South Asian-Americans, whose forebears immigrated from countries like India or Pakistan, have now won the Scripps National Spelling Bee eight years in a row. At one point in the 2015 final, six of the remaining seven spellers were of that ethnicity, and in the end there were two: co-champions Vanya Shivashankar and Gokul Venkatachalam. That means that out of the last 16 years, spellers of South-Asian origin have lost only four competitions. And one Northwestern academic says it’s not a coincidence.

Shalini Shankar, an associate professor of anthropology and Asian-American studies, spent this week with the 283 elite spellers who qualified for the bee in National Harbor, Md., continuing her research into what, exactly, might have produced this string of success. TIME spoke with Shankar about her interviews with parents, the kids’ intense preparation and how immigrant culture might lead to dominance in “brain sports.” (Hint: It doesn’t hurt that there is a spelling bee circuit exclusively for spellers of South-Asian descent.)

Who exactly are we talking about when we talk about top spellers in South Asian cultures?

Primarily India and Pakistan and Bangladesh are the countries that appear to have a lot of spellers. And when you look at South Asians in the South Asian spelling bee, it’s a range across those three countries. Occasionally from Sri Lanka as well. But once you get down to the finals or the championship level, it tends to be more spellers just from India. So Indian-Americans. Usually they are second generation. They were born in the United States to parents who are first generation Indian immigrants.

Is there a chance the string of wins by South Asian-Americans is a coincidence?

I think we can safely say it’s not a coincidence. I hesitate to call it dominance, only because it sounds like something premeditated or strategized. These kids come from families where their parents are really well educated, many of them, and their parents really emphasize education and certain types of extracurricular activities. Combined with that, they seem to have a real love of words and language and their parents foster that.

What kind of extracurricular activities are we talking about?

The parents spend a lot of their time and resources taking [their kids] to participate in what some of them describe as brain sports. So rather that going to travel baseball or travel soccer, they’re traveling this academic competition loop. Part of why you’re seeing their success on the rise is they’re in constant preparation mode for these various academic competitions. And there are several competitions that are exclusively for children of South Asian parentage. So they have more opportunities to do what they’re doing.

