Spoilers for the season finale of Mad Men below:

“There’s more to life than work.” –Stan Rizzo

Is there? The entire finale of Mad Men seemed to be making that point, or at least, it found the series’ central characters wrestling with the issue. Peggy Olson found love at work–no mortal can resist Stan’s suede and turquoise for long–while also finding a calling there. Joan found that her work cost her a relationship, as Richard’s supportive talk turned out to be all talk–yet when we last saw her, she seemed to have managed to integrate her work with her life. Even Roger Sterling ends his story out of the office, ordering champagne happily with Marie.

And then of course there was Don, whose hobo journey led him at the end away from the office, by way of the Bonneville Salt Flats, to a meditation center in California, where, stripped of everything–job, home, car, power suits, connection with family and friends and even hippie pseudo-niece Stephanie–he gives in to the vibe, breaks down in encounter group and shows up to meditate and greet Mother Sun. He closes his eyes. He gives himself over. He chants, “Om.” He smiles. His skin relaxes, his nostrils flare. He seems at peace. And we hear a bell, a chime of clarity.

Or is it just an idea lightbulb? A moment later, we hear the lines of “I’d Like to Teach the World to Sing,” the famous Coca-Cola world-peace-through-carbonation anthem from 1971. (Kudos, by the way to Vox and Uproxx for nailing the final-song prediction.)

[Incidentally, it’s true that the finale did not make explicit, in so many words, that Don wrote the Coke ad; it’s possible, I suppose, that it could have been Peggy, though then I’m not sure its connection to Don’s ending meditation. In that way, the ending was more Sopranos-like–open to endless interpretation–than I would have expected. But that’s my operating theory for now. I am glad to hear arguments to the contrary!]

So last things first: that ending. As a tag on Don’s story it was both incredibly clever and emotionally underwhelming–the opposite, really, of what I might have expected from Mad Men‘s finale. It does a brilliant, instantaneous double-twist, suggesting in one moment that Don has finally, through being stripped down, reached a moment of spiritual growth–and then that, really, he’s simply seen it as all b.s. and come up with one more way to sell product. He has looked into the eye of eternity and seen a Clio.

Ingenious? Yes. But it’s also, at first blush, much more bleak and cynical about Don’s ability to change and grow–much more Sopranos-like, in other words–than you would expect from a series that gave us the moving end moments of “In Care of” at the end of season 6. If that’s what happened in that instant, Mad Men has given TV its most cheerful, upbeat, miserable ending in the history of finales.

Because think about what it’s saying. Don has lost pretty much every human connection. He’s essentially accepted that the best thing for his children is to surrender their care to another man after the death of their mother. He’s unable to accept the love or encouragement of his protegé Peggy over the phone. He’s become the lonely, cold bottle on the refrigerator shelf in poor Leonard’s dream. And that has, apparently, made him a better ad man than ever: made him able, in fact, to come up with one of the most iconic ad campaigns of the 1970s (which, symmetrical with the pilot, is I believe the show’s first use of a real advertising campaign/slogan since Lucky Strike’s “It’s Toasted”).

Intellectually, I can accept that as both an example of how advertising co-opts ideals and as a statement of Don accepting that he is who he is–Don Draper, ad man, not Dick Whitman, spirit-questing, California-dreaming wanderer. It’s a satisfying idea to wrestle with. But this isn’t all about ideas. It’s about, as Don said to Peggy in season 2: “You, feeling something.” And where I’m sitting, early morning after the end of Mad Men, I wanted its last minutes to make me feel more.

Part of the issue here, I think, was the structure of the episode–finales always being a tough thing, especially in a show like Mad Men that’s not driven by a singular plot goal. Don spent the entire episode separated from the rest of the central characters, except by phone. And the problem is, we care about him mainly in relation to them. When Don realizes that this is it for Betty, his face crumples, and he says, “Birdie”: devastating. Don in the company of a bunch of hippies somewhere in the vicinity of Big Sur? Not so much. (Some of Mad Men‘s weaker segments historically have been around the counterculture–that’s where its seams start to show–and this was no exception.)

“Person to Person,” meanwhile, was very busy back at home on the East Coast, too busy, as it tried to give many characters final moments with each other. (And yes: if it hadn’t, fans would have complained about that. Again, finales are hard!) At times, it seemed to sacrifice consistency for fan service. It felt great to see Joan offer Peggy a partnership in her production company–offering her the chance to “burn the place down” together–but it felt sudden considering how strained their relationship often was. Peggy and Stan’s hookup was a wish fulfilled–and the show had been pointing at it forever–but the sudden, blurting I-love-you over the phone felt very convenient and not very Mad Men.

