On the heels of the Season 2 finale of Showtime’s Masters of Sex, LIFE.com presents an exclusive essay by Thomas Maier, author of the book on which the series is based, looking back at the revolutionary work of Dr. William Masters and Virginia Johnson—as well as their intensely fraught personal relationship—through the lens of LIFE photos from 1966.

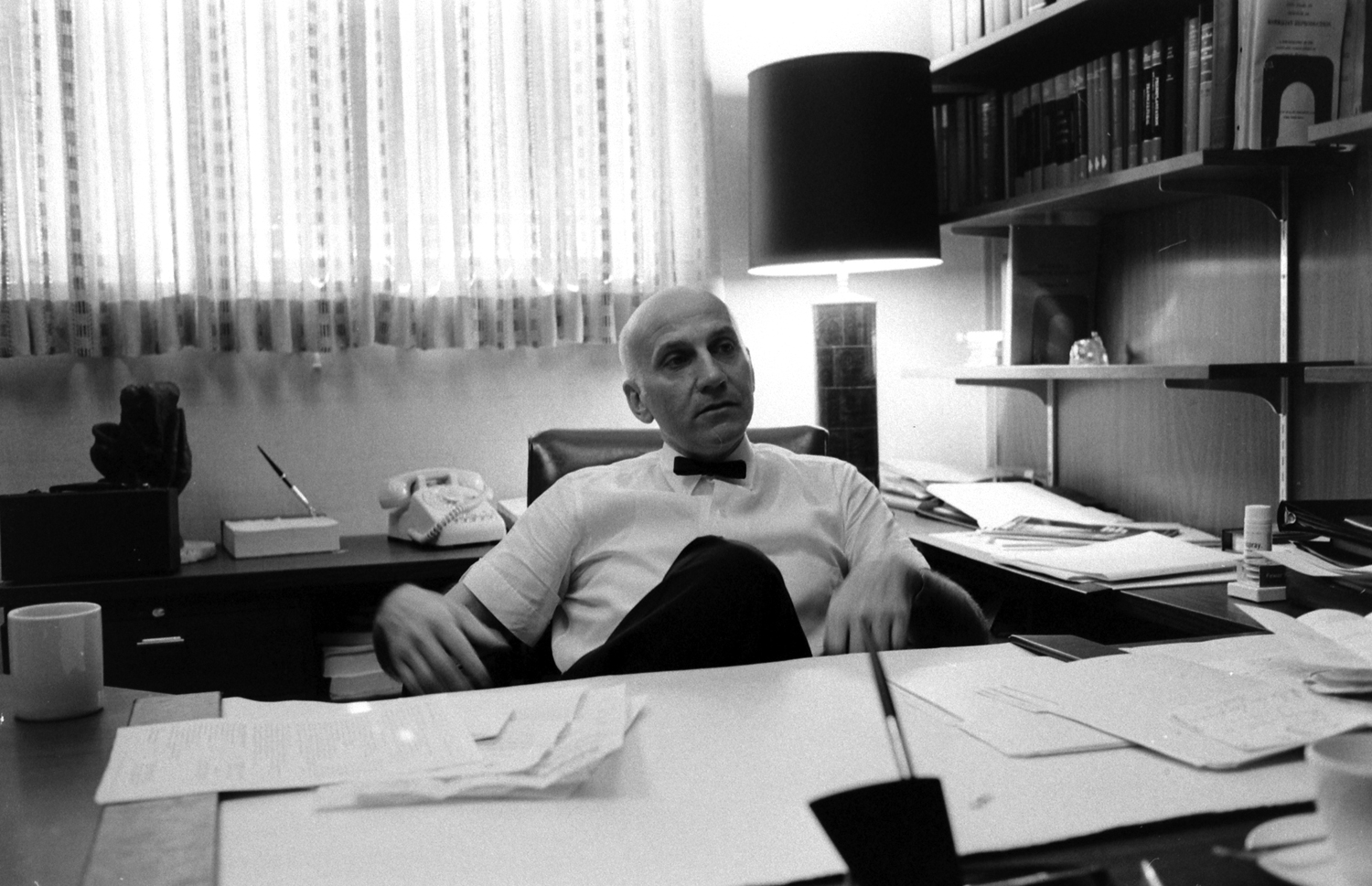

Before Kodachrome and color television came along, reproducing the world in all its countless hues, most people encountered the famous and the notorious in black and white photographs—gazing as if the pictures were glossy X-rays that could reveal the inner essence of men and women of note. Certainly the pictures in this gallery of the real-life Dr. William Masters and Virginia Johnson—whose life together is told in my book, Masters of Sex, the basis for the acclaimed Showtime series—holds that same fascination.

