This post is in partnership with the History News Network, the website that puts the news into historical perspective. The article below was originally published at HNN.

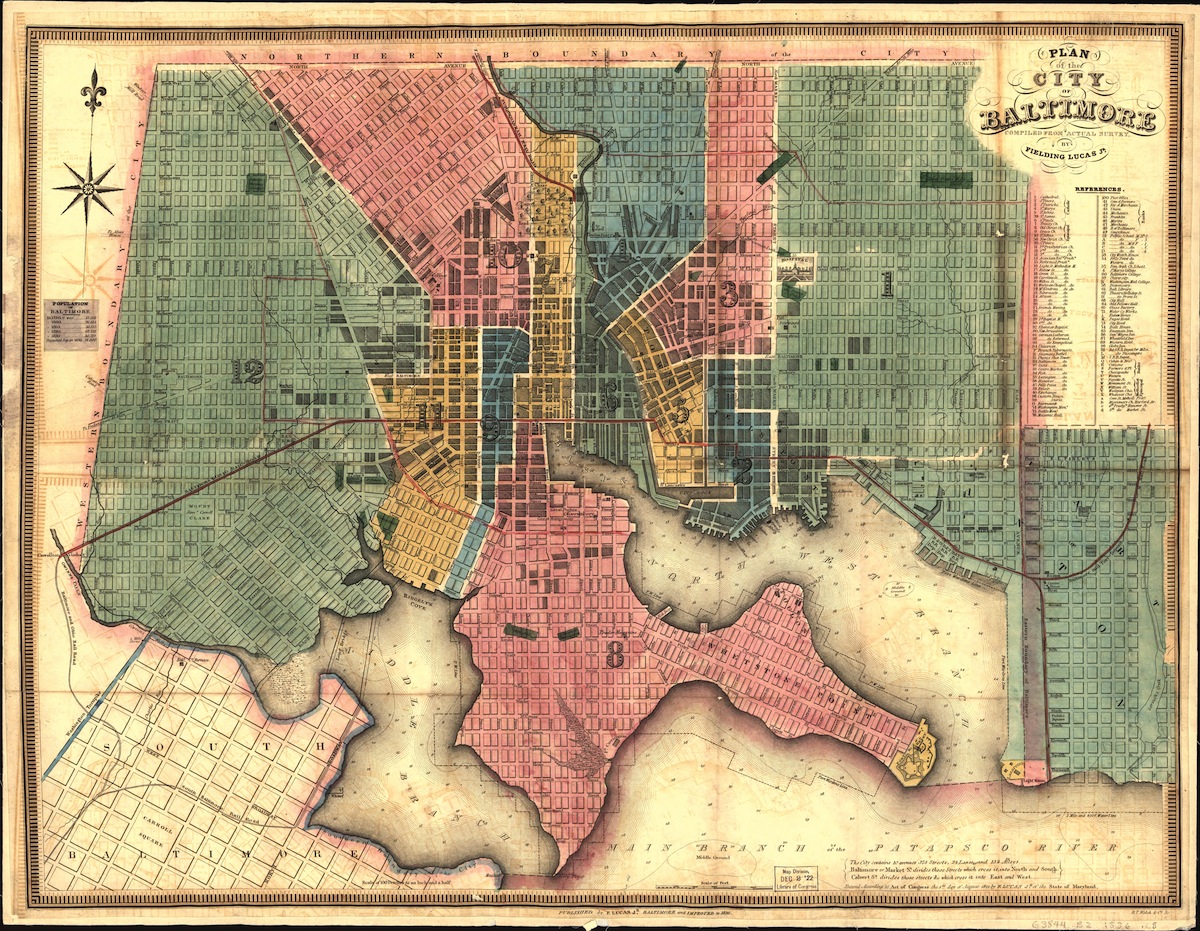

Recent Baltimore protests over the police homicide of Freddie Gray were about much more than the killing of a young black man. The legacy of slavery is deep in a city many consider to be outside the South. “The Monumental City” as it was known in the 1820s was at the headwaters of American human trafficking. That traffic’s structural violence turned African American sons and daughters, wives and fathers into human products. One in seven enslaved African Americans was forced across state lines in the following decade. In Baltimore black people were jailed, sold, and shipped in the bellies of merchant vessels. Most were stolen from families by slave traders. Austin Woolfolk was a mastermind of the market.

Just nineteen when he arrived in Baltimore in 1815, the tall, athletic slave trader operated out of city taverns, handing banknotes to slaveholders thirsty for liquid assets. Woolfolk came up in Tennessee, served in that state’s militia during the War of 1812 and participated in the Battle of New Orleans. There he saw the fortunes to be made on the backs of African-descended countrymen.

The foreign slave trade was closed in 1808 yet planters demanded young bound workers for their canebrakes and cotton fields. As demand rose in the Deep South for bondspersons bound away from Eastern Seaboard homes, slave prices in New Orleans reached roughly twice what they were in Maryland. Yet there wasn’t yet an interregional exchange.

Woolfolk was an entrepreneur with a gift for imagining a market before it existed and then ushering it into being. His main innovation was advertising in rapidly-growing daily newspapers. Like cash for cars or gold today, “CASH FOR NEGROES” was his tagline. Woolfolk soon became a brand.

