National primary polls have never been so important—or so meaningless.

Nine months before the first votes are cast, these fickle numbers have become a make-or-break metric, determining whether a candidate will toil in obscurity or find a moment in national spotlight.

Fox News, the host of the first Republican debate, announced earlier this month that it will average the five most recent national polls that meet its standards in the week before on Aug. 6, and invite the top 10 finishers on stage. CNN announced that for the second debate in September, it would average national polls from two months prior, adding an average of early state polling as a tiebreaker.

Yet pollsters warn that the current methodology is ill-equipped to accurately measure such a sprawling field of potential candidates. The difference between the 9th and 13th place finishers in polls, where several candidates get less support than the margin of error, can be arbitrary. Candidates, meanwhile, have begun to complain that national polls mainly measure name identification, and national televised media exposure, ignoring the crucial role that early primary and caucus states play in the selection of the nominee.

“I think it’s strange that they aren’t taking early state polls, since that’s where candidates are placing their resources,” said an aide to one Republican candidate who does not yet qualify for the first debate. “In terms of the [Republican National Committee], they wanted to have this process, but I think it’s funny that they didn’t want the media picking candidates anymore except they are allowing media companies to do exactly that.”

“You can’t use polls to make very fine distinctions among candidates—such as who is in 10th place vs. 11th place,” says John Sides, a George Washington University Professor and co-founder of the popular political science blog Monkey Cage. “Even an average of several polls will have enough underlying uncertainty that you won’t be able to clearly distinguish who should be in and out.”

In Thursday’s Quinnipiac poll seven candidates are tied with each other—at zero percent—owing to the ±3.8 percentage point sampling error.

