In 1963, the political theorist Hannah Arendt added a chilling (and, ultimately, controversial because so often misunderstood) phrase to the international lexicon: “the banality of evil.” Arendt coined the provocative expression in her book, Eichmann in Jerusalem, which in turn grew out of her reporting for the New Yorker on the trial of one of the principal Nazi officials behind the Holocaust, Adolf Eichmann.

In Arendt’s view, Eichmann was an at-once monstrous and pathetic creature who represented the apotheosis of the Third Reich’s unique obsession with mass slaughter on one hand, and rote, business-like documentation and organization on the other. Here was a man, after all, who entirely relied at trial on the now-infamous defense that he had merely “been following orders” when he organized the transport of Jews and other “undesirables” to Nazi death camps.

For Arendt, such reasoning was not evidence of pure, unmitigated evil, but instead showed that subsuming one’s humanity and decency in a system as murderous as the Third Reich’s was nothing more (or less) than an abandonment of morality in the face of something bigger. (Not, Arendt insisted, in the face of something better, or something more worthy of admiration — but something bigger. Eichmann, after all, admitted that his ruthless efficiency in carrying out the “final solution” derived as much from a desire to further his career as from any profound ideological sympathy with the Reich’s stated aims of genocide-driven empire.)

Critics of Arendt’s “banality of evil” formulation, meanwhile, argue that her theory — argued to its extreme — could actually absolve war criminals of any crimes at all. “If someone like Eichmann is, in the end, just like everyone else,” the reasoning goes, “and we’re all potential Nazis, then how can we judge his innocence or his guilt?” The only problem with that proposition is that Arendt, in Eichmann in Jerusalem, preemptively scuttles it by pointing out that, while we might all be capable of Nazi-like savagery, the entire point of free will and living a moral life is that we choose whether or not to act savagely.

The potential for criminality is not the same as acting in a criminal way. Arendt’s critics often ignore or willfully blur that distinction.

