It lasted less than three weeks, from Oct. 23 until Nov. 10, but the Hungarian Revolution that convulsed Budapest and the rest of Hungary in late 1956 sent shock waves through eastern and central Europe that reverberated for decades. More than a few historians, in fact, cite the popular revolt as the first rip in the Cold War’s Iron Curtain.

The general lineaments of the 1956 conflict are well-known: In the autumn of that year, hundreds of thousands of Hungarians, in cities and the countryside, rose up against occupying Soviet forces and, critically, against the country’s brutal, homegrown secret police, the State Protection Authority. For a few heady weeks, it seemed like the insurgents might actually push the Russians out altogether. By mid-November, though, the Soviet army had regrouped and launched an all-out assault on a nation that was, nominally, both an ally and a protectorate.

Roughly 3,000 Hungarian civilians—men, women, children—were killed during those three weeks. The uprising was crushed. But the ripples of the revolt—the Prague Spring in ’68, Poland’s Solidarity trade union movement in the 1980s and other rebellions, large and small—were wide-ranging, and long-lasting.

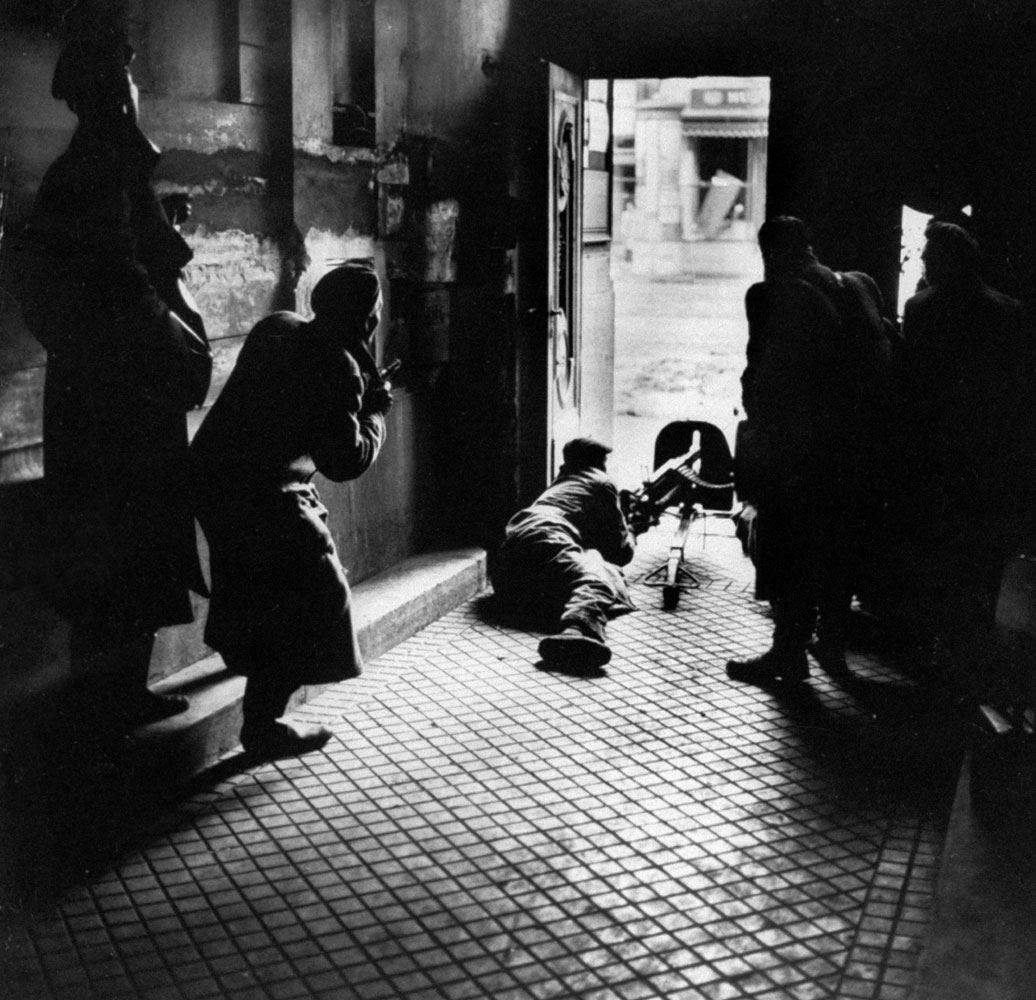

Here, LIFE.com recalls the events through photos made by the great Michael Rougier, a photojournalist whose pictures routinely conveyed both an unmistakable authority and a seductive intimacy—often in the very same frame.

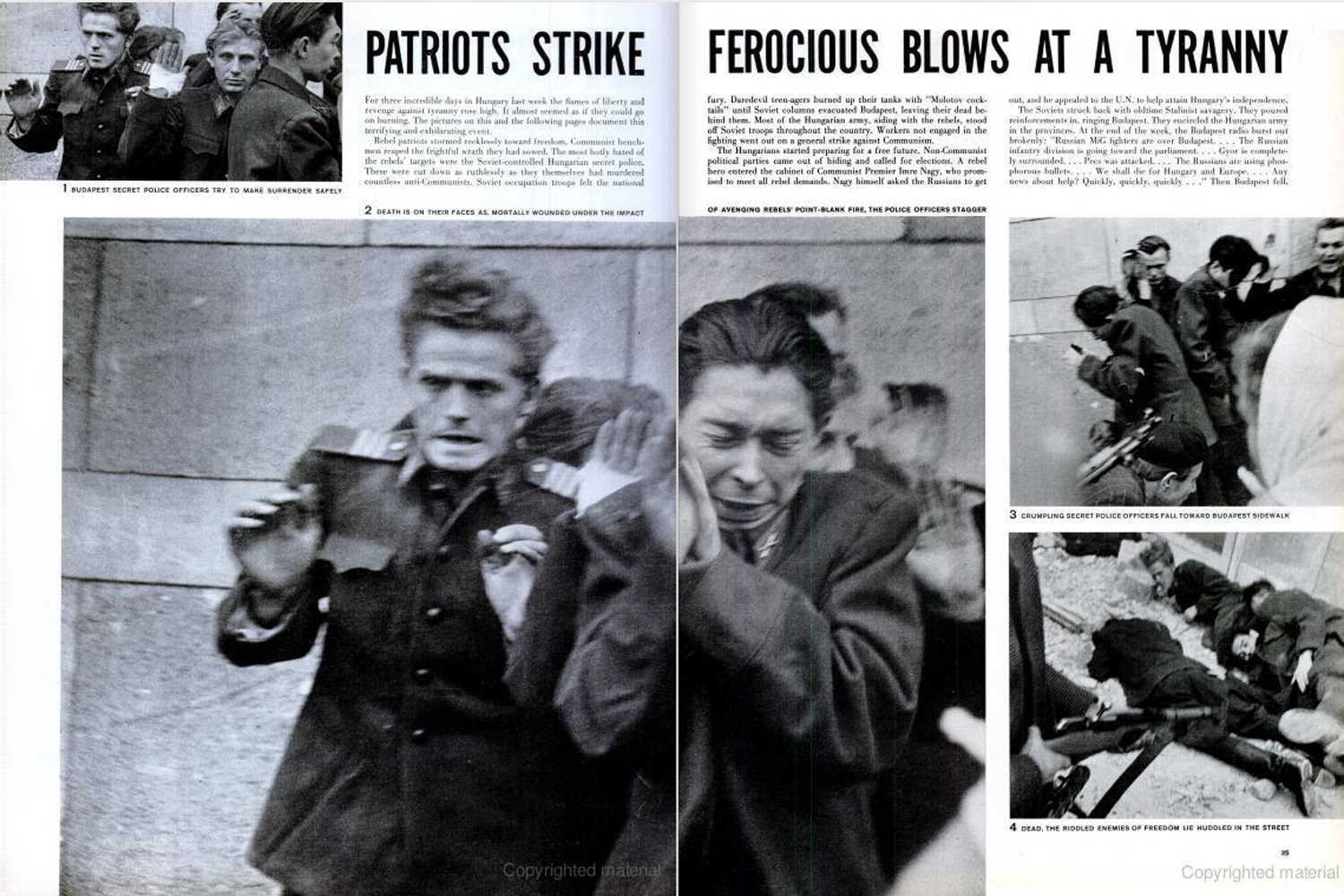

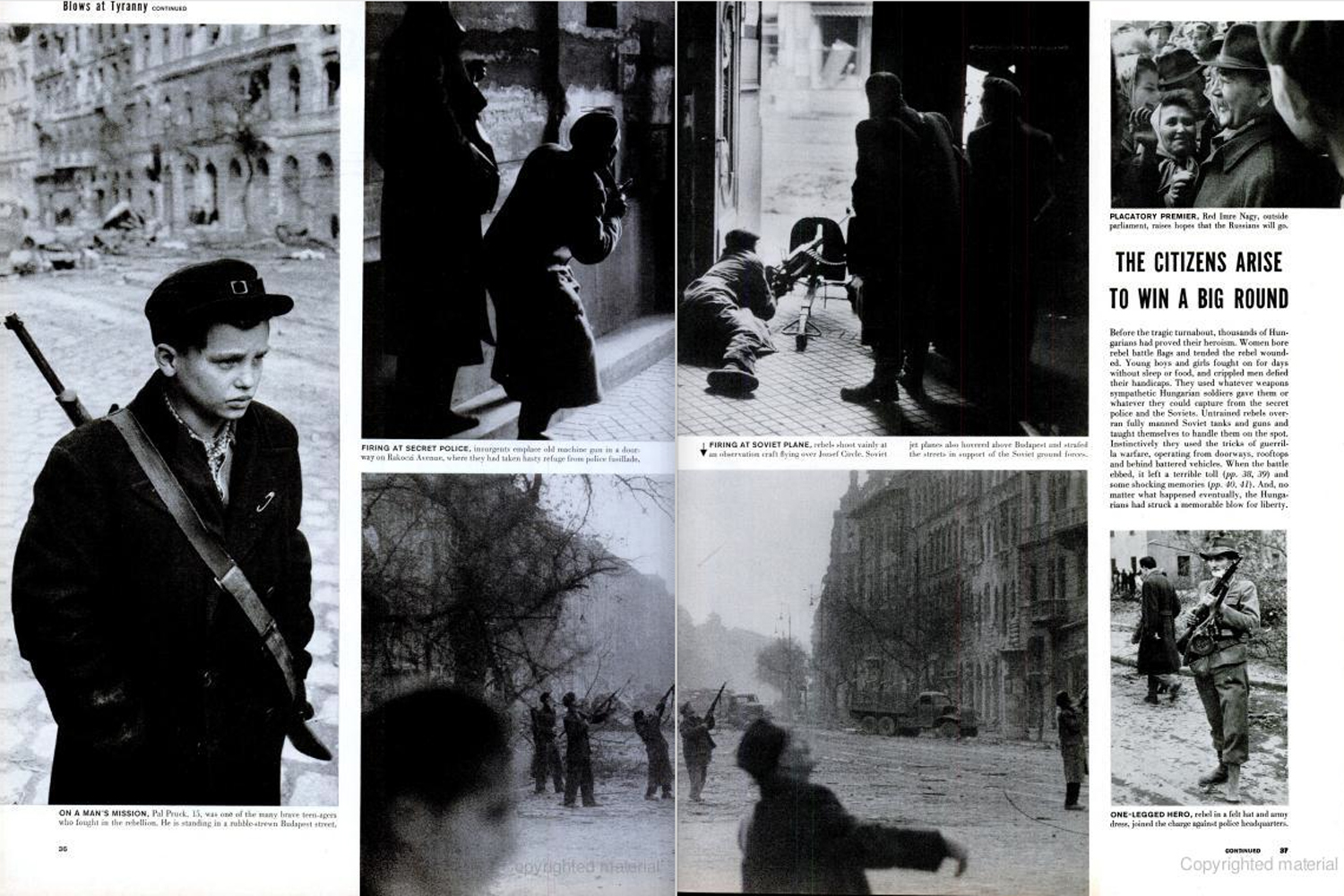

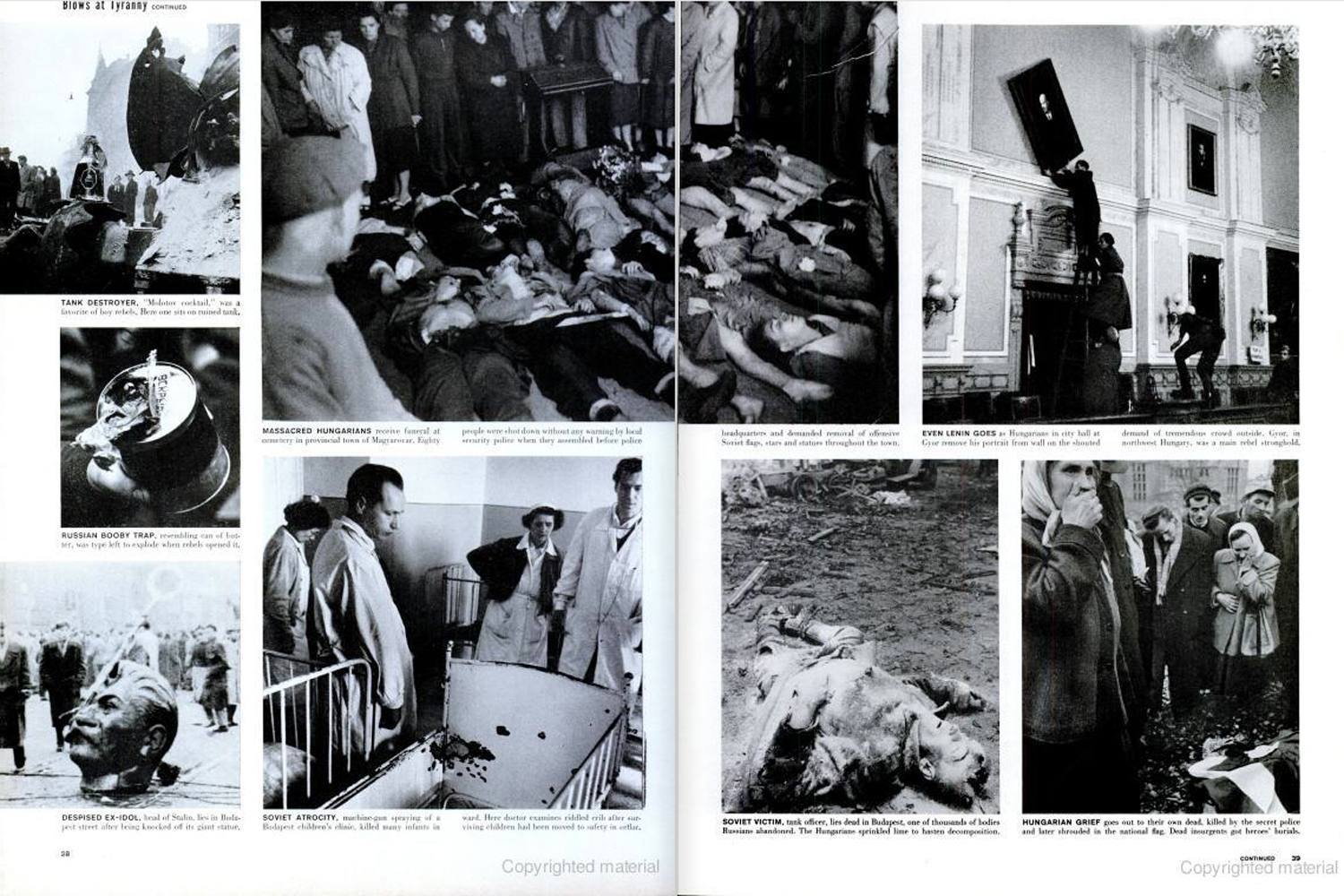

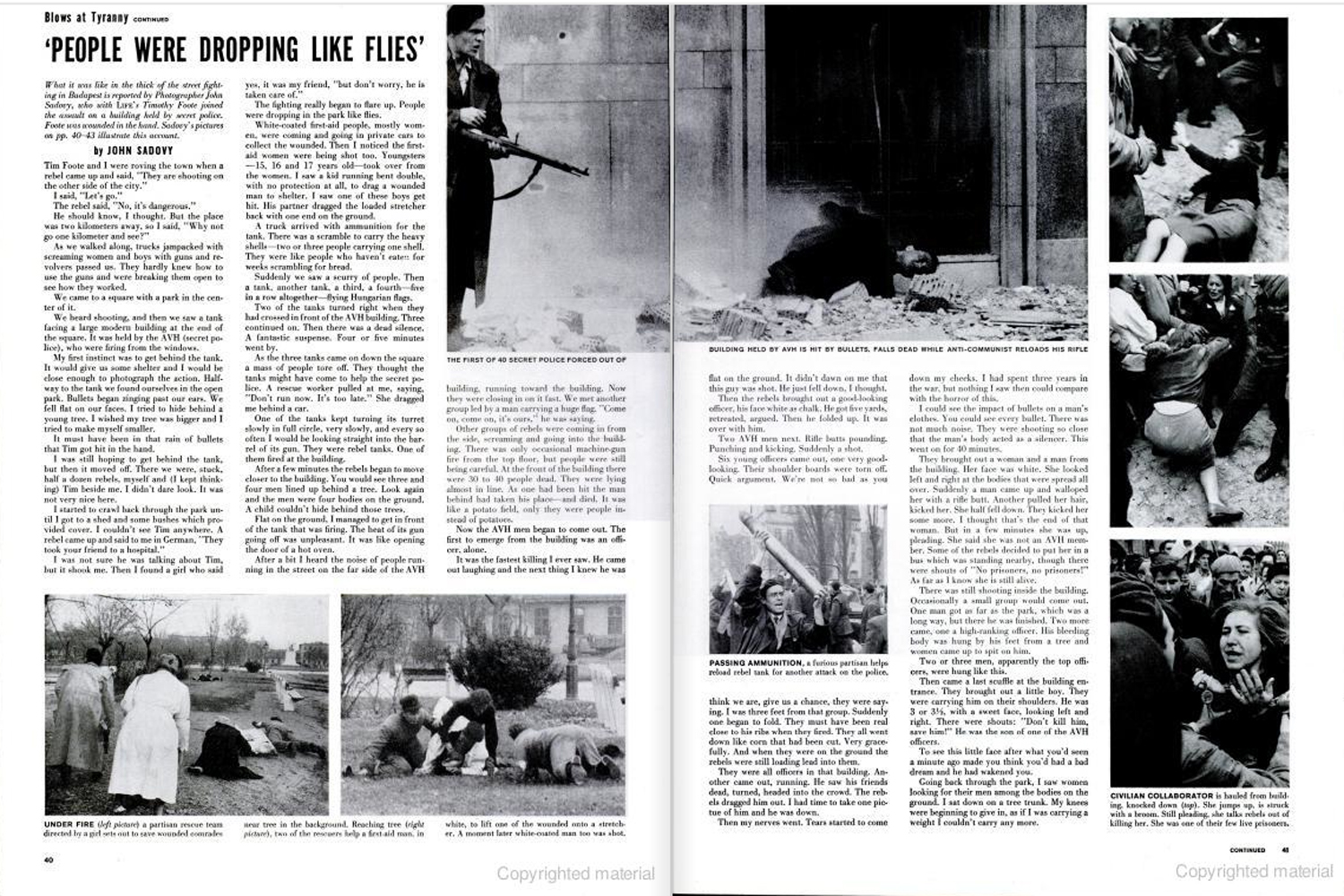

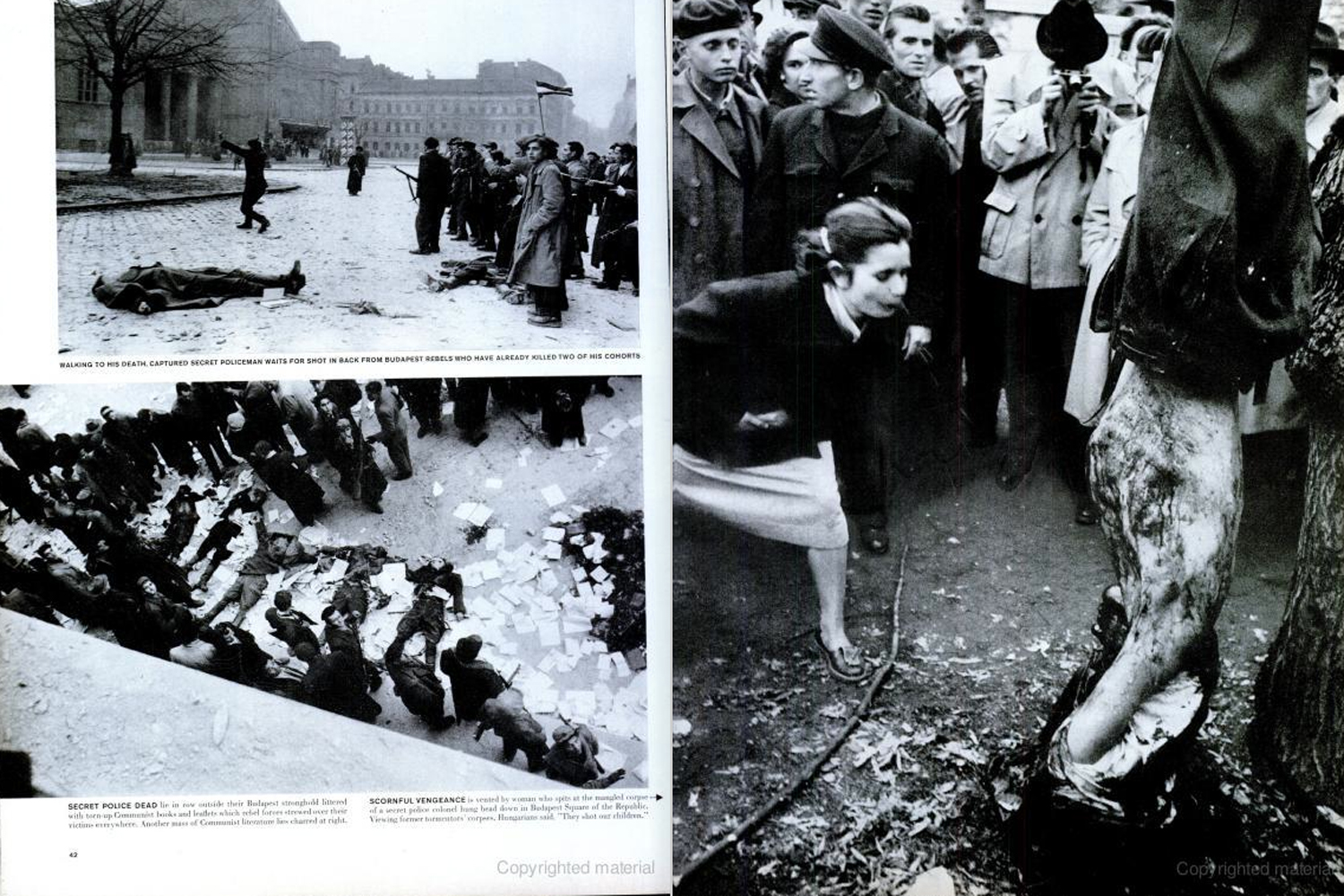

In its Nov. 12, 1956, issue, meanwhile, in an article titled, “Patriots Strike Ferocious Blows at a Tyranny,” LIFE magazine commemorated the short-lived uprising like this:

For three incredible days in Hungary last week the flames of liberty and revenge against tyranny rose high. It almost seemed as if they could go on burning. The pictures on this and the following pages document this terrifying and exhilarating event.

Rebel patriots stormed recklessly toward freedom, Communist henchmen reaped the frightful wrath they had sowed. The most hotly hated of the rebels’ targets were the Soviet-controlled Hungarian secret police. These were cut down as ruthlessly as they themselves had murdered countless anti-communists. Soviet occupation troops felt the national fury. Daredevil teenagers burned up their tanks with “Molotov cocktails” until Soviet columns evacuated Budapest, leaving their dead behind them. Most of the Hungarian army, siding with the rebels, stood off Soviet troops throughout the country. Workers not engaged in the fighting went out on a general strike against Communism.

The Soviets struck back with old-time Stalinist savagery. They poured reinforcements in, ringing Budapest. They encircled the Hungarian army in the provinces. At the end of the week, the Budapest radio burst out brokenly: “Russian MiG fighters are over Budapest. . . . The Russian infantry division is going toward the parliament. . . . Gyor is completely surrounded. . . . Pecs was attacked. . . . The Russians are using phosphorous bullets. . . . We shall die for Hungary and Europe. . . . Any news about help? Quickly, quickly, quickly . . .” Then Budapest fell.

A month after Soviet troops had retaken the capital and the rest of the country, LIFE published another major article on the insurrection—this time singling out the fearlessness of Hungary’s women for praise:

In Budapest last week . . . the Russian masters and their desperate Hungarian puppets faced a new and formidable foe. The city’s women, some of whom had fought earlier at the side of their men and then had bitterly buried the men who had fallen, suddenly banded together in a series of fresh demonstrations of defiance.

“Only women are wanted this time,” they shouted as they joined up in the streets. Then, ignoring the ominous presence of security police and Russian tanks, they marched with flowers and flags to a service commemorating their dead. The men doffed their hats in tribute as the women paraded past and joined with them in the stirring words of a forbidden song—“We shall never be slaves.”

Thirty-three years to the day after the start of the uprising, on Oct. 23, 1989, president Mátyás Szűrös officially declared the establishment of the Hungarian Republic, replacing in an instant the Hungarian People’s Republic. A few weeks later, on Nov. 9, 1989, thousands of people attacked a brute, concrete symbol of the Cold War—and of the Warsaw Pact’s illegitimacy—not with rifles and Molotov cocktails, but with sledgehammers and pickaxes. Four decades after the Hungarian Revolution had ended in defeat, the Berlin Wall—which had not yet been built when Budapest first rose up against the USSR—peacefully fell.

The Cold War was over.

Ben Cosgrove is the Editor of LIFE

More Must-Reads from TIME

- Why Trump’s Message Worked on Latino Men

- What Trump’s Win Could Mean for Housing

- The 100 Must-Read Books of 2024

- Sleep Doctors Share the 1 Tip That’s Changed Their Lives

- Column: Let’s Bring Back Romance

- What It’s Like to Have Long COVID As a Kid

- FX’s Say Nothing Is the Must-Watch Political Thriller of 2024

- Merle Bombardieri Is Helping People Make the Baby Decision

Contact us at letters@time.com