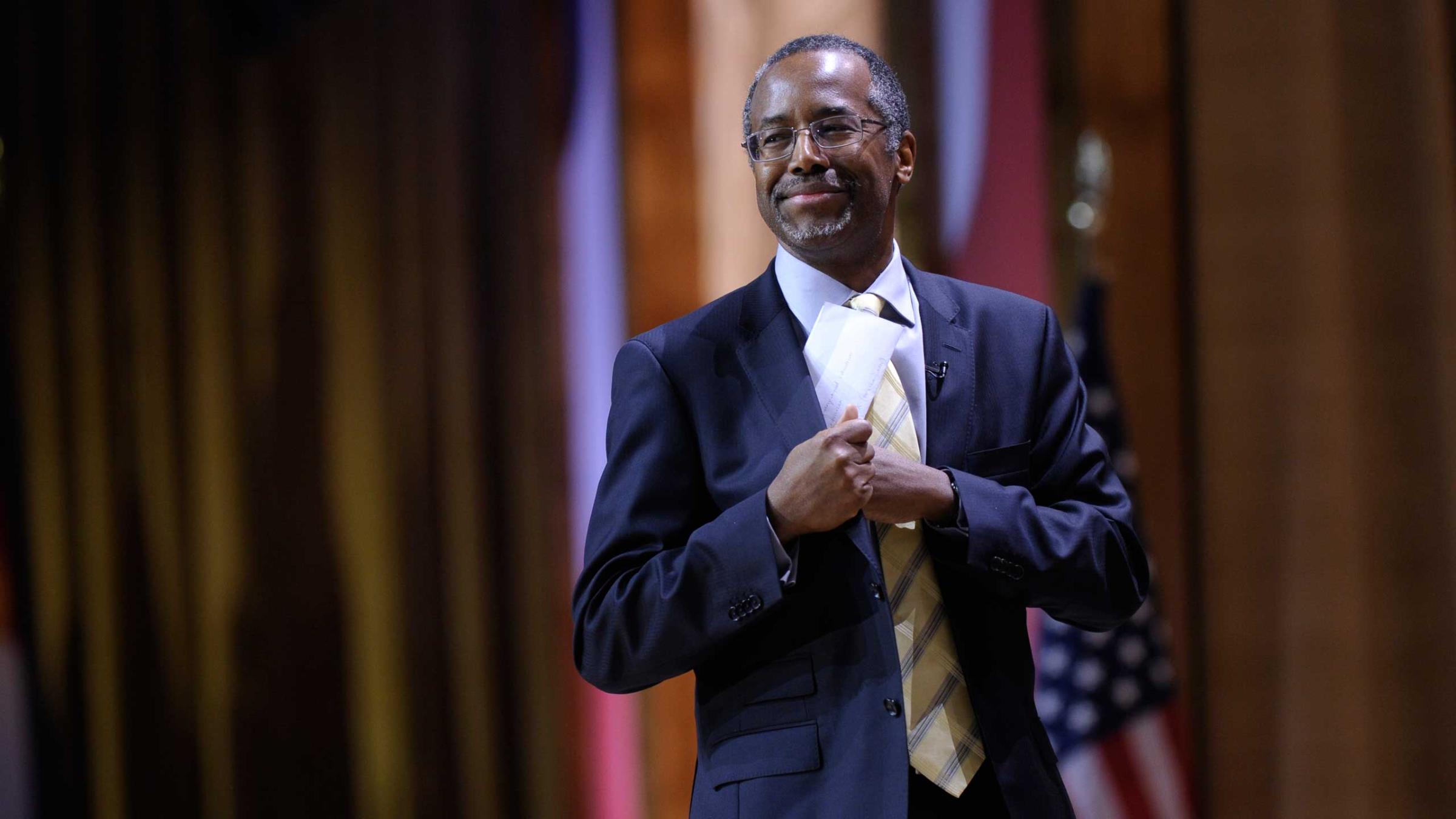

In a letter to members of the RNC Friday, Ben Carson, the retired neurosurgeon safely on the debate stage with poll numbers in the high single-digits, urged a change. “In the past this type of rule has been used to keep ‘fringe’ candidates off the stage,” he wrote. “None of these men and women deserves this exclusion.”

