Welcome to the NFL, Jeb Bush. It’s nasty out there on the presidential campaign trail, isn’t it? You shake hands you really don’t want to shake, make speeches you really don’t want to make, and get asked all kinds of questions you really don’t want to answer. And if you’re feeling especially picked on, well, you’re right.

That, like it or not, is part of a contest you’ve been involved in a whole lot longer than you’ve been a sort-of, kind-of, not-quite-announced presidential candidate. It’s the siblings war, and as with any other person with a brother or sister who ever ratted you out to mom or clobbered you in the playroom, it’s a battle you’ve been fighting for as long as you can remember.

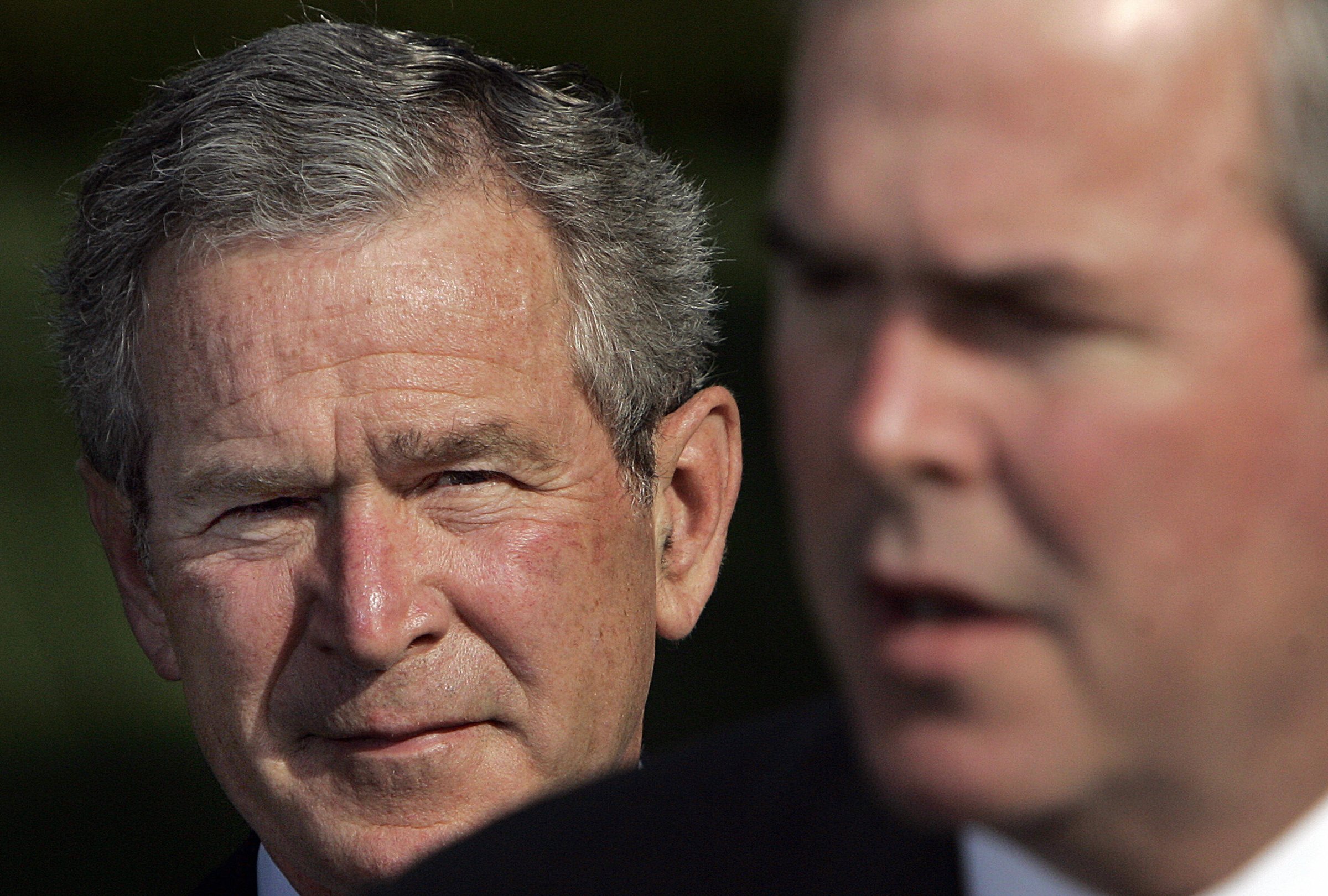

The problem you’re facing at the moment—as every news outlet in the country has delighted in reminding you—concerns the Iraq war, which started and unraveled on your big brother George W.’s watch. Last Saturday, you taped a segment for Fox News—hardly an unfriendly outlet for a Republican—and Megan Kelly asked you if, knowing what you know now, you’d have authorized the 2003 invasion. You answered with three words I bet you’d really like not to have said: “I would have.”

