Some magazine stories are bigger than others. Bigger in scope, intent, audacity. And then there are those stories that are bigger in retrospect — stories that gain in stature and influence as the years pass and are cited as groundbreaking because of what they signified when they first appeared. Few stories of the latter variety can compare with the very first cover story LIFE magazine ever ran: photographer Margaret Bourke-White’s magnificent feature on the construction of Montana’s Fort Peck Dam.

After all, as a statement by a new magazine about the lengths to which it’s willing to go to bring the world, in all its thrilling complexity, into homes all over America, Bourke-White’s picture story could hardly be bettered. Somehow grand and intimate at once, her photographs — and the prominence with which LIFE displayed them — made it plain that here was a magazine unafraid to tackle genuinely big stories in new and imaginative ways.

[Buy the book, 75 Years: The Very Best of LIFE]

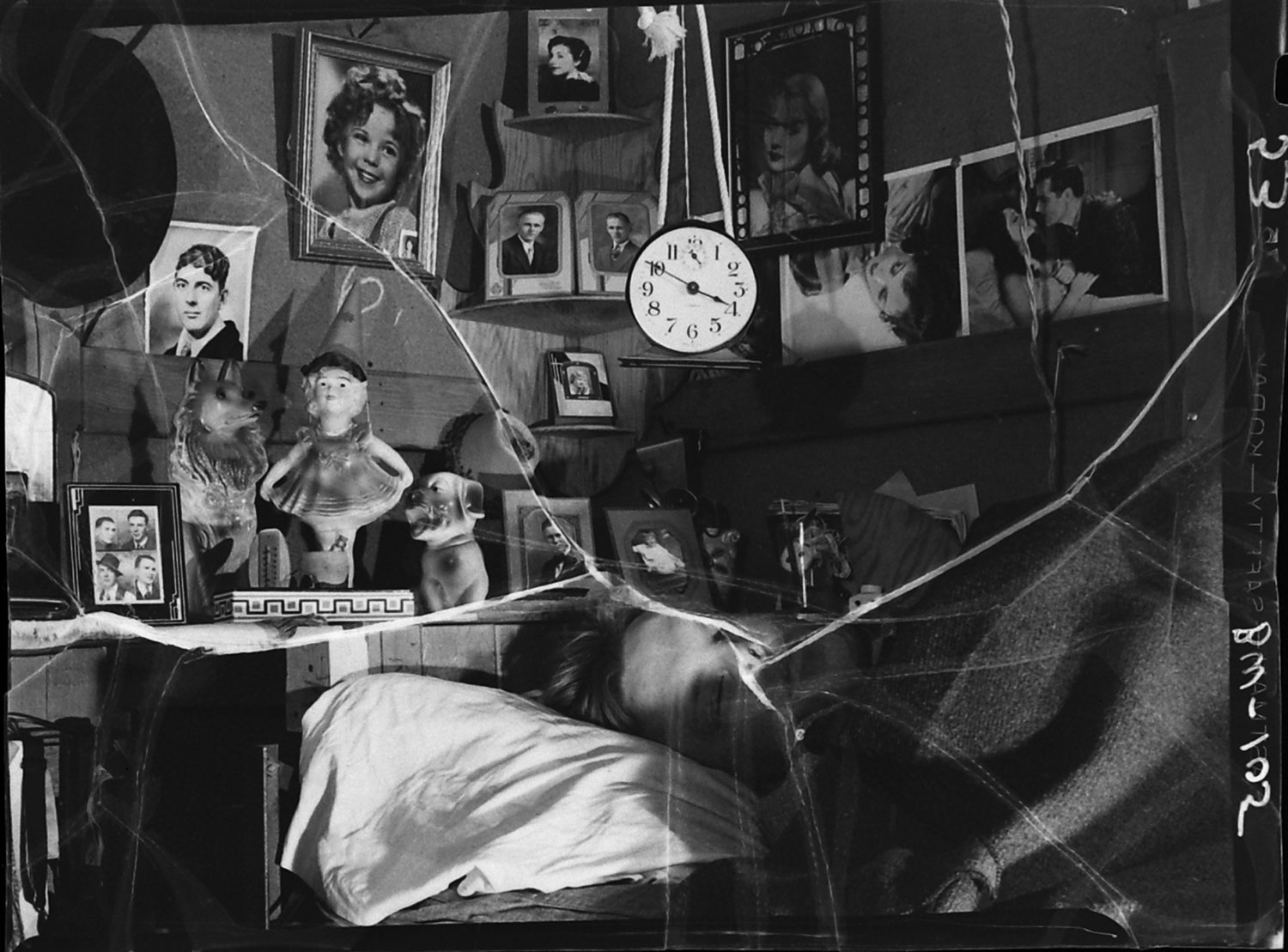

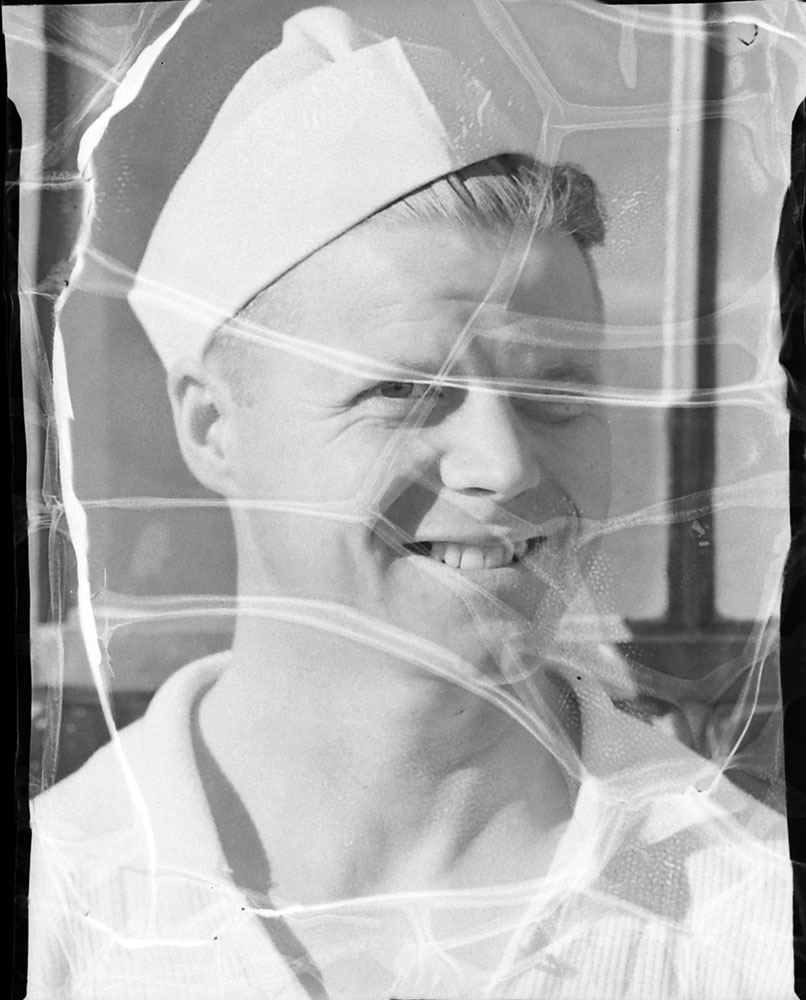