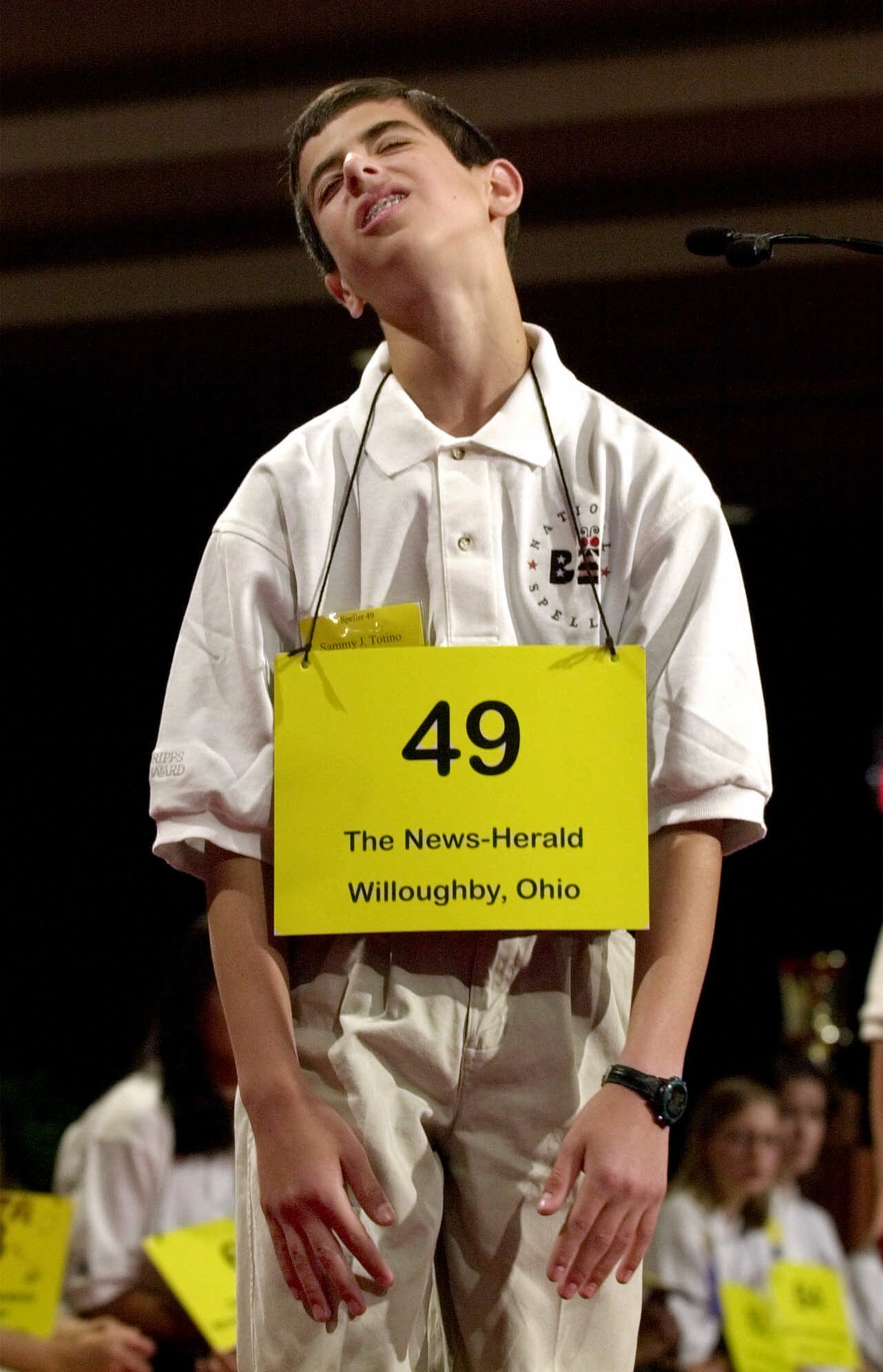

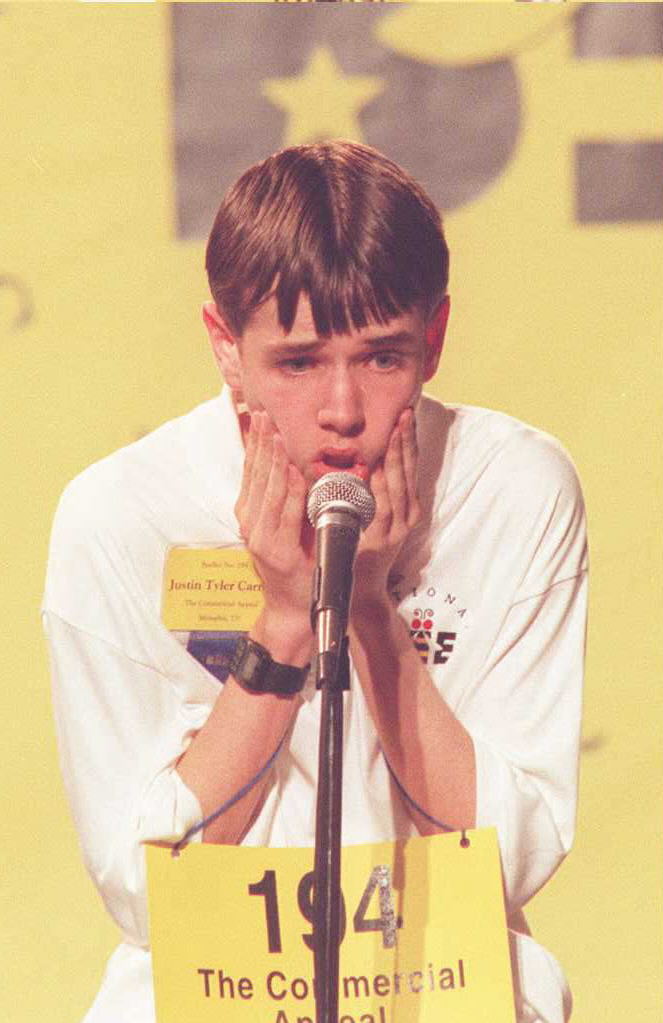