On the other hand, if you’ve seen Sally Draper as the secret protagonist of Mad Men, “Person to Person” delivered. Kiernan Shipka was absolutely riveting as Sally essentially took the parental role in her family, giving her father the mature argument that he needed to step back and let his sons have continuity with Henry, then coming home to have the honest talk with Bobby that Betty couldn’t. This was a dramatic personal change, but in a way that felt earned and convincing. Don told Sally earlier this season that she was indeed like her mother and father; but who would have guessed, after that childhood, that she might mature into a better version of both?

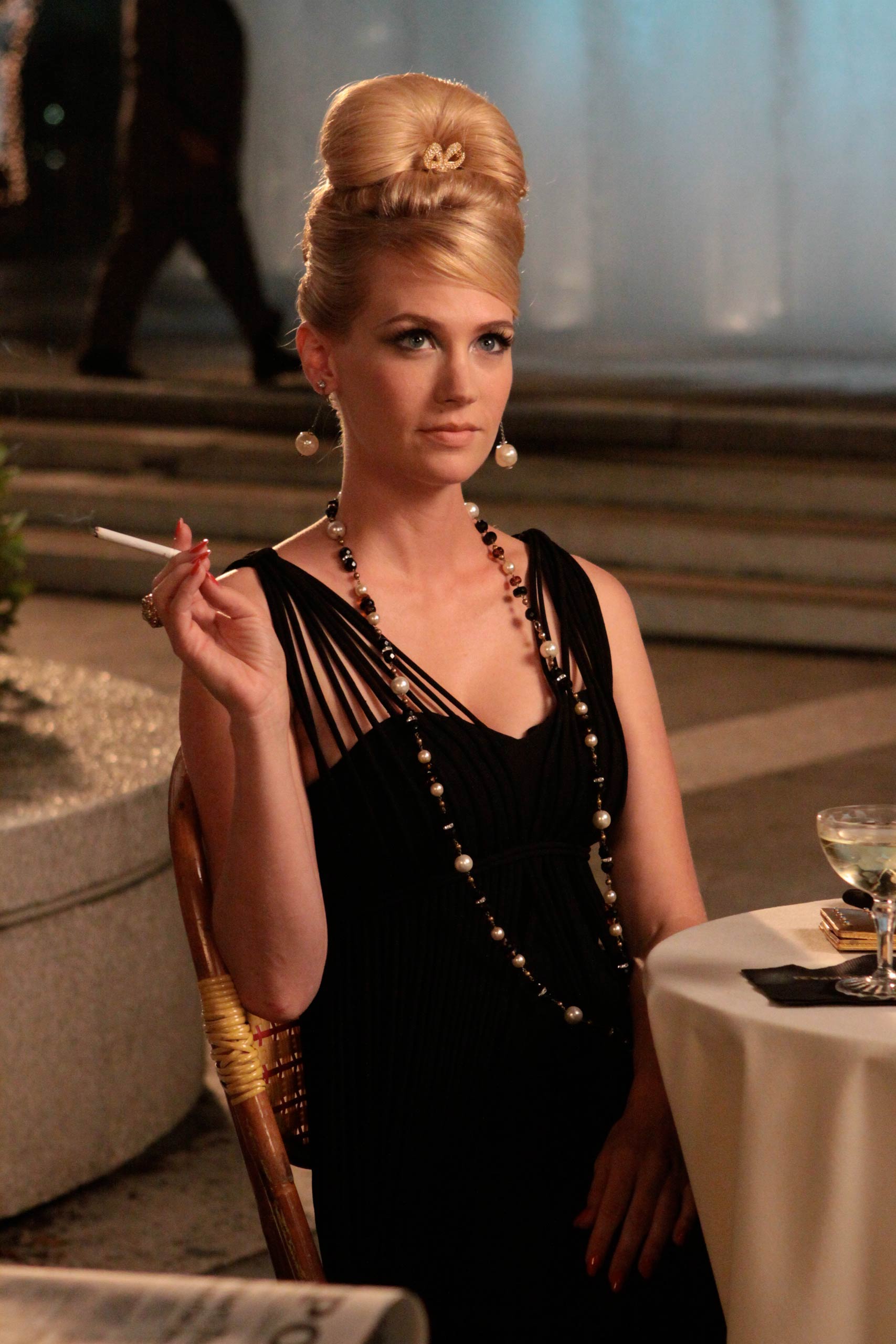

The 10 Best Outfits From Mad Men

Sally’s storyline was probably the most conventionally satisfying of the finale’s shambling first hour (and let’s not forget January Jones, who got to go a long way to redeem a sometimes-misused character in these final episodes). As a conventional finale, Mad Men’s was not one of TV’s best, and there have been far better hours of the series over its run.

