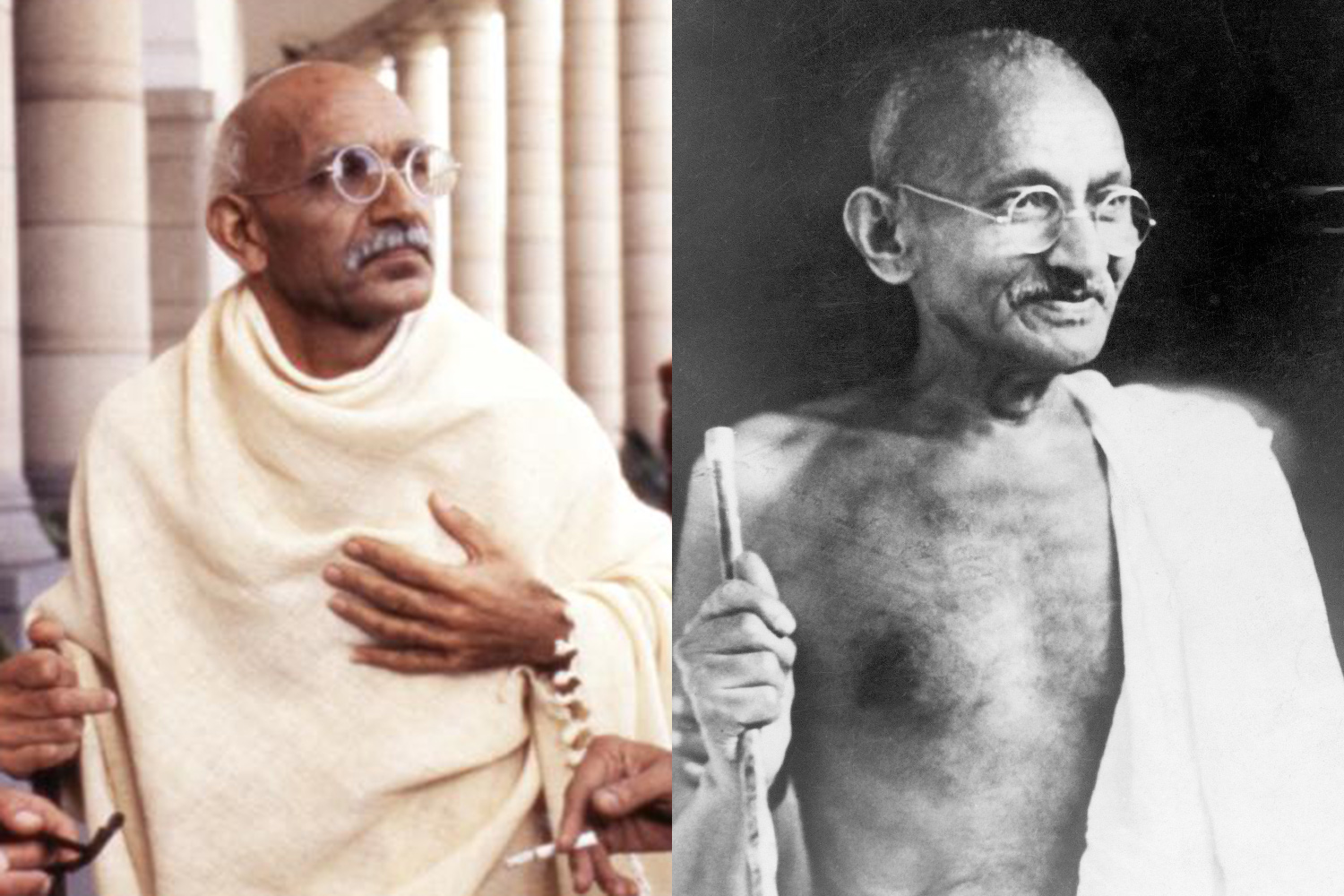

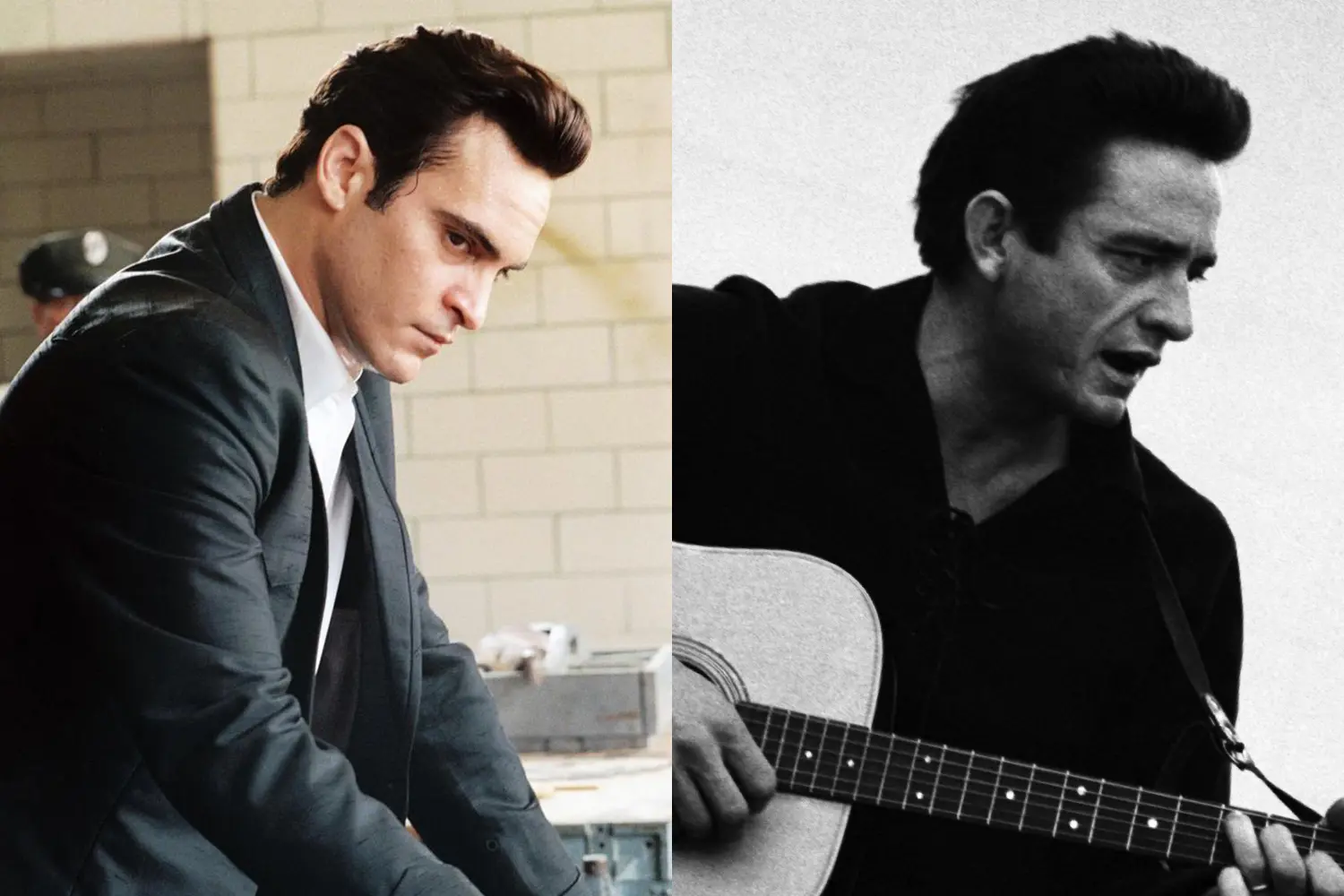

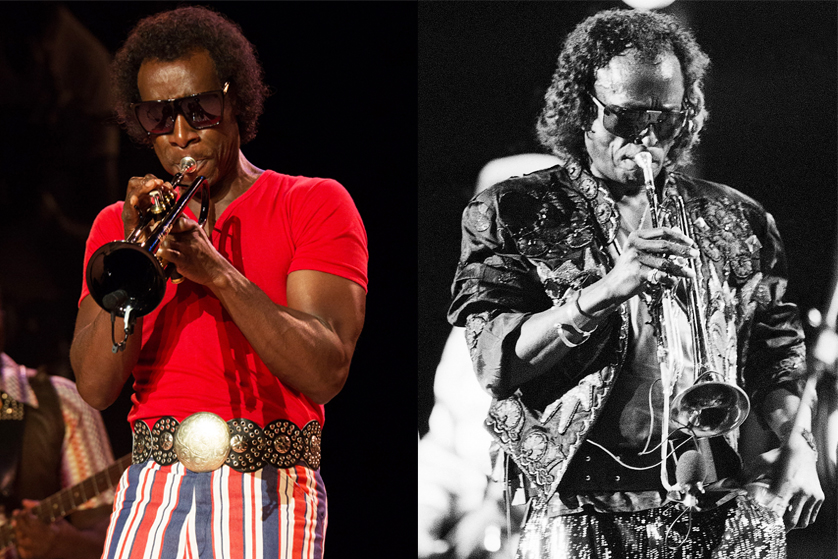

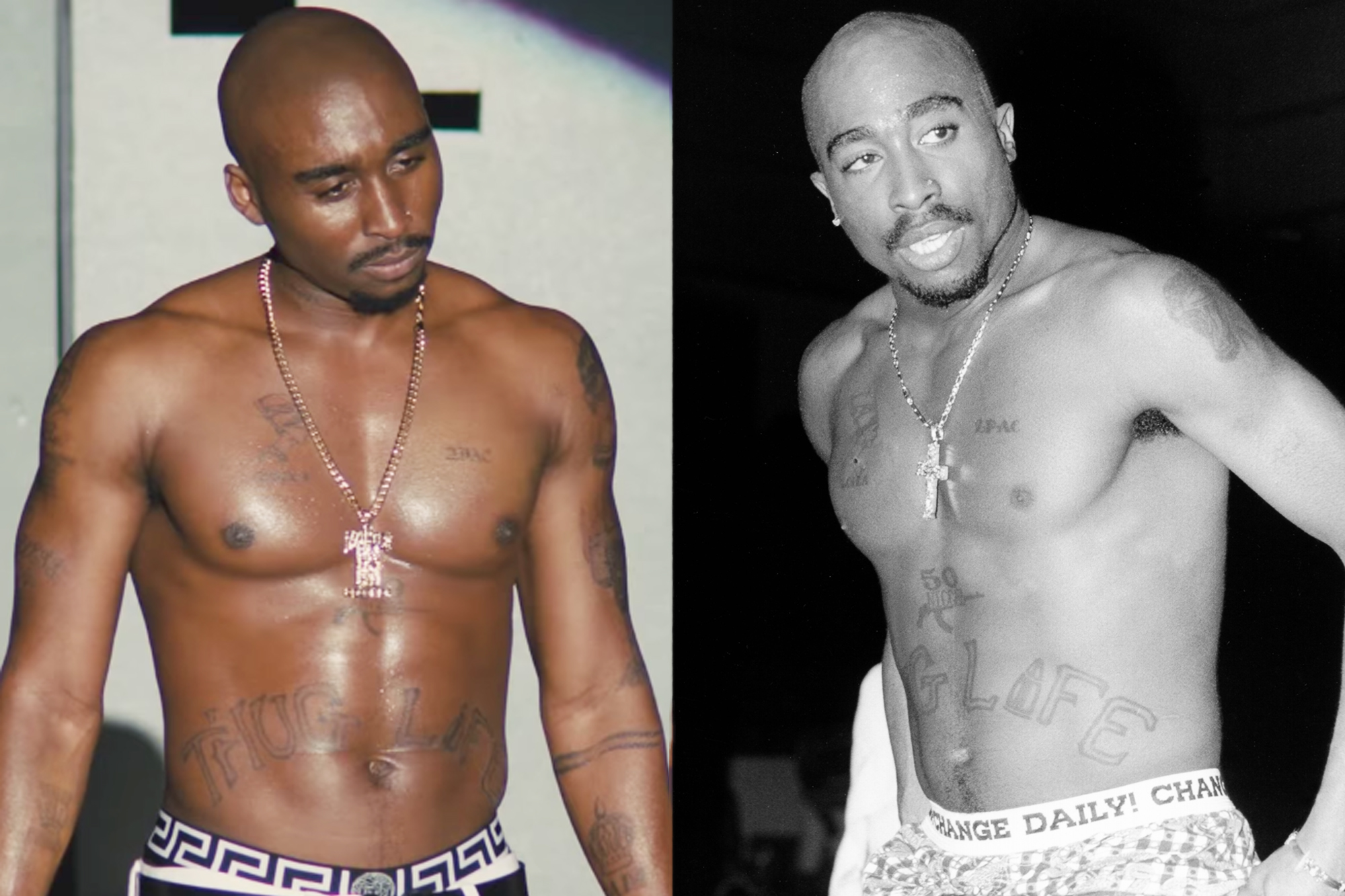

Biopic Actors and Their Real-Life Counterparts

During the American Indian Movement of the 60s and 70s, television news channels broadcasted Wes Studi’s occupation of Wounded Knee, and a wider United States audience was exposed to the actual conditions of reservation life.

