David Cameron, the British Prime Minister, traveled to Buckingham Palace on Friday where the Queen asked him to form a new government. Unlike in 2010, Cameron’s Conservative Party will be able to govern without the help of a coalition partner.

A jubilant Cameron told supporters that he did not expect this success. “We are on the brink of something so exciting,” he said. But elsewhere, British politics resembled a particularly bloody episode of Game of Thrones as the leaders of three major parties resigned before Friday lunchtime.

Cameron’s euphoria may be shortlived as he now has to deal with two problems he was instrumental in creating. Before the election, he said he would renegotiate the U.K’s membership of the European Union and then put that membership to a referendum by the end of 2017. Cameron also infuriated Scottish and English voters alike by warning of the dangers of a powerful Scottish National Party, which could have been the Labour Party’s ally in government if Labour had performed better on Thursday.

The Prime Minister’s rhetoric increased support for the SNP at the expense of Labour (the Conservative Party has had little representation in Scotland in the last 30 years) and bolstered Conservative support at the expense of Labour in England. Labour supporters said, with some justification, that they failed because they were squeezed by two nationalisms, Scottish and English.

The issues of Europe and Scotland may have given the Conservatives short-term electoral gain but could end up dominating their next five years in power.

Scotland voted against independence in 2014 but on Thursday the Scottish National Party won 56 out of 59 seats in Scotland, an unprecedented victory. The SNP did not campaign for independence but on economic policies that directly contradict what the Conservatives stood for in England. Alex Salmond, the former leader of the SNP, told voters: “It is inconceivable that such a statement by the Scottish people could be ignored.”

Cameron, who says he is passionately in favor of keeping Scotland in the U.K., will have little choice but to tailor and vary his policies to suit Scotland or risk a constitutional crisis. This could in turn create antagonism against Cameron and Scotland in England where many people are likely to resent any special treatment given to Scotland.

To create the ideal atmosphere for Scottish independence, it could be in the SNP’s best interests for the relationship between Scotland and the rest of the U.K. to break down. Cameron will have to resist exacerbating these divisions, which could further galvanize English nationalism.

U. K. defence policy will also be impacted by the success of the SNP, which was elected on a platform of rejection of the U.K.’s ballistic nuclear program that is wholly based in the Clyde Estuary in Scotland. Trident is due to replaced over the course of the next parliament but renewal and the continued siting of the nuclear base in Scotland will likely become a bone of continued contention because it has been rejected so strongly by the Scottish electorate.

The Conservatives face equal difficulties over Europe. The French newspaper Le Monde captured the view of Europe to Cameron’s success. “Cameron’s triumph: worry in Europe,” its headline ran.

Cameron said he wants to re-negotiate parts of the treaties governing the U.K.’s membership of the E.U., in particular the primacy of the European Court of Human Rights and the policy that provides the freedom of movement of labor, before putting the membership of the E.U to a referendum in 2017.

Both the re-negotiation and the referendum will antagonize European allies and business leaders, natural allies of Cameron, and will probably not go far enough to appease the anti-E.U. wing of his party.

Christopher Howarth, a senior policy analyst at Open Europe, a think tank, said E.U. nations may be willing to accomodate Cameron to a certain extent but businesses and financial markets would not be pleased. “Markets and the economy traditionally don’t like uncertainty. Holding a referendum potentially creates some uncertainty, particularly around the result and what the result would mean,” he says.

The success of the Conservatives is partly attibutable to to their adoption of an E.U. referendum, which was the policy of the rightist United Kingdom Independence Party (UKIP). This manoeuvre appears to have stopped UKIP from achieving much success on Thursday. It held one of its two seats and UKIP’s charismatic leader, Nigel Farage, failed to get elected. Farage is one of the three parties leaders to have resigned. (The leader of the centrist Liberal Democrats, Nick Clegg, has also resigned after his party suffered substantial losses.)

UKIP’s failure belies its popularity; it received 3.5 million votes but because of the electoral system this did not translate into seats in parliament. UKIP members have already started complaining about the British “first-past-the-post” system of electing a government and may start campaigning for European-style proportional representation.

The possibility of the Conservatives’ difficulties over Scotland and Europe will be a light at the end of a dark tunnel for the Labour Party. Ed Milliband resigned as the party leader after he failed to stop Cameron forming the next government. The party will have to find a new leader and work out why they were trounced in Scotland and why their policies did not resonate enough with English voters.

