The Witcher 3: Wild Hunt arrives Tuesday, like a meteor heralding an extinction level event masquerading as a gritty Slavic myth-o-rama. The doomed: all sandbox fantasy roleplaying games prior, forced to measure up and found wanting.

Polish developer CD Projekt Red’s tale of a cat-eyed, glam-haired, drug-elevated monster slayer, once as obscure as Bethesda’s hence primetime-friendly The Elder Scrolls series, now separates money from pockets with ease. Preorders for The Witcher 3: Wild Hunt are past one million, the studio reported last week. That’s more than half as many total copies sold of 2011’s The Witcher 2: Assassins of Kings, itself both a critical and commercial triumph.

The Witcher 3: Wild Hunt thus looks poised to shatter its predecessor’s numbers, buttressed this time by PC, PlayStation 4 and Xbox One versions launching simultaneously (The Witcher 2: Assassins of Kings was for PC and Xbox 360 only).

So what is The Witcher 3: Wild Hunt? Only the biggest open-world roleplaying game of the year, one of the most critically acclaimed in years, and the final act of a trilogy that since the first act arrived in October 2007, has been as keen to upend morally simplistic, male-angled fantasy tropes as that other epic fiction franchise everyone raves about.

If you’re newcomer-curious, here’s a quick review of why people love The Witcher so much.

It’s based on sophisticated fantasy writing

Thank Polish writer Andrzej Sapkowski for the Witcher-verse and its guttural, morally ambivalent, antihero. Sapkowski, whose first books appeared in the early 1990s and weren’t translated into English until the late 2000s, placed his protagonist Geralt of Rivia in a mimetic fantasy world with enough socio-economic nuance to ground a political science dissertation. Here be racism, sexism, classism, economic inequality and injustice, wrapped in a bleak, often cynical worldview informed by a nation with a history of repeated occupation and counter-occupation by larger, historically thuggish rival powers.

Your mileage will definitely vary

The original game offered three possible endings, and not just superficial codas where one or the other cutscene plays before the credits roll. Pivotal decisions in The Witcher could upend the narrative course, determining who lived and died, and dictating who might ally with or turn against you when crucial battles arrived.

The Witcher 2: Assassins of Kings, though still restricting players to progressive level-like areas, further developed that organic storytelling formula, boasting 16 possible endings with so much interactive nuance to its narrative pathing that multiple play-throughs could feel like completely different games.

The Witcher 3: Wild Hunt, which shifts the series to freeform exploration, expands its possible outcome tally to a whopping 36, and the developers claim those windups are born of organic pivot points along the way that add up to hundreds of narrative permutations (that, in a game where a single pass takes upwards of 50 hours).

The fights are way better than most

All roleplaying games are really elaborate fighting games, so the clicky-tappy things you wind up doing over and over–in some cases for hundreds of hours–has to be both novel and progressive. Studio CD Projekt Red’s approach has been both in each of The Witcher games, progressing from a clever rhythm-focused keyboard/mouse model in the original, to deep toolboxes of offensive and defensive maneuvers augmented by secondary tricks and talent trees that unlock ever more nuanced abilities.