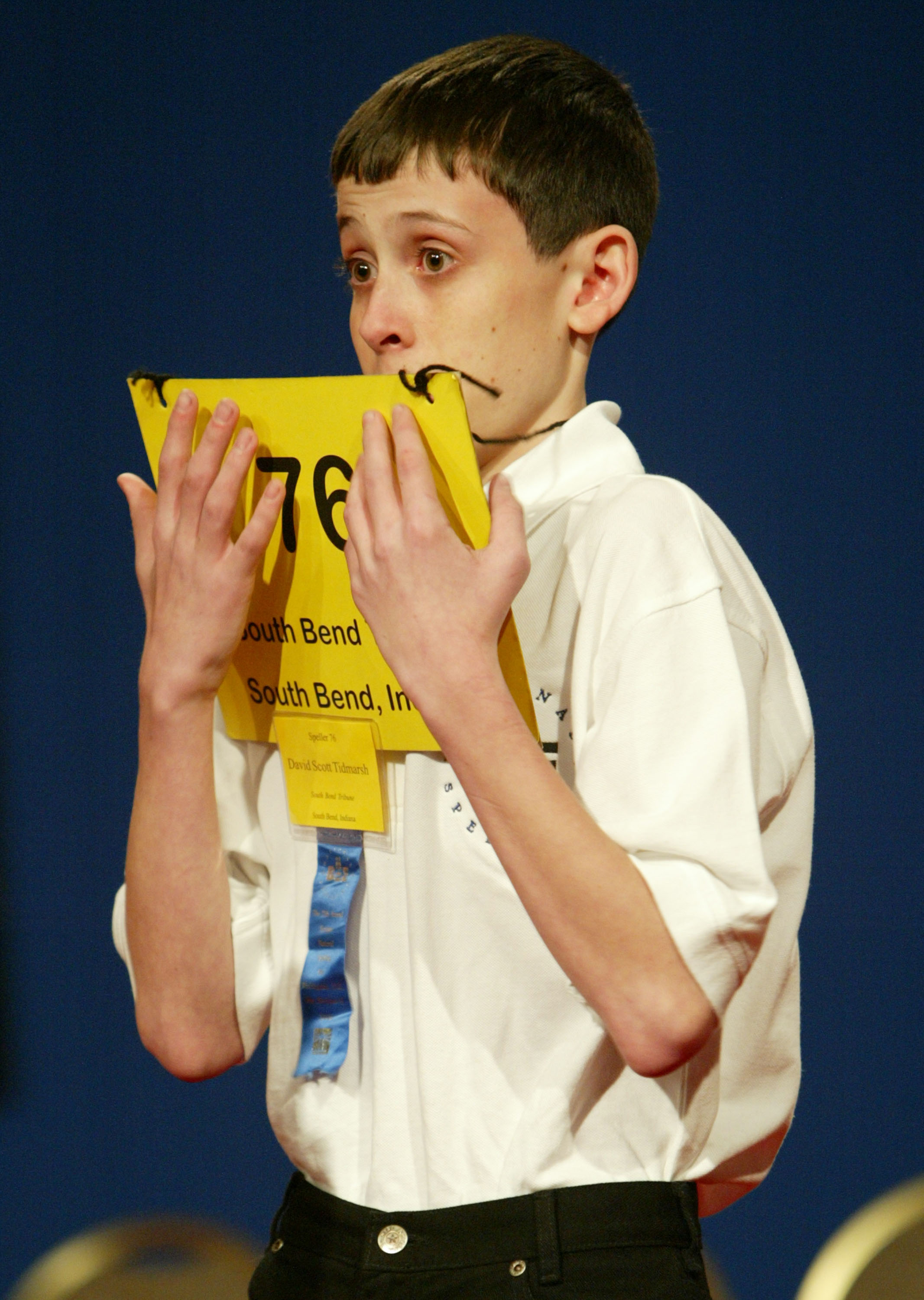

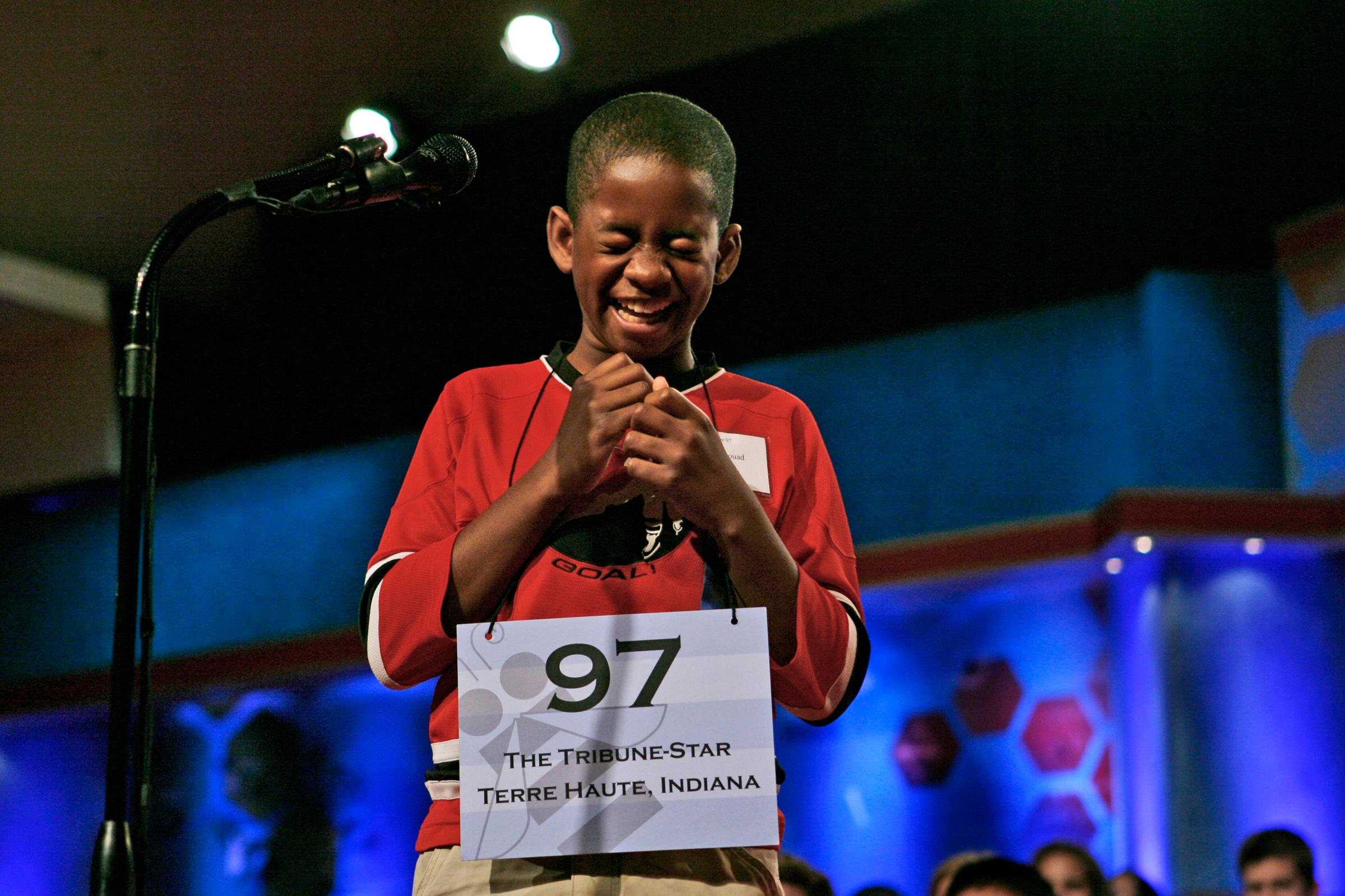