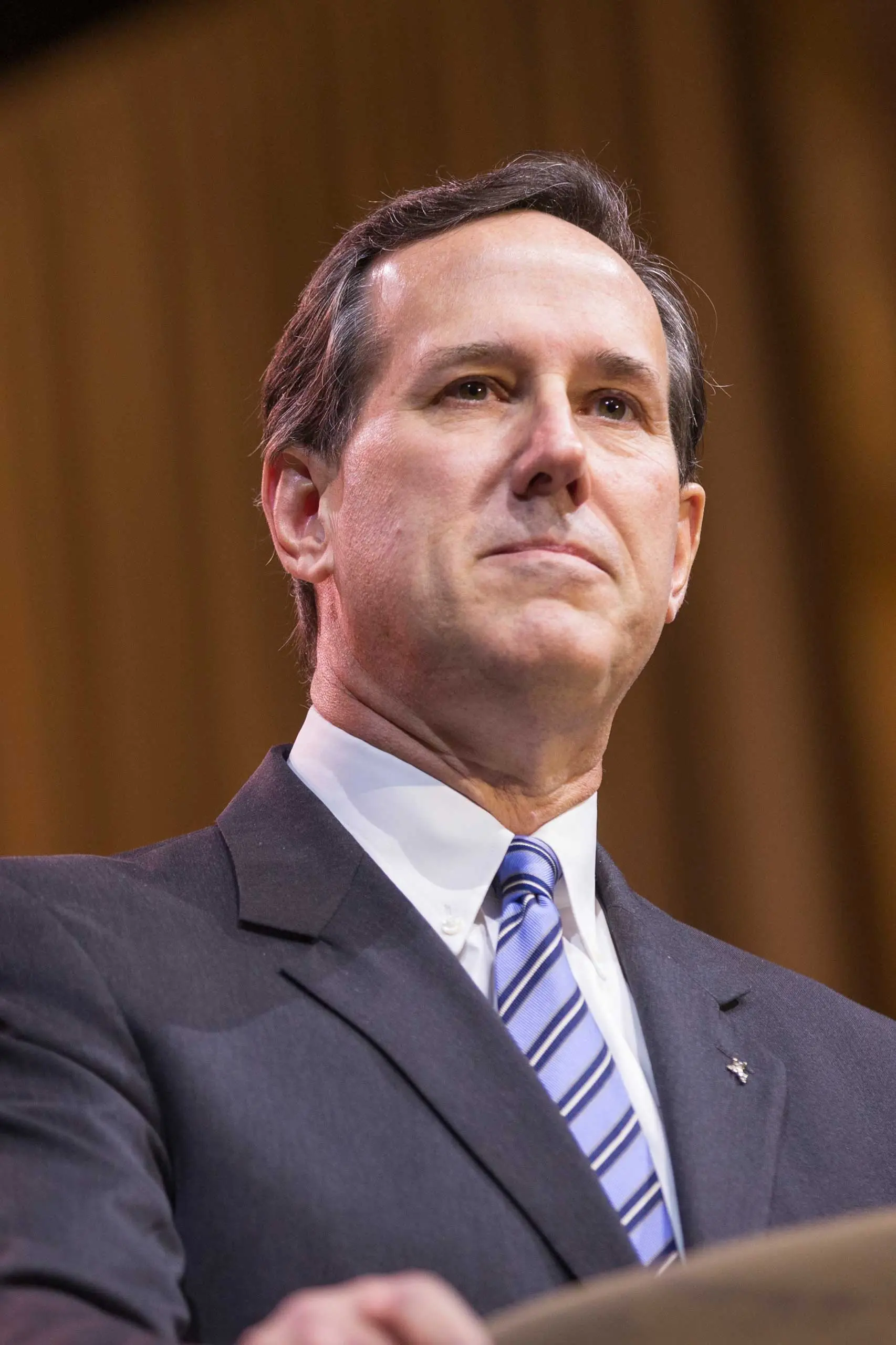

“I’m probably the best person to comment on this,” former Pennsylvania Sen. Rick Santorum told National Journal Friday. “In January of 2012 I was at 4 percent in the national polls, and I won the Iowa caucuses…And so the idea that a national poll has any relationship to the viability of a candidate—ask Rudy Giuliani that. Ask Phil Gramm that.”

It’s in Santorum’s interest to undermine the polling standards. The 2012 runner-up’s national numbers are dismal—he polled at zero percent in a Quinnipiac University survey released Thursday.

As a practical matter, polling in the U.S. has grown more difficult as American attention spans have dwindled and more people have moved to cell phones. The gold standard—live surveys, conducted by actual human questioners—has grown more difficult as people cut phone lines to their homes. Most reputable surveys now include cell phone lines in an effort to ensure those who have cut the cord are represented.

But polling in primaries is has always been difficult. Andrew Gelman, a professor of statistics and political science at Columbia University, wrote in 2011 of the difficulties endemic to polling in nominating fights. “The candidates in a primary election are of the same political party and typically differ in only minor ways in their political positions, so it is easier for voters to change their opinions,” he wrote. “Primary election campaigns can be highly unequal too, with different candidates pouring their efforts into different states. And during the heat of primary season, voters may have only a week or two to make up their minds in light of the news from the most recent primaries elsewhere.”

“Primary polls can fluctuate a great deal depending on which candidate is getting news coverage,” adds Sides. “And that news coverage may arise because of events that really aren’t that significant. For example, Herman Cain’s victory in the meaningless Florida straw poll catalyzed news coverage and his poll numbers. So there is the question of whether, at any particular point in time, good poll numbers are really indicative of a viable candidacy.”

And in a field with at least 15 candidates, it’s even tougher.

“You can’t poll 15 candidates and expect voters to keep paying attention,” scoffs one 2016 strategist, suggesting that poll accuracy will suffer because only those willing to sit through a long list of names won’t hang up.