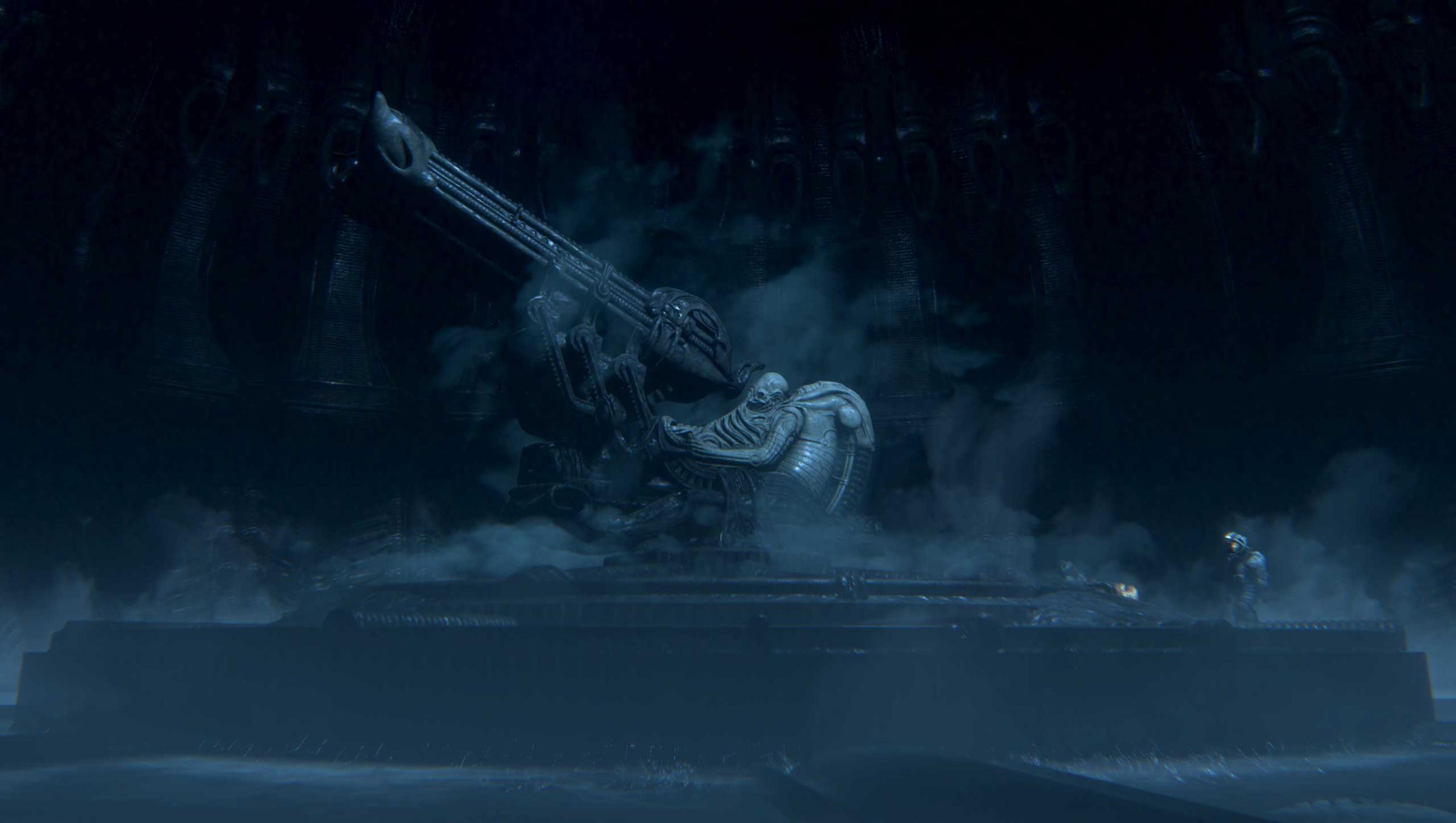

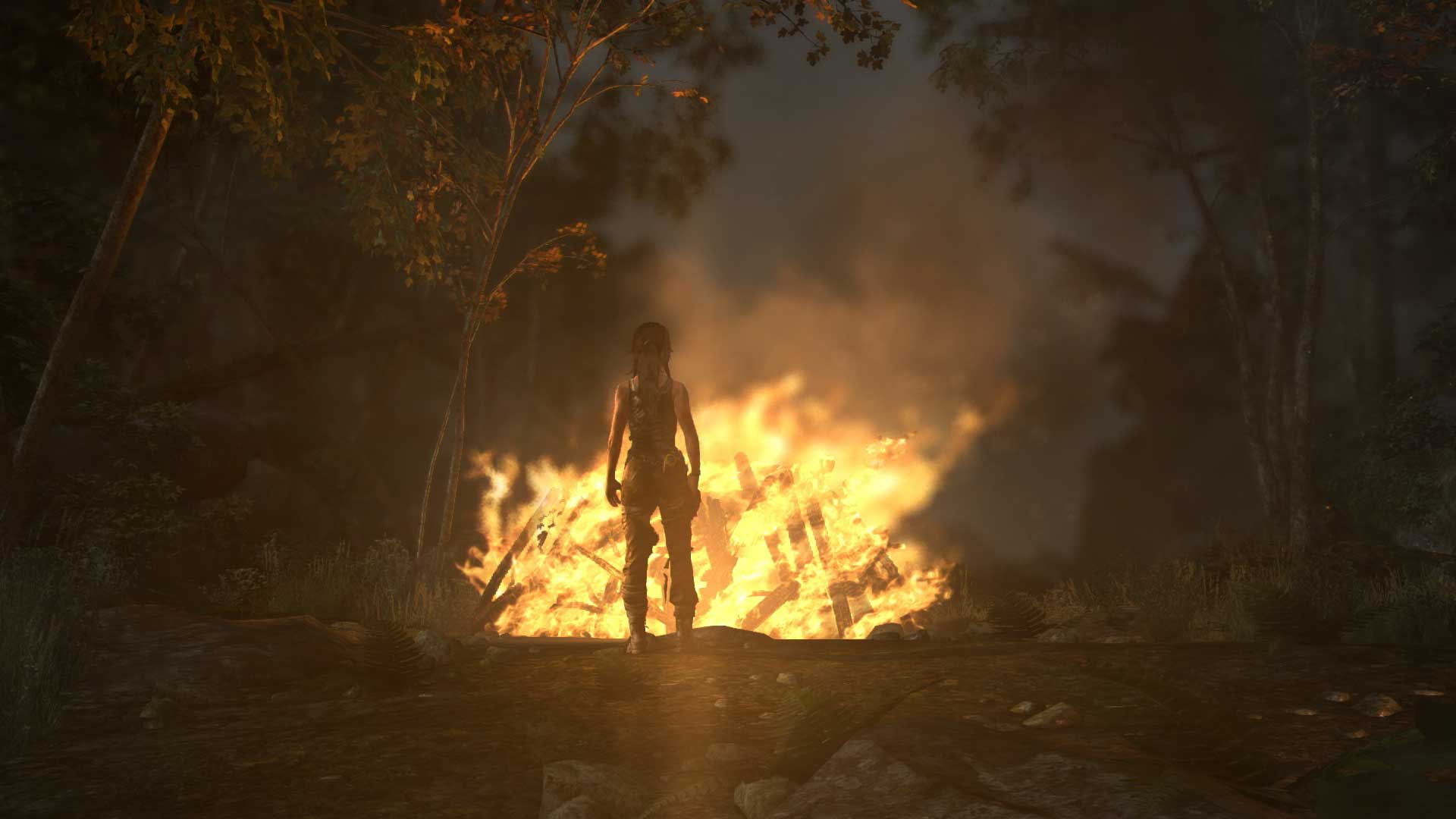

The world looks and feels like nothing else in fantasy gaming

Square Enix’s Final Fantasy games are more graphically inventive (they’re certainly more gonzo!), sure, but in a crowded field that’s been tediously riffing on Tolkien for decades, The Witcher games feel like idiosyncratic curios. Inspired by Slavic mythology, its bosky dells, ruin-flanked hills and patchwork fields sound paradoxically elegiac notes, juxtaposing heart-stopping sunsets filtered through wind-whipped trees with war-wracked, blood blackened fields of corpses, sometimes piled like cordwood. And instead of squaring off with trolls, orcs, goblins, dragons and multicolored blobs of dungeon-delving goo, you’re up against folkish, far weirder-sounding Eastern European creatures like striga, necrophages, bruxa and vodyanoi, as well as warped takes on traditional fiends, e.g. noonwraiths, alghouls and dagon worshippers.

But the most marvelous monsters in the game aren’t mythic at all

As I put it when reviewing the original game eight years ago: “For all the wonderfully ‘un-Tolkien-y’ alghouls and echinops and graveirs and bloedzuigers you’ll grapple with, the most hideous monsters in the game aren’t the ones with six or a dozen consonants crowding a single vowel, but other humans, like you.”

See The 15 Best Video Game Graphics of 2014

More Must-Reads from TIME

- Why Trump’s Message Worked on Latino Men

- What Trump’s Win Could Mean for Housing

- The 100 Must-Read Books of 2024

- Sleep Doctors Share the 1 Tip That’s Changed Their Lives

- Column: Let’s Bring Back Romance

- What It’s Like to Have Long COVID As a Kid

- FX’s Say Nothing Is the Must-Watch Political Thriller of 2024

- Merle Bombardieri Is Helping People Make the Baby Decision

Write to Matt Peckham at matt.peckham@time.com