Motherhood, like yoga or eating, is not supposed to be a competitive sport. But some people can’t help themselves, and just as with yoga or eating, among certain types of humans, it can become quite a contest.

Take the moms of the upper east side of Manhattan, one of America’s—if not the world’s—most well-provisioned regions. The moms there have everything a parent could want for their offspring: the most delectable food, the most meticulous childcare and education and the most adorable woolen toddler clothes with French names.

They even have amenities other parents never get around to wanting, like a pre-labor blowout, an annual bonus for being a wife, a closet just for handbags and a person who organizes things when said bonus brings forth more handbags than closet.

You’d think, with all this, those moms would be super chill with their lot. But, according to a book out on June 2, they’re not. They’re competitive and fearful and ruthlessly hierarchical. “Being a mommy here is a cut-throat, high-stakes career, stressful and anxiety producing,” writes Wednesday Martin, a former player on the Upper East Side parenting circuit. Now she’s a commentator, kind of like John McEnroe, only the sport is high-end mothering.

At least that’s the sell. Martin’s training is in anthropology and in Primates of Park Avenue, she uses her education to try to bring insights into the behavior of insanely wealthy moms. She identifies “alloparents” (nannies); faces down women who, in the manner of aggressive chimpanzees, “charge” lesser females on the sidewalk (literally barge past them and force them to give way) and analyzes a condition known as “ecological release,” which results when natural cycles and rhythms are no longer an issue—the families of this region are immune to such vagaries as seasons or drought or grey hair.

But, unlike most observers of primate behavior, Martin scrutinizes all this not as an outsider. She’s right in the 10021 zipcode. It’s as if she is writing about gorillas while married to a silverback (her husband, Joel Moser, is the CEO of a finance company) and chewing on stems and bamboo shoots. She’s gone native. (Or went; the Martin-Mosers moved to another part of town after about six years.)

A primatologist’s take on the most moneyed of the Great Apes is a pretty irresistible premise for a memoir. The habits of well-provisioned humans have always been of interest to the other 99% of the species, partly because bystanders to displays of wealth, as to any spectacle, always suspect that in the same circumstances they could do so much better.

Subscribe to TIME’s weekly parenting newsletter, with stories from all over the web, tips and more…

So what happens when there’s no competition for resources? People manufacture needs to compete for. Thus, getting a 2-year-old into the right pre-school becomes for these mothers an Iditarod of phone-calls, interviews and favor-trading. Organizing playdates is akin, in Martin’s telling to getting a home loan with suspect credit. Her kid only succeeds in landing any, she says, because his mom “happens” to charm an alpha dad. Martin spends about an eighth of book detailing her long, arduous quest—full of setbacks and heartstopping turns of fortune!— for a certain handbag.

The book has caused something of a stir. First, there’s the revelation that some women in this world get a so-called wife bonus: an annuity given to a female spouse by her husband for meeting certain benchmarks. Martin uses this act of largesse as an example of the asymmetrical power between the two halves of the marriage, but the idea was seized upon in the public sphere as the most deliciously repellent kind of excess, a big bag of bills for doing things all moms do everywhere.

In response to the uproar, one brave woman even stepped up to explain why the wife bonus made her feel like a good feminist, because staying at home looking after the kids is as important to her family as what her oil-company husband does. (She apparently did not feel like a bad feminist for spending much of it on shoes.)

But the wife bonus, like so many of our outrages, turns out really just to be a new name for something that surprises no-one—guys with a lot of money telling their wives how much they can spend on things that are not strictly part of the household expenses: shoes, a charity, whatever.

Are there real discoveries in the book? Some. I lost faith in some of Martin’s science after a passage that compared pregnant women to kangaroos having to decide whether to eject their joeys (offspring) when running from predators. Apart from humans, kangaroos don’t really have predators. And they definitely don’t run.

But what the book does make clear is that we are, as a species, prone to fear. Even if resources are plentiful, we humans fear scarcity. Even if opportunities and promise are obvious, we fear failure. Even if our children have never had a need or a whim unanswered, we fear we are not doing enough. And that fear makes us forget that we are stronger as a group. Our gains and losses are better shared than fought over. When Martin’s family suffers a sad blow, her erstwhile rivals surround her and lessen the impact. Of course.