Watching Cameron wrestle with the challenges of Europe and Scotland will be a small consolation for the battered, disappointed Labour Party.

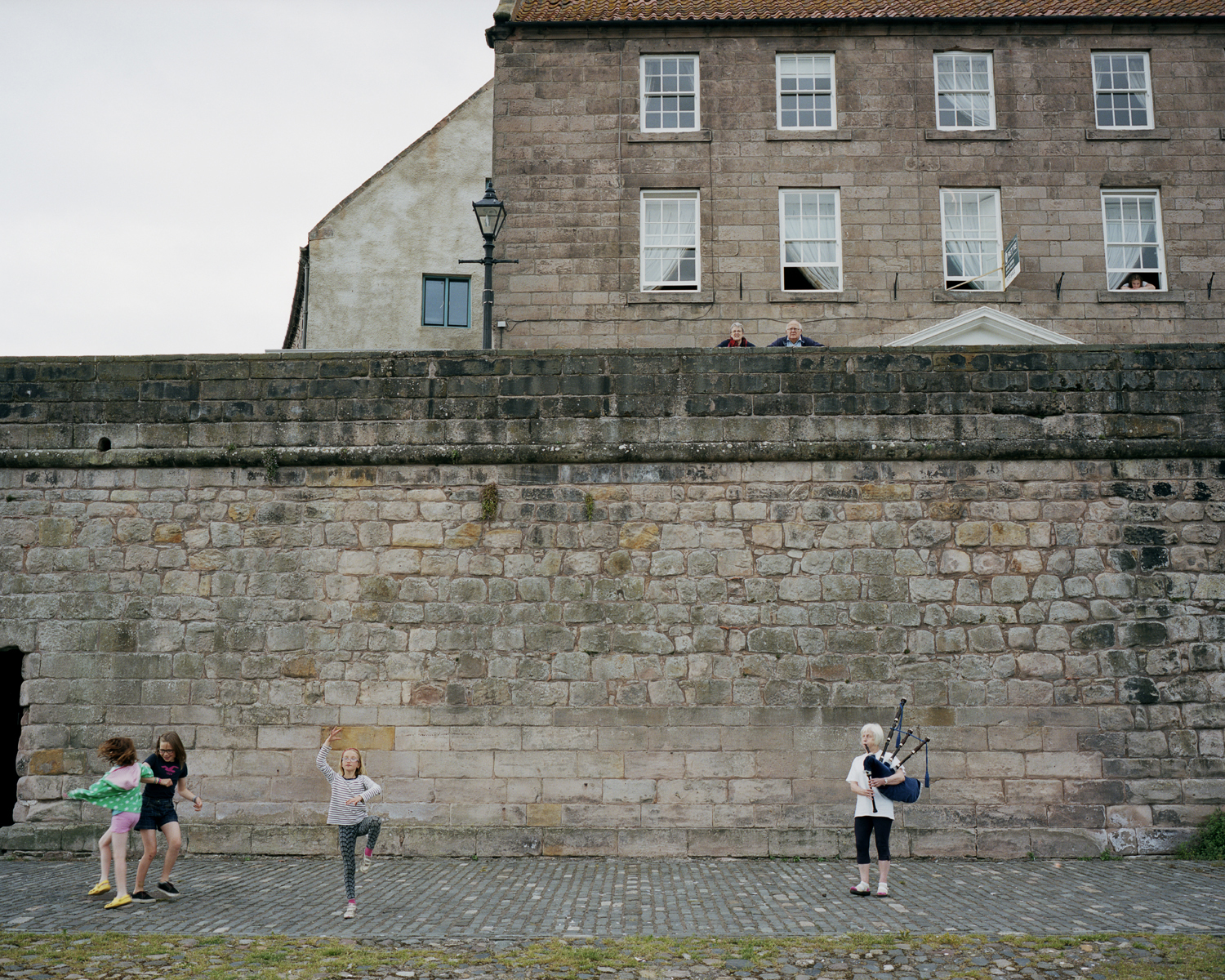

Visit England’s Strange Border With Scotland

More Must-Reads from TIME

- Cybersecurity Experts Are Sounding the Alarm on DOGE

- Meet the 2025 Women of the Year

- The Harsh Truth About Disability Inclusion

- Why Do More Young Adