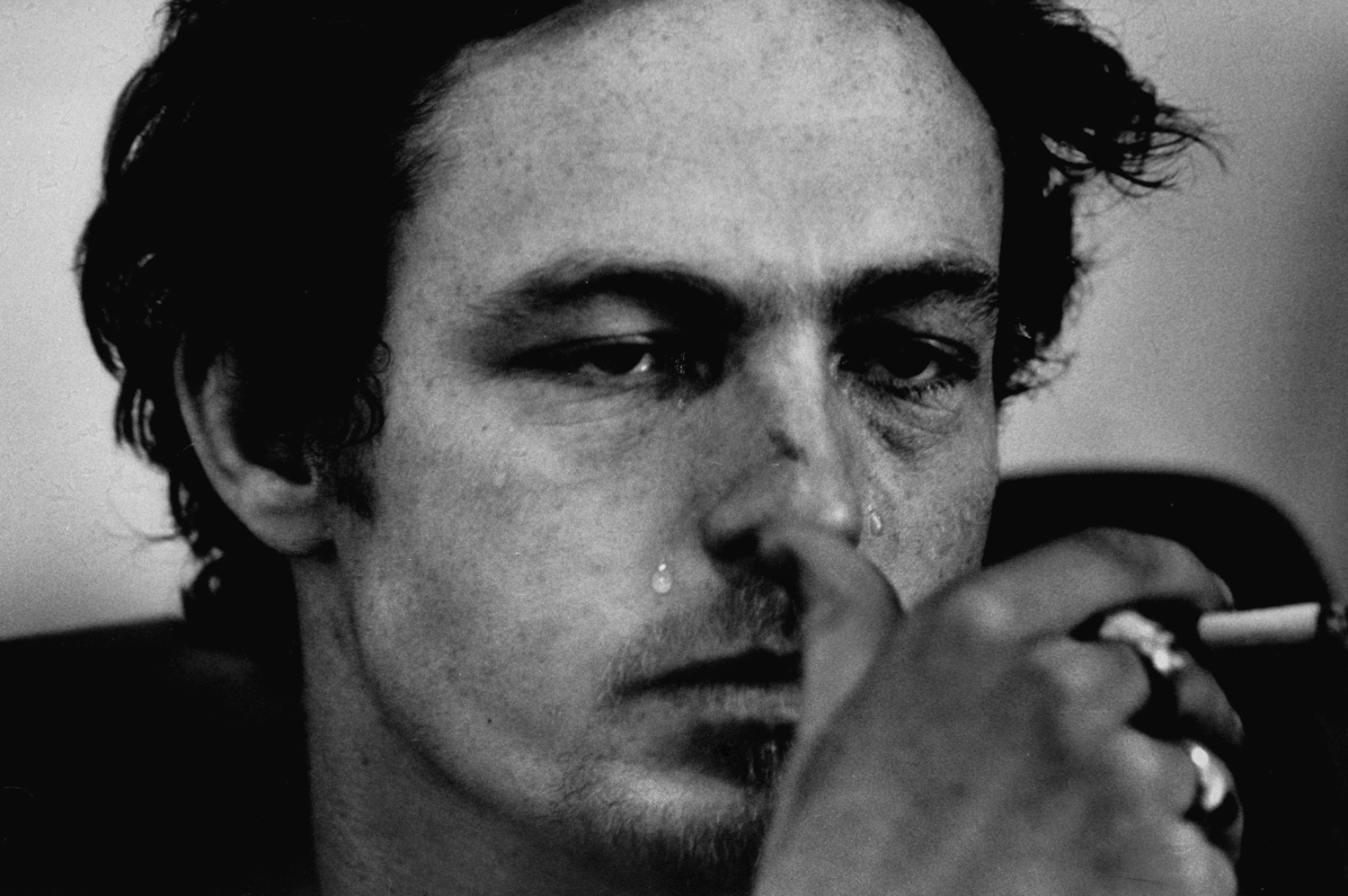

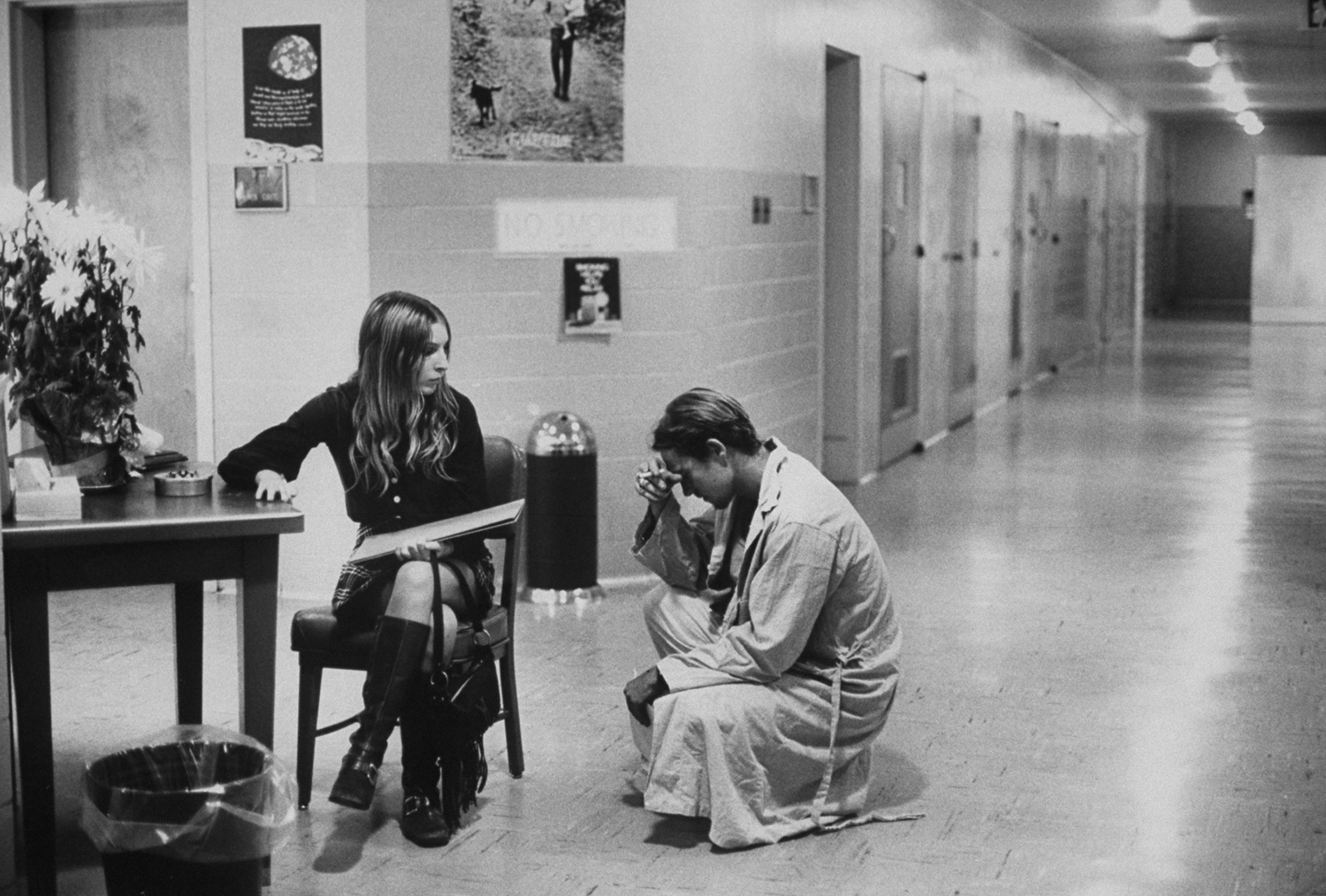

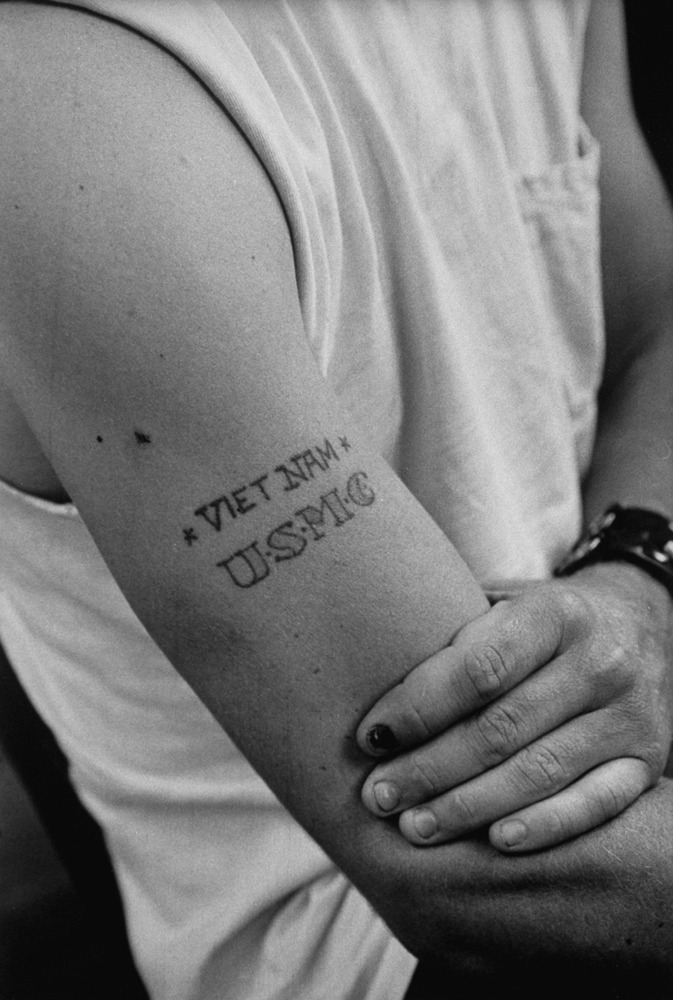

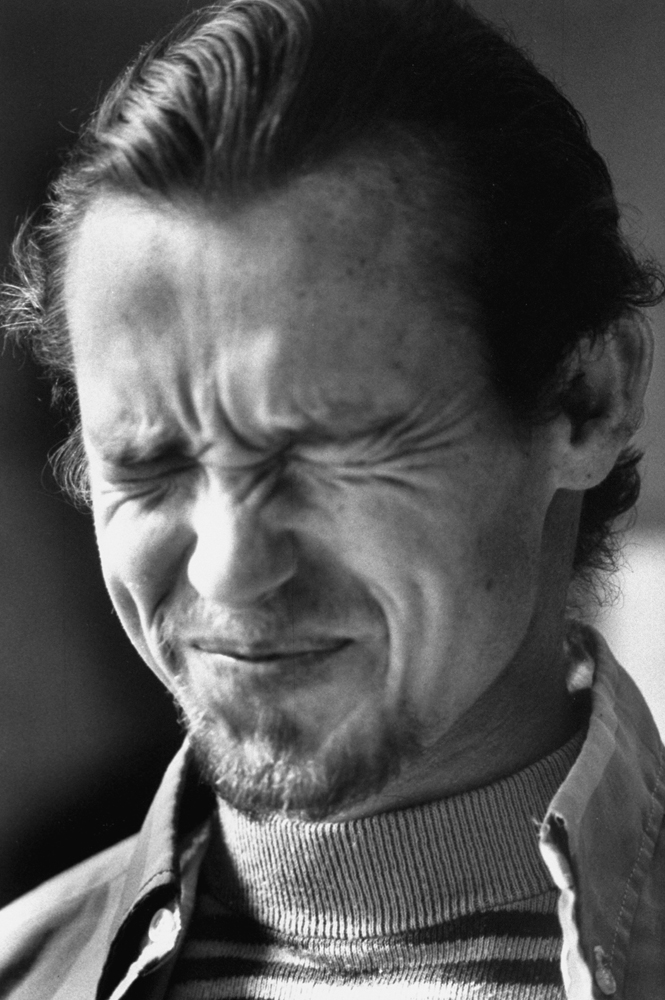

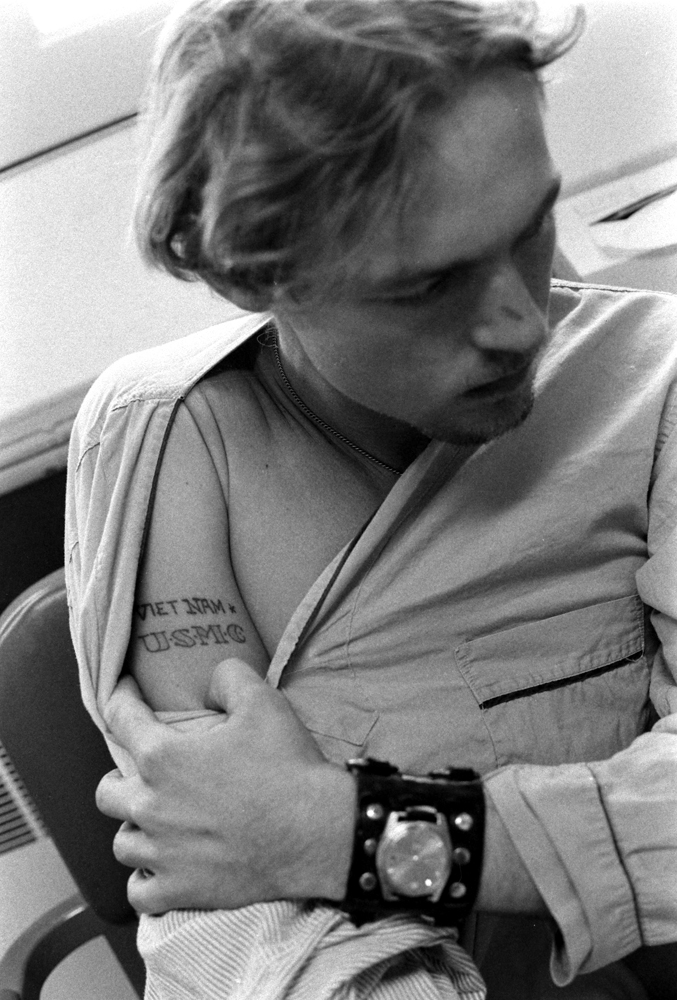

Sonny Martin was just 23 when he returned home from Vietnam with a grim souvenir of his stint in uniform: a heroin addiction. Martin turned to the drug to help stave off the memory of his time in Southeast Asia, where he had bribed villagers for information that would help him identify and “eliminate” Viet Cong collaborators. Back in the States, he found few people willing to help heal the invisible wounds that remained from his time in that brutal war.

“I had to keep it all inside,” Martin said in a July 1971 LIFE magazine story that illuminated the struggles — and addictions — short-circuiting so many veterans’ return to civilian life. According to the LIFE article, “the number of addicts is still not confirmed. Congressman Robert Steele (R-Conn.) and many returning veterans estimate that 15 percent of the men in Vietnam are hooked on heroin. The military claims the figure is 2 percent.” Whatever the actual numbers, it didn’t help that the drug was so easy to find: just two bucks would secure a fix of high-grade smack — a high that, for a while, blunted the anxiety, shock, and loneliness that defined so many veterans’ post-war lives.

Here, on the heels of recent reports about the enormous difficulties (joblessness, horrific suicide rates and more) facing American veterans of the wars in Iraq and Afghanistan, LIFE.com recalls that long-ago magazine article, and the all-too-familiar stories of young men struggling to put their lives back together after serving their country in a divisive, seemingly endless conflict.