Perhaps that’s why Martin’s book, eventually, reads as a pretty gentle and generous analysis of her former neighbors and their mothering abilities. Another thing that’s not supposed to be a competitive sport: memoir writing.

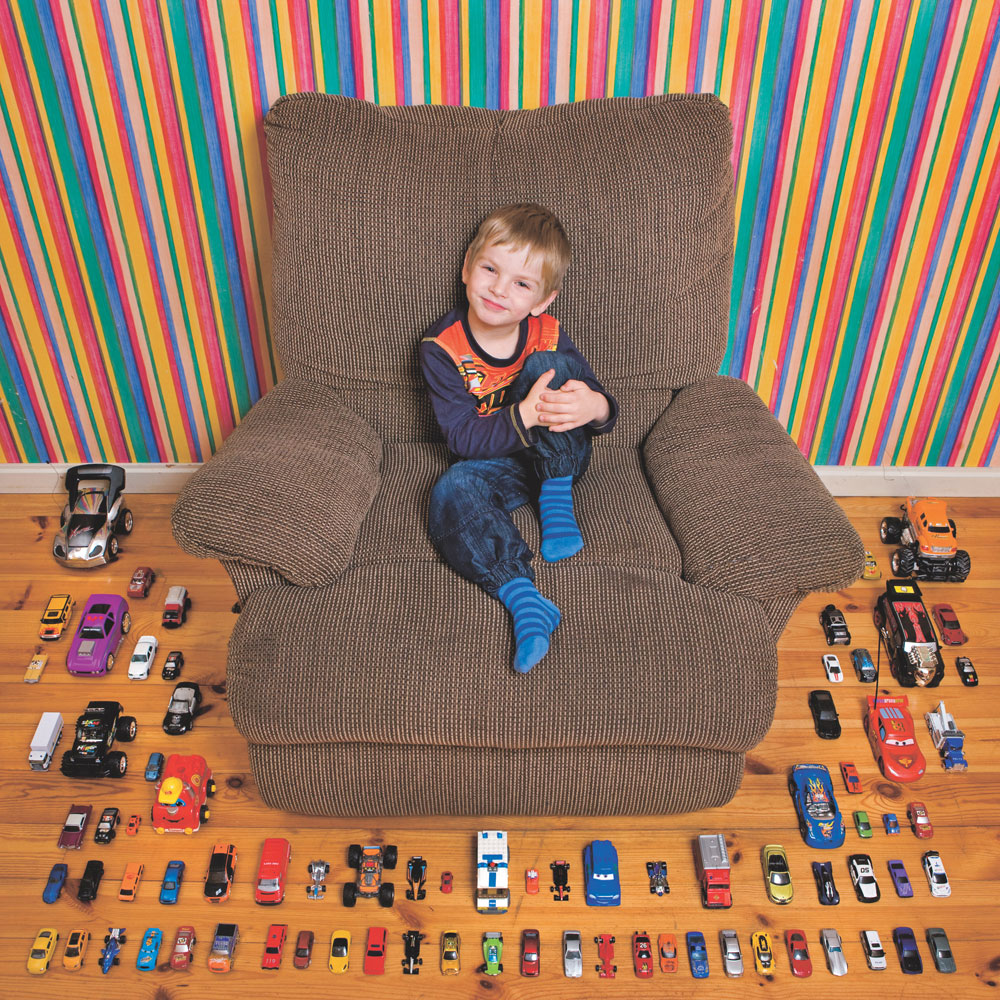

These Kids Want to Show You Their Favorite Toys

Read next: 19 Secrets Your Millionaire Neighbor Won’t Tell You

More Must-Reads from TIME

- Why Trump’s Message Worked on Latino Men

- What Trump’s Win Could Mean for Housing

- The 100 Must-Read Books of 2024

- Sleep Doctors Share the 1 Tip That’s Changed Their Lives

- Column: Let’s Bring Back Romance

- What It’s Like to Have Long COVID As a Kid

- FX’s Say Nothing Is the Must-Watch Political Thriller of 2024

- Merle Bombardieri Is Helping People Make the Baby Decision

Contact us at letters@time.com