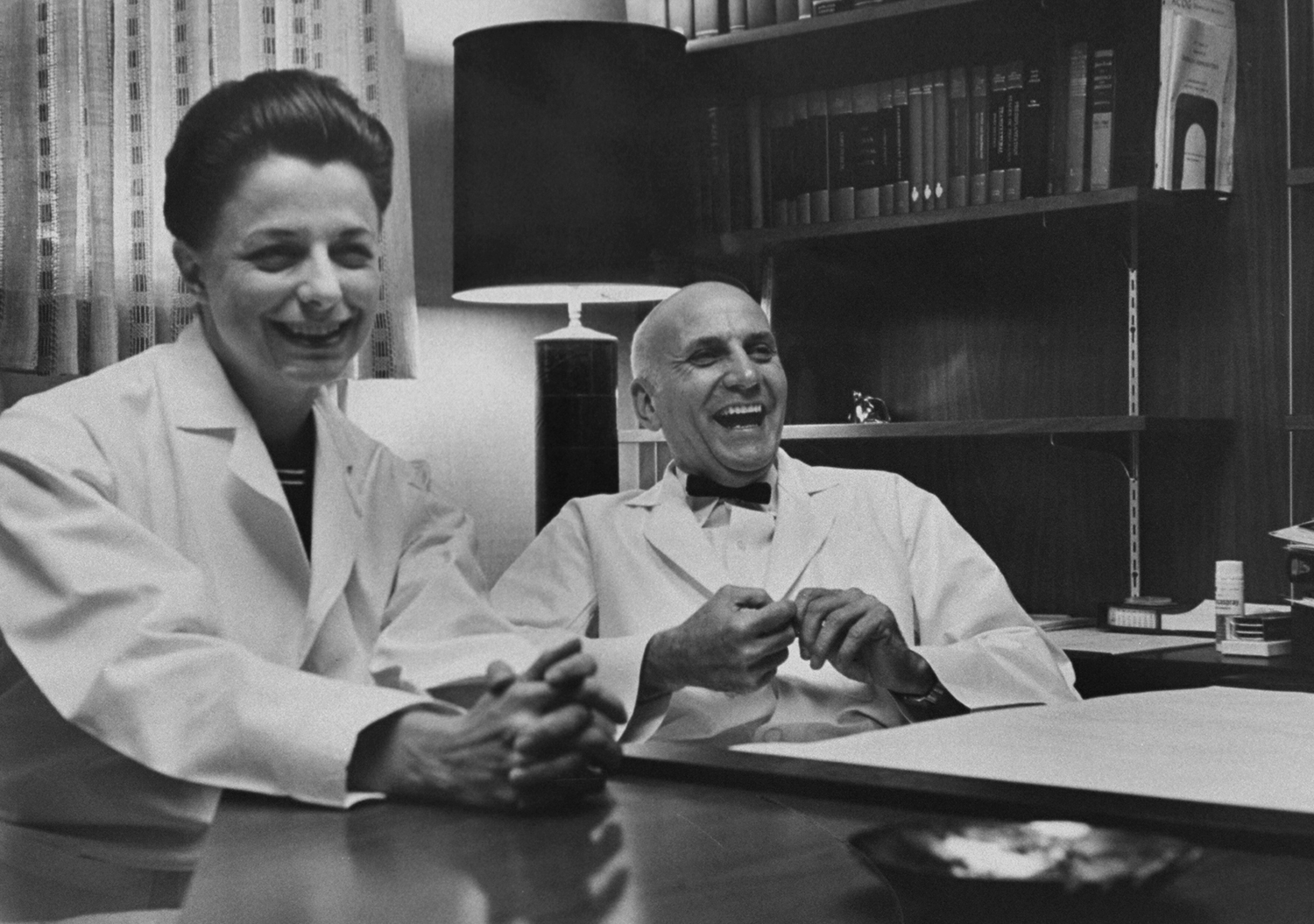

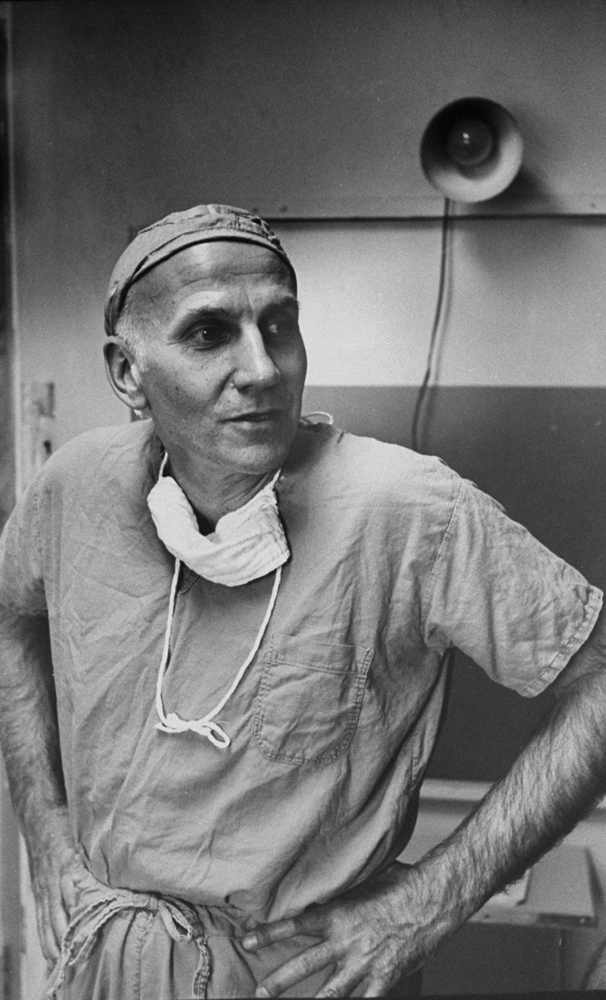

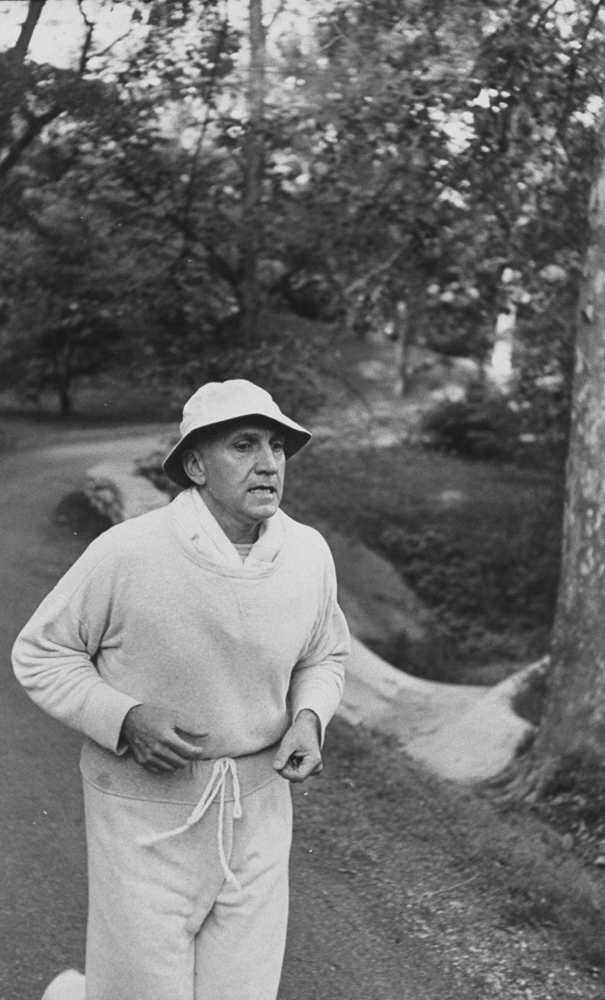

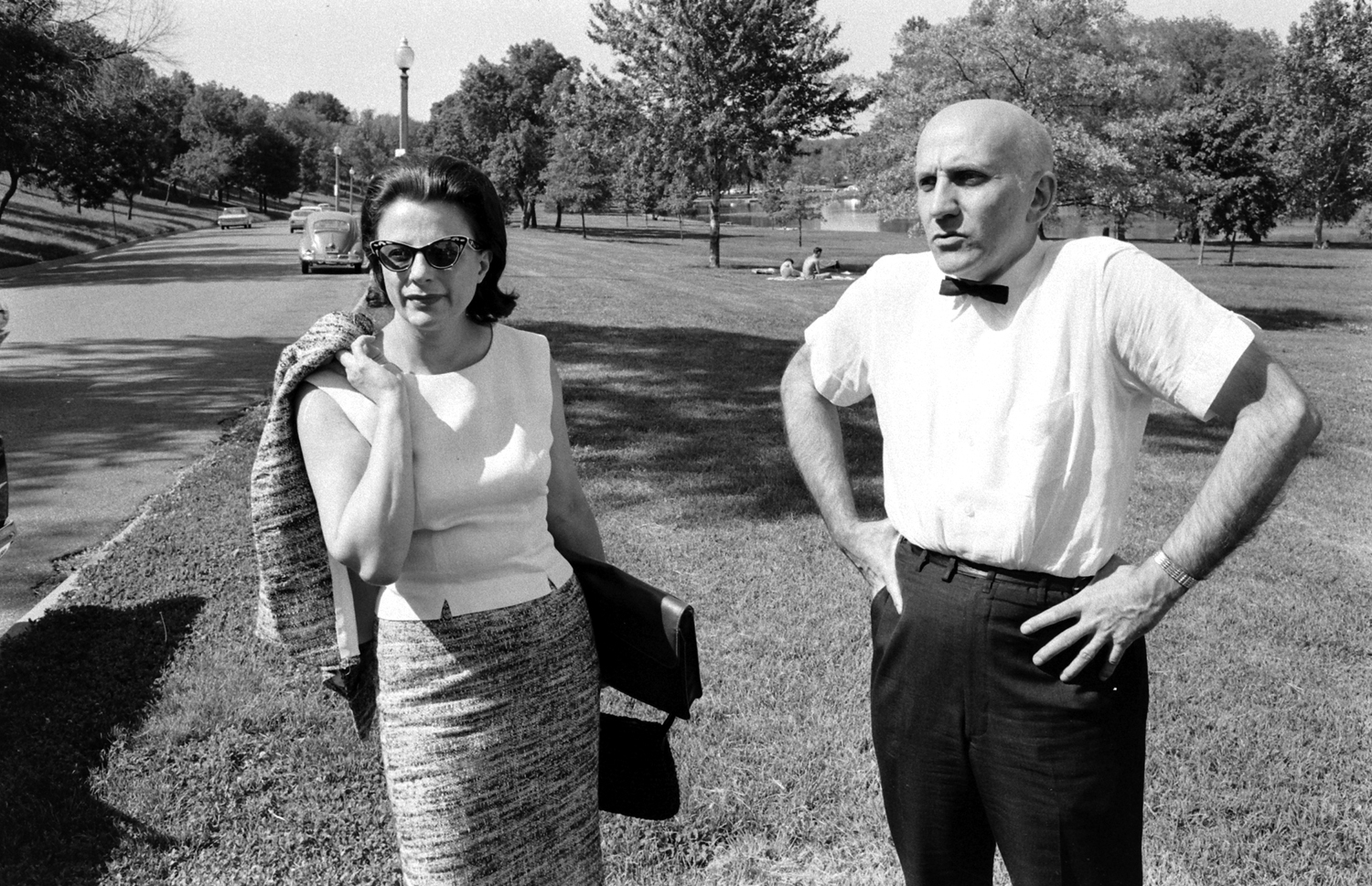

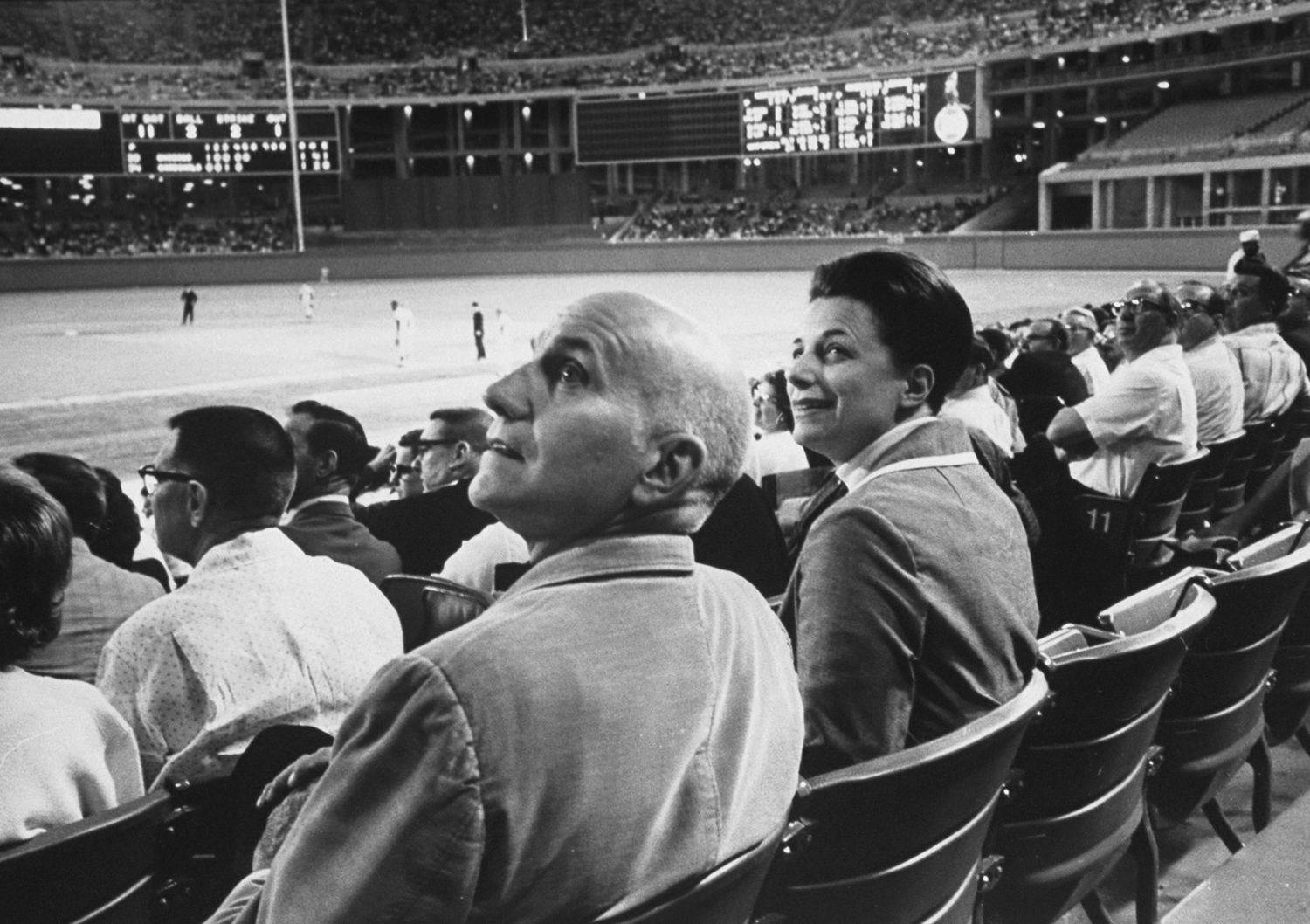