Never mind that you later backtracked, saying you’d misheard the question and thought Kelly was asking you what you’d have done if you’d only had the flawed intelligence that was available at the time. And never mind that the rest of your answer to Kelly seems to support that. “I would have,” you said in full, “and so would have Hillary Clinton, just to remind everybody. And so would have just about everybody that was confronted with the intelligence that they got.”

But that didn’t stop Politico from asking “Will Iraq take down another Bush?” That didn’t stop the New York Times from declaring, “Brother’s Past Proves Tricky for Jeb Bush.” And it won’t stop virtually every other sentient person on the planet from connecting you to George W.—for better and for worse.

That’s the way it is with sibs. Part of the problem is the glib association people outside the family make about brothers and sisters. Teachers, camp counselors, coaches, all assume that if your big sib was good in math or sports you will be too—and if you’re not, they’ll want to know why. And if the same big sib was a lousy student or a behavioral handful you have to overcome the assumption that you’ll be the same.

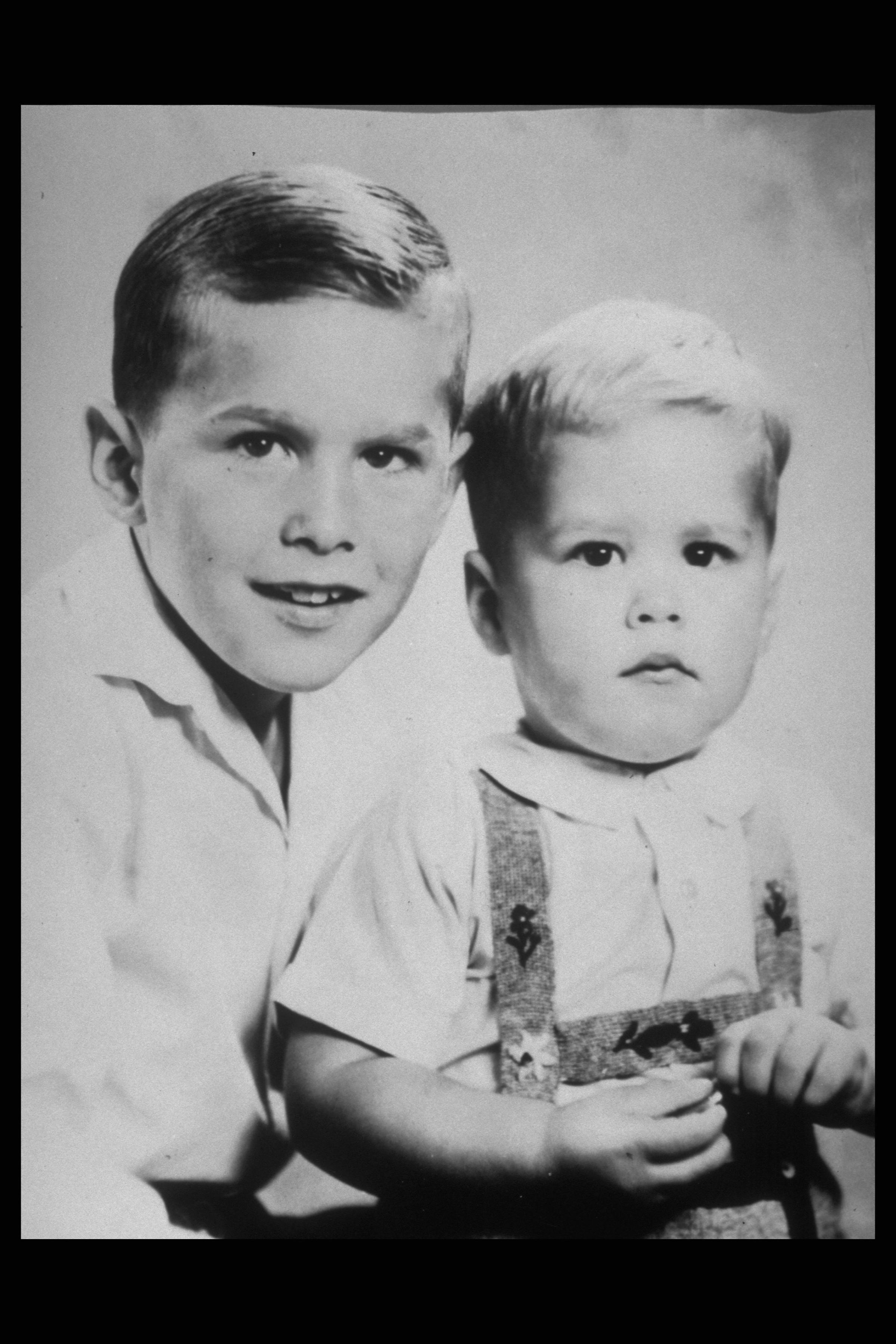

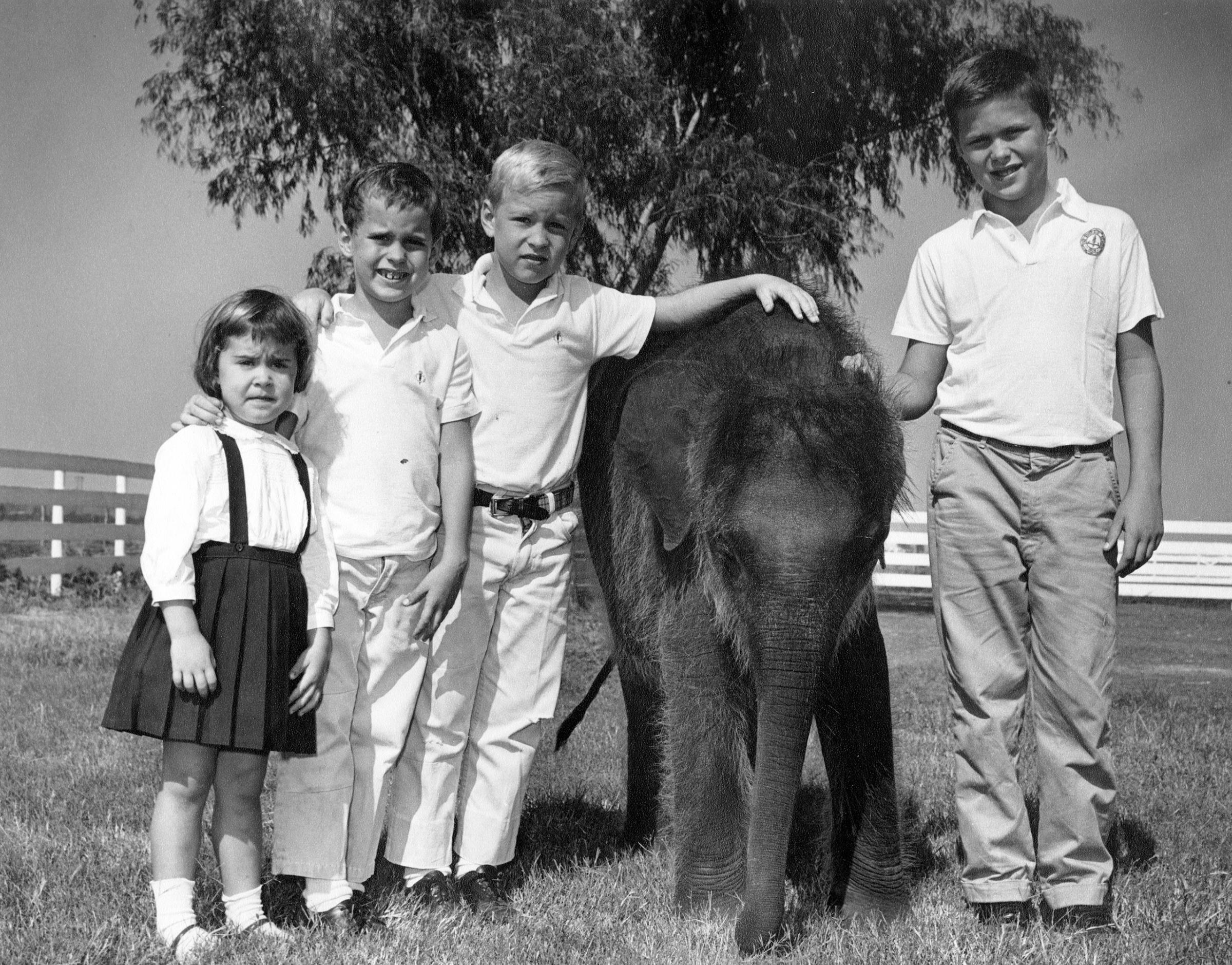

But a much bigger problem is the dynamic that unfolds within the sibling brood itself. Think of a family as a corporation. Mom and Dad are co-CEO’s and the kids are the products. George W. was the first one to come down the assembly line, and like any sole product in any start-up company, he was the exclusive focus of the bosses’ time, money, energy and attention. By the time you came along, those early resources had gone into the ledger as what the MBAs call sunk costs—investments that can never be gotten back. So if the company has to choose between Bush Son V.1 (that’s George) and Bush Son V.2 (that’s you), it’s usually not even close.