Around the same time, the “Indian” stereotype evolved from reactionary savage to the romantic victims of manifest destiny — from the vicious and blood thirsty Geronimo seen in Stagecoach (1939) to the Geronimo who fights to protect his tribe seen in Geronimo (1962).

This softening trend grew, as Native American actors assumed more prominent (if still rather one-note) roles, as with Will Sampson in One Flew Over the Cuckoo’s Nest (1975), Graham Green in Dances with Wolves (1990), and Russell Means in The Last of the Mohicans (1992).

Outside of the Hollywood system, Native American artists continually wrote, produced, directed and acted in their own short film productions. In 1909, James Young Deer, of the Nanticoke tribe, began his directing career with The Falling Arrow. In 1966, several Navajos near Pine Springs, Arizona, participated in an anthropological study that produced several short films known collectively as Navajos Film Themselves. Victor Masayesva, Jr. directed Weaving in 1981.

Starting with Chris Eyre’s Smoke Signals in 1998, Native American filmmakers began producing feature length movies on par with the Hollywood production system. In Canada, Zacharias Kunuk brought an Inuit legend to life with Atanarjuat: The Fast Runner (2001), while Georgina Lightning explored the horror genre with Older Than America (2008). Director Neil Diamond explored the birth of the Hollywood “Indian” stereotype in the documentary Reel Injun (2009). Jeff Barnaby released his visceral Rhymes for Young Ghouls (2013). And Sterlin Harjo examined the Muscogee-Creek hymns in his documentary, This May Be The Last Time (2014). Just to name a few.

Meanwhile, the Hollywood mainstream has cranked out a fledging resurgence of Westerns with (mostly panned) movies such as Cowboys & Aliens (2011) and The Lone Ranger (2013). In these projects, Native American actors have been restricted to background roles—which brings us back to some of what’s wrong with The Ridiculous Six.

I have personally experienced the level of ignorance that results from one’s only exposure to a culture being what one sees in movies. During my orientation week freshman year in 2006, many of my classmates, when they discovered my Navajo heritage, seemed to think I lived in a teepee and hunted buffalo in the plains on horseback. (For the record, Navajos are primarily farmers and shepherds. Our traditional houses, hogans, are used mainly for ceremonial purposes. We drive cars to get to places. So, no.)

Further, they wanted to know why I didn’t wear any feathers or have long, black hair. I was shocked by how little my fellow students knew about Native Americans, and how much they based their perception of me and my heritage on what they had seen in westerns.

The most troubling aspect of The Ridiculous Six is how the script depicts Native American women as promiscuous, by using names such as “Sits-On-Face.” This may be presented in a spirit of levity for an audience that appreciates fart jokes as much as Sandler, but it undermines the dire circumstances of Native American women, who experience high levels of sexual assault and violence.

In all likelihood, of course, Sandler’s team wasn’t aware of these disturbing statistics when they began writing The Ridiculous Six. But their ignorance isn’t an excuse. Such carelessness with racist, sexist jokes can establish misperceptions that are hazardous in real life to real people.

Brian Young is a Navajo filmmaker currently living in Albuquerque, New Mexico. Among his projects are two short animated films (Lady and the Eagle and Rainbow Bird) and Yeego Nitl’aa’, an exercise video series narrated in Navajo. He wrote this for Thinking L.A., a partnership of UCLA and Zócalo Public Square.

More Must-Reads from TIME

- Donald Trump Is TIME's 2024 Person of the Year

- Why We Chose Trump as Person of the Year

- Is Intermittent Fasting Good or Bad for You?

- The 100 Must-Read Books of 2024

- The 20 Best Christmas TV Episodes

- Column: If Optimism Feels Ridiculous Now, Try Hope

- The Future of Climate Action Is Trade Policy

- Merle Bombardieri Is Helping People Make the Baby Decision

Contact us at letters@time.com