The mastermind behind the super PAC has no regrets. “My only regret is the backlash,” David Keating says with a wry smile.

Keating is one of the most influential political activists you’ve never heard of. He was the architect of a federal lawsuit that ended in a landmark 2010 court ruling that reshaped the way elections are run. The case, SpeechNow.org vs. FEC, scrapped annual limits on individual contributions to campaign advocacy groups, ushering in the era of super PACs—political-action committees that can raise unlimited sums as long as they don’t coordinate directly with parties or candidates.

Five years later, campaigns are only beginning to harness the power of Keating’s creation. In the 2016 presidential race, virtually all of the candidates will have companion super PACs, many of which will wield more influence than the campaigns themselves. Candidates have leveraged super PACs to supercharge fundraising, pay for staff salaries and trips to primary states and even assume the duties once reserved for the campaigns themselves, from running TV ads and organizing supporters to direct mail campaigns and digital microtargeting.

Many of these innovations have surprised Keating, a soft-spoken man with a graying beard. But he delights in watching how, year by year, political strategists are using super PACs to refine the mechanics of elections. Using a super PAC specifically to promote a candidate “just never entered my mind,” he says. “But it’s totally obvious when you think about it.”

Not everyone is so sanguine about the impact of his creation. Political critics, campaign-finance watchdogs and even some candidates argue that super PACs have invited an avalanche of outside spending that gives the wealthy outsize influence and makes a mockery of the limits established by the FEC.

“We need to fix our dysfunctional political system and get unaccountable money out of it once and for all,” Democratic frontrunner Hillary Clinton said recently. But it’s a sign of the super PAC’s power that Clinton has nonetheless embraced a group of her own. Despite her stated objections, she plans to personally court influential donors, according to the New York Times.

Keating celebrates such changes. A longtime conservative activist, he believes in an unfettered right to political speech, and decries caps on campaign donations as an infringement of First Amendment rights. Now the president of the Center for Competitive Politics, an independent group that works to loosen campaign-finance regulations, he says his mission was “to do for the First Amendment what the NRA did for the Second.”

Keating casts super PACs as a better way for ordinary citizens to organize and exercise their First Amendment rights. “It comes down to speech,” he says. “If you don’t like [others’] speech, start your own group and talk to people.” And he argues a system that allows the super-rich to pump a gusher of cash into elections is a testament to a thriving democracy.

“That’s how we elected all our great presidents,” he told TIME in an interview Tuesday in his office in Alexandria, Va., ticking off leaders from Lincoln to Eisenhower who took office after elections held under looser campaign-finance regulations. “Rich people have always had the ability to spend whatever they want.”

SpeechNow came on the heels of Citizens United, its more-celebrated brethren in the annals of campaign-finance deregulation. “After Citizens, our case became a total slam dunk,” he says. Though lesser known, SpeechNow significantly widened the impact of Citizens, making it the arguably the more important of the two landmark cases. The combination paved the way for an election that has already seen significant evolutions in super PAC usage.

The two most interesting innovations in 2016, Keating says, have been the quartet of interlinked super PACs backing Texas Sen. Ted Cruz and the approach taken by former Florida Gov. Jeb Bush, who has delayed his campaign launch to stockpile his Right to Rise PAC. The group has effectively supplanted Bush’s campaign-in-waiting as the hub of his political operation. “What Jeb is doing takes a lot of discipline” due to the prohibitions on direct coordination, Keating notes, though says he is confident that Bush’s lawyers have kept him on the right side of the law.

Though a staunch conservative—he was formerly an executive at groups like the National Taxpayers Union and the Club for Growth—Keating appears to admire the political innovations of the super PAC era no matter where they come from. He notes that Correct the Record, a research group originally formed to defend Clinton, has relaunched as a pro-Clinton super PAC that says it is able to coordinate with the likely Democratic nominee because it will restrict itself from paid media campaigns.

“Here is another innovation–a Super PAC that can legally coordinate with a candidate,” he wrote in an email Tuesday evening. “The reason why they can do that is because they will not make any public communications, as defined in the regulations. Mass mailings do not include e-mail.

“Clever,” he concluded.

But maybe not. About an hour later he emailed again. “This … issue is actually pretty complicated,” he noted, “and it’s not clear they can do what they say they want to do. There isn’t enough detail about their plans to determine if what they plan to do is OK or not.”

It seemed a fitting testament to the murkiness of this new campaign-finance landscape that even its creator can’t always be sure what’s legal.