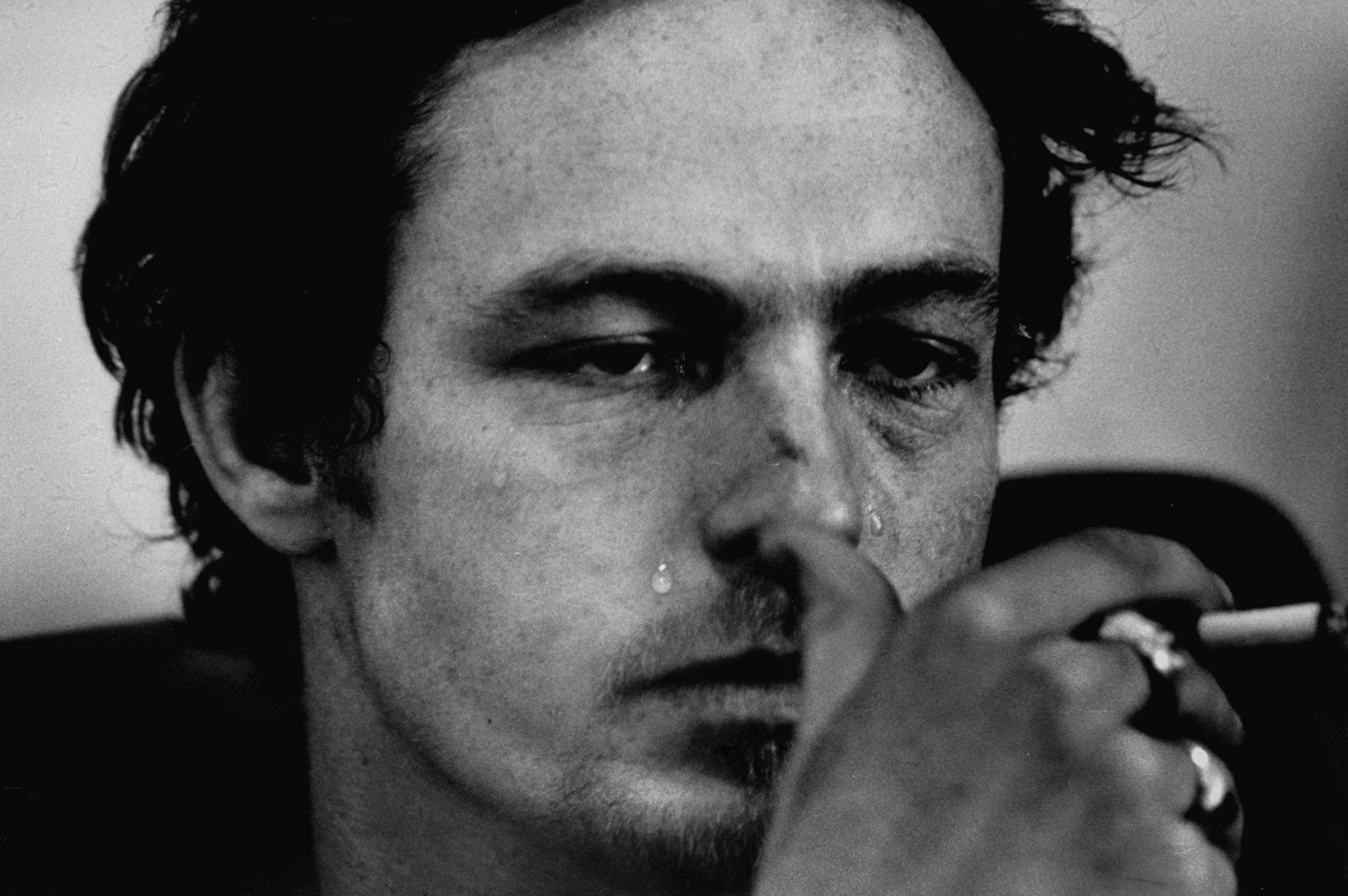

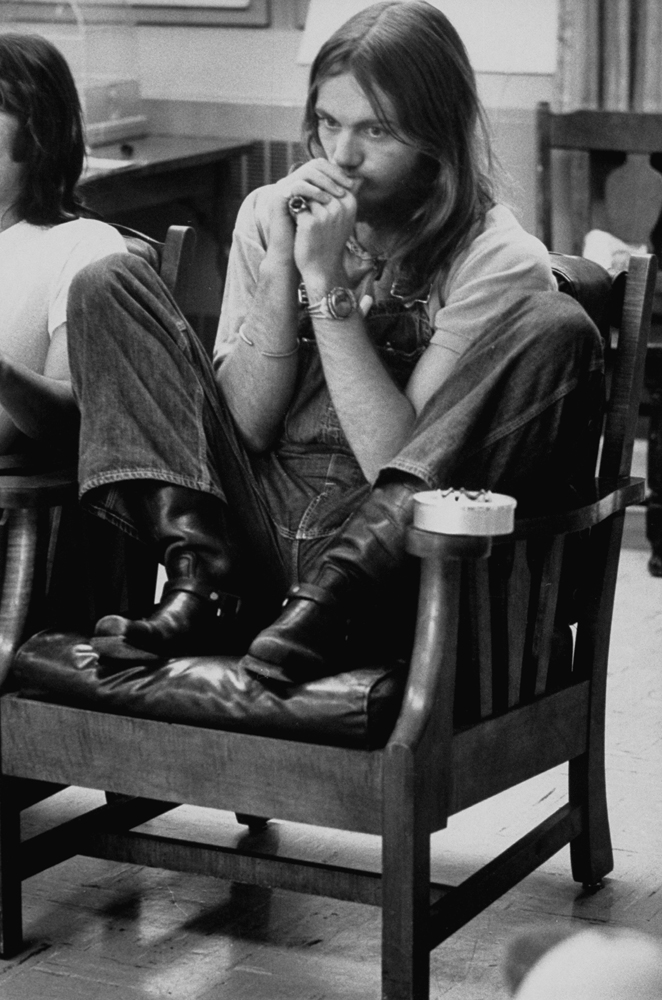

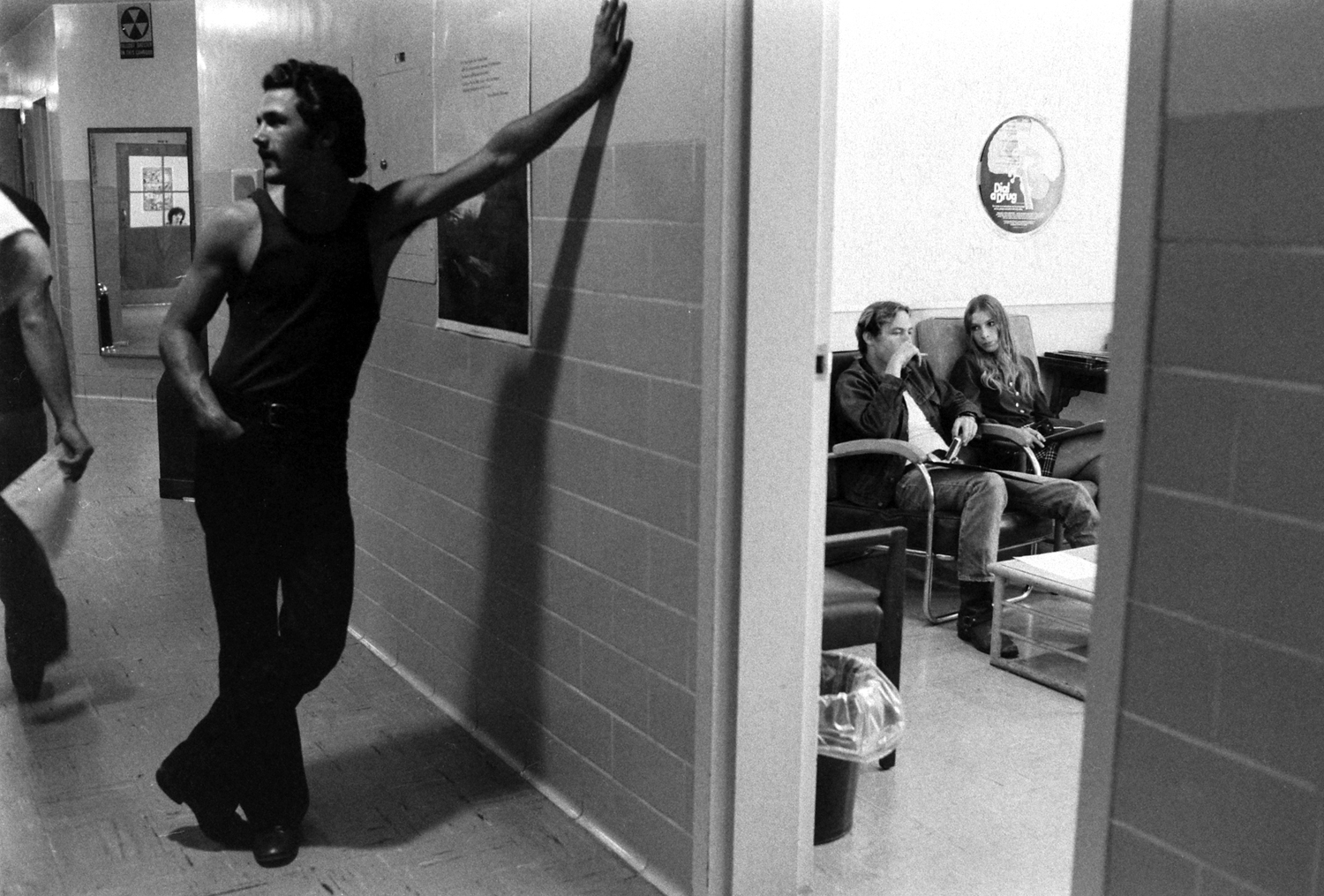

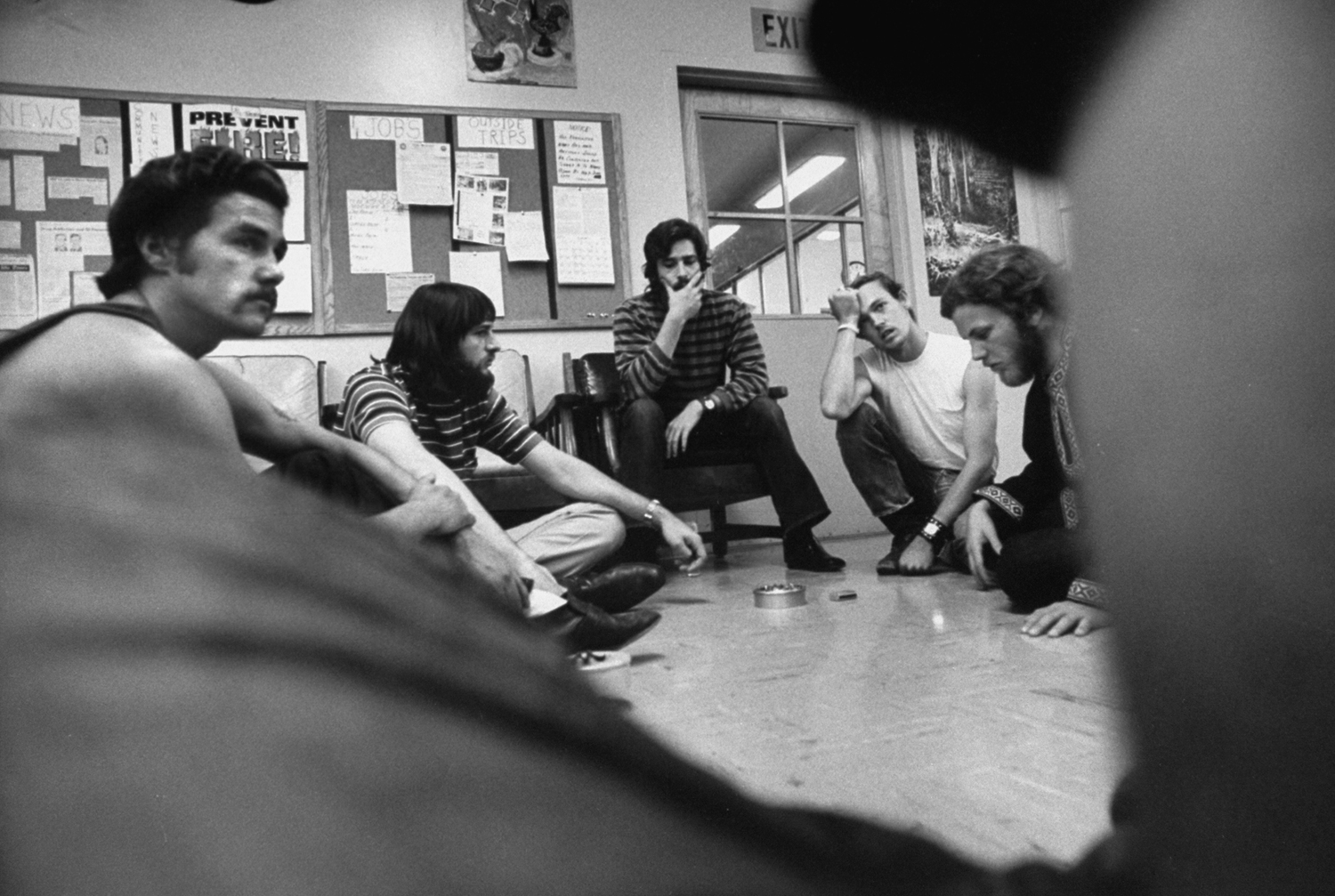

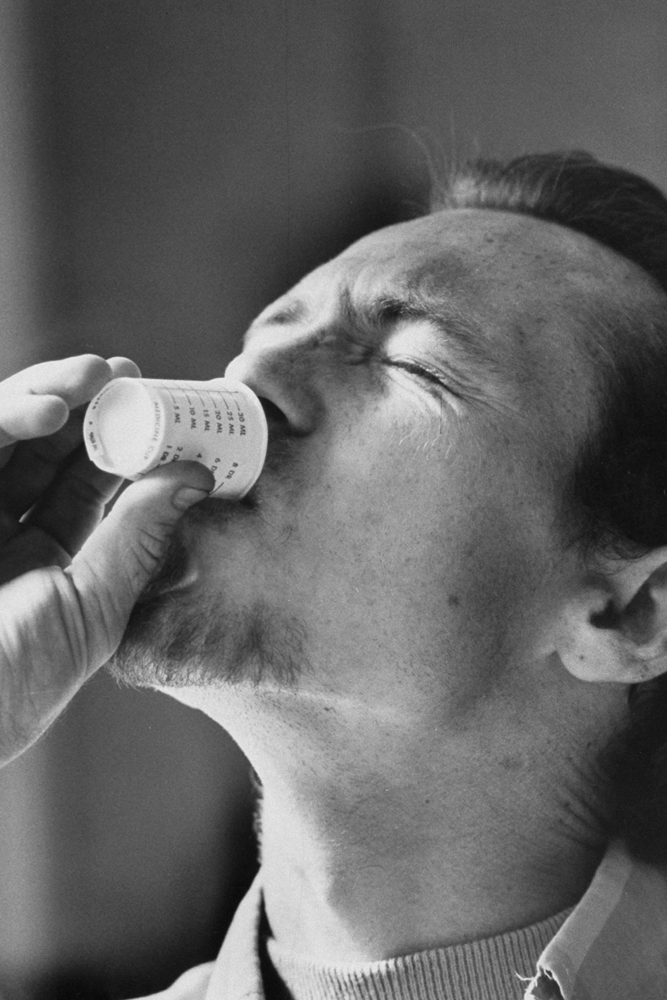

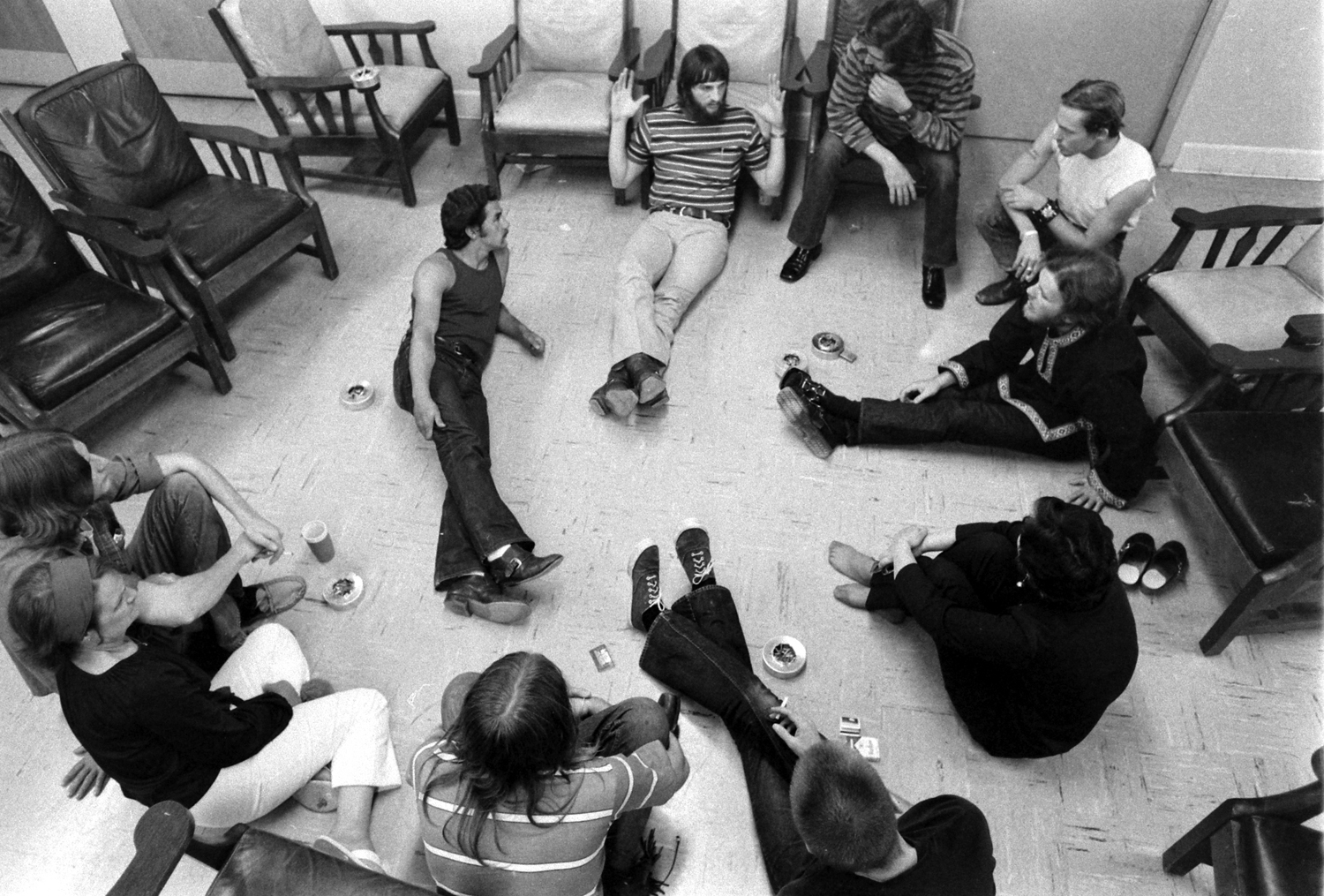

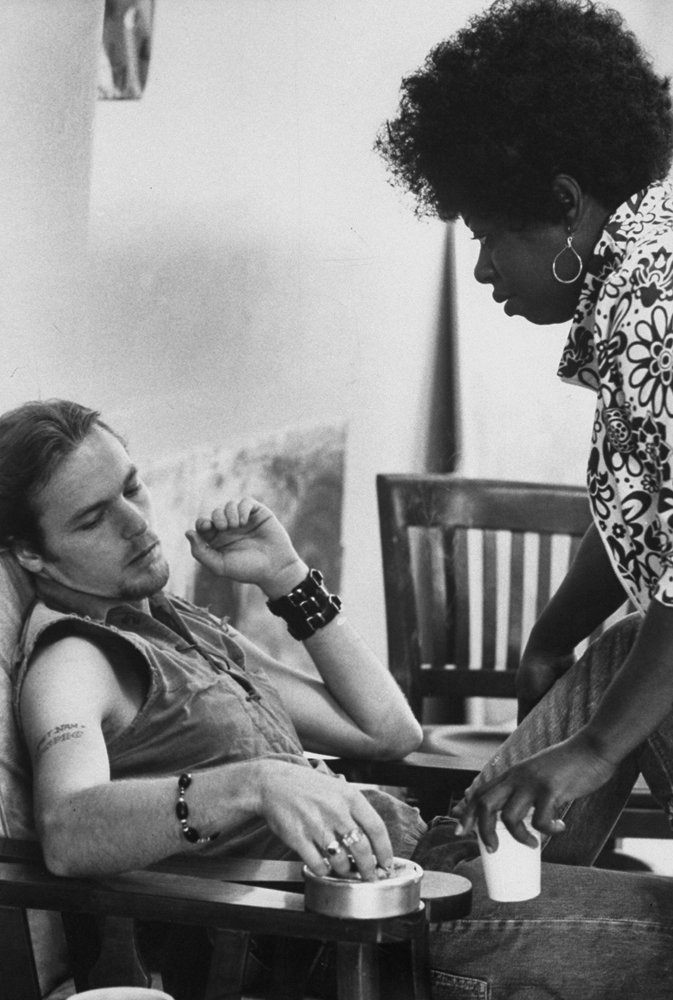

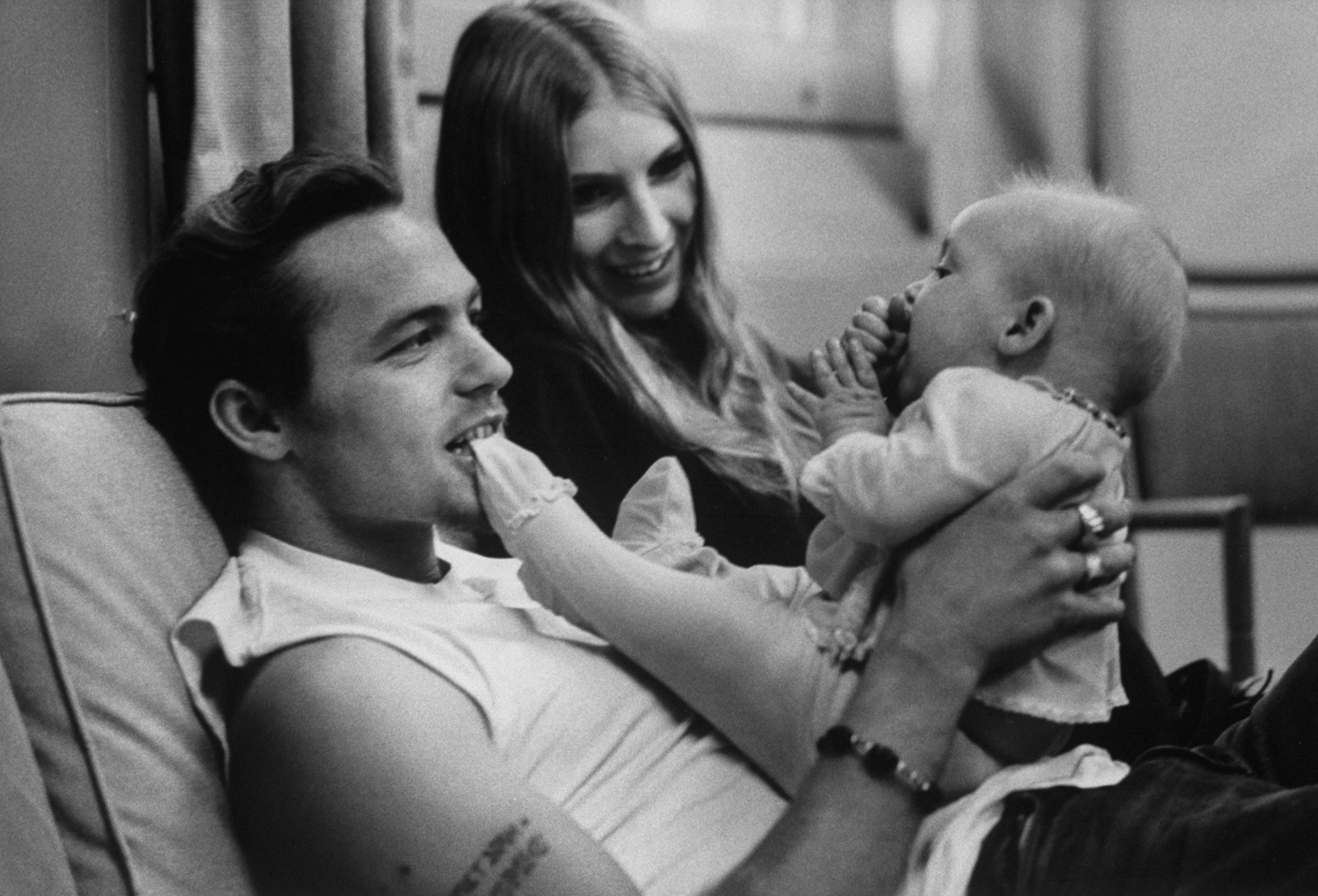

In 1971, addicted veterans who wanted to kick their heroin habit could check into places like Ward 4B2 of the Palo Alto Veterans Administration Hospital in California. There, doctors and nurses used the synthetic opiate methadone to “buy them time” while experimenting with one-on-one and small-group