That’s at least part of the reason that even though George had the rep of the dilettante and layabout and you were thought of as The Serious One, he got the first shot at the presidential cookie jar and you’ve now got to work with the crumbs that are left. That’s at least part of the reason too that in 2013 even your Mom, who surely loves you like a son, was dismissive of your presidential prospects, telling Matt Lauer that you’re “by far the best-qualified man,” but that, “there are other people out there that are very qualified, and we’ve had enough Bushes.” That couldn’t have felt good.

You made the inevitable comparisons to your big brother much worse by going into the same line of work he and your father did. Family psychologists call this—straightforwardly enough—identifying. Your big brother or big sister gets all kinds of family attention for, say, starring in school plays, so you start going to auditions too. The problem is, the goodies start to get spread a little thin. No matter how many starring roles you land, you’ll still get only 50% of the parental applause for being the family’s performer. Better then to choose a different route—what the psychologists call de-identifying—play sports or join the chess club and get 100% of the laurels for those achievements.

But the most powerful—if least quantifiable—sibling dynamic you’re struggling with now is the business of love, loyalty and guilt. Take that nasty moment on May 13, when you were at a Reno, Nev. town hall and a 19-year-old college student said to you, “Your brother created ISIS.” Did you need that headache? No you did not.

You could have answered that charge by disavowing your brother—a simple, “Yeah, can you believe the mess he made?” would have done it. Certainly that’s the way any Democrat would go, as well as some Republicans trying to get a little distance from the serial messes of your brother’s two terms. But you can’t do that—not if you want to feel comfortable at the Kennebunkport Thanksgiving table next fall.

So you hedge and you elaborate and you decline to answer hypothetical questions—even if they’re fair and entirely predictable questions. And you sometimes get sick of it all and say, as you also did in Reno, “First and foremost, I am proud to be George W.’s brother. I can’t deny the fact that I love my family.”

No one doubts that that second statement is true. As for the first one? Well, only you know. But get used to the questions, get used to the problems, because they’re not going away. Presidencies are short; campaigns are even shorter. But the wonderful, awful, loving, vexing job of being a sib is forever.

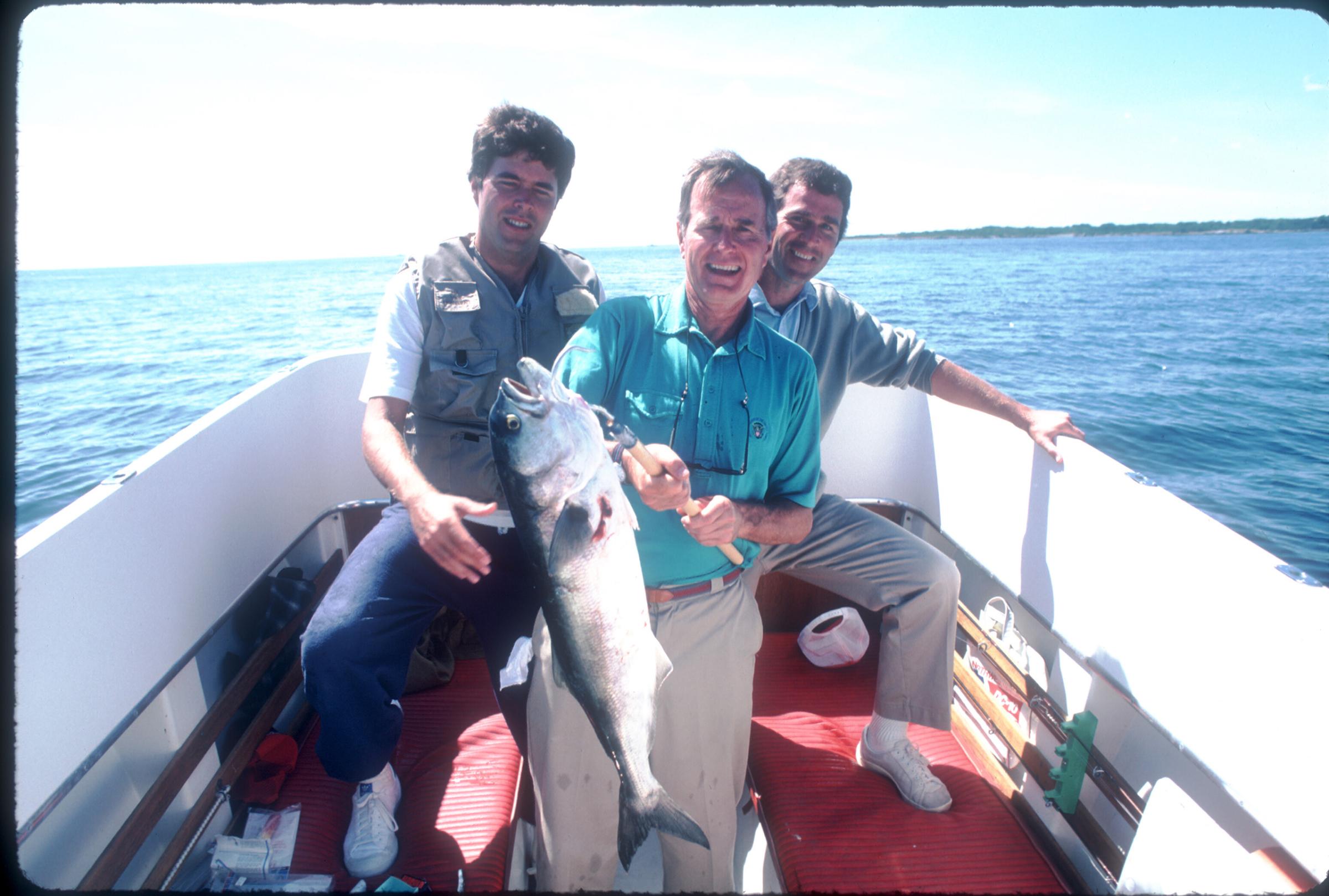

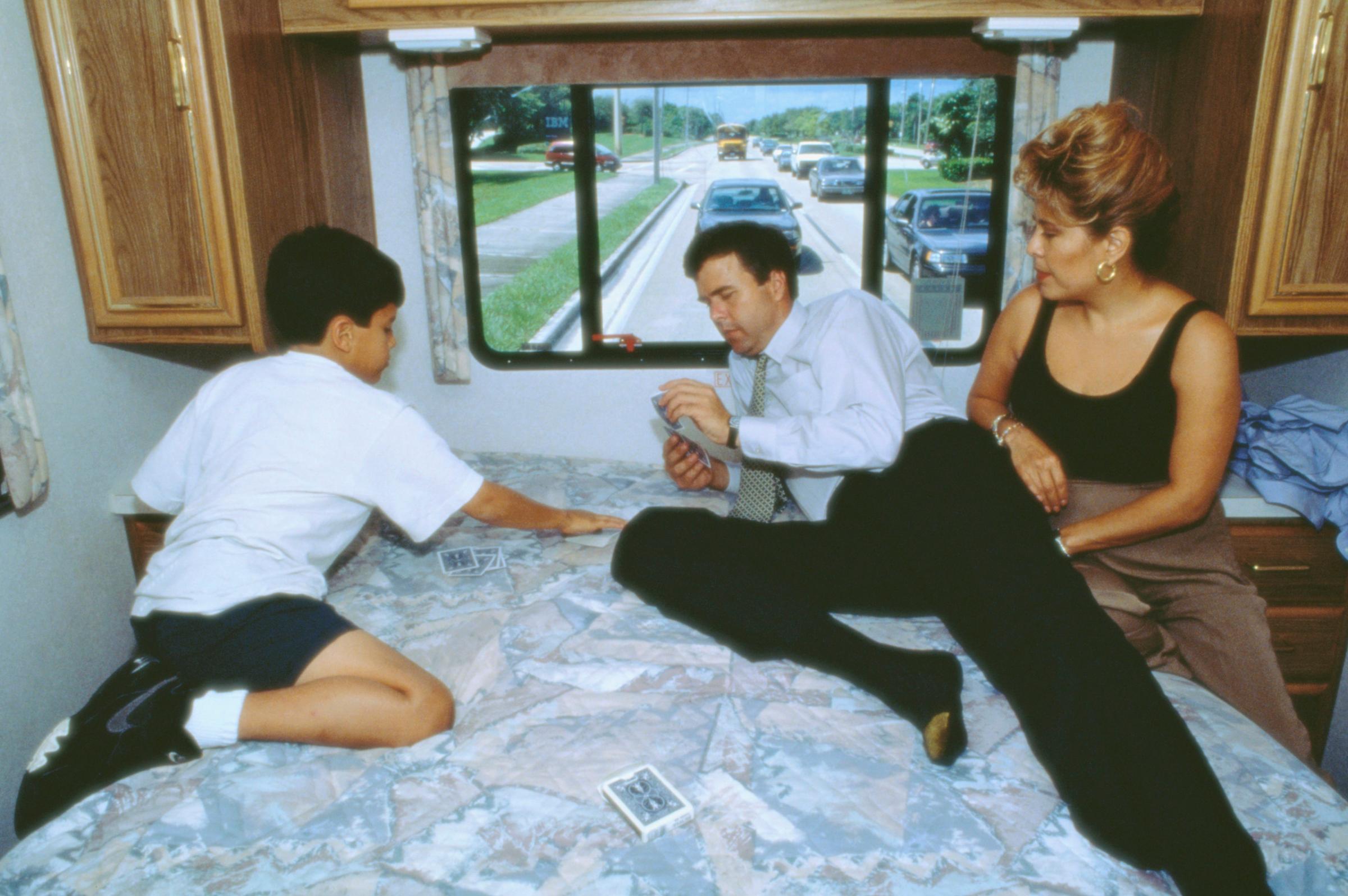

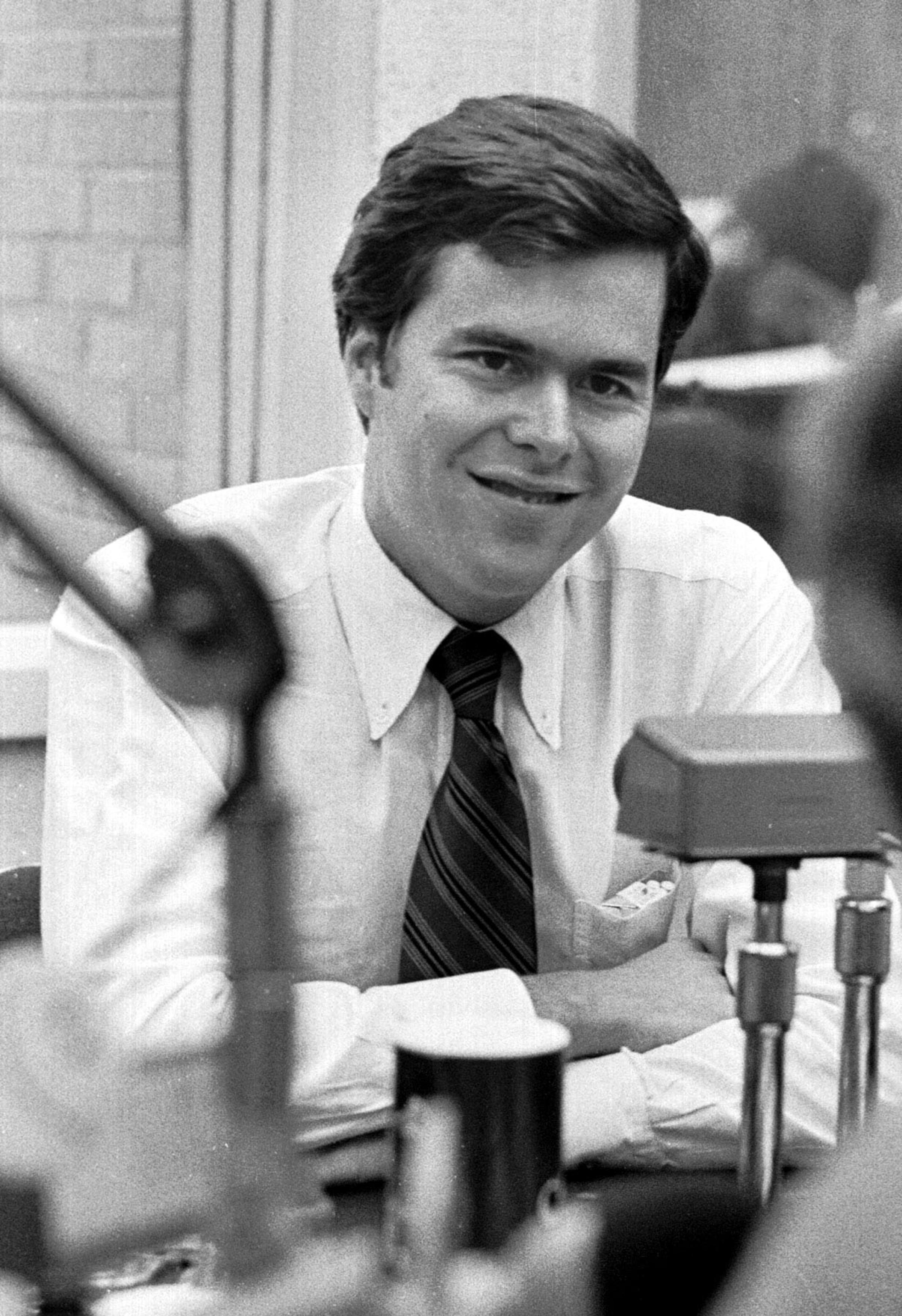

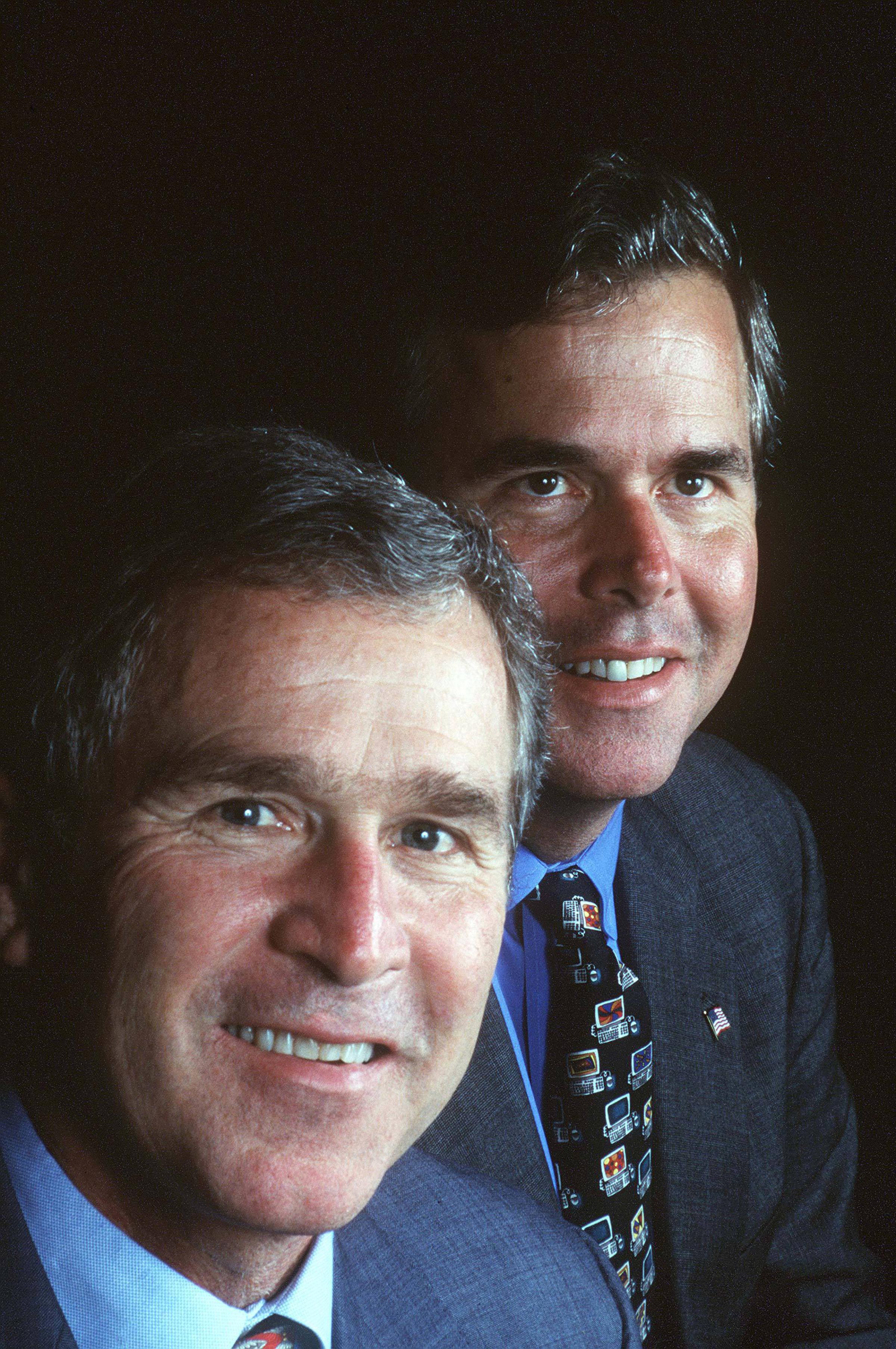

