The body lay along a fence line at the edge of a highway. He was a 23-year-old Salvadoran, according to the ID in his wallet, carrying a toothbrush and a picture of a young girl posing in a cap and gown. The man had spent days trudging through the sandy brush of South Texas, stripped to socks and underwear in the heat. When he collapsed and died, someone dragged the corpse toward the road, where it was spotted by a passing cowboy. By the time Brooks County chief sheriff’s deputy Benny Martinez arrived on May 21, the body was bleeding from the eyes.

Collecting the dead is one of the grim rituals of Martinez’s job. The young man from El Salvador was the 24th undocumented immigrant to perish in Brooks County this year. Over the past six years, more than 400 bodies have been discovered in the desolate rural jurisdiction, whose 7,200 people are spread across 943 sq. mi. (2,440 sq km) of cactus and mesquite. “You never get over it,” Martinez says.

The body count makes Brooks County one of the deadliest killing fields in the U.S. border crisis. But it is not actually on the border. The county is a graveyard for migrants because of the three-lane traffic checkpoint, operated by U.S. Customs and Border Protection, that sits on U.S. 281, 70 miles (115 km) north of Mexico. To circumvent the checkpoint, coyotes drop carloads of undocumented immigrants along the highway a few miles south, where they embark on an arduous hike through private ranchland with plans to rejoin their ride north of the station. For undocumented immigrants entering the U.S. in South Texas, the multiday trek is the most perilous leg of a journey that starts with a payment (often $5,000 to $10,000, according to authorities) to coyotes in their home countries, who stash their clients at squalid border safe houses and shepherd them across the Rio Grande aboard inflatable rafts.

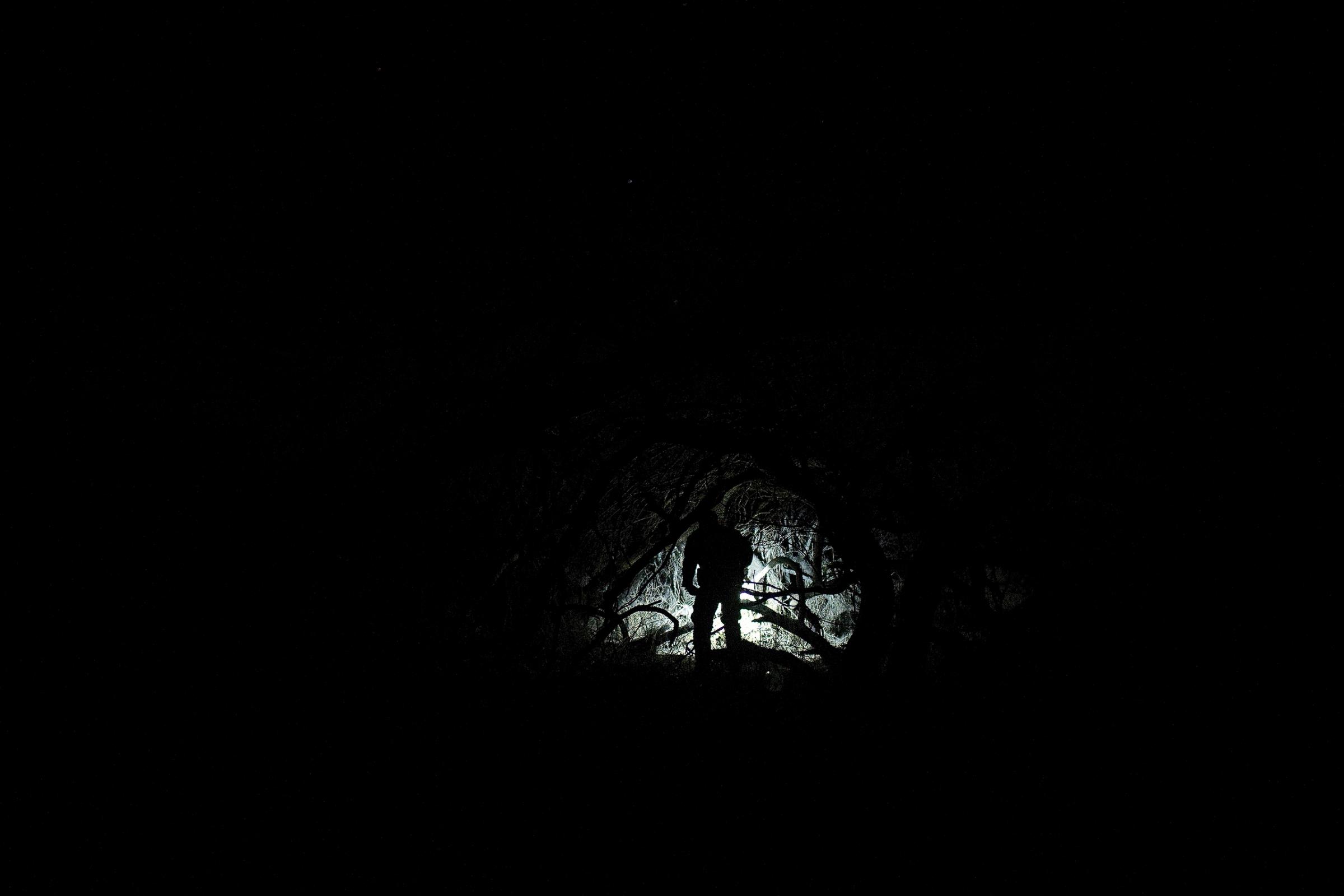

Since 2006, when she became a staff photographer at The Monitor in the border town of McAllen, Tex., Kirsten Luce has been documenting immigration issues on both sides of the U.S.-Mexico border. Now a freelance photographer, Luce made extended reporting trips to Brooks and Kenedy Counties in January and March. She embedded with the U.S. CBP, joining agents in the brush on both day and night patrols as they used footprints and censors to track the migrants during the difficult and dangerous walk around the Brooks County checkpoint.

“I hadn’t spent much time there in years, and it was a piece of the migration story that I wanted to revisit,” Luce says. “These are the places where most deaths occur. Migrants—often tired, thirsty and hungry after a couple nights in stash houses further south in Texas—succumb to heat exhaustion or dehydration while circumventing vehicle checkpoints on foot.”

“It wasn’t until I witnessed the conditions in these houses that I fully realized these migrants were beginning the hike in Brooks or Kenedy County with severely compromised health conditions,” Luce says. “The people who hold migrants in these houses coordinate with other smugglers to lead them around the checkpoints. All are directly or indirectly linked to the drug cartels operating with impunity in Northeast Mexico. In recent years, human smuggling (especially all the way from Central America) has become as profitable as drugs, and it’s harder to prosecute as smugglers often try to blend in with their group and get deported alongside them. The cartels now control all traffic across the Rio Grande and everyone must use a cartel-approved guide. If caught crossing alone, one could be beaten or disappeared.”

Despite all the attention to securing the border itself, often the best chance of intercepting the flow of people and contraband is at checkpoints on key roads leading north. “These interior checkpoints always intrigued me, because each migrant passing undocumented through the Rio Grande Valley essentially crosses two borders,” Luce says. In Brooks County, the enforcement checkpoint has pushed undocumented immigrants onto private ranches, where they are unprepared for the searing heat and arid terrain on what can be a 25-mile (40 km) detour around the patrol stations.

“Some arrange to get dropped off several miles south and spend a night or two hiking north, following a wide arc far from the road,” Luce says. “Others are more brazen, getting dropped off less than a mile from the checkpoint at one of several turn-around lanes off of Highway 281 or 77, the only two direct routes out of the Valley. Typically the migrants have no idea where they are or what they are facing ahead. One once asked me if we were in Houston, some 250 miles away.”

Photos: Documenting Immigration From Both Sides of the Border

Temperatures can reach triple digits in the summer. It’s easy to become disoriented and get lost. Migrants carry little food or water, and those who lag are left behind by their guides. “It’s the corridor of death,” says Eddie Canales, who runs the South Texas Human Rights Center, a few miles from the Falfurrias checkpoint in Brooks County. “There’s no telling how many remains are still out there.”

South Texas has struggled for years with the U.S. immigration crisis, but the problems deepened as migration patterns shifted. Beefed-up border security across former trouble spots in California, Arizona and West Texas prompted smugglers to find new routes through the Rio Grande Valley, while escalating violence in Central American nations spurred a wave of refugees searching for a path to the U.S. Illegal border crossings have dropped in 2015 with the end of the unaccompanied-minor crisis, and deaths in Brooks County are actually down from their peak of 129 in 2012.

But the impact still hits hard in places like Brooks County, which has just five sheriff’s deputies, and neighboring Kenedy County (pop. 400), where another border-patrol checkpoint sits astride U.S. 77. In these poor rural areas, recovering, identifying and burying the dead carries significant costs. Judge Imelda Barrera-Arevalo, the top elected official in Brooks County, estimates that dealing with the humanitarian crisis will consume 15% to 20% of the county’s budget this year. “It’s still our responsibility,” she adds, “whether we like it or not.”

To reduce fatalities, humanitarian groups and some ranchers have installed water stations. The border patrol has positioned rescue beacons on private land so migrants can buzz for help. Agents use ground sensors, cameras and blimps to surveil the sprawl. “I won’t be happy until the death toll is zero,” says Doyle Amidon, the patrol agent in charge of Falfurrias station. “But the nature of this area, and the fact that we are in the perfect location for illegal migrants to pass through here, it’s sort of the perfect storm.”

On one nighttime patrol, Luce joined border patrol agents as they tracked a group of 12 migrants for close to two hours. “There was something exciting about these pursuits. The air was cool and the moon was bright. We were fed and hydrated,” she says. “The migrants, however, had been traveling for days or weeks and were exhausted and dirty. They were as close as they’d ever been to relative freedom. They’d invested an untold fortune for this opportunity, an amount nearly impossible to pay back in their home countries. Their clothes were covered in leaves and stickers, any exposed skin covered in small scrapes from the brush.”

Eventually, they came upon the migrants hiding in a grove of mesquite. Agents surrounded the grove and moved in from all sides, working quickly to handcuff the migrants. Some tried to flee, but most remained perfectly still as they were detained.

“Any momentary thrill I had felt during the pursuit was replaced first by adrenaline and then by a hollow sadness,” Luce says. “The migrants’ resignation, and sometimes fear, is sobering for everyone. The air felt thicker as we hiked out, nearly a mile to the closest road. Everyone had a heavy heart, no one is rejoicing. I think many agents feel that they are rescuing these people from an uncertain fate, which is certainly true. They are doing their part to enforce the nation’s immigration laws, albeit some 80 miles north of the border, on privately owned land.”

Kirsten Luce is a freelance photojournalist based in New York.

Alex Altman is TIME’s Washington Correspondent.

More Must-Reads from TIME

- Cybersecurity Experts Are Sounding the Alarm on DOGE

- Meet the 2025 Women of the Year

- The Harsh Truth About Disability Inclusion

- Why Do More Young Adults Have Cancer?

- Colman Domingo Leads With Radical Love

- How to Get Better at Doing Things Alone

- Michelle Zauner Stares Down the Darkness

Write to Alex Altman at alex_altman@timemagazine.com