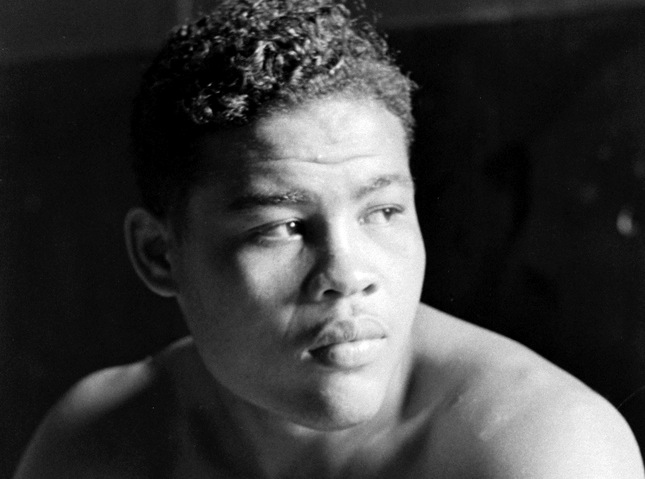

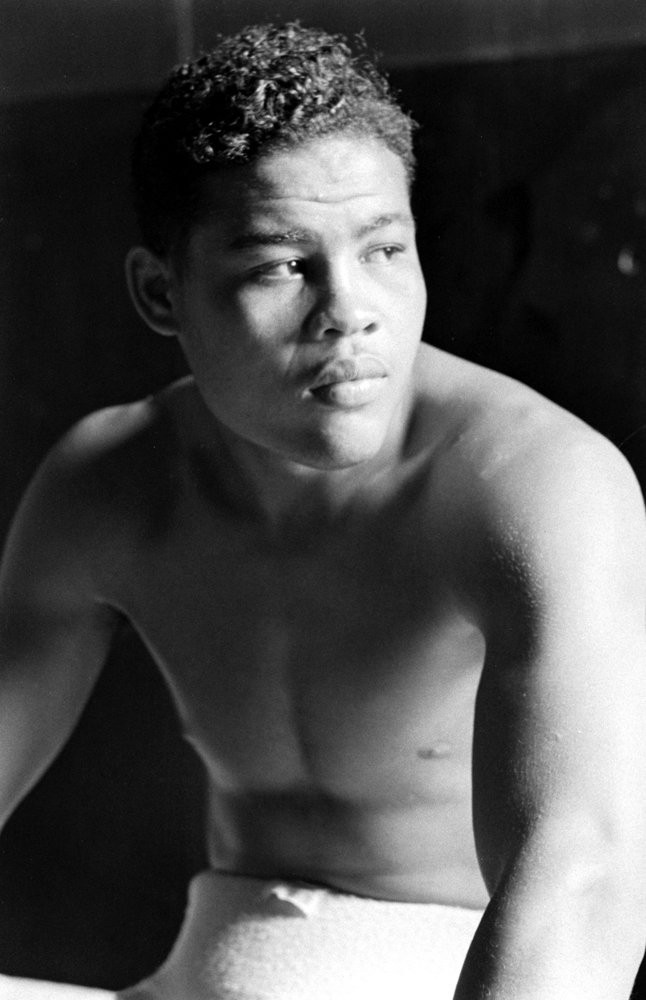

Literally and figuratively, Joe Louis was huge. Yes, he was physically imposing; at 6′ 2″ and with a 76-inch reach, he was a big fighter by any standard. But in an age when baseball, boxing and horse racing were America’s “Big Three” sports, he was rivaled as a cultural and athletic icon only by the likes of Ted Williams and Joe DiMaggio and by Triple Crown-winners like Citation, Whirlaway and War Admiral.

Here, on his 100th birthday — Louis was born May 13, 1914, in Lafayette, Ala. — LIFE.com celebrates the man known to several generations as the “Brown Bomber.” (Less savory — or more racist, depending on one’s point of view — nicknames included the Mahogany Mauler and the Safari Sandman, the latter evidently meant to tout Louis’s “lights out” punching power.)

Louis was the first African-American embraced across the country not merely as an athlete and celebrity, but as a patriot — he enlisted in the Army early in the Second World War, in 1942, and along with other fighters staged boxing matches all over the world, eventually performing for more than two million American troops.

In the ring, meanwhile, when fighting for real — and not merely to raise the morale of his compatriots — Louis was, for years, unstoppable. Between 1937 and 1949, when he held the heavyweight crown for a record 12 years, Louis successfully defended his title 25 times — another pro boxing record. He is universally lauded as one of the top heavyweights of all time, and for many boxing fans and experts only Muhammad Ali might lay legitimate claim to being the better fighter. (For his part, Ali reportedly belittled Louis as an “Uncle Tom” — an ugly habit that the former Cassius Clay indulged in for much of the 1960s and 1970s.)

Louis’s fights with Max Schmeling, Billy Conn and others are among the sport’s most legendary, while his role as a quiet symbol of black pride made him one of the seminal figures of the burgeoning civil rights movement.

As with so many fighters, Louis’s later life was marked by illness, financial woes (he was famously generous with the millions he earned in the ring) and indignities large and small — including a short stint as a professional wrestler. But he often received unasked for help from the many friends he made and the admirers he won throughout his long career, and his last years were not defined by the sort of squalor that accompanies so many boxers’ ends.

When Louis died in 1981, at the age of 66, he was buried, with full military honors, in Arlington National Cemetery. His great rival in the ring — and, later in life, his dear friend — Max Schmeling, was a pallbearer.

— Ben Cosgrove is the Editor of LIFE.com

More Must-Reads from TIME

- Why Trump’s Message Worked on Latino Men

- What Trump’s Win Could Mean for Housing

- The 100 Must-Read Books of 2024

- Sleep Doctors Share the 1 Tip That’s Changed Their Lives

- Column: Let’s Bring Back Romance

- What It’s Like to Have Long COVID As a Kid

- FX’s Say Nothing Is the Must-Watch Political Thriller of 2024

- Merle Bombardieri Is Helping People Make the Baby Decision

Contact us at letters@time.com