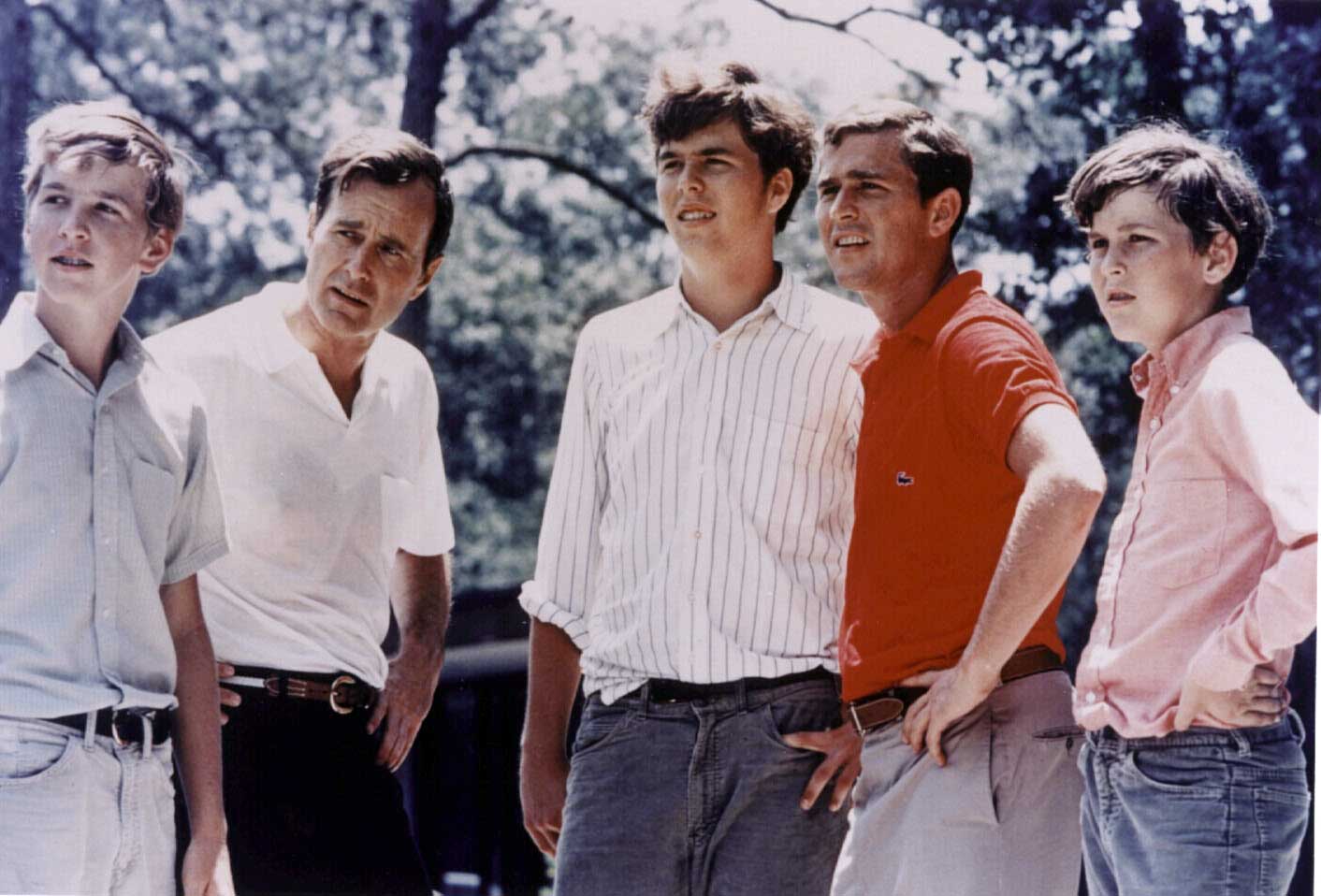

Photos: Meet America's Top 10 Political Families

More Must-Reads from TIME

- Why Trump’s Message Worked on Latino Men

- What Trump’s Win Could Mean for Housing

- The 100 Must-Read Books of 2024

- Sleep Doctors Share the 1 Tip That’s Changed Their Lives

- Column: Let’s Bring Back Romance

- What It’s Like to Have Long COVID As a Kid

- FX’s Say Nothing Is the Must-Watch Political Thriller of 2024

- Merle Bombardieri Is Helping People Make the Baby Decision

Write to Alex Altman at alex_altman@timemagazine.com