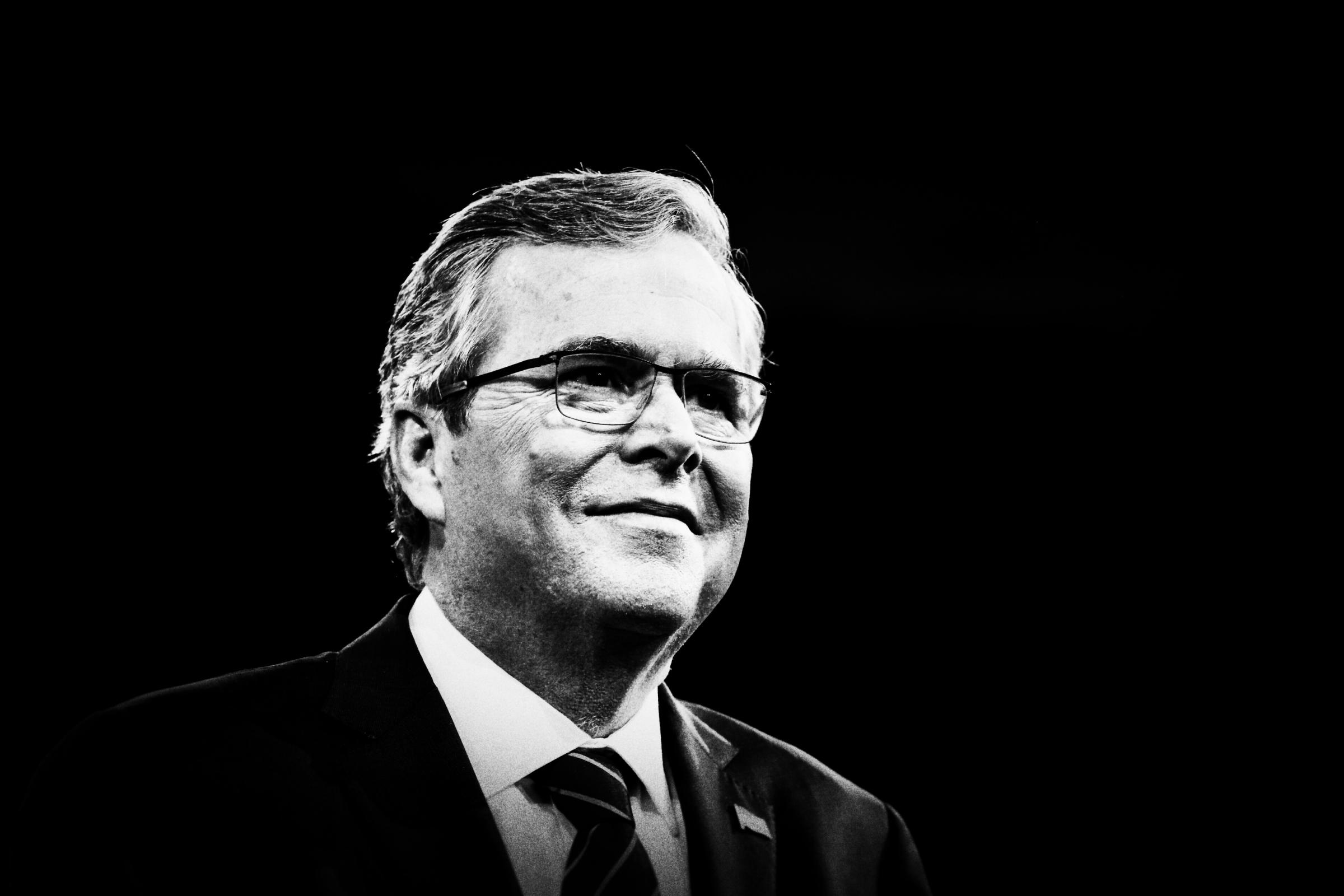

See Jeb Bush's Life in Photos

More Must-Reads from TIME

- Donald Trump Is TIME's 2024 Person of the Year

- Why We Chose Trump as Person of the Year

- Is Intermittent Fasting Good or Bad for You?

- The 100 Must-Read Books of 2024

- The 20 Best Christmas TV Episodes

- Column: If Optimism Feels Ridiculous Now, Try Hope

- The Future of Climate Action Is Trade Policy

- Merle Bombardieri Is Helping People Make the Baby Decision

Write to Jeffrey Kluger at jeffrey.kluger@time.com