therapy sessions, urging the men to turn their problems inside out and tackle them head on. But veterans couldn’t just walk into Palo Alto and hope for a cure: they had to demonstrate a genuine commitment to their own recovery. That meant tough times for men like 22-year-old Dan Patterson (see gallery above), who snorted heroin on a trip to town after he’d been admitted to the Palo Alto program. The doctors and nurses voted: he was out. He could come back when he was serious about helping himself.

Hoping to see more places like Ward 4B2, in 1971 the Nixon administration set aside $14 million to put 13 more programs in place before the end of the year. The new programs looked to Ward 4B2 for guidance; but 4B2 was, of course, very much still feeling its way forward. It wasn’t clear whether the drug-and-therapy combination could truly wean an addict off of both methadone — which is itself addictive — and heroin.

While today’s doctors, psychologists and therapists have a firmer understanding of mental health and substance abuse issues than many of their Vietnam-era colleagues did, there is still so much left to tackle to ensure more productive, stable lives for returning veterans. Sonny Martin and Dan Patterson were only two casualties in a long, long line of men and women who suffered, and continue to suffer, from a nightmarish grab bag of debilitating emotional, physical and psychological woes after leaving the service. The US Department of Veterans Affairs recently reported a 44 percent increase in suicide rates among 18- to 29-year-old male veterans between 2009 and 2011. Between 10 and 18 percent of troops serving in Afghanistan and Iraq return with post-traumatic stress, up to a quarter suffer from depression, and others engage in excessive alcohol and tobacco use.

In this photo gallery, LIFE.com remembers the intensely personal war waged by so many who returned from Vietnam — as well as the inner conflicts that plague veterans today in the aftermath of witnessing, up close and personal, humanity’s boundless capacity for brutality.

More Must-Reads from TIME

- Why Trump’s Message Worked on Latino Men

- What Trump’s Win Could Mean for Housing

- The 100 Must-Read Books of 2024

- Sleep Doctors Share the 1 Tip That’s Changed Their Lives

- Column: Let’s Bring Back Romance

- What It’s Like to Have Long COVID As a Kid

- FX’s Say Nothing Is the Must-Watch Political Thriller of 2024

- Merle Bombardieri Is Helping People Make the Baby Decision

Contact us at letters@time.com