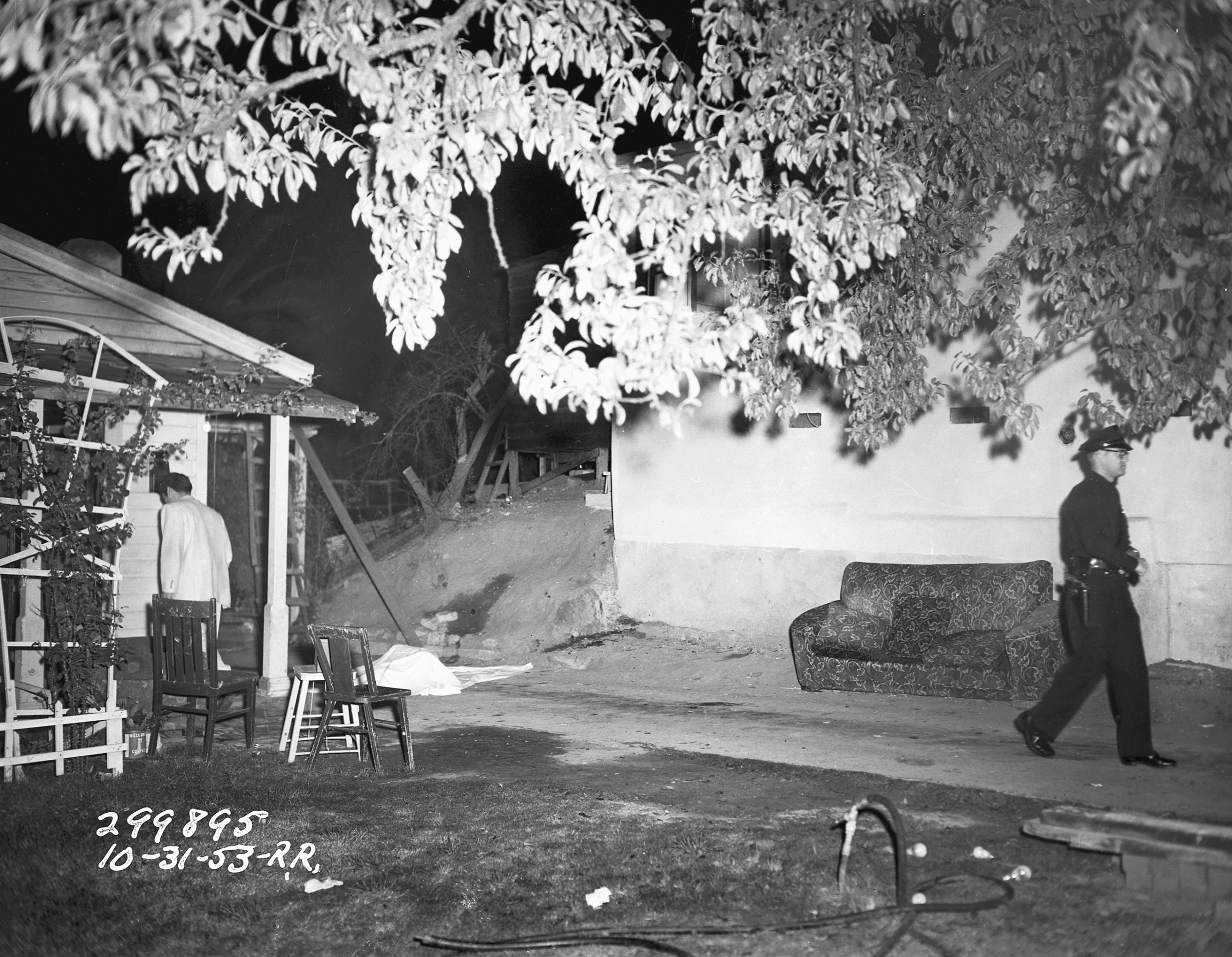

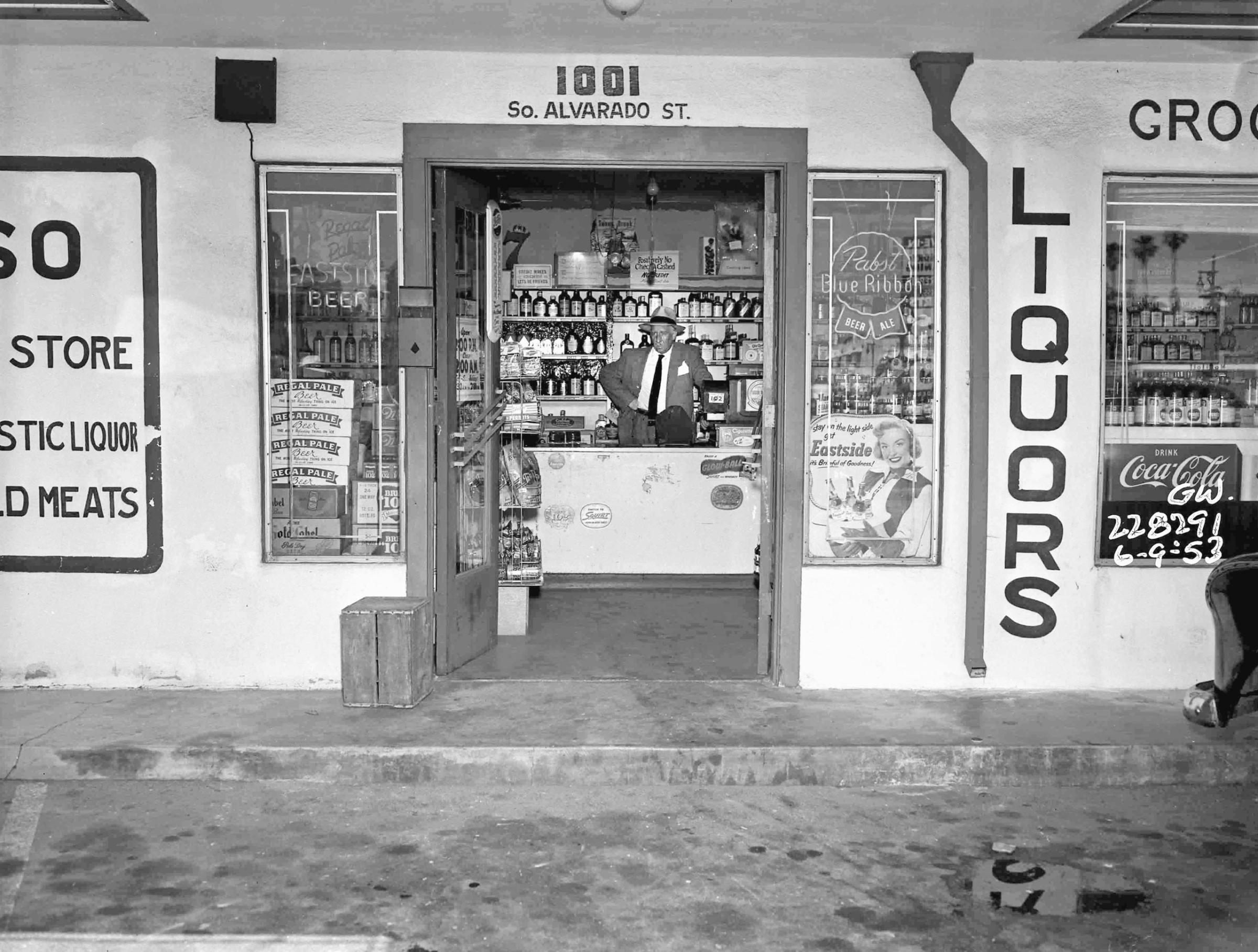

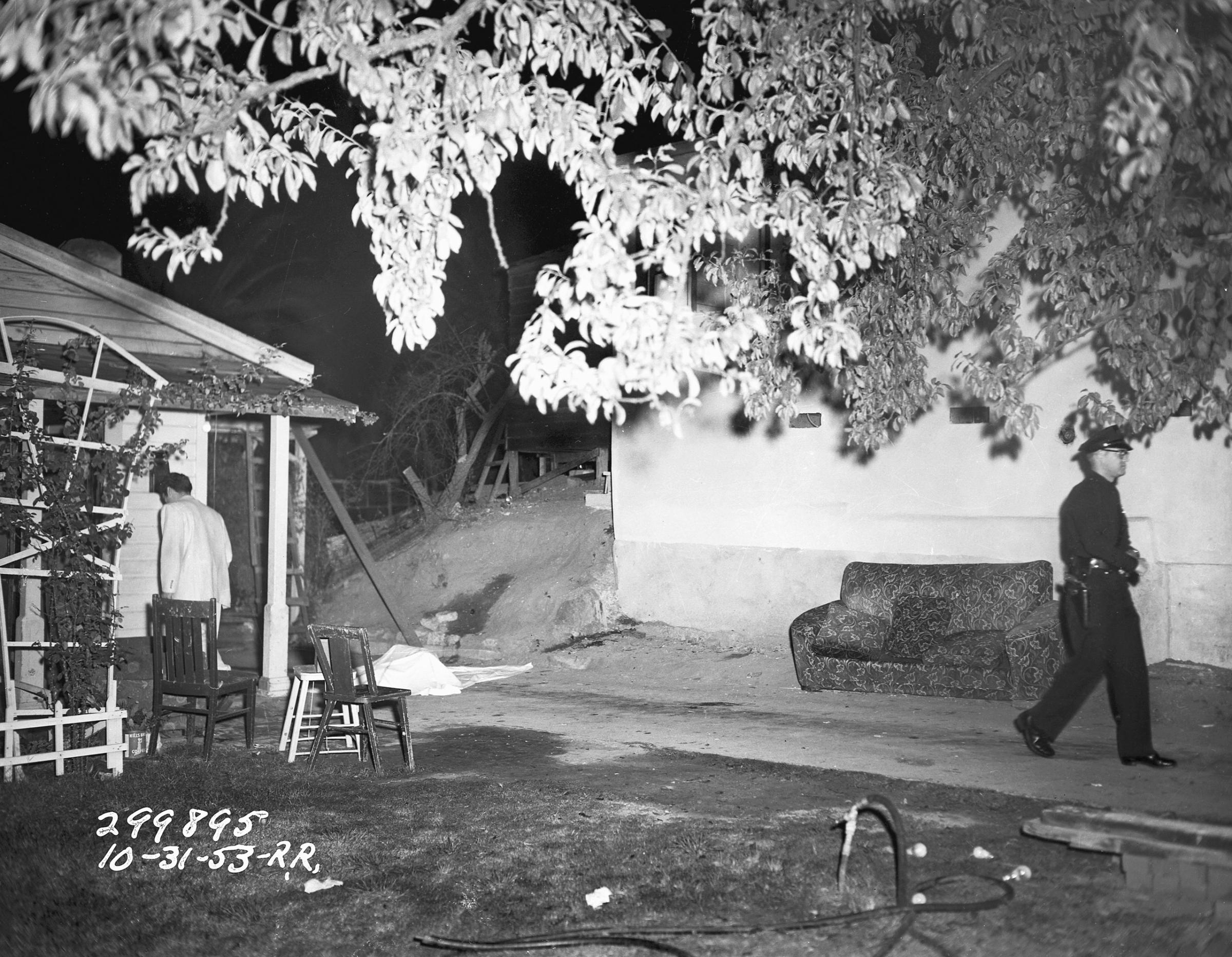

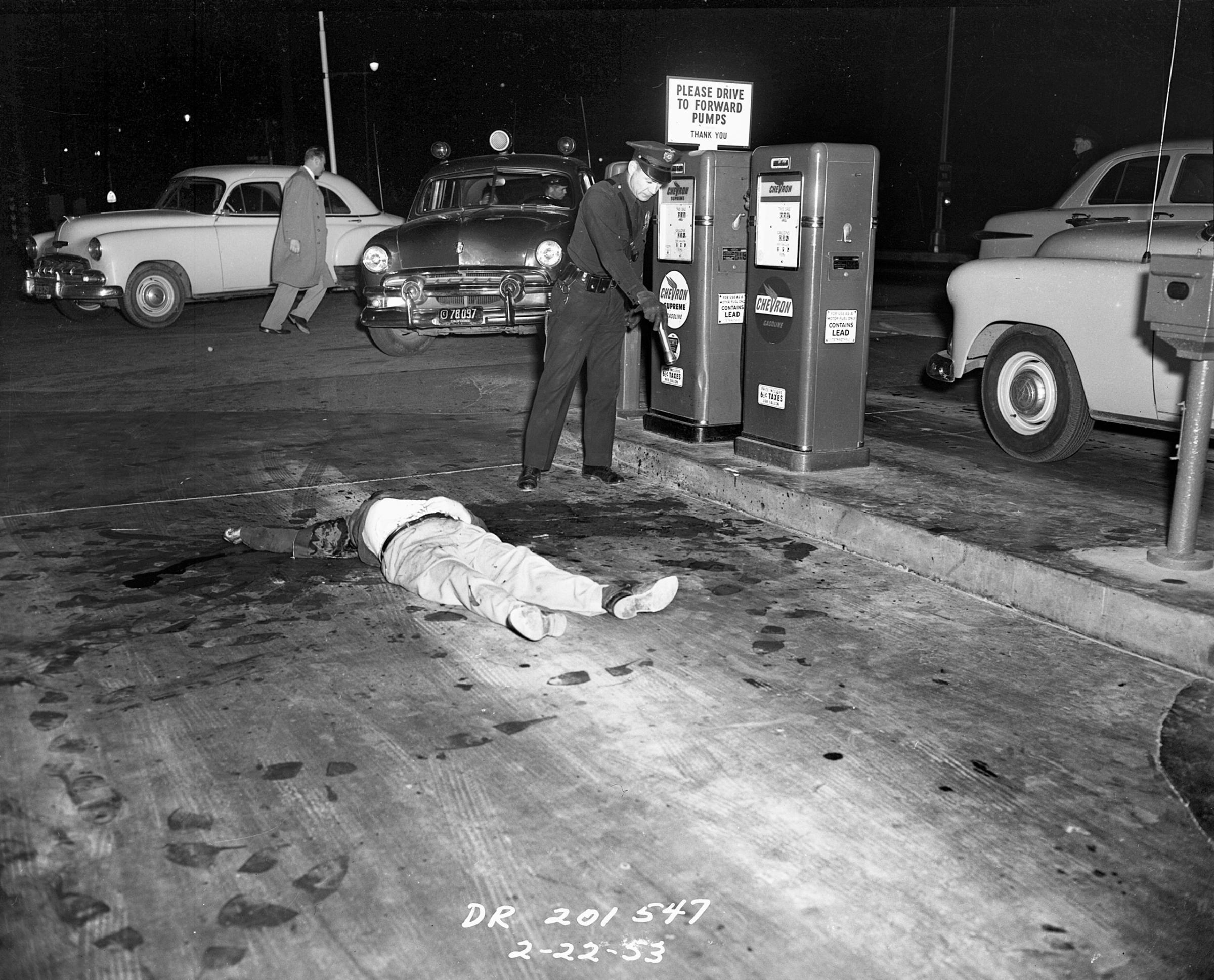

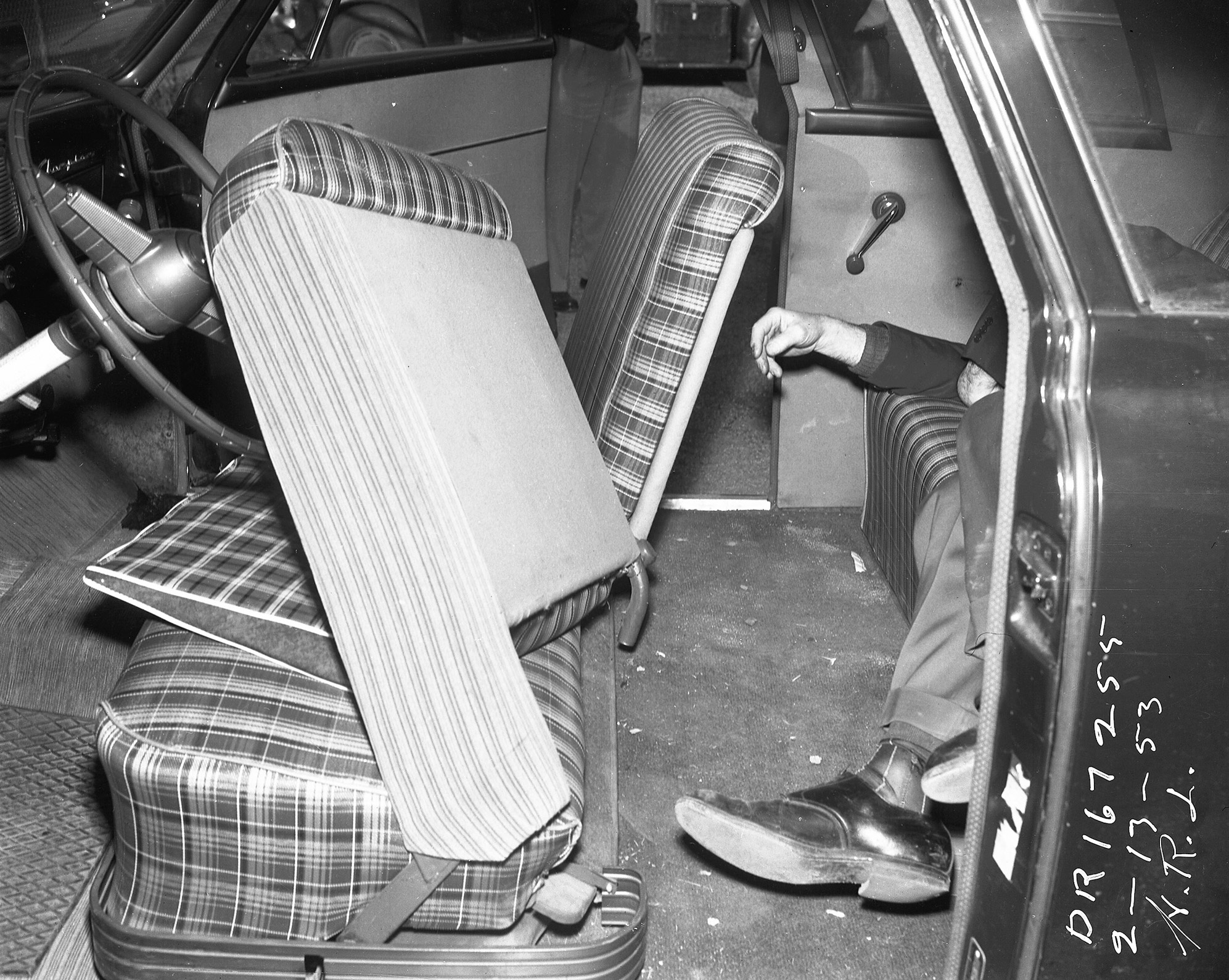

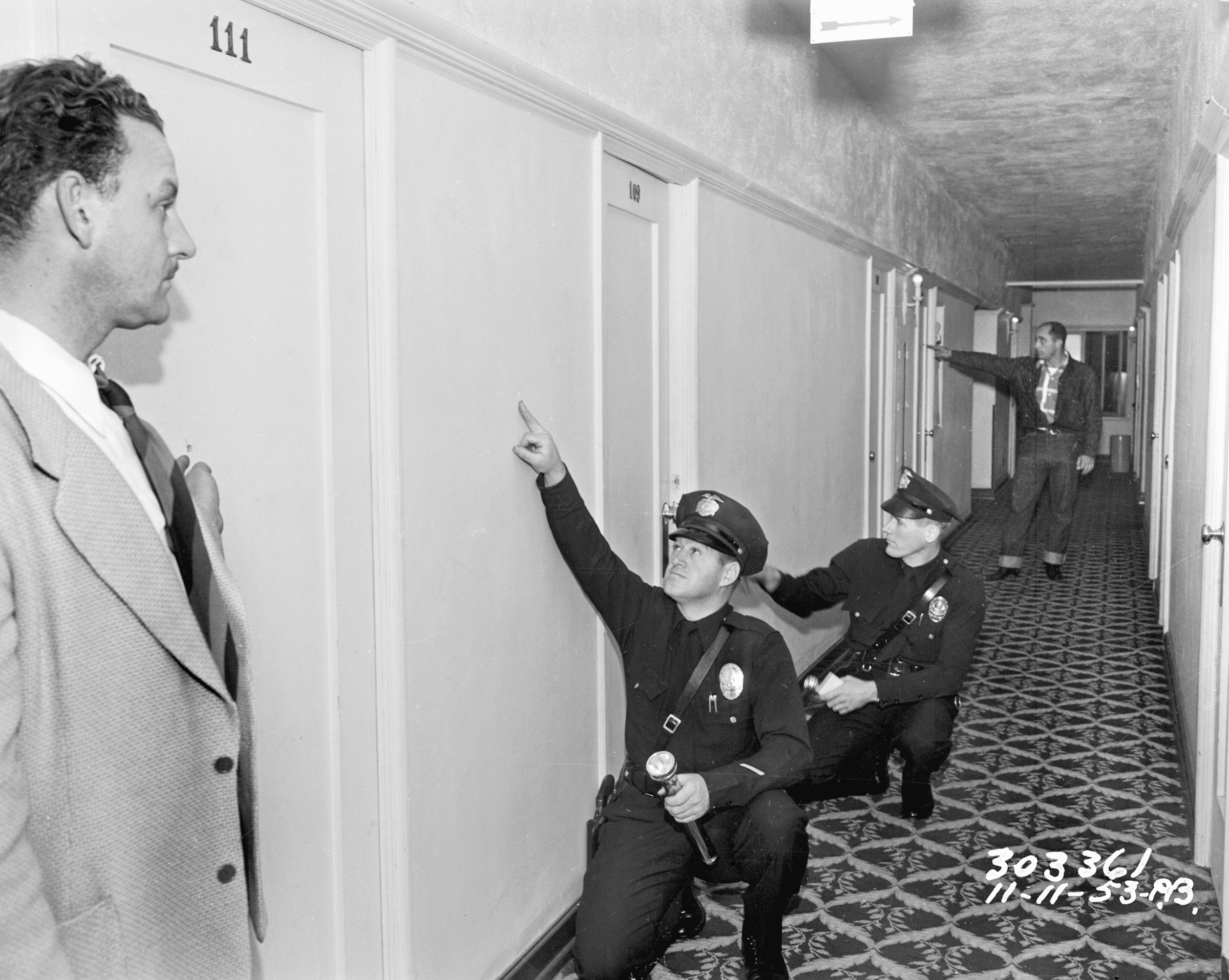

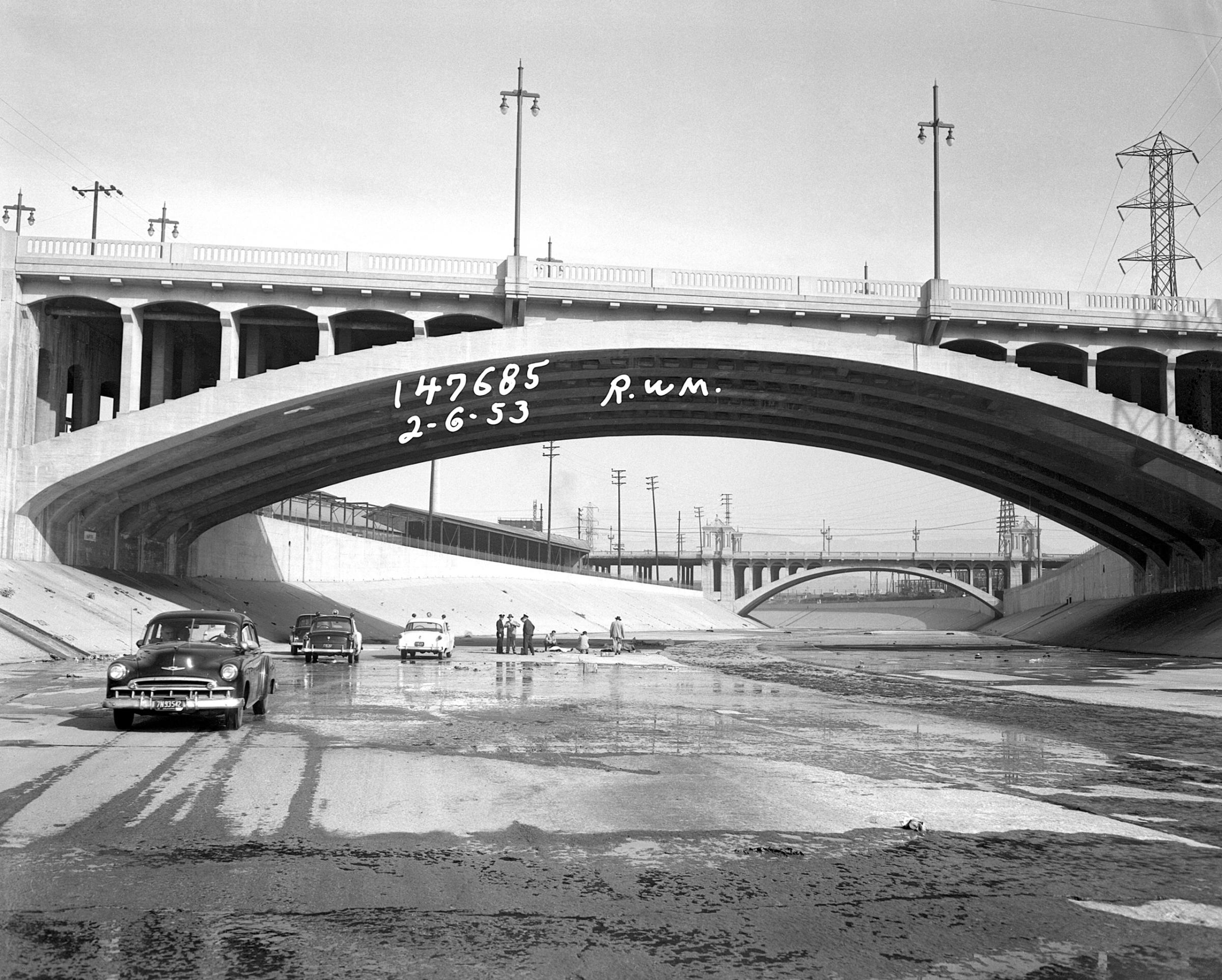

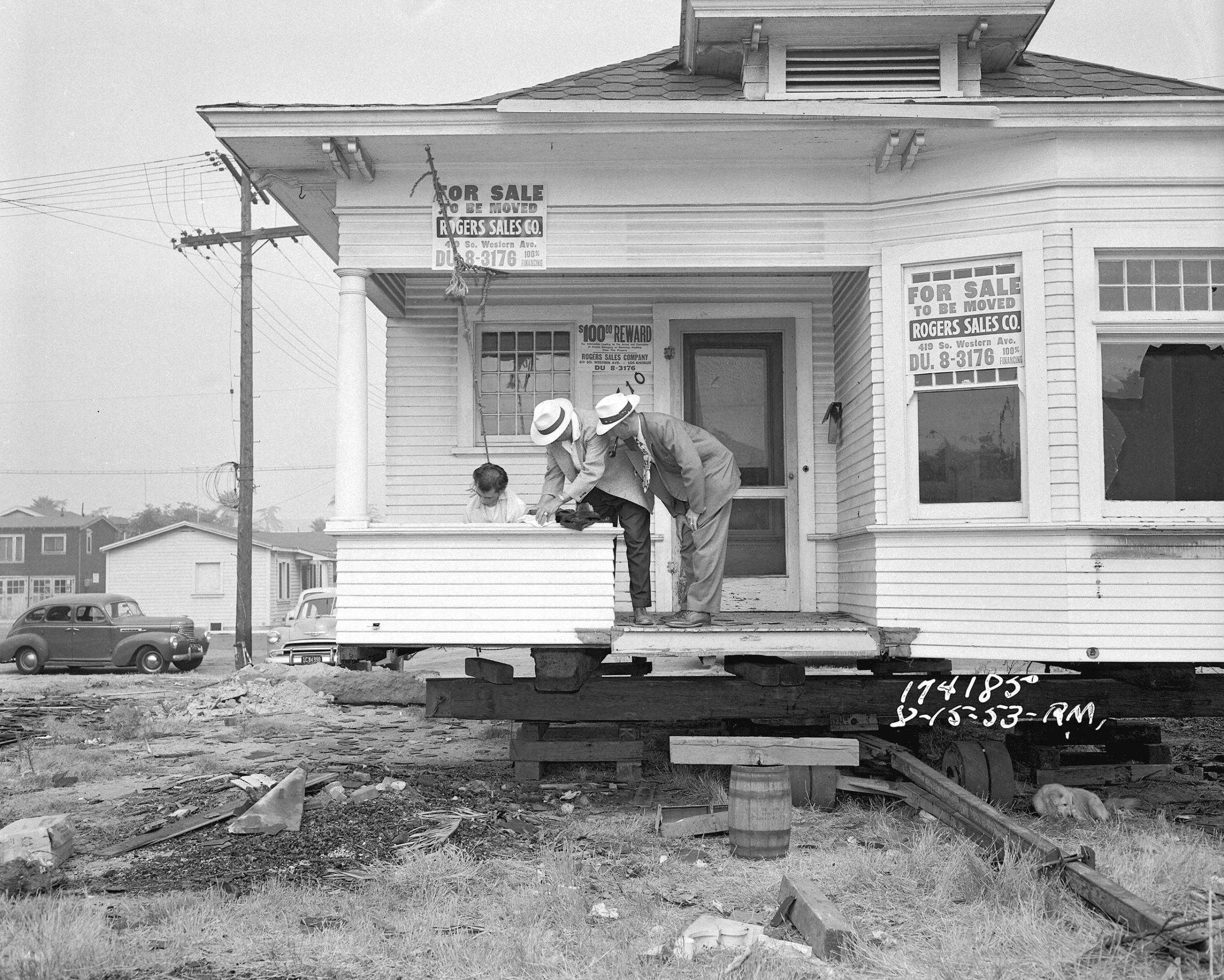

It was 1953. Eisenhower was in the white house. The New York Yankees won the World Series for the fifth year consecutively. The theme music for the television series, “Dragnet,” rose to the top of the Billboard charts. It was also the year that Los Angeles had a record number of homicides—and more than twice as many suicides.

In the new book, “LAPD ’53,” crime and historical fiction author, James Ellroy and Executive Director of the Los Angeles Police Museum, Glynn Martin, take readers on a photographic tour of the city’s violent past. The eighty-five duotone photos that made the final cut are representative of a day in the life of America’s most provocative police agency.

“There’s no city with a police force quite as controversial, ambiguously defined and progressive as the LAPD,” Ellroy told TIME. “Geography is destiny. I was born in LA, the film noir epicenter, in 1948. I also grew up during the film noir era, which existed from 1945-1960. This brings up the question, which came first? Was film noir itself influenced by archival police photos or did film noir in its dark chiaroscuro style of lighting influence police photography?”

If anyone knows the answer to this question, it’s Ellroy, who has published 14 novels, two memoirs, and three books of collected novellas, short stories and nonfiction. He also collaborated with former Chief Bratton on the book, “Scene of the Crime: Photographs from the LAPD Archive,” (October 2004).

In every sense, “LAPD ‘53” is the true account of the universe he created for his L.A. Quartet novels, which include: “The Black Dahlia,” “The Big Nowhere,” “L.A. Confidential” and “White Jazz.” These stories take place in Los Angeles from 1946 to 1958. Because of his epic crime stories and personal appreciation for the LAPD, Ellroy received the Jack Webb Award on October 