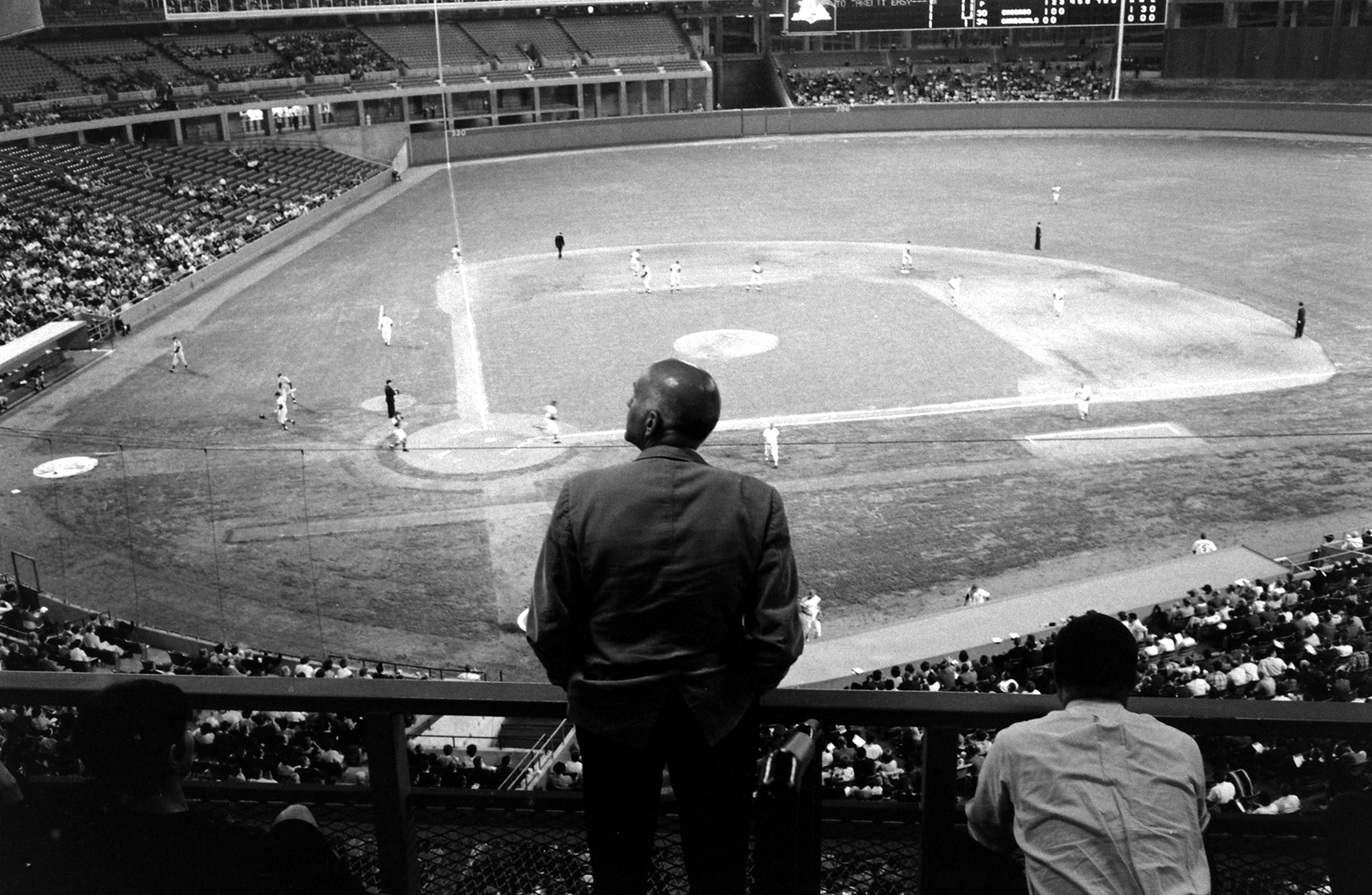

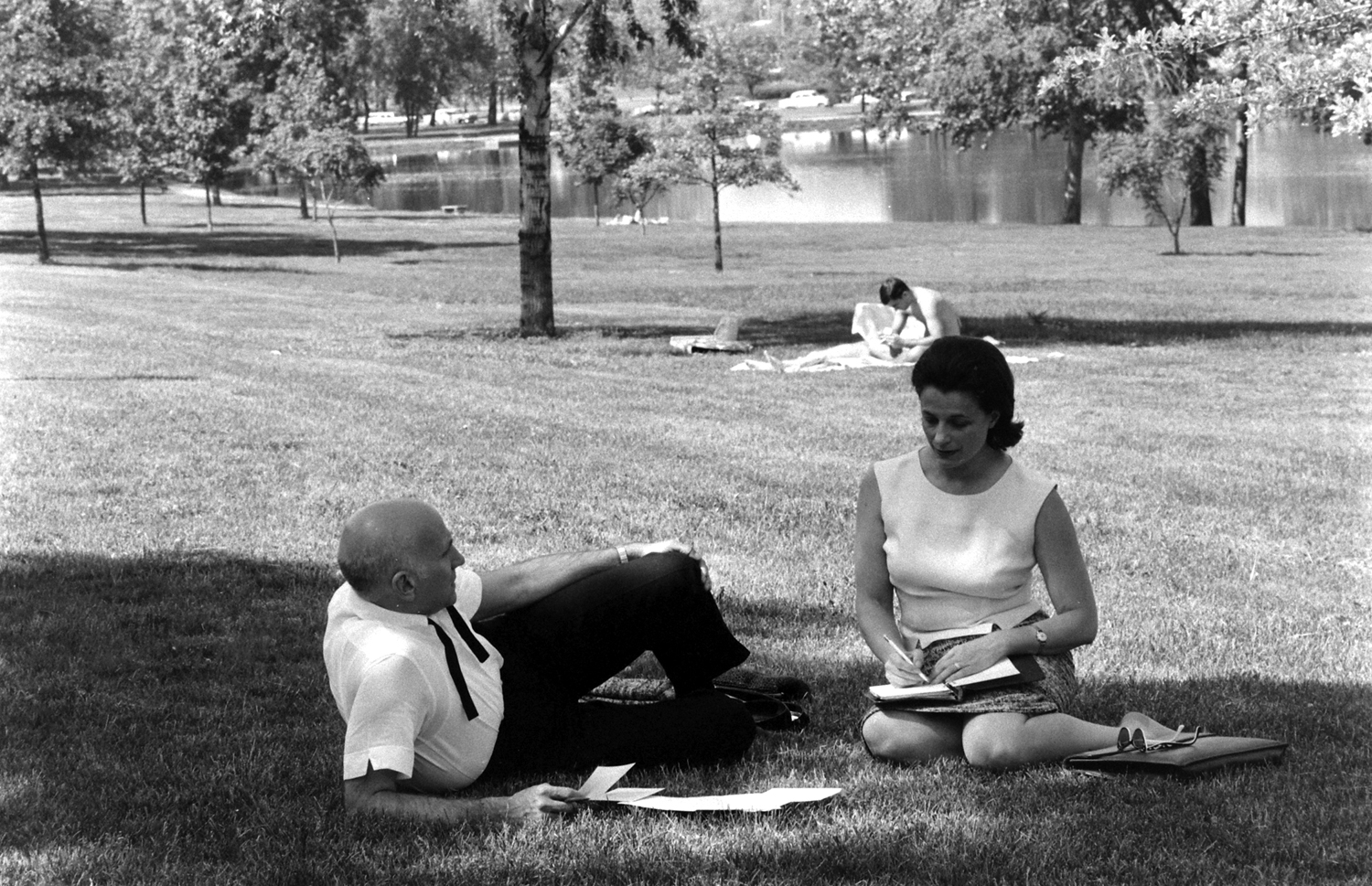

Though these photos are mostly posed, they do give a hint of the dynamic, creative chemistry between Masters and Johnson, whose studies of human sexuality at their St. Louis clinic were unique in their time. (In fact, their remarkable work was unique to any time. Experts say their sex research with volunteers couldn’t be done today in a hospital setting because of ethical restrictions.) These photos of Bill and Virginia capture a distinct turning point in their lives. After many years of secretly documenting how the human body responds during sex—and coming up with remarkably effective treatments for their patients—Masters and Johnson were suddenly famous with the publication of their first landmark book, Human Sexual Response (1966).

Their relationship was constantly in flux, and the pictures here project a number of different roles for Masters and Johnson—man and woman; powerful doctor and ambitious assistant; professional associates who were secret lovers; co-authors sharing the same byline on best-selling books; medical pioneers who found their muse and their license in each other, the sum of their partnership far greater than anything they could achieve on their own. Through the lens of these pictures, it is fascinating to consider how far Masters and Johnson’s life together had already progressed, and how many twists and turns still awaited them before their relationship would collapse in 1991.

Today, television is our most personal medium—far more so, arguably, than the movies and magazines of old—as our so-called “golden age” of narrative TV dramas wields an at-once greater impact and intimacy than ever before. Showtime’s interpretation of my book, for example, brings Masters and Johnson’s remarkable personal and professional story to life. It seemed the perfect canvas to capture both the audacity and nobility of Bill and Virginia’s work.

By design, Masters of Sex seems like no other television show. It is, after all, about what D. H. Lawrence called the “life urge,” about human intimacy and the search for meaning and understanding among the sexes, rather than another concoction that reflects society’s evident obsessions with death and violence. The show portrays women as equals, flesh and blood equivalents to men, at a time when American culture, at least, treated a female hospital worker like Virginia Johnson as a mere appendage or would-be courtesan. Using humor as well as drama, Masters of Sex dives headlong into the issues of misogyny and sexism, seeing them as lasting and pernicious civil rights issues. While so many TV shows dwell on violence, drugs, psychotic thugs and corrupt cops, “Masters of Sex” explores the human heart. Amid scenes of naked volunteers testing the boundaries of orgasm in the name of science, there are moments of yearning and even desperation among sexually dysfunctional couples—most of them married—seeking Masters and Johnson’s help in expressing themselves intimately.

It’s remarkable to me how television has pulled these pioneers from the dustbin of history, reminding us of the courage, daring and tensions implicit in their work. Particularly for young people, unaware of Masters and Johnson, it’s difficult to appreciate how so much has changed between the mid-’60s and today. But at the time they were becoming famous, their graphs, charts and photos of human sexual response—learning how the body worked so they could “fix” sexual problems with their therapy—were revolutionary.

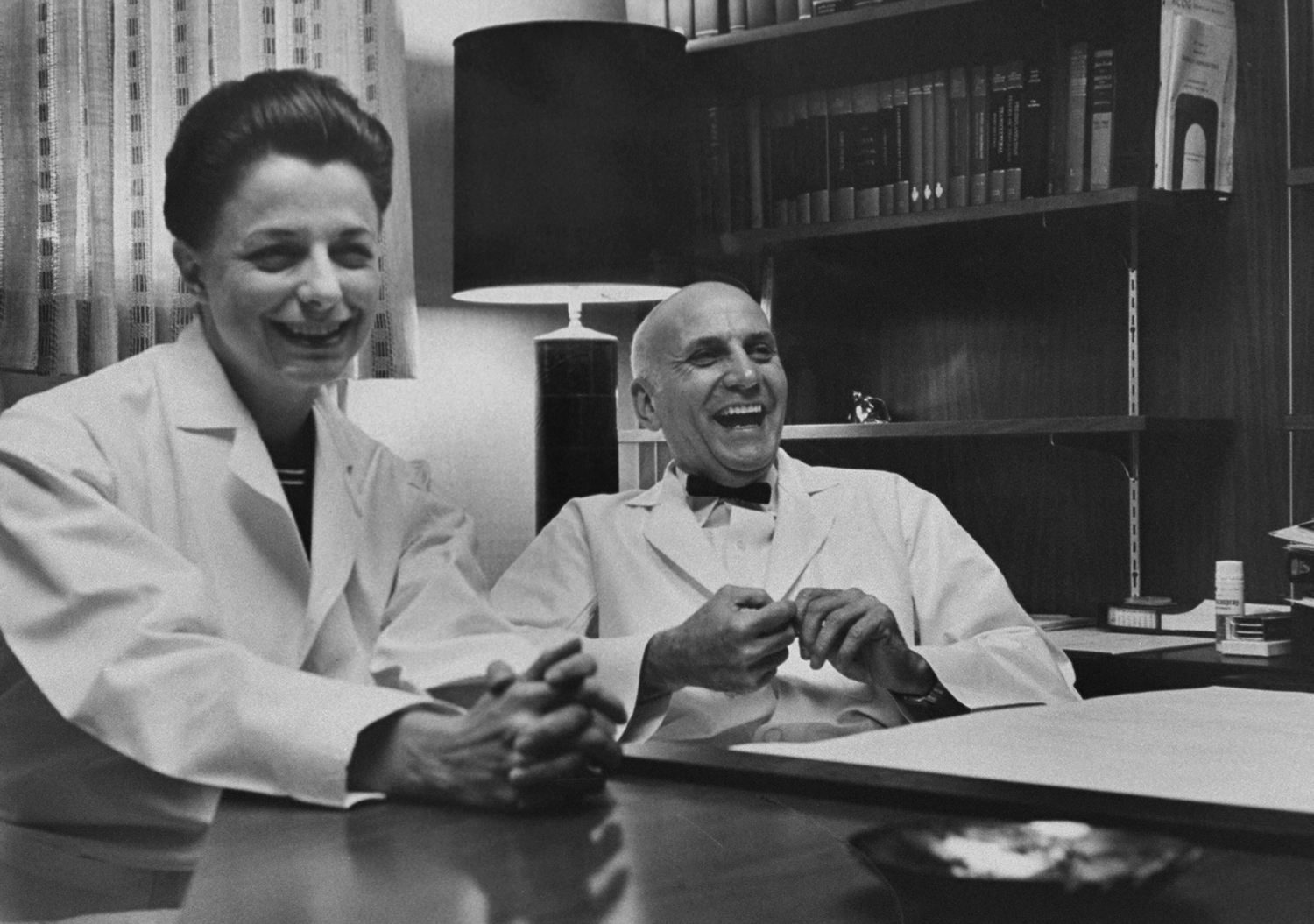

In a real sense, Masters and Johnson symbolized the triumph of modernity and medicine over religious taboos and cultural ignorance. Their “facts of life” felt far more definitive than ancient religious screeds or even Freud’s theories. Sex had left the church and entered the clinic. Instead of consulting with black-clad ministers or rabbis, Americans would rely on doctors in crisp white. At great risk to their livelihoods and reputations Masters and Johnson provided men and, particularly, women with the freedom and fundamental knowledge to make vital choices in their relationships, while highlighting medicine’s position at the forefront of social debates about human sexuality.

At its heart, though, you might say that Masters of Sex—the book and the show—is a postmodernist parable about the limits of science; how modern medicine can never truly understand our deepest, most intimate feelings. Masters’ and Johnson’s study of hormones and electrocardiogram impulses could deepen our understanding of our own skin and corpuscles, but alone it could not touch the soul, the essence of the bond between two people.

By the 1970s, Masters and Johnson themselves acknowledged this limitation of science. Ironically, the culture that inherited America’s sexual revolution is today awash in ads for Viagra and online porn, while evidently as clueless—maybe more clueless—about love than their grandparents in the 1950s.

Masters’ and Johnson’s own relationship harkened back to eternal questions between men and women. After all, was Bill’s willingness to place Virginia on an equal plane—creating the celebrated Masters and Johnson partnership—the act of a subtle manipulator willing to exploit anyone in search of a Nobel Prize? Or was giving Virginia a chance to share the limelight, to encourage her extraordinary abilities and insights, an act of true love? Years after I first spoke with both of them, I still wonder. And apparently so did Virginia Johnson, in her own way.

Months after its publication, I called Virginia for her eighty-fifth birthday and we got to talking about my book.

She said there were plenty of parts about her personal life where she flinched, parts about the sex experiments where she laughed remembering their boldness, and other parts, like Bill’s later theories on gay conversion based on her therapy, where she had genuine remorse. She said she still hoped to write a memoir herself someday.

Then the conversation turned to Bill and whether she ever really loved him. (Masters died in 2001, before I began writing my book, though I had interviewed him briefly in 1994). During my research, Gini insisted she never did love Bill; perhaps their relationship was too complex for such a simple term.

Even now, more than a decade after their divorce and Bill’s death, she seemed obsessed, infuriated, thrilled and immensely proud of their time together.

I suggested she was still in love. For the first time, her tone sounded different.

“I guess so,” she said, wistfully.

Their relationship never seemed to end, even in death. In July 2013, Virginia Johnson died at age 88, only a few weeks before the premiere of Showtime’s “Masters of Sex.” As I look at these photos, I’m reminded once again of our conversations together, about the passion and drive in their lives, and about the lasting enigma of Masters and Johnson.

See more about Masters of Sex at Showtime online. Buy Thomas Maier’s Masters of Sex: The Life and Times of William Masters and Virginia Johnson, the Couple Who Taught America How to Love at Amazon or barnesandnoble.com.

More Must-Reads from TIME

- Donald Trump Is TIME's 2024 Person of the Year

- Why We Chose Trump as Person of the Year

- Is Intermittent Fasting Good or Bad for You?

- The 100 Must-Read Books of 2024

- The 20 Best Christmas TV Episodes

- Column: If Optimism Feels Ridiculous Now, Try Hope

- The Future of Climate Action Is Trade Policy

- Merle Bombardieri Is Helping People Make the Baby Decision

Contact us at letters@time.com