And yet right now, around 1 in the morning, it’s the weird, not-conventionally-satisfying last ten minutes of the episode that I’m still wrestling with. And that’s testament to Mad Men‘s determination to be weird, to challenge, to irritate and prod and engage.

I mean, look again at the last ten minutes or so. Don, the protagonist of the series, says almost nothing in his final act. He exchanges a few depressed words–“I can’t move”–with a group leader whose name we don’t know and we don’t care to. He goes to a seminar with her, has an opening to speak, and… doesn’t. The man of words, the guy whom we could always count on to deliver a tour de force, epiphanic pitch speech, instead sits back and lets the show’s final story–Don’s story, for all intents and purposes–be told through some guy named Leonard.

And it’s devastating. Because it’s not a pitch. It’s the realization of an actual feeling human who feels that his life has come to nothing, that he doesn’t have love, or worse, that he has it and is simply incapable of accepting or recognizing it.

And Don? Don has no clever speech. After having turned the full force of this character on us for seven season through the power of language. Jon Hamm is left to give us his final moments through action only. His eyes watering as he absorbs his own situation through Leonard’s. Through a desperate hug, sobbing. And finally, by turning to us, full faced–not giving us the back of his head as in the show’s credits–and letting his face, finally, relax.

No words. No story. Only: “Om.” Don’s story ends with a Coke and a smile.

Is this TV’s saddest happy ending ever or it’s happiest sad ending ever? Has Don changed, or has he come 3000 miles to find what he’s always found in a conference room? Has the man who said love was invented by guys like him to sell nylons found a way to accept love and managed to channel it into his work? Or has he, devoid of love and connection and family, become a kind of advertising bodhisattva, slipping the bonds of earthly relationships the better to tap America’s Coke-buying chakras?

This is where I’m supposed to bluff my way through Don Draper-style and tell you I know. I don’t. And maybe after seven seasons we should be left with a better sense of whether Don’s final change is genuine or not. But the way Mad Men left me wrestling with those last moments–and may leave me wrestling with them for days or weeks–is testament to what a challenging, inventive show this series has been.

In the first episode of Mad Men, Don posed a question: “Do you know what happiness is?” Then he listed a bunch of comforts–the smell of a new car and so on–that had little to do with happiness but rather with the appearance of happiness as sold through advertising. This was happiness to him: an agreed-on construct that he was paid to invent.

Don Draper went through Mad Men‘s run as a man of mystery. He left us with one more, sponsored by Coke: Has he, after years of selling fake happiness, found The Real Thing?

Now for a last hail of bullets:

* So much turquoise in this episode. So. Much. Turquoise.

* The series ended, evidently, in November 1970, which didn’t give us the chance for many 1970s cultural moments. But there was at least a guest appearance from our old pal cocaine!

* You might have recognized the naked encounter-group guy as Brett Gelman, who played a therapy-group member in Matthew Perry’s short-lived Go On. Who’d have thought that, after all these years, Mad Men would end with a tribute to Go On?

* One of the best exit lines of the episode went to, of all people, Meredith: “I hope he’s in a better place.” “He’s not dead.” “There are a lot of better places than here.”

* Seriously, whoever had “Stephanie is a major character in the finale” on your office pool, you are doing all my Emmy ballots from now on.

* Whatever issues I had with the sudden romcom resolution to Stan and Peggy’s love story, Elisabeth Moss’ read of her reaction–“What?”–was priceless.

* In the interest of kicking off discussion and not pulling an all-nighter–unlike Joan, I have nothing to sniff off my fingernail–I decided to err on the side of finishing this review sooner. Which means I probably erred on some other sides too, and I certainly didn’t cover every last scene in the episode. I may write more later, and I apologize in advance for any omissions, errors or brain farts. (As Ginsberg once said, my couch is full of them.)

* On a personal note: this one goes out to Richard Corliss, the late TIME film critic and occasional Mad Men recapper, who I wish I could talk over tonight’s finale with.