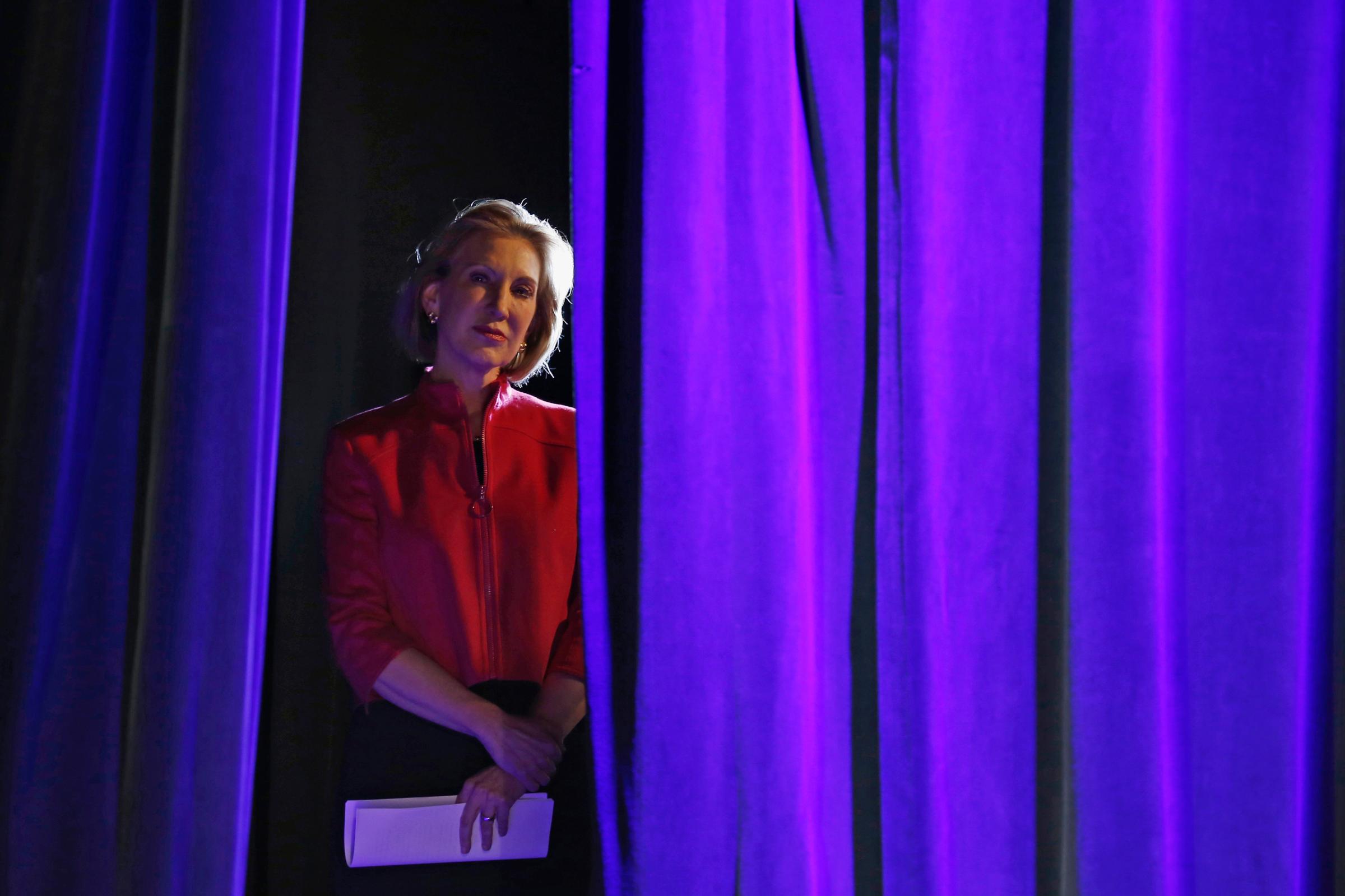

For much of the cycle so far, news outlets and pollsters have only polled subsets of candidates for just this reason, including just the top eight or 10 candidates at a given moment in their surveys. Many reputable surveys of the 2016 field have chosen to exclude potential 2016 contenders, like Donald Trump and Ohio Gov. John Kasich. Others have excluded longshots like Louisiana Gov. Bobby Jindal or former HP CEO Carly Fiorina. The Quinnipiac University poll released Thursday is one of the first national polls to include all 16 Republican candidates.

Douglas Schwartz, the director of the Quinnipiac University Poll, tells TIME that typically they try to keep the list of candidates to a manageable six or eight, but that with the field so large and with support so diffuse, that they had to ask about all of them. It’s not without complication.

“We haven’t encountered the first issue in terms of people hanging up,” he said. It’s just more of an issue that so many of these candidates are not well known and that it’s tough for people to keep all the names in their head.”