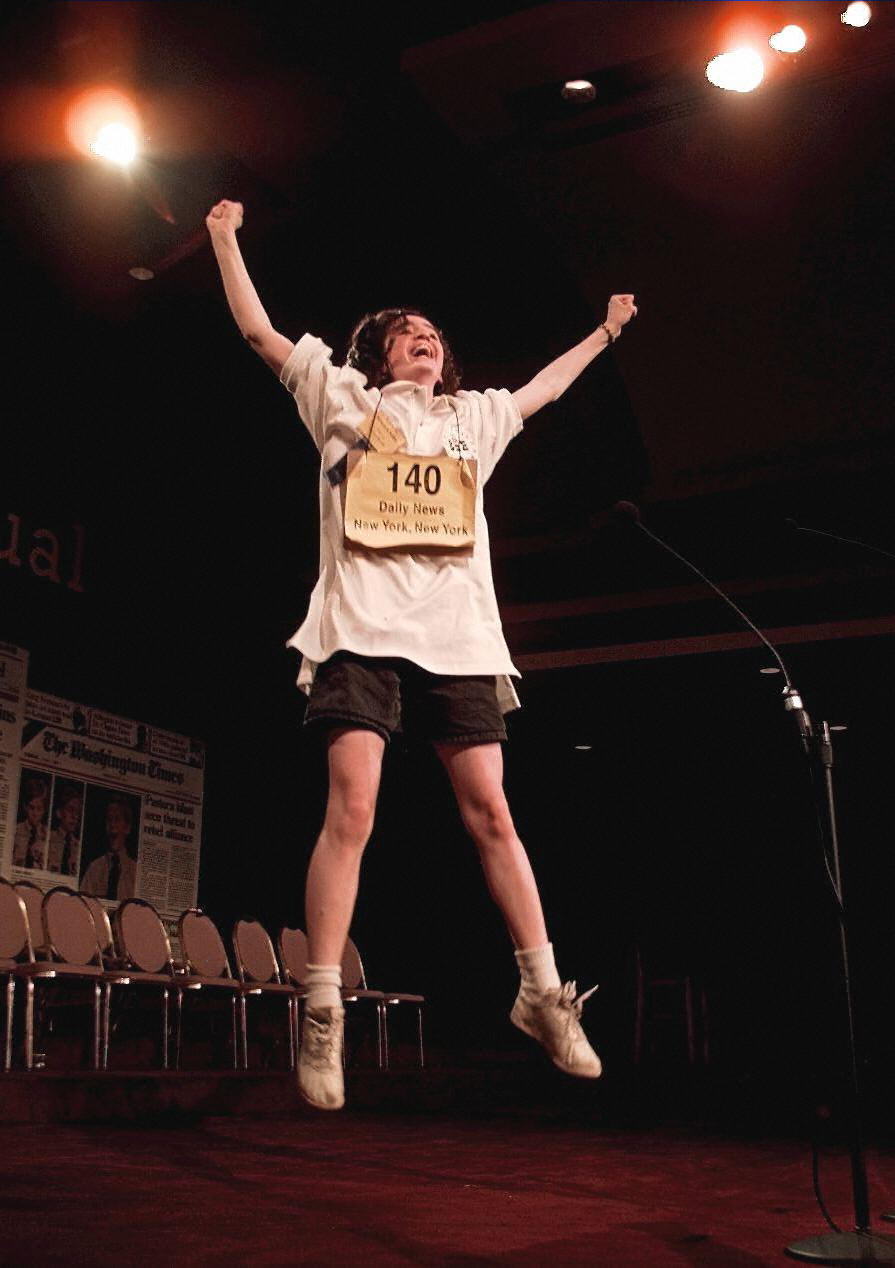

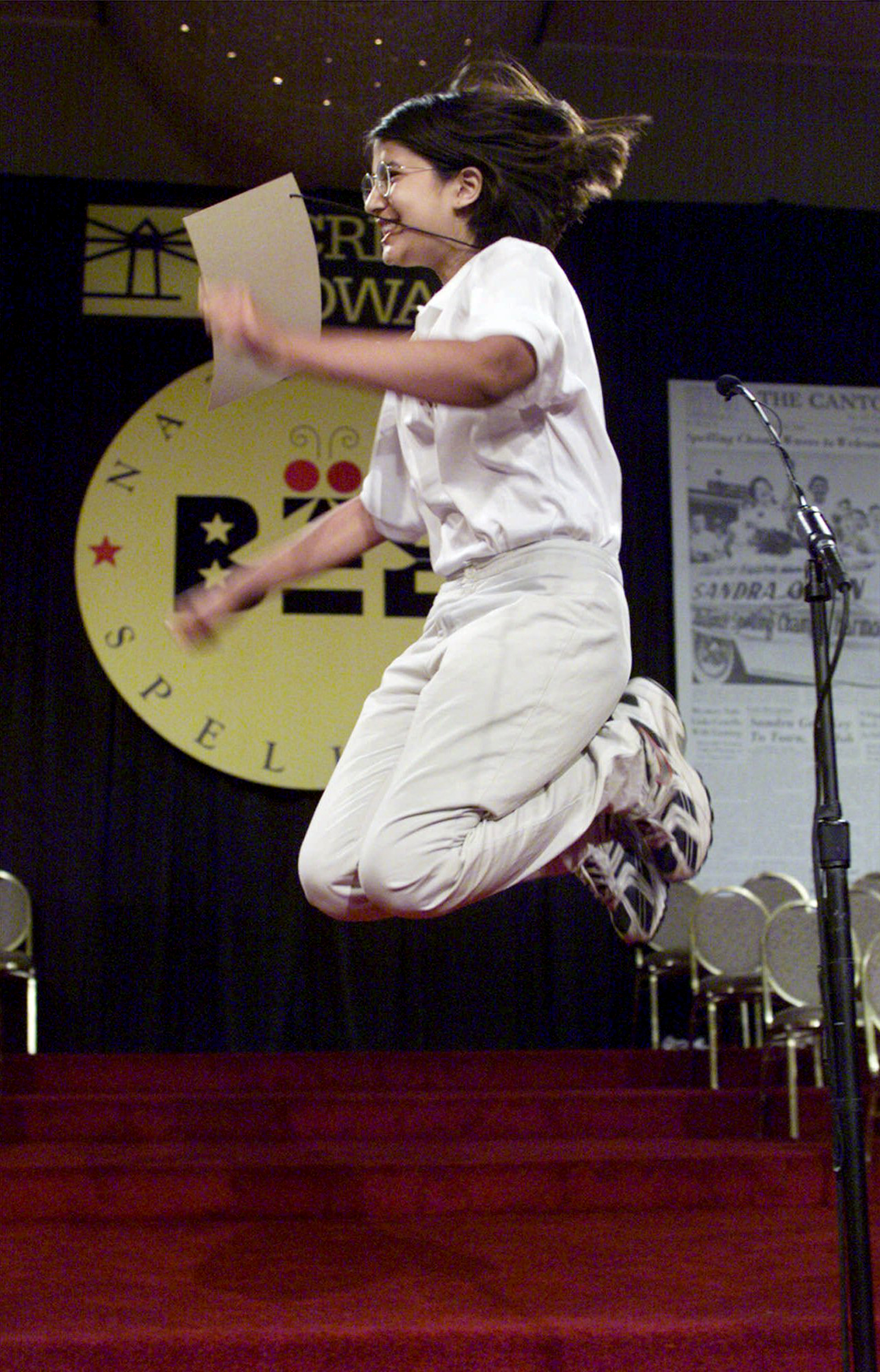