* Above all, it’s been a pleasure getting to dig into this richly rewarding show for the past eight years, and to have a community of sharp-eyed readers to do it with. I reviewed (nearly) every episode of this series for the first four seasons, and wrote about the show recurringly over the final three. Few series reward the kind of analysis (or overanalysis) that this has–and few shows have attracted the kind of close-reading fanbase that I’ve found in the comments here and on social media. For me, a great part of the experience of watching and dissecting Mad Men has been what you’ve brought to it. Thanks for riding in the time machine with me.

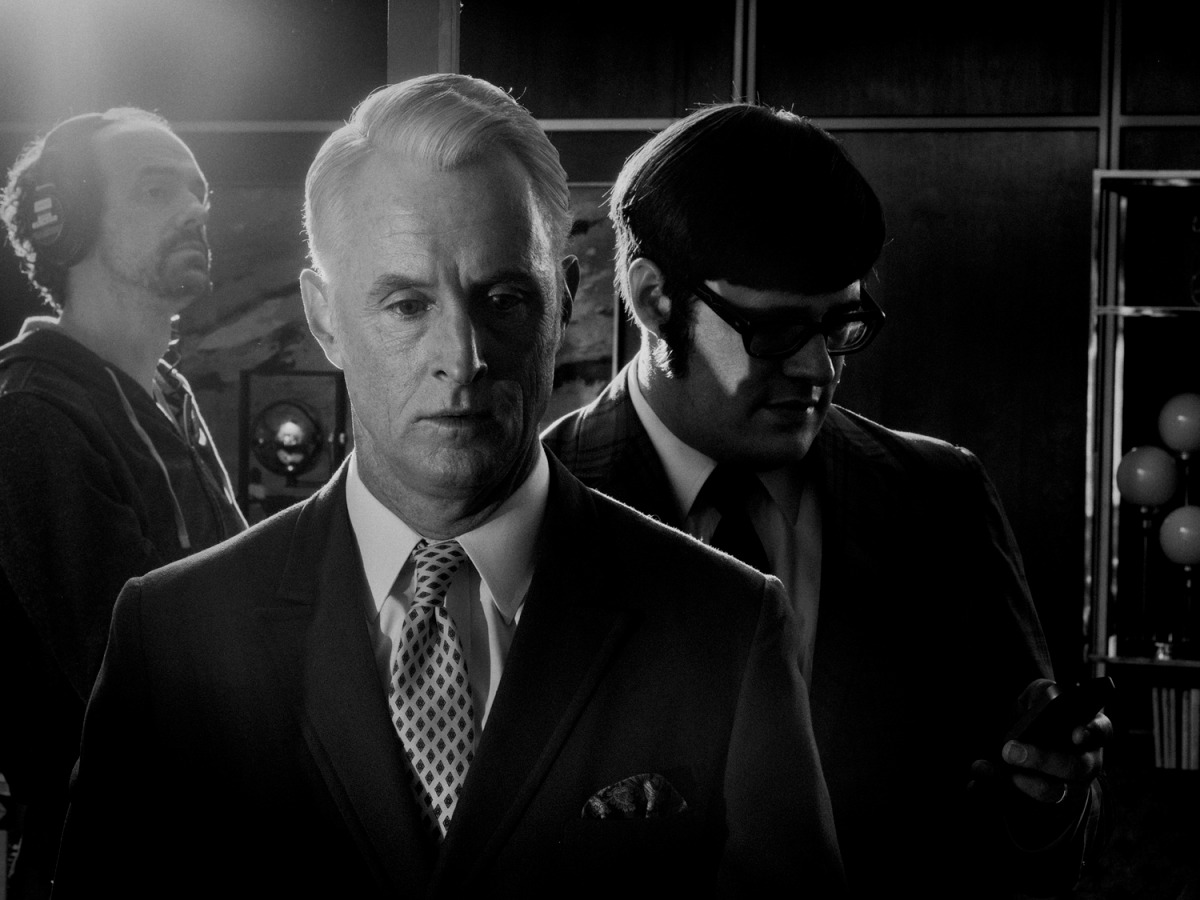

'Mad Men' Up Close: Photos From the Set of the Celebrated Show

More Must-Reads from TIME

- Cybersecurity Experts Are Sounding the Alarm on DOGE

- Meet the 2025 Women of the Year

- The Harsh Truth About Disability Inclusion

- Why Do More Young Adults Have Cancer?

- Colman Domingo Leads With Radical Love

- How to Get Better at Doing Things Alone

- Michelle Zauner Stares Down the Darkness

Contact us at letters@time.com