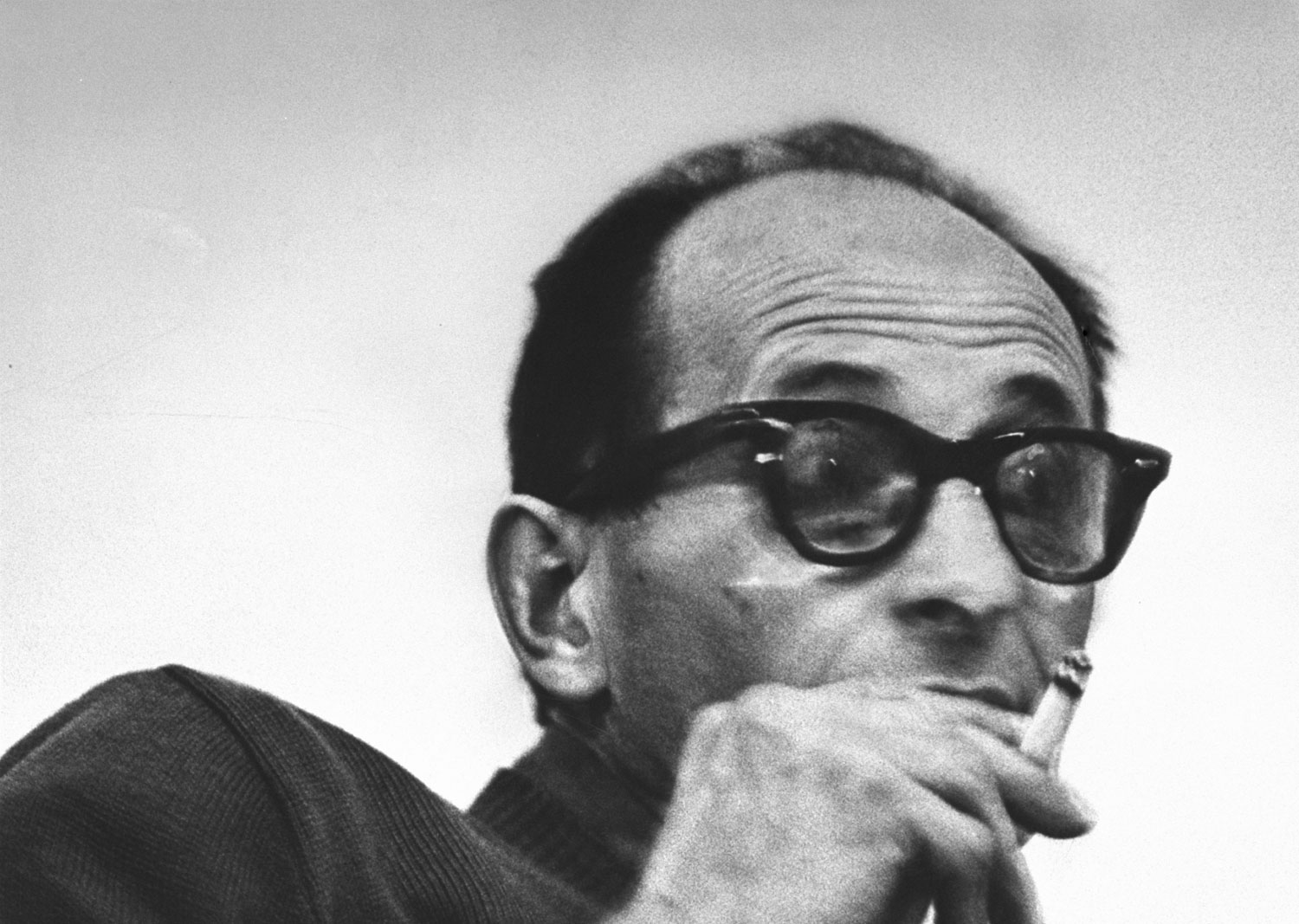

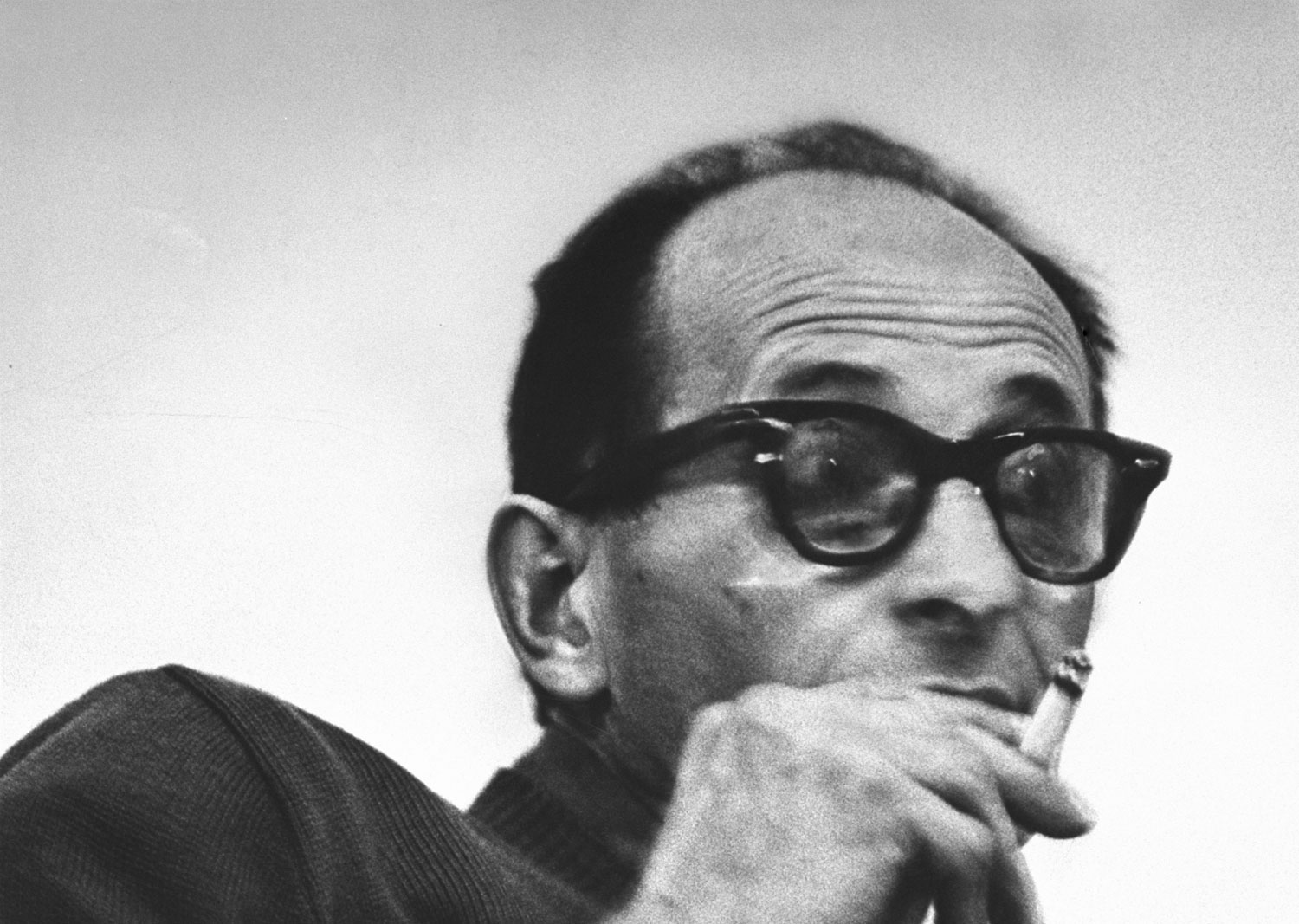

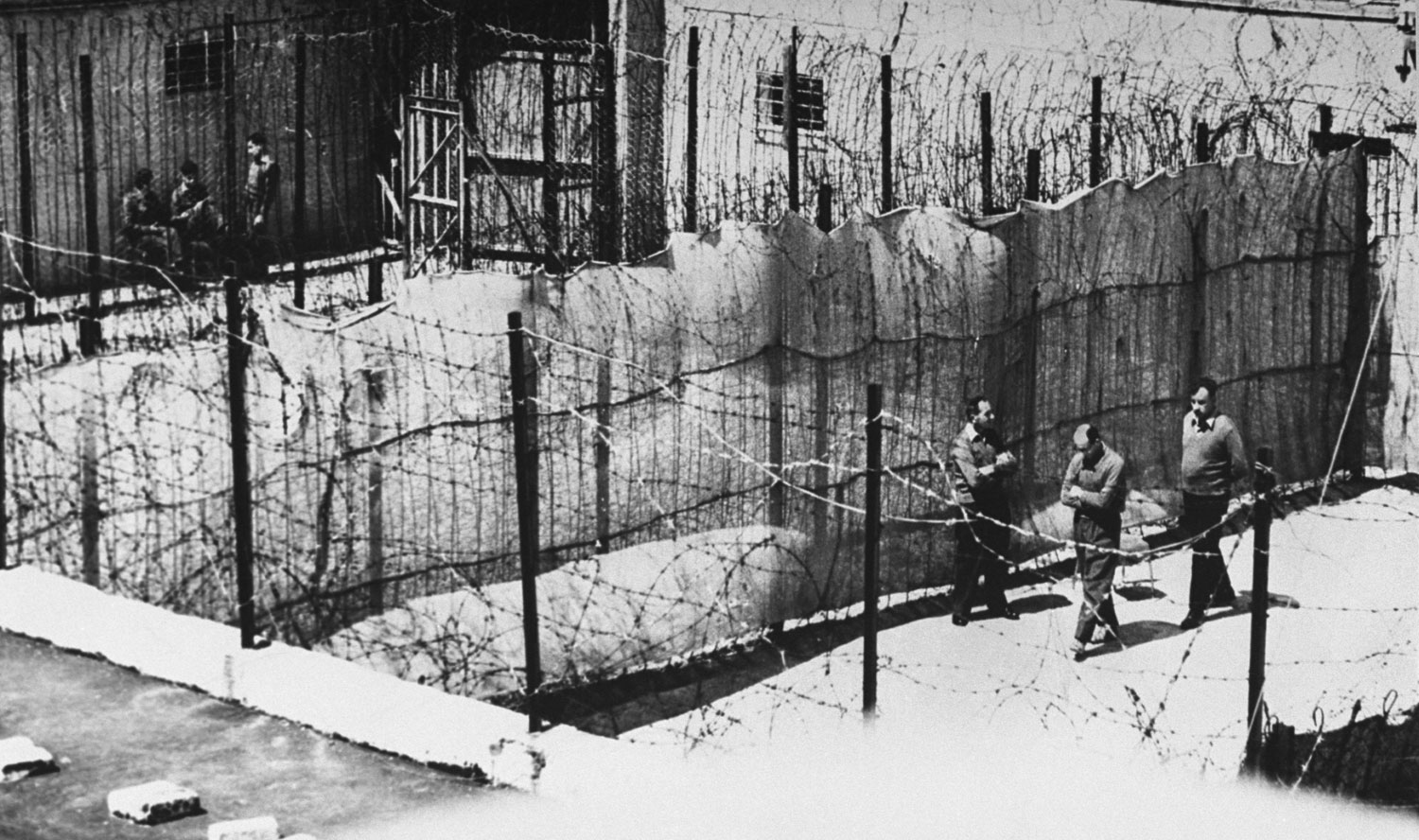

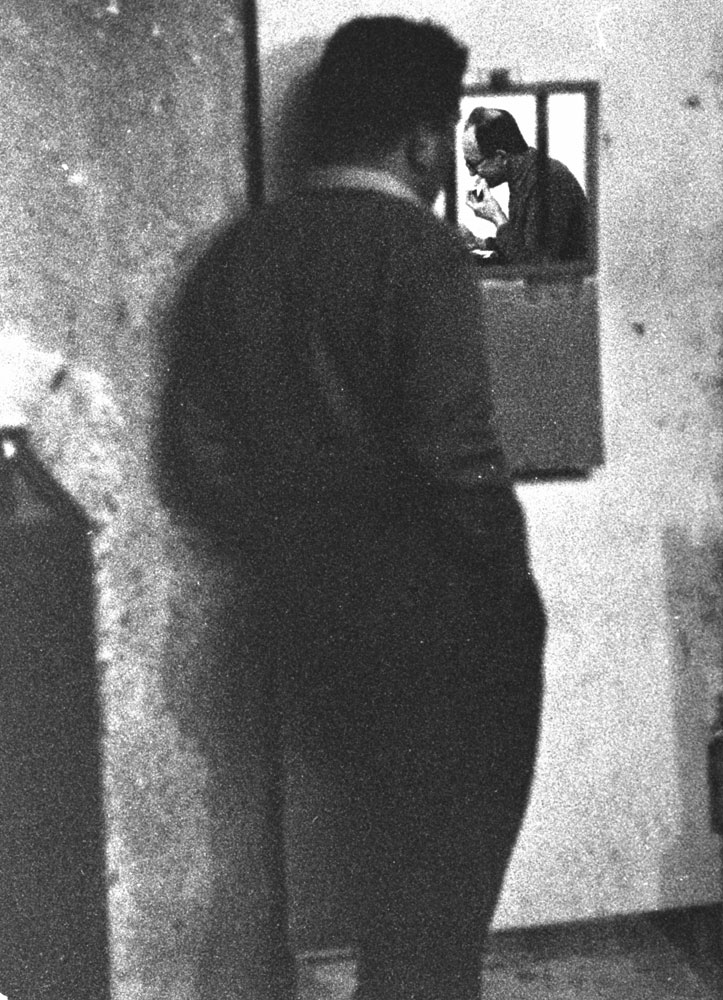

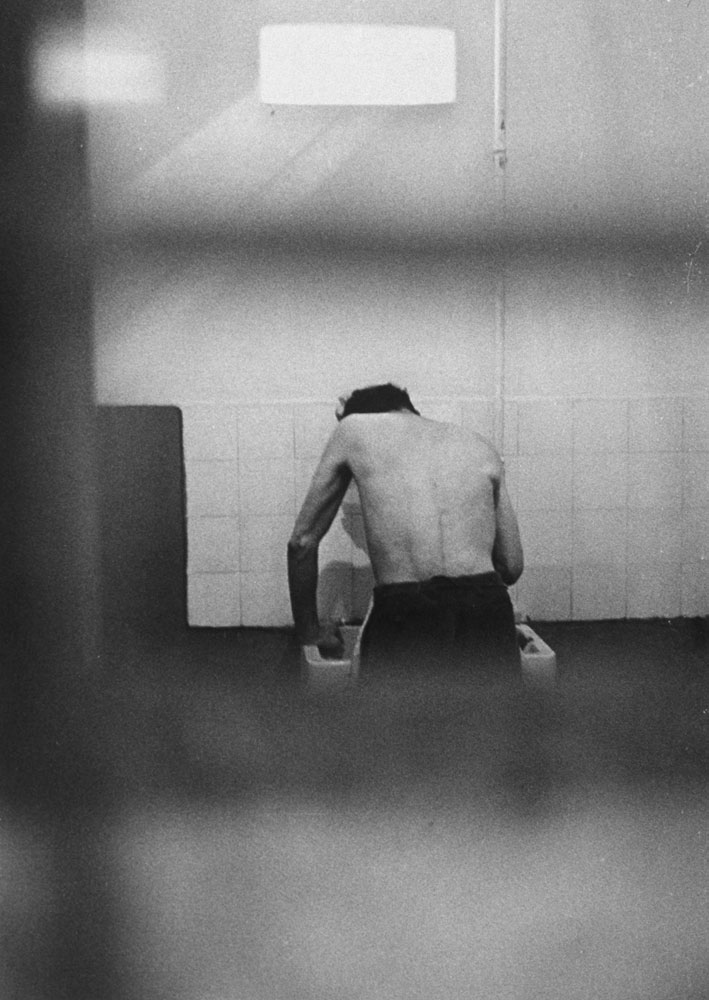

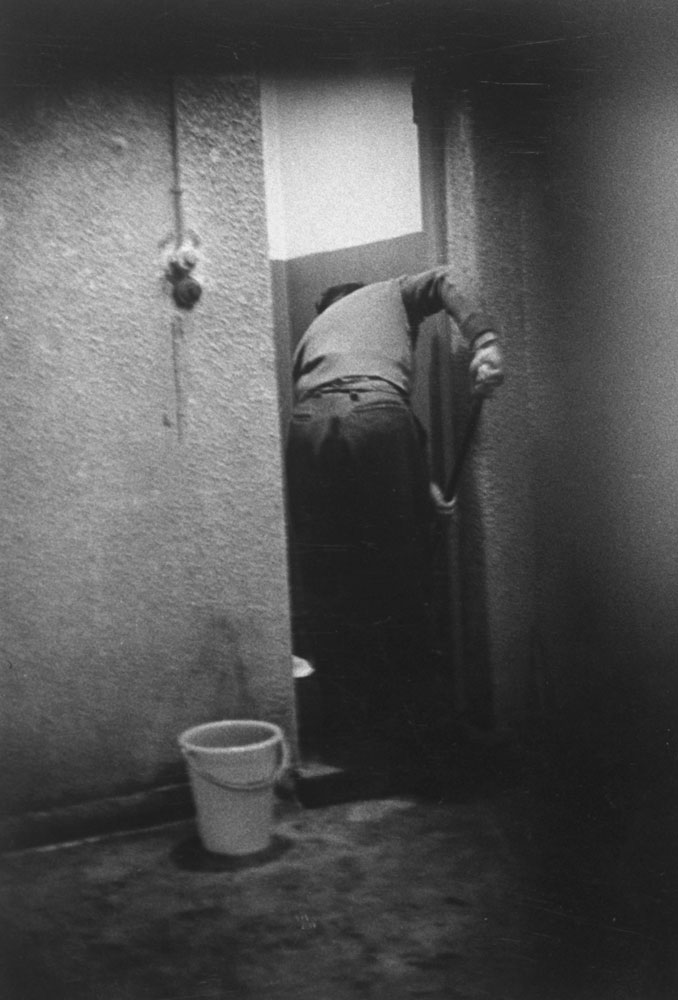

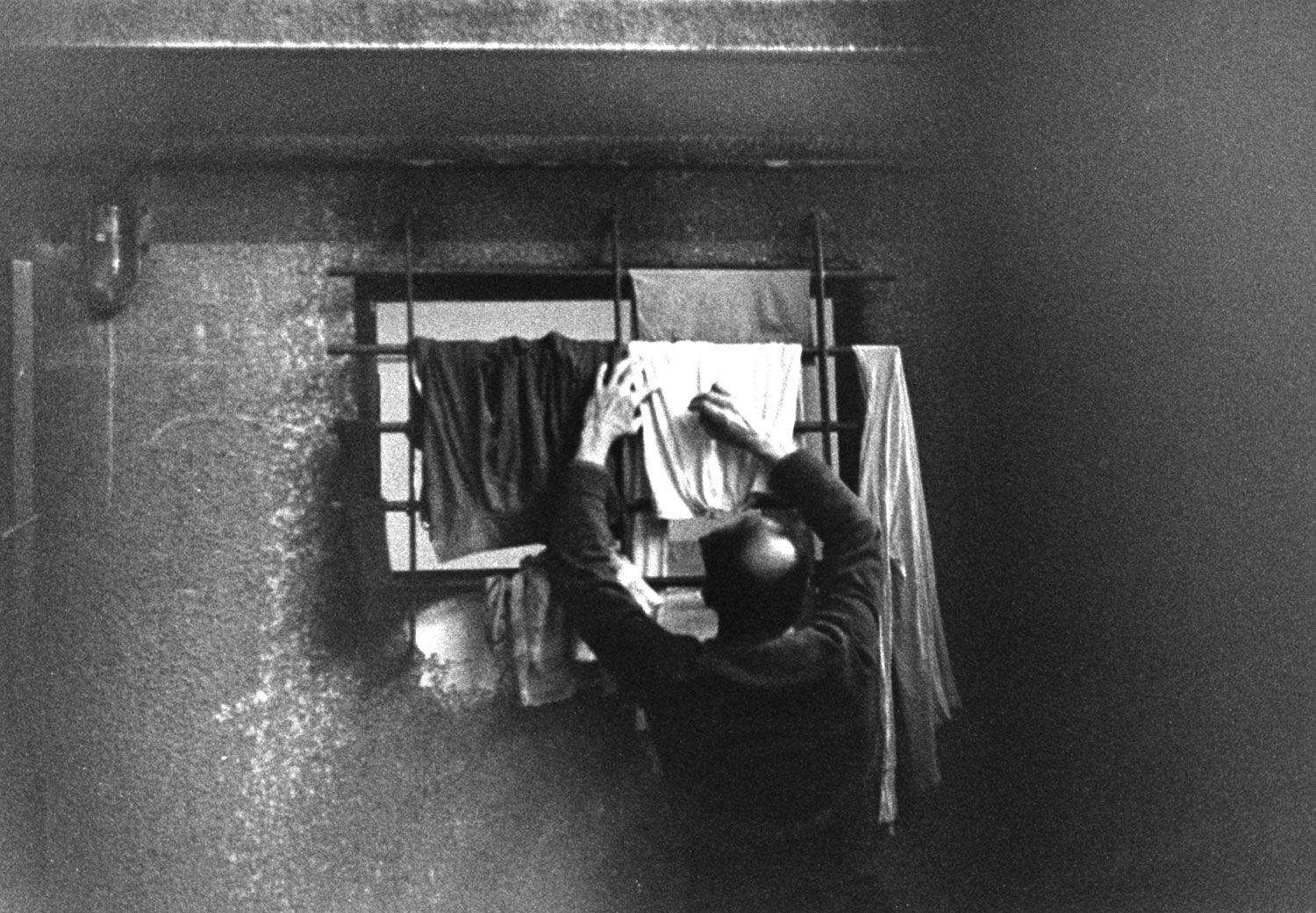

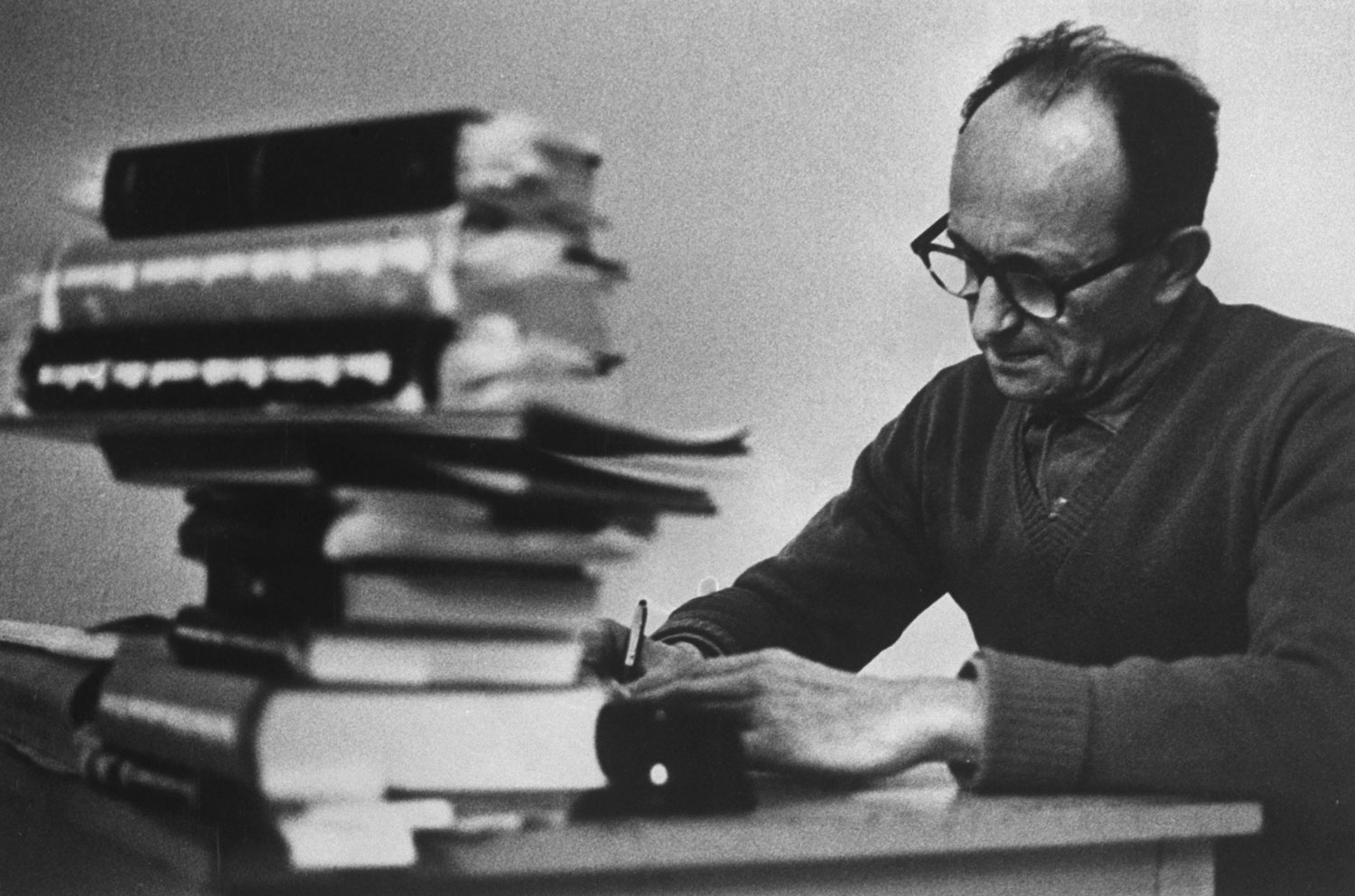

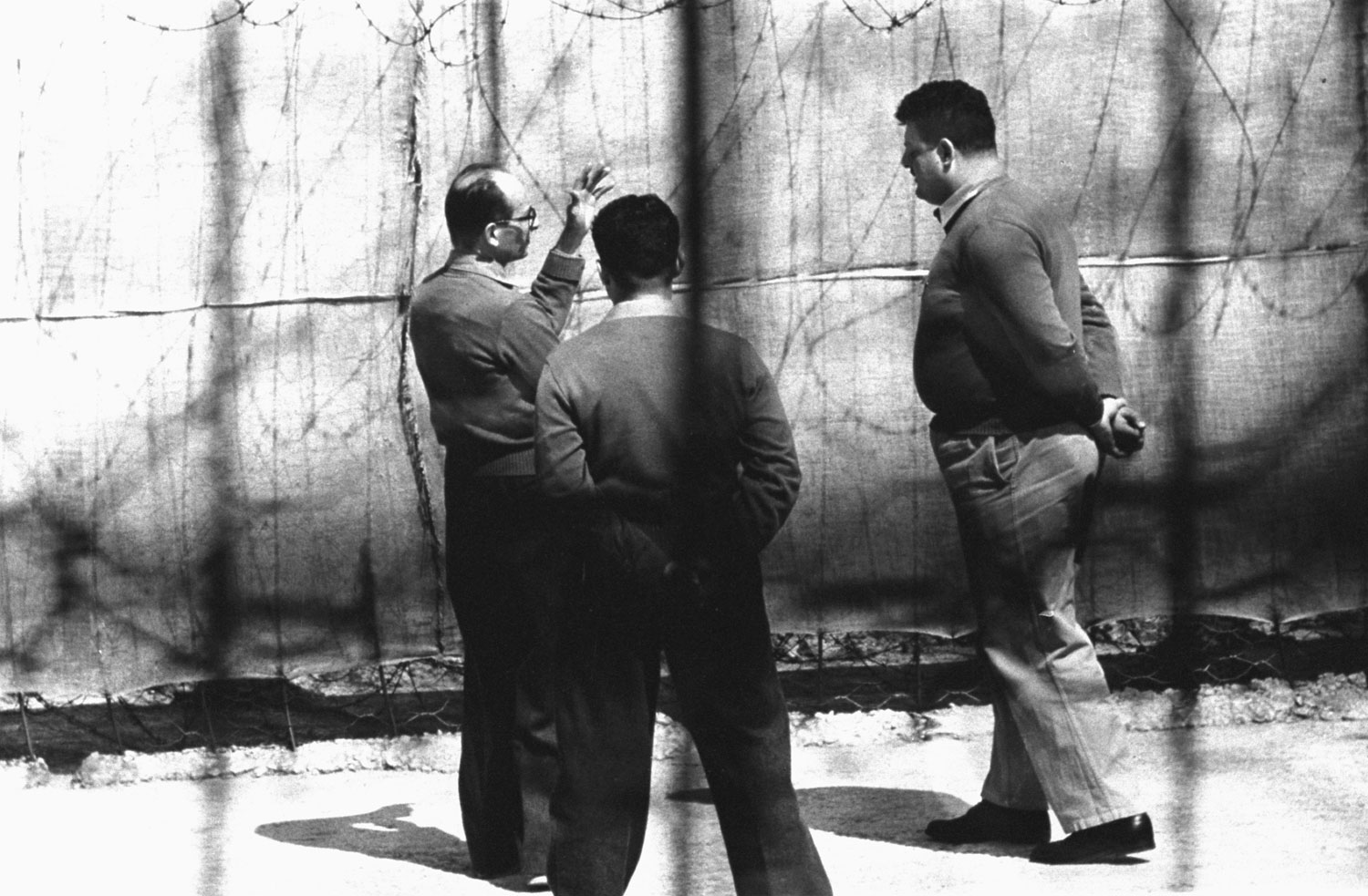

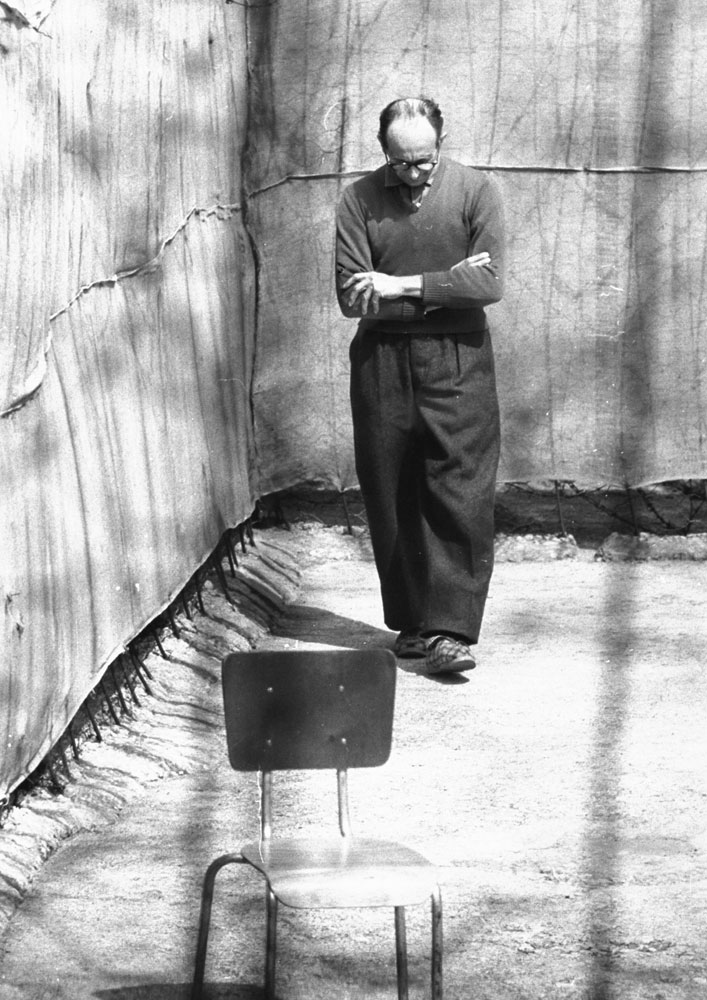

Here, more than five decades after his May 1962 execution by hanging in Israel after a 14-week war-crimes trial, LIFE.com presents pictures of Eichmann in