![Eisenhower makes V with surrender pens, German and U.S. pen at right, Russian at left. With 'Ike': [Chief of Staff Lieut. General Bedell] Smith, Secretary Kay Summersby, [RAF's Arthur] Tedder.](https://api.time.com/wp-content/uploads/2013/05/16_00637534.jpg?quality=85&w=2400)

On a rainy Saturday night in early May, 1945, LIFE photographer Ralph Morse was working in his hotel room in Paris, writing captions for a series of photos he’d made a few days earlier, when a U.S. Army press information officer knocked on his door. “Grab your cameras,” the PIO said. “Let’s go.”

“I have to finish up these captions,” Morse protested.

“This is more important,” the press officer said. Something in his manner told Morse that “important” might be an understatement. Dressed in his correspondents’ uniform, Morse grabbed his cameras and his raincoat and went down to the street in front of the hotel.

“There was a big black Cadillac there, and four or five Jeeps,” Morse recently told LIFE.com, recalling that long-ago night. “I’d be damned if I was going to let my cameras get soaked, so I jumped into the Caddy. We started off, and right away we all knew we were headed for Reims. You could feel it.”

Reims was where SHAEF — the Supreme Headquarters of the Allied Expeditionary Force — was located for the last two years of the Second World War. Roughly 90 miles northeast of Paris, the town of Reims — and, specifically, the “little red schoolhouse” where Supreme Allied Commander Gen. Dwight Eisenhower and his staff were headquartered — was about to enter history as the exact spot where the war in Europe would come to an end. The long-rumored German surrender, coming hard on the heels of several leading Nazi figures’ suicides, including Hitler himself, was finally at hand. And Ralph Morse, who had covered so much of the war, from Guadalcanal to the liberation of Paris in the summer of 1944, would have a front row seat.

But not quite yet.

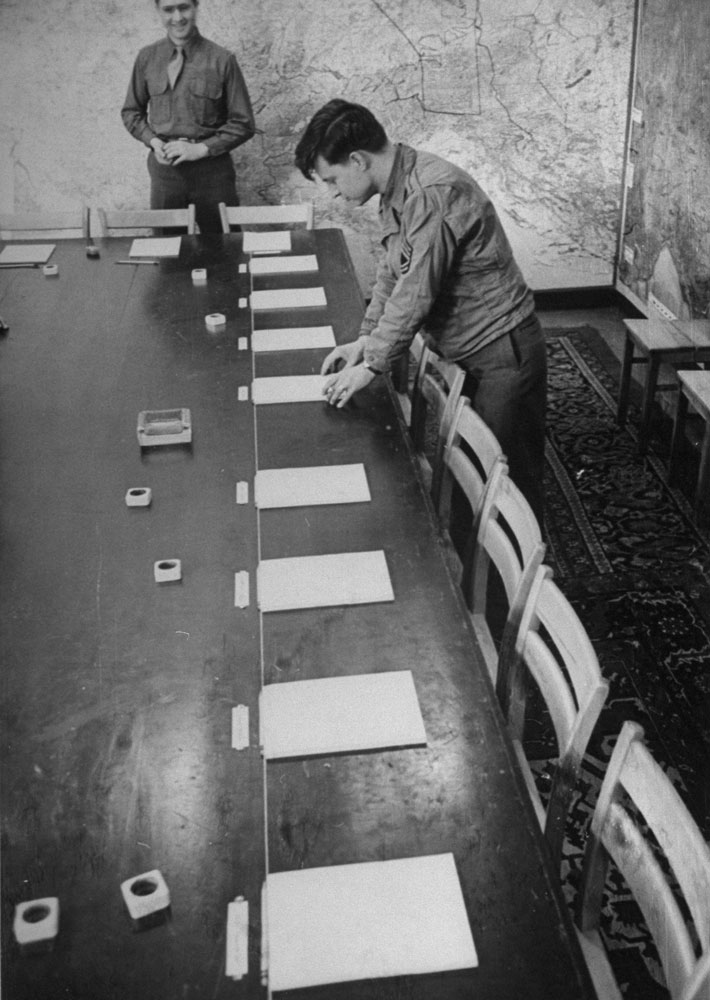

“We got to the little red schoolhouse,” Morse said, “and learned that the Germans were coming to sign the surrender documents — in about ten minutes. We all started scrambling around, trying to get ourselves set up for the ceremony. But then it turned out there was some sort of mix-up, the Germans couldn’t sign that night after all, and the other correspondents and I were left there, waiting.

“I wasn’t going to leave that place until the Germans came back and signed,” Morse remembered. “I was terrified I’d step out for an hour, and miss the surrender! So I stayed there at headquarters for two solid days — I slept on the the floor, on my raincoat, and ate hamburgers for every meal — and I was still there when the German delegation, led by [Generaloberst Alfred] Jodl, finally arrived to sign the ‘instrument of surrender,’ as it was called, a few hours before dawn on May 7.”

![The Germans, Major [Wilhelm] Oxenius, Col. General [Alfred] Jodl, Admiral General [Hans-Georg] von Friedeberg march stiffly in under floodlights at 2:39 a.m. Monday, May 7. Von Friedeberg was coolest of three.](https://api.time.com/wp-content/uploads/2013/05/07_00637496.jpg?quality=75&w=2400)

![Jodl, wearing Iron Cross low on his left breast, is seated between the major and admiral. With [German Head of State Karl] Donitz's authorization, he has nothing to do but sign the surrender.](https://api.time.com/wp-content/uploads/2013/05/08_00637504.jpg?quality=75&w=2400)

![For Red high command, Major General Ivan Susloparov signs, to be followed by French General Francois Sevez for [Alphonse] Juin, commander of French expeditionary forces. At right, [American Gen. Carl Andrew] Spaatz.](https://api.time.com/wp-content/uploads/2013/05/12_00637499.jpg?quality=75&w=2400)

![Eisenhower makes V with surrender pens, German and U.S. pen at right, Russian at left. With 'Ike': [Chief of Staff Lieut. General Bedell] Smith, Secretary Kay Summersby, [RAF's Arthur] Tedder.](https://api.time.com/wp-content/uploads/2013/05/16_00637534.jpg?quality=75&w=2400)

More Must-Reads from TIME

- Donald Trump Is TIME's 2024 Person of the Year

- Why We Chose Trump as Person of the Year

- Is Intermittent Fasting Good or Bad for You?

- The 100 Must-Read Books of 2024

- The 20 Best Christmas TV Episodes

- Column: If Optimism Feels Ridiculous Now, Try Hope

- The Future of Climate Action Is Trade Policy

- Merle Bombardieri Is Helping People Make the Baby Decision

Contact us at letters@time.com