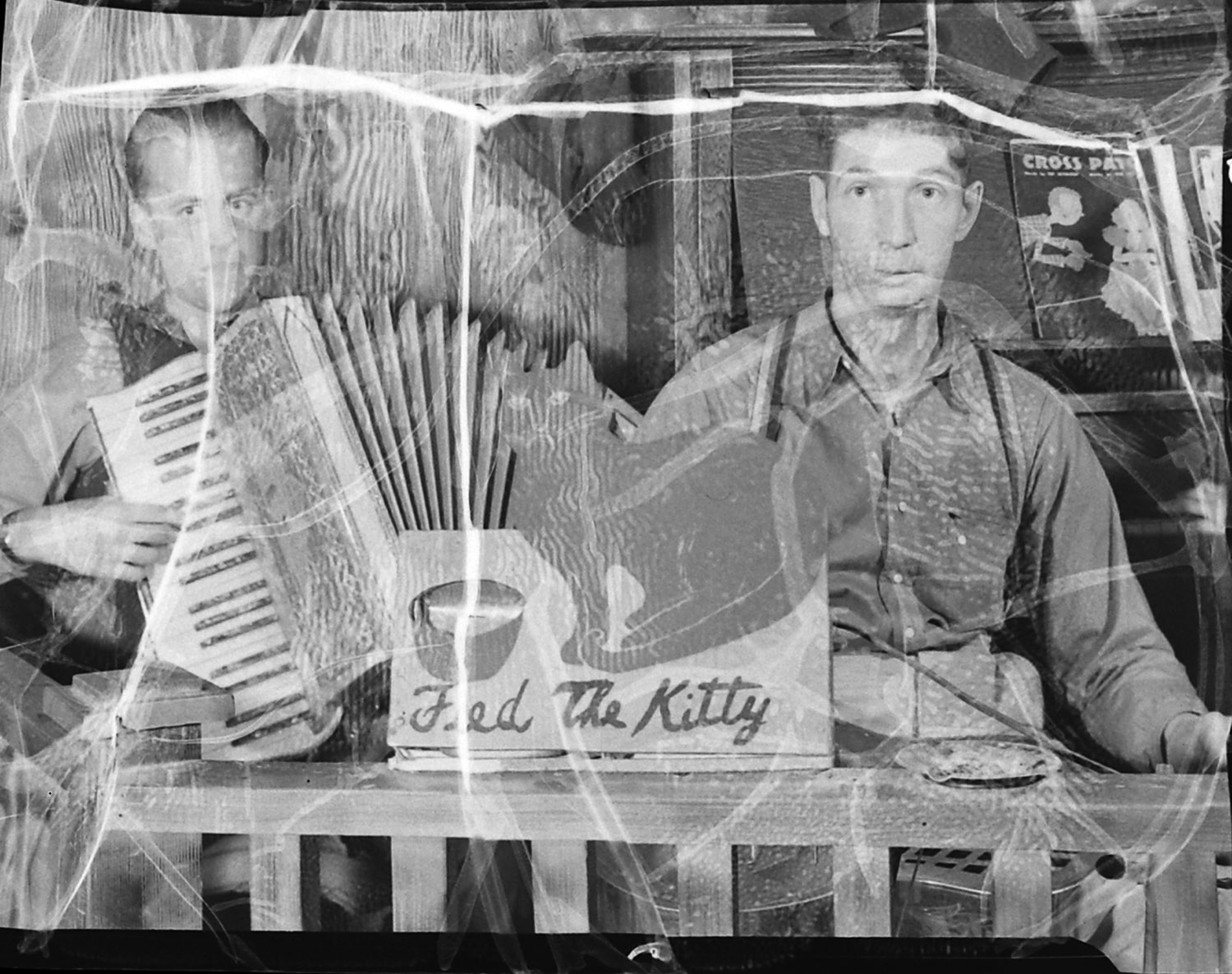

All of which makes the subsequent treatment of the most essential elements of that historic assignment — Bourke-White’s negatives — so puzzling and, in a way, dismaying. As astonishing as it might sound, a good number of the Fort Peck negatives have been so badly damaged, or have been allowed to deteriorate to such a degree over the years, that they are, for all intents and purposes, no longer viable. Prints can not be made from them. The images themselves have degraded to the point where key details have been forever lost.

They are, in short, ruined.

The mystery of how these negatives came to be so damaged is heightened, in a way, by the fact that, after more than 75 years, so many of the Fort Peck negatives remain in pristine condition. Were some negatives lent out, accidentally damaged by an unknown hand, and returned? Were these particular negatives placed on some random heat source, like a radiator, and forgotten? Was there a chemical spill that affected some, but not all, of the negatives? Were they damaged while being developed?

[See the Fort Peck Dam cover story on LIFE.com]

Whatever the circumstances under which these essential, seminal negatives were corrupted, the resulting visuals, as this gallery illustrates, offer an eloquent (if wholly unintentional) commentary on the disruption, decay and loss inherent in all analog photography — and, in a broader sense, in the physical world as a whole.

But beyond all of the technical and even existential questions that Bourke-White’s damaged negatives raise, it’s also worth noting, and celebrating, one other characteristic that makes these artifacts so fascinating: namely, that they just look really, really cool.

More Must-Reads from TIME

- Donald Trump Is TIME's 2024 Person of the Year

- Why We Chose Trump as Person of the Year

- Is Intermittent Fasting Good or Bad for You?

- The 100 Must-Read Books of 2024

- The 20 Best Christmas TV Episodes

- Column: If Optimism Feels Ridiculous Now, Try Hope

- The Future of Climate Action Is Trade Policy

- Merle Bombardieri Is Helping People Make the Baby Decision

Contact us at letters@time.com