Early on he used the Baltimore City Jail to warehouse captives until shackling them together and force-marching them to Georgia. But as cotton became the nation’s biggest export commodity in the 1820s, Woolfolk built his own jail and booked space aboard merchant ships. He built a reputation in New Orleans, site of the Deep South’s largest slave market.

Woolfolk’s brothers and other relatives arrived in Maryland to cash in on the profits. Woolfolk-allied traders set up purchasing agencies in Annapolis, Easton, and Washington D.C. By 1821 Austin Woolfolk’s Baltimore headquarters included a whitewashed house and private jail located on West Pratt Street at the intersection of what is today Martin Luther King Jr. Boulevard (any archaeological remains are buried under a divided highway).

It was a far-flung enterprise. Woolfolk’s uncle, John Woolfolk, set up in New Orleans and Natchez, running a sales agency, selling people, acting like a bank, and remitting the tens of thousands of dollars (millions in today’s money) that sustained a supply chain in captives. The combination of newspaper advertising, financiering, shipping, and an elaborate corporate form (for the day) gave the Woolfolks competitive advantages that drove rivals out of the market.

Some protested. “Cash for blood” screamed Baltimore’s Niles’ Weekly Register in 1821. Anti-slavery Quakers arrived at Fell’s Point to inspect ships in which Woolfolk’s captives were consigned. Such ships were part of an architecture of oppression, which seamlessly combined traffic in human beings with trade in commodities like flour, wine, and manufactured goods.

Woolfolk brushed aside such protests and quickly became a business insider. Shippers wanted his goods. And officials smiled on a businessman they considered one of them. Yet his human wares did not go to market quietly. In 1826 Woolfolk consigned captives including Maryland native William Bowser to the merchant schooner Decatur. On the passage to New Orleans, Bowser and two other captives rose up, threw the captain and a crew member overboard, and took over the ship. But their rebellion was cut short when the captain of a whaler sent armed sailors to overpower the Decatur rebels.

Bowser was tried, convicted, and hanged in New York City for murder. Abolitionist editor Benjamin Lundy covered the proceedings for his Baltimore newspaper The Genius of Universal Emancipation, reporting that Bowser forgave Woolfolk while walking to the Ellis Island gallows as the slave trader cursed him. When Lundy ran into Woolfolk near the Baltimore Post Office the following winter, the slave trader attacked the abolitionist for smearing him. Woolfolk was seven inches taller and as many years younger than the Quaker editor, who put up no resistance to being stomped on the head.

When Woolfolk was tried for the assault, however, Baltimore Judge Nicholas Brice sympathized with the slave trader, contending that “the trade itself was beneficial to the state, as it removed a great many rogues and vagabonds who were a nuisance.” Lundy, he said, deserved his beating, “and but for the strict letter of the law, the court would not fine Woolfolk any thing.” He paid a dollar plus court costs.

Another young abolitionist arrived in Baltimore to contest Woolfolk’s traffic. In his early twenties, William Lloyd Garrison called Woolfolk out, exposed his business as the moral equivalent of kidnapping. But his activism agitated authorities. In 1830 Maryland tried Garrison for libeling a shipmaster whose vessel carried nearly ninety captives to Louisiana. Again, Judge Brice presided. Garrison was convicted and sentenced to jail, where he was radicalized.

By then Woolfolk was transitioning from trader to executive, moving to Louisiana where he owned considerable real estate including an Iberville Parish plantation house built atop an Indian mound. Slaving was a young man’s trade, but he continued in the business until his death in 1847, leaving a fortune to his heirs. Today the economic status value of Woolfolk’s estate would be $201 million.

To black people in Baltimore and the surrounding countryside, the name Austin Woolfolk conjured a nightmare of shackles and sales, bondage in faraway fields, disappeared relatives, and the dissolution of ties of family and friendships. As a child enslaved in Baltimore, Frederick Douglass recalled “In the deep, still darkness of midnight, I have been often aroused by the dead, heavy footsteps and the piteous cries of the chained gangs that passed our door” driven to the docks by Woolfolk.

Slavery was big business, which enriched slaveholders and externalized the towering human costs onto African Americans. In 1830, the aggregate value of United States slaves was about $577 million. The economic power value in 2014 dollars would be $9.84 trillion (56 percent of 2014 GDP). And Woolfolk’s firm helped orchestrate a huge transfer of borrowed wealth from the lower South to the upper South as it funneled thousands of captives south by southwest, to points of no return, leaving a legacy of white supremacy and black servitude that equated black bodies with disposable property.

Calvin Schermerhorn teaches history in Arizona State University’s School of Historical, Philosophical, and Religious Studies and is author of the new book “The Business of Slavery and the Rise of American Capitalism, 1815-1860” (Yale, 2015). He is also the author of “Money over Mastery, Family over Freedom: Slavery in the Antebellum Upper South” (Johns Hopkins, 2011) and co-edited “Rambles of a Runaway from Southern Slavery,” by Henry Goings. His research focuses on slavery, capitalism, and human trafficking.

More Must-Reads from TIME

- Cybersecurity Experts Are Sounding the Alarm on DOGE

- Meet the 2025 Women of the Year

- The Harsh Truth About Disability Inclusion

- Why Do More Young Adults Have Cancer?

- Colman Domingo Leads With Radical Love

- How to Get Better at Doing Things Alone

- Michelle Zauner Stares Down the Darkness

Contact us at letters@time.com