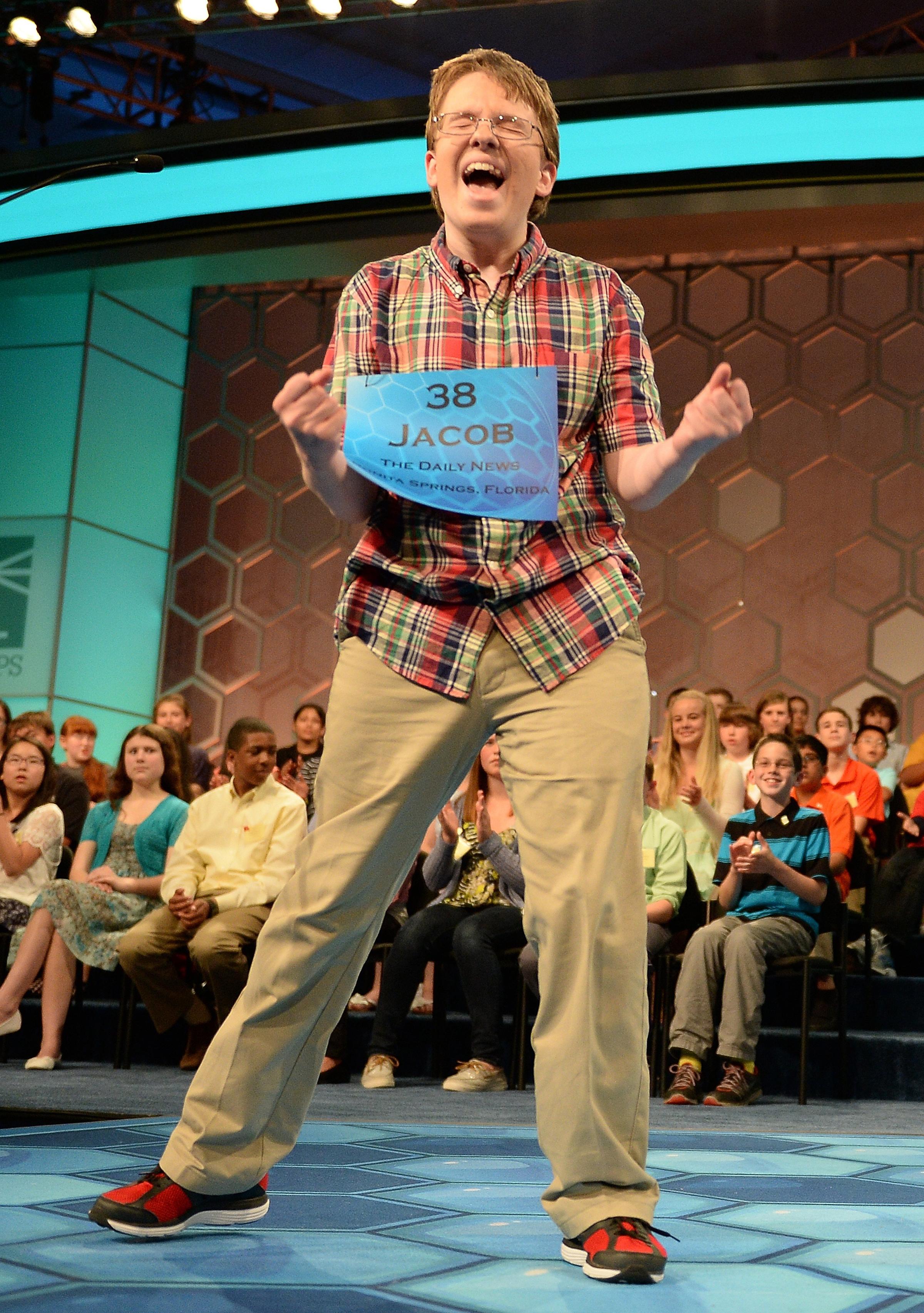

The Most Emotional Moments in National Spelling Bee History

If part of this is the parents spending money on the travel circuit, does income level come into play in explaining the phenomenon?