prison: raw, strangely intimate photographs by Gjon Mili chronicling the “arch war criminal” (as LIFE put it) engaged in the most quotidian of pursuits — reading, writing, washing, eating — all the while fully aware, as most of the world was fully aware, that what awaited him at the end of the trial was a noose.

But before Eichmann’s trial even began, the controversy around his capture and arrival in Israel was intense. He was snatched in May 1960 by “Israeli nationals” (translation: Mossad agents) from Argentina, where he’d been living as a fugitive for 16 years, and carted to Israel to answer for his role in the Holocaust before and during the Second World War. Eichmann’s kidnapping was criticized — and is still criticized, by some, to this day — as a violation of the sovereign rights of a member state of the United Nations. But when, after frenzied back-room negotiations, Israel and Argentina issued a joint statement in August 1960 laying the matter to rest, Eichmann’s fate was effectively sealed.

As LIFE reported to its readers in its April 14, 1961, issue, in which some of the pictures in this gallery first appeared:

Once in a while some great man becomes the symbol of the era in which he lived. Less often one man becomes the symbol of a quality of his era — of its good or evil, its reason or madness. Such a man is Adolf Eichmann, the Nazi, a symbol of the hatred and unspeakable hideousness of Hitler’s Germany.

Here he is in this dramatic study — the world’s first intimate look at a man who vanished 16 years ago and who for all those years was the hunted, almost faceless arch war criminal. As head of the Gestapo office for Jewish affairs, Eichmann had organized with ruthless efficiency transport systems