The problem is not limited to polling, Schwartz adds. “It’s tough when you’ve got eight candidates and you’re asking people to try to get to know all eight candidates, research the background and learn the biography of people who are all pretty similar because they’re in the same party,” he said. “Now double it. It’s hard for voters too.”

But even those who make the cut shouldn’t be cheering either when in reality activists in a handful of states will decide.

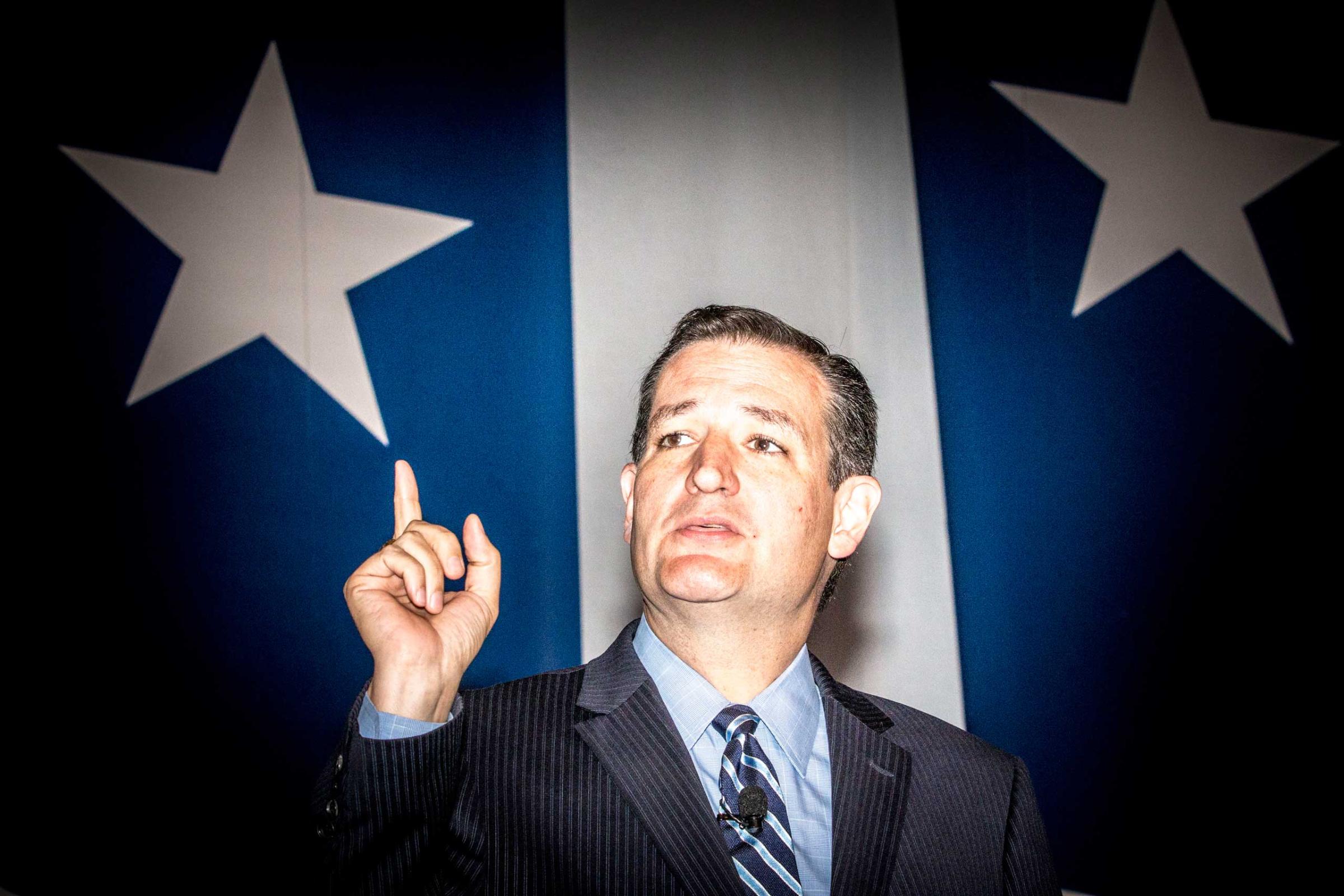

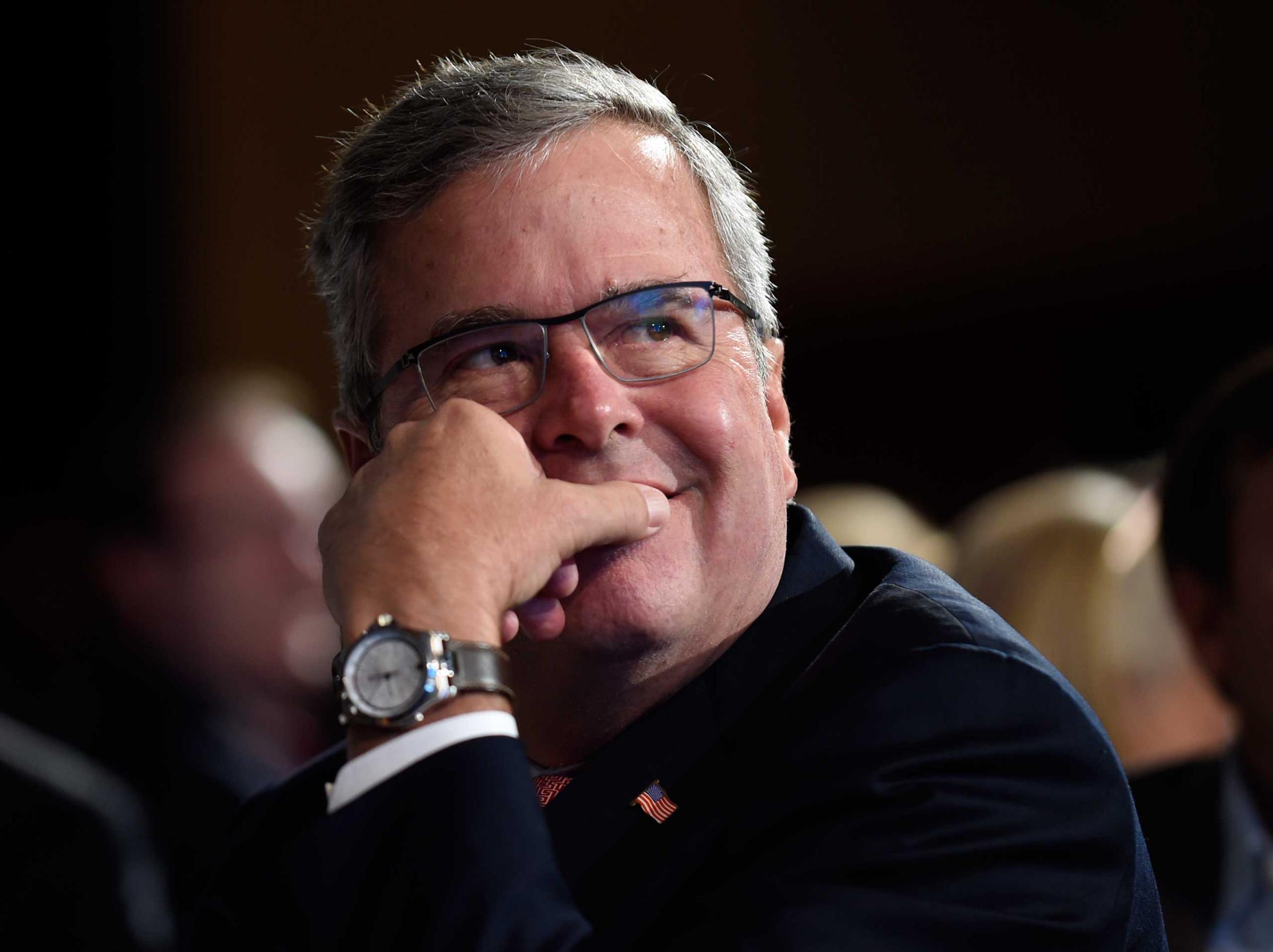

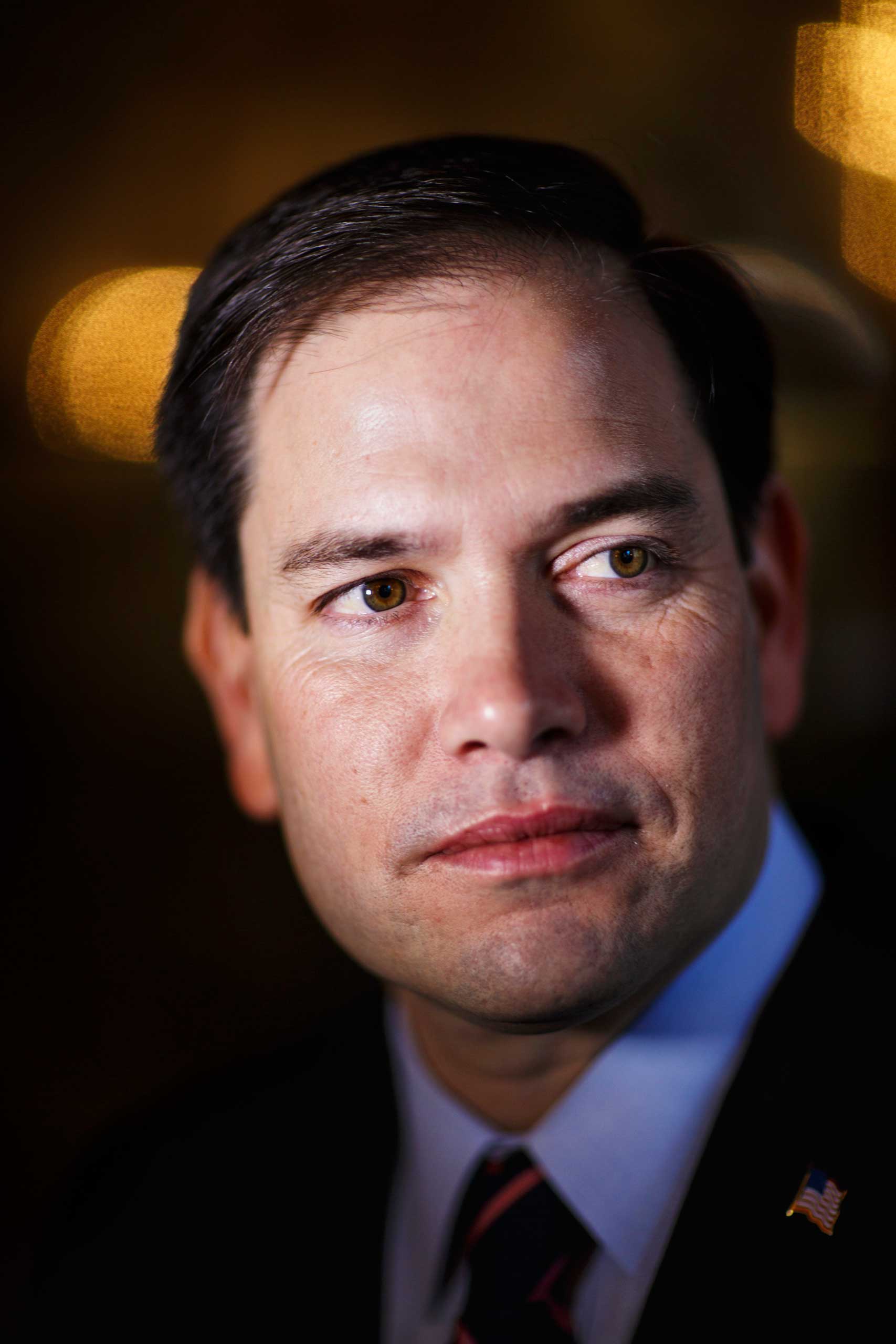

See the 2016 Candidates Looking Very Presidential

More Must-Reads from TIME

- How the Electoral College Actually Works

- Your Vote Is Safe

- Mel Robbins Will Make You Do It

- Why Vinegar Is So Good for You

- The Surprising Health Benefits of Pain

- You Don’t Have to Dread the End of Daylight Saving

- The 20 Best Halloween TV Episodes of All Time

- Meet TIME's Newest Class of Next Generation Leaders

Contact us at letters@time.com