Barcott is a journalist who has contributed to the New York Times, National Geographic and other publications. Scherer is TIME’s Washington bureau chief. Portions of this article were adapted from Barcott’s new book “Weed the People, the Future of Legal Marijuana in America,” from TIME Books, is now available wherever books are sold, including Amazon.com, Barnes & Noble and Indiebound.

Yasmin Hurd raises rats on the Upper East Side of Manhattan that will blow your mind.

Though they look normal, their lives are anything but, and not just because of the pricey real estate they call home on the 10th floor of a research building near Mount Sinai Hospital. For skeptics of the movement to legalize marijuana, the rodents are canaries in the drug-policy coal mine. For defenders of legalization, they are curiosities. But no one doubts that something is happening in the creatures’ trippy little brains.

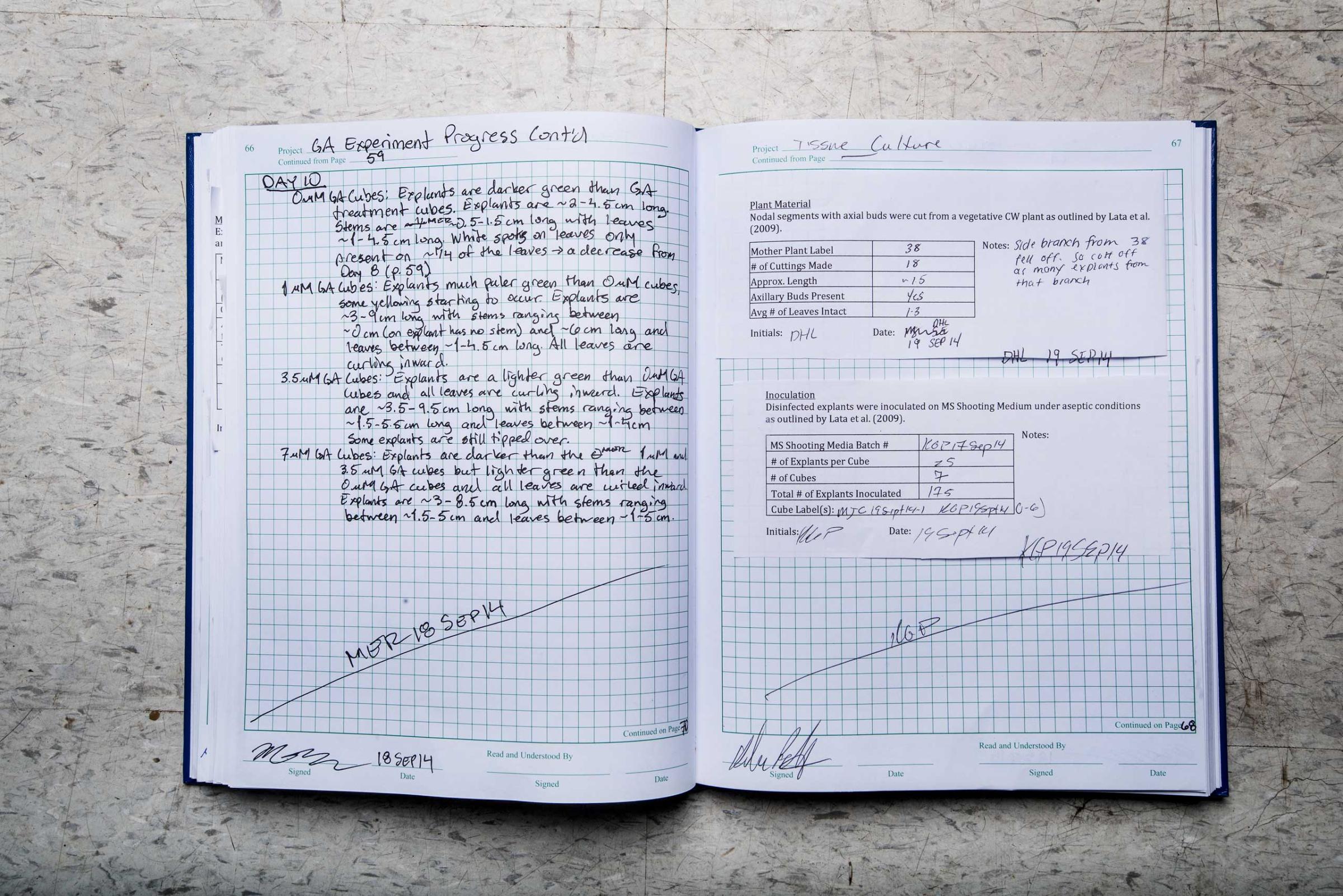

In one experiment, Hurd’s rats spent their adolescence getting high, on regular doses of tetrahydrocannabinol (THC), the psychoactive compound in marijuana. In the past, scientists have found that rats exposed to THC in their youth will show changes in their brain in adulthood. But Hurd asked a different question: Could parental marijuana exposure pass on changes to the next generation, even to offspring who had never been exposed to the drug?

So she mated her rats, but only after she had waited a month to make sure the drug was no longer in their system. She raised the offspring, along with another group of rats that shared the same life experiences except for the THC. She then trained the children to play a game alone in a box. The prize: heroin.

Press one lever to get a shot of saline into the jugular vein. Press the other to get a rush of opiates. Initially, the rats with THC-exposed parents performed about the same as the rats with sober parents. But when Hurd’s team changed the rules, requiring the rats to work harder for the drug, differences emerged. The rats with drug-using parents pushed the lever more than twice as much. They wanted the heroin more.

When she analyzed the brains of the rats, she also found differences in the neural circuitry of the ones with drug-using parents. Even the grandkids have begun to show behavioral differences in how they seek out rewards. “This data tells us we are passing on more things that happen during our lifetimes to our kids and grandkids,” Hurd explains, though it remains unclear how those changes manifest in humans. “I wasn’t expecting these results, and it’s fascinating.”

Welcome to the encouraging, troubling and strangely divided frontier of marijuana science. The most common illicit drug on the planet and one of the fastest-growing industries in America, pot remains–surprisingly–something of a medical mystery, thanks in part to decades of obstruction and misinformation by the federal government. Potentially groundbreaking studies on the drug’s healing powers are being done to find treatments for conditions like epilepsy, posttraumatic stress disorder (PTSD), Alzheimer’s disease, Parkinson’s disease, sickle-cell disease and multiple sclerosis. But there are also new discoveries about the drug’s impact on recreational users.

The effects are generally less severe than those of tobacco and alcohol, which together cause more than 560,000 American deaths annually. Unlike booze, marijuana isn’t a neurotoxin, and unlike cigarettes, it has an uncertain connection to lung cancer. Unlike heroin, pot brings almost no risk of sudden death without a secondary factor like a car crash. But science has also found clear indications that in addition to short-term effects on cognition, pot can change developing brains, possibly affecting mental abilities and dispositions, especially for certain populations. The same drug that seems relatively harmless in moderation for adults appears to be risky for people under age 21, whose brains are still developing. “It has a whole host of effects on learning and cognition that other drugs don’t have,” says Jodi Gilman, a Harvard Medical School researcher who has been studying the brains of human marijuana users. “It looks like the earlier you start, the bigger the effects.”

Beyond Reefer Madness

That relatively measured tone is a far cry from the shrill warnings of Harry J. Anslinger, the first commissioner of the Federal Bureau of Narcotics, who in the 1930s set the standard for America’s fraught debate over marijuana with wild exaggerations. “How many murders, suicides, robberies, criminal assaults, holdups, burglaries and deeds of maniacal insanity it causes each year, especially among the young, can only be conjectured,” he wrote as part of a campaign to terrify the country. As recently as the 1970s, President Richard Nixon talked about the drug as a weapon of the nation’s enemies. “That’s why the communists and the left-wingers are pushing the stuff,” he was recorded saying in private. “They’re trying to destroy us.”

The official line today is better grounded in data and research. And the new focus is squarely on brain development. “I am most concerned about possibly harming the potential of our young people,” says Dr. Nora Volkow, the head of the National Institute for Drug Abuse (NIDA), which funds Hurd’s and Gilman’s work. “That could be disastrous for our country.”

Meet Colorado's Pot Smokers

But decades of prohibition and official misinformation continue to shape public views. “The government did not spend as much effort in finding out the facts about marijuana,” says Hurd. “That strategy of scaring people rather than provide knowledge has made people skeptical now when they hear anything negative.”

As states now rush to legalize pot and unwind a massive criminalization effort, the federal government is trying to play catch-up on the science, with mixed success. The only federal marijuana farm, at the University of Mississippi, has recently expanded production with a $69 million grant in March, and Volkow has expressed a new openness to studies of marijuana’s healing potential. In the coming months, Uncle Sam will begin a 10-year, $300 million study with thousands of adolescents to track the harm that marijuana, alcohol and other drugs do to the developing brain. High-tech imaging will allow researchers for the first time to map the effects of marijuana on the brain as humans age.

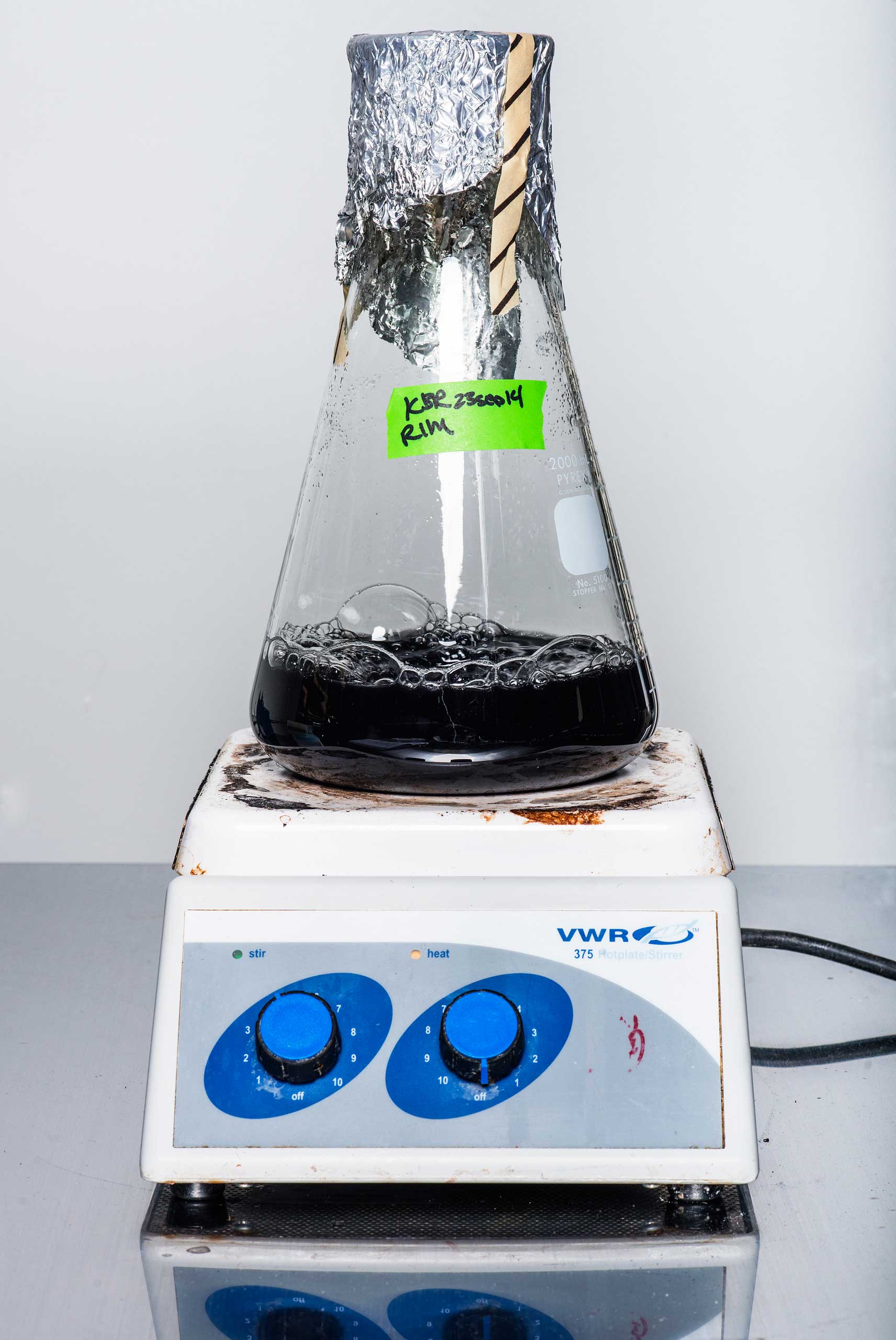

But scientists and others point out that a shift to fund the real science of pot still has a long way to go. The legacy of the war on drugs haunts the medical establishment, and federal rules still put onerous restrictions on the labs around the country that seek to work with marijuana, which remains classified among the most dangerous and least valuable drugs. “We can do studies on cocaine and morphine without a problem, because they are Schedule II,” explains Fair Vassoler, a researcher at Tufts University who has replicated Hurd’s rat experiment with synthetic pot. “But marijuana is Schedule I.”

That means that under the law, marijuana has “no medical benefit,” even though 23 states have legalized pot as medicine and NIDA acknowledges that “recent animal studies have shown that marijuana can kill certain cancer cells and reduce the size of others.” And marijuana researchers face barriers even higher than those faced by scientists studying other Schedule I drugs, like heroin and LSD. Pot studies must pass intensive review by the U.S. Public Health Service, a process that has delayed and thwarted much research for more than 15 years. The result is sometimes a catch-22 for scientists seeking to understand the drug. “The government’s research restrictions are so severe that it’s difficult to find and show the medical benefit,” says neurobiologist R. Douglas Fields, the chief of the nervous-system-development section at the National Institutes of Health (NIH).

That all may change soon. On Capitol Hill, a left-right coalition of Senators Kirsten Gillibrand of New York, Rand Paul of Kentucky and Cory Booker of New Jersey introduced a bill in March to federally legalize medical marijuana in states that have already approved it. “For far too long,” said Paul, a Republican candidate for President, “the government has enforced unnecessary laws that have restricted the ability of the medical community to determine the medicinal value of marijuana.”

Go Inside the Harvest of Colorado's Most Controversial Marijuana Strain

The Cannabinoid System

Harm researchers and neuroscientists aren’t completely deadlocked. They agree on at least one thing. Marijuana’s positive and negative effects both spring from the same source: the body’s endocannabinoid system. First discovered in the late 1990s, it’s a complex neural system that researchers are only beginning to fully comprehend.

A little Brain Science 101: Human gray matter contains around 86 billion neurons, a type of cell that essentially talks to other cells in the brain through electrochemical processes. Neurons talk to each other through chemical messengers known as neurotransmitters–including dopamine, serotonin, glutamate and compounds called endocannabinoids–which in turn send instructions to your body about what to do.

Researchers now know the body produces endocannabinoids, which activate cannabinoid receptors in the brain. Interestingly, one plant on earth produces a similar compound that hits those same receptors: marijuana. Just as poppy-derived morphine mimics endorphins, marijuana-derived cannabinoids like THC and cannabidiol (CBD) mimic endocannabinoids, which impact feelings of hunger and pleasure. Cannabinoid receptors are especially widespread in the brain, where they play a key role in regulating the actions of other neurotransmitters.

“The more we investigate the hidden recesses of the brain, the more it seems like practically every neuron either releases endocannabinoids or can sense them using cannabinoid receptors,” explains Gregory Gerdeman, a neuroscientist and endocannabinoid researcher at Florida’s Eckerd College. Neurotransmitters carry out brain communication through synapses. “But too much synaptic excitation is poisonous–it damages cells,” says Gerdeman. “Endocannabinoids are a mechanism for putting on the brakes when that toxic level of excitation is approached.”

Cannabinoids like CBD may be thought of as neuroprotectants–that is, brain protectors. In fact, the NIH actually owns a patent (No. 6630507) on cannabinoids as neuroprotectants, based on the work of researcher Aiden Hampson and his mentor, Nobel Prize–winning neuroscientist Julius Axelrod. They found that CBD showed particular promise in limiting neurological damage in patients with Alzheimer’s disease and Parkinson’s disease and in those who have suffered a stroke or head trauma.

Endocannabinoids also play a role in the regulation of pain, mood, appetite, memory and even the life and death of individual cells. Curiously, cannabinoid receptors aren’t densely packed in the medulla (within the brain stem), which controls breathing and the cardiovascular system. That’s why a heroin overdose can be fatal–the drug shuts down the respiratory control center–but a marijuana overdose generally can’t. PTSD researchers are keen to crack the cannabinoid code because the compounds appear to play a role in extinguishing unpleasant memories. “Part of what happens with PTSD is that the brain’s stress buffers have been blown out by trauma,” says Gerdeman. “Endocannabinoids within the amygdala”–the brain region important for emotional learning and memory–“act as a key mechanism for what we call memory extinction.”

But what accounts for the potentially healing effects of pot in some can cause harm in others. That’s because endocannabinoids appear to play a critical role in the development of the adolescent brain. If the brain were a house, the childhood years would be spent pouring the foundation and framing up the walls. Adolescence is when the wiring and plumbing get finished. Neural networks are refined and strengthened through pruning. The strong synapses, axons and dendrites are preserved, the weak culled.

Researchers now believe the cannabinoid system plays a critical role in this neural fine-tuning. This is where the worries about teenage pot use come to the fore. At the precise moment when the brain relies on a finely calibrated dose of endocannabinoids, the adolescent weed smoker floods the system. “If you actively and repeatedly overload the endogenous cannabinoid system,” says Volkow, “you are going to disrupt that very well-orchestrated system.”

That disruption may lie at the heart of still inconclusive science about marijuana’s impact on human behavior, especially among younger users. Early studies suggest that there may be long-lasting impacts on mental acuity, higher brain function and impulse control for younger users. There is also a well-documented connection between pot smoking and schizophrenia, a condition that affects about 1% of the U.S. population. Scientists have been aware of the link since the 1970s. Among those with a family history of mental illness, marijuana can hasten the emergence of schizophrenia.

Researchers are trying to identify the mechanisms in play. “Many genes are undoubtedly involved in risk for schizophrenia,” says Dr. Michael Compton, a professor at Hofstra North Shore–LIJ School of Medicine and the head of psychiatry at New York City’s Lenox Hill Hospital. “But there are also a host of social or environmental influences at work.” For a subset of the population, the earlier the initiation of marijuana use, the earlier the onset of psychosis.

Here’s why that matters: The later schizophrenia emerges, the greater the likelihood of recovery. Schizophrenia onset in a 15-year-old is often permanently life-altering. In a 24-year-old, it can be less damaging, because the person has had the chance to accomplish more psychological and social-developmental milestones. But that doesn’t mean all teenage pot users are smoking themselves into mental illness. Darold Treffert, the Wisconsin psychiatrist who first documented the marijuana-schizophrenia link in the 1970s, puts it this way: “Perhaps some persons can safely use marijuana, but schizophrenics cannot.” A test or a clear genetic marker to identify kids who are vulnerable to schizophrenia is likely years away.

The Healing Possibilities

While American research on the potential harms from marijuana is booming, the U.S. continues to lag in funding investigations into the possible benefits. In the late 1990s, the U.S. and British governments commissioned separate studies of medical marijuana. The U.K. study was spurred by multiple-sclerosis patients’ using pot to calm spasticity. The U.S. study, done by the Institute of Medicine, was in response to California’s 1996 legalization of medical marijuana.

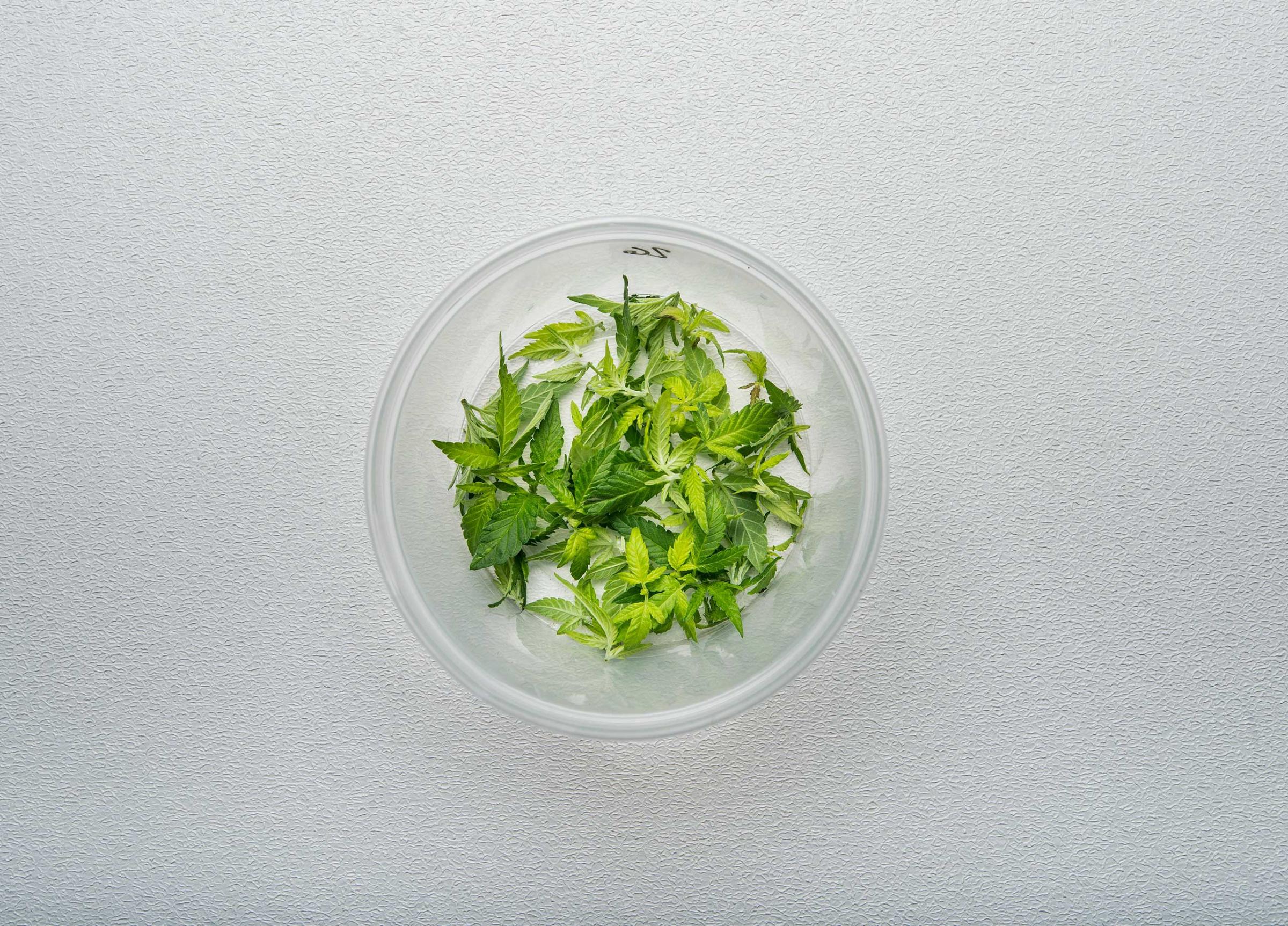

Both studies reached a similar conclusion: medical pot wasn’t a hippie’s delusion. The research showed that the stuff held real therapeutic potential for specific conditions, including epilepsy, chronic pain and glaucoma. The British responded by treating marijuana as a plant with biotech prospects. U.K. officials licensed GW Pharmaceuticals, a startup lab in Salisbury, England, to grow weed and develop cannabinoid drugs, some of which U.S. scientists like Hurd use in their research.

The Americans, meanwhile, doubled down on the war on drugs. Barry McCaffrey, Bill Clinton’s drug czar, was outraged at the Institute of Medicine’s results. “I think what the IOM report said is that smoked marijuana is harmful, particularly for those with chronic conditions,” he said–pretty much the opposite of the report’s conclusions. Nonetheless, he and then Attorney General Janet Reno vowed to prosecute medical-marijuana patients and doctors who prescribed the drug. Shortly thereafter, the U.S. Department of Health and Human Services adopted even tougher strictures against the study of marijuana as a medicine.

The federal antipot policies resulted in a strange kind of scientific trade deficit. The U.S. leads the world in studies of marijuana’s harm, but we’re net importers of data dealing with its healing potential. THC discoverer Raphael Mechoulam runs the world’s leading cannabinoid lab at the Hebrew University of Jerusalem. Spanish biologist Manuel Guzmán is doing cutting-edge work on the potential of cannabinoids to retard the growth of glioblastoma, one of the deadliest forms of brain cancer. Canada’s health agency may soon approve the world’s first clinical trial to test medical marijuana on military and police veterans with PTSD.

There are signs of change at home, though. This year, the Colorado department of public health awarded $9 million in grants for medical-marijuana research, funded with tax revenue from state-licensed pot stores. They will be among the first U.S. clinical trials to look into the effectiveness of marijuana for childhood epilepsy, irritable-bowel disease, cancer pain, PTSD and Parkinson’s disease. Dr. Kelly Knupp, a pediatric-epilepsy specialist at Children’s Hospital in Denver, will track children using high-CBD marijuana strains to calm seizures. “Some of these children can have 100 to 200 seizures a day,” Knupp says. “We’re hoping we can measure seizure frequency to see if there’s any improvement” among kids trying the cannabinoid medicine.

This Is a Rat on Drugs

Back at Hurd’s Upper East Side lab, the rats have begun to show the way. In a separate experiment, she gave heroin-addicted rats doses of CBD and found that it decreased their willingness to work hard for more heroin, suggesting that parts of marijuana could help human drug addicts stay clean. She is now testing that hypothesis by giving CBD tablets, made in England, to recovering human addicts in New York City.

She is also continuing to study the behavior of rats whose only exposure to marijuana’s active ingredients came through the DNA passed on to them from their parents or grandparents. That research suggests that THC may have epigenetic effects, which have been found in other drugs like cocaine and heroin, changing the way genes express themselves in the brains of offspring. This doesn’t necessarily mean that parents who smoked weed in high school have damaged their kids, because those changes may be overrun by other behaviors. The science is too new to know for sure. “It’s not a given that this is going to happen,” Hurd explains of her rats. “They tell us the potential.”

That word–potential–still qualifies much of what is known about pot, but it won’t be that way for long. The science of pot is likely to expand in the coming years, and it could boom if federal restrictions are lifted. What the government once dismissed as a communist plot that prompted murderous rages has turned out to be a window into the very workings of the human mind. In the years to come, researchers may yet find genetic markers that predispose people to pot-induced psychotic reactions, map out the specific ways in which THC changes the brain and find new medicines for some of the most intractable illnesses. Until then, the great marijuana experiment will continue in a country where 1 in 10 adults–and 35% of high school seniors–admit to conducting their own, mostly recreational, research.

Barcott is a journalist who has contributed to the New York Times, National Geographic and other publications. Scherer is TIME’s Washington bureau chief. Portions of this article were adapted from Barcott’s new book Weed the People: The Future of Legal Marijuana in America, published by TIME Books.

More Must-Reads From TIME

- The 100 Most Influential People of 2024

- Coco Gauff Is Playing for Herself Now

- Scenes From Pro-Palestinian Encampments Across U.S. Universities

- 6 Compliments That Land Every Time

- If You're Dating Right Now , You're Brave: Column

- The AI That Could Heal a Divided Internet

- Fallout Is a Brilliant Model for the Future of Video Game Adaptations

- Want Weekly Recs on What to Watch, Read, and More? Sign Up for Worth Your Time

Contact us at letters@time.com