which carried six million Jews to extermination centers. After the war the survivors of his “final solution” of “the Jewish question” sought him all over the world. They had little to go on but memories of the arrogant gaze, the polished Nazi boots. But they found him — last May, in Argentina, where Israeli agents dramatically (and illegally) kidnapped him.

Unveiled, he had the tense look of a jackal at bay. Says Webster of jackals: “They are smaller, usually more yellowish, and much more cowardly than wolves, and sometimes hunt in packs at night.” Hunt with the pack is what Eichmann says he did, in his memoirs previously published in LIFE — that is, he only “obeyed orders.” Now trapped, he appeared smaller and yellower than his legend. Stripped of the trappings of the brutal system he served, he had no strut.

This week he would go into a Jerusalem court with the eyes of the world on him to stand trial for crimes against the Jewish people and against humanity. The trial, which has been attacked on legal grounds both in and out of Israel, was partly for the benefit of young Israelis to whom his crimes are so many lines in a history book. But more was on trial than Eichmann the man. It was the whole Nazi generation which condoned, participated in or didn’t want to know about it.

More Must-Reads from TIME

- Donald Trump Is TIME's 2024 Person of the Year

- Why We Chose Trump as Person of the Year

- Is Intermittent Fasting Good or Bad for You?

- The 100 Must-Read Books of 2024

- The 20 Best Christmas TV Episodes

- Column: If Optimism Feels Ridiculous Now, Try Hope

- The Future of Climate Action Is Trade Policy

- Merle Bombardieri Is Helping People Make the Baby Decision

Contact us at letters@time.com