I can’t speak to income levels because I don’t have that data. But I can safely say there’s at least one professional parent in most of these families that have what they call elite spellers. So they’re certainly socially upwardly mobile families even if they may not be wealthy, per se.

How much have you found the kids are into this intense competition because their parents are pushing them, versus pursuing it themselves?

The parents are definitely facilitators to this process but they can’t actually produce champions. They can only enable their children to excel in this activity if they’re predisposed and dedicated to doing it themselves. But I don’t think that’s so different from spelling bee champions of any other race or ethnicity. Any time you see spellers who really are dedicated and they’re making it to the highest levels of competition at the national level, generally their parents have invested a tremendous amount of time and energy helping them.

But isn’t there something, even if it’s not Tiger-Mom tactics, like a value the parents are passing along about what kind of competition is worth winning?

I have some partially formed ideas about that. I’m still looking into it. Part of what I’m seeing is that there’s a lot of prestige in this community to winning something like a spelling bee or winning a geography bee or a math bee. And that is valued as much if not more than winning some sort of physical sport … These are very important bragging rights among South Asian-American communities. There’s some real status linked to it, that the kids feel too. The kids are really excited about the prospect of being on ESPN. They want to be on television.

Is there a more fundamental place in the culture that this value on academic prowess comes from, like what brought these immigrants to America?

Among the elite classes in India, both economically and socially elite, there’s a real emphasis on education and the use of education for social mobility. It’s not so different from other places in the world, but it’s certainly quite prevalent there. So I think that value is one that gets very magnified when you look at what Indian-American populations actually emigrated. It’s mostly professionals who immigrated post-1965. They are doctors or engineers or scientists, etcetera. So they are absolutely going to place a higher value on that than, say, other types of accomplishment. It doesn’t meant they downplay other types of accomplishments, but there’s an understood value of education that these contests jibe with very well.

What is it that drives these kids to dedicate themselves to spelling so intensely?

Unless you really love language and reading and words, it becomes very hard to care about preparing to the extent that one needs to for a spelling bee at this level. Kids who do this love words and they love thinking about words. They read the dictionary, among other things. And not all of them prepare to win. They set their own goals, like ‘I want to make it to Scripps’ or ‘I want to make it to the semi-finals’ or the finals and proportionately spend time preparing in whatever ways they think will allow them to attain those goals.

What is that preparation process like?

That process is usually every day, if not almost every day, they spend a few hours after school, after their homework, sometimes after their parents get home so they can quiz them. They spend several hours each weekend day preparing, maybe not year-round but certainly in the weeks and months leading up to the bee. Some of these spellers who compete in their school bees as well as these South Asian spelling bees, they don’t let too much time go by when they don’t have to be preparing for something. They’re kind of constantly keeping this fresh in their minds. So it’s an ongoing process for them, during the years in which they’re able to compete. And then suddenly it ends when they’re 14. It can be a very abrupt ending.

How do competitions like this affect the way we think about childhood?

If anything, the continuum of what childhood means is being expanded in productive ways to accommodate things that might have seemed extremely marginal or relegated to this untouchable nerd kind of activity. It’s something that has more mainstream cachet. I mean, being on ESPN is something very few kids get to do and these kids are very proud of participating in something that has such national recognition. It’s just expanding our ideas about what childhood means in ways that are keeping up with how the world is changing.

More Must-Reads from TIME

- Inside Elon Musk’s War on Washington

- Meet the 2025 Women of the Year

- Why Do More Young Adults Have Cancer?

- Colman Domingo Leads With Radical Love

- 11 New Books to Read in Februar

- How to Get Better at Doing Things Alone

- Cecily Strong on Goober the Clown

- Column: The Rise of America’s Broligarchy

Contact us at letters@time.com