15, 2005 at the police department’s 12th annual awards dinner saluting strength and inspiration. It was then that he and Martin first met and developed their close friendship.

“This project is all because of the generosity and philanthropy of James Ellroy,” said Martin, also a retired LAPD Sergeant, who wrote the introduction and acknowledgments for the book. “James has been a great supporter of the LAPD and a friend of the police museum for a long time.” At one of the meetings he and Ellroy had with current Chief of Police, Charlie Beck, the bestselling author proposed a publishing program for the museum, which included donating his own time, talent and earnings toward this goal. Once approved, Martin and his team of volunteers enthusiastically began digging through decades of 4X5 photographic negatives. “This didn’t start out as a collection of photos from 1953,” Martin said. Both he and Ellroy expected that they would need a sampling from several decades in order to have enough photos for a book. “We sorted through negatives from the 1920s to the 1960s.”

“Once Glynn and I studied the photos with our book team at the museum, we made the determination that everything we wanted fell under the calendar year of 1953,” Ellroy said. “We were astounded by the diversity of the crimes. There’s a lot of murder and a disproportionate amount of suicide, but what unifies it all is the level of artistry of the photographs themselves. These photographers were sworn police officers carrying a gun and a Speed Graphic camera. They were also constrained by the law. They couldn’t go in and rearrange the body for maximum dramatic impact.”

Nikolas Charles is a journalist, music critic and photographer based in Los Angeles.

Liz Ronk, who edited this photo essay, is a photo editor at LIFE.

More Must-Reads from TIME

- Cybersecurity Experts Are Sounding the Alarm on DOGE

- Meet the 2025 Women of the Year

- The Harsh Truth About Disability Inclusion

- Why Do More Young Adults Have Cancer?

- Colman Domingo Leads With Radical Love

- How to Get Better at Doing Things Alone

- Michelle Zauner Stares Down the Darkness

Contact us at letters@time.com