When generals start playing with syntax, hold on to your wallets. “The ISF (Iraqi Security Forces) was not driven out of Ramadi,” Army General Martin Dempsey, chairman of the Joint Chiefs of Staff, said Wednesday. “They drove out of Ramadi.”

That grammatical shift from the passive to the active voice—Dempsey boasts a master’s degree in literature from Duke, after all—highlights just how badly Iraq’s U.S.-backed war against the Islamic State in Iraq and Syria is now going.

“We saw this movie—it was called Vietnam,” says Anthony Zinni, a retired four-star Marine general who began his career in that country in 1967, advising South Vietnamese marines. “They are losing credibility. We went through this in Vietnam where we touted pacification and winning all these battles while strategically losing the war.”

The growing disconnect between what’s happening on the ground, and what U.S. military leaders say is happening on the ground, has consequences. “For the last 13 years, even though we have not done well in either Iraq or Afghanistan, the American people have stayed with the military,” Bing West, a one-time Marine infantryman and former assistant defense secretary, says. “But if the American people now see a gap between the reality and what the military is telling them, then you end up with the corrosiveness that we saw in Vietnam.”

Dempsey’s verbal twist—implying that ISIS didn’t force some of Iraq’s best troops out of the city, but, thanks in part to American training, they left in a crafty and bold military move—comes on the heels of a Friday briefing at the Pentagon that Saturday revealed to be close to fiction.

“We firmly believe [ISIS] is on the defensive throughout Iraq and Syria,” Marine Brigadier General Thomas Weidley told Pentagon reporters in a teleconference from the region. “The Iraqis, with coalition support, are making sound progress,” Weidley, chief of staff of Operation Inherent Resolve, the anti-ISIS operation, added. “The coalition will continue to support the government of Iraq as they conduct operations in Ramadi.”

The next day, after a series of bombings, ISIS fighters took over Ramadi after Iraqi troops fled, collecting a half-dozen U.S.-provided tanks and 100 vehicles abandoned by the Iraqis in their rush to drive out of the capital of Anbar province. ISIS forces killed an estimated 500 Iraqi troops and civilians, while 25,000 residents fled the city. In addition to Ramadi, they now occupy the major Iraqi cities of Mosul and Fallujah.

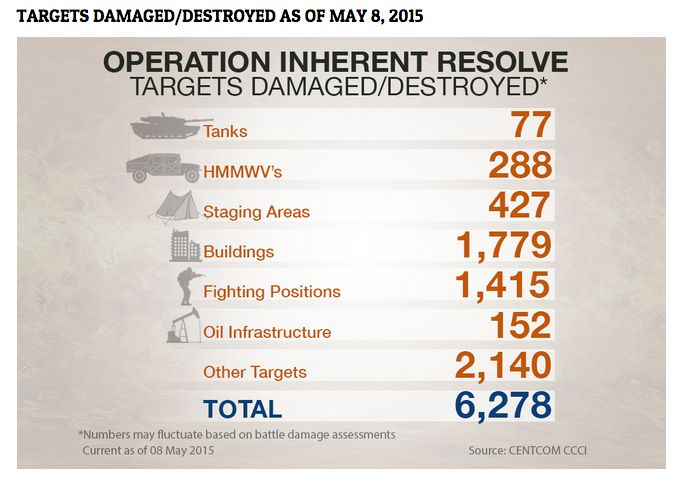

Pentagon officials argue that the long-term U.S. strategy—stepped-up (re)training of Iraqi troops, backed by U.S. and allied air power—ultimately will prevail. They note that they have said from the start that the anti-ISIS campaign could take three years. The U.S. joined the fight last August, and has been flying nearly-daily air strikes against ISIS targets in Iraq and Syria. There’s a push “for a narrative about success, and that the strategy is fine, that influences different echelons of our government and military to not go outside that narrative,” says Derek Harvey, a one-time Army intelligence officer now at the University of South Florida. “That disconnect risks undermining their credibility.” The retired colonel, who worked for Army general David Petraeus, believes the U.S. focus on vehicles destroyed “measures progress by elements that are irrelevant and meaningless.” The U.S.-led effort is additionally handicapped because it has been done half-heartedly. “A bad strategy that is not properly resourced has a zero chance of success,” he says.

The Pentagon has deployed about 3,000 U.S. troops to train Iraqi forces, although President Obama has restricted their efforts to areas well behind the front lines. That means they can’t call in air strikes and gather front-line intelligence that could give Iraqi forces a critical advantage. Zinni contends a relatively small U.S. combat force on the ground inside Iraq could destroy ISIS, but Obama’s aversion to casualties has ruled that out. “Everybody with any kind of military experience in the Pentagon knows damn right well that this strategy isn’t going to work because you’re counting on breaking his will and there’s no sign of that happening,” he adds. “This strategy has got to bring up Vietnam, where they were saying, `Give us time, we’ll kill enough of them and hit a tipping point.’ The problem is they have not found the tipping point.”

The American people, following more than a decade of war, may not be in the mood for another two years of fighting with an unreliable ally. The Pentagon is doing what it can despite the restrictions the White House has imposed. But the over-selling of military progress in battling ISIS is the first step in a treacherous march toward disillusionment that the U.S. military has now begun.

“If the battle is going against you—and it is—do not put yourself in the position where the credibility of the U.S. military is undermined,” West says of Dempsey’s drive-time comment. “If it doesn’t look good, say nothing.”

More Must-Reads from TIME

- Cybersecurity Experts Are Sounding the Alarm on DOGE

- Meet the 2025 Women of the Year

- The Harsh Truth About Disability Inclusion

- Why Do More Young Adults Have Cancer?

- Colman Domingo Leads With Radical Love

- How to Get Better at Doing Things Alone

- Michelle Zauner Stares Down the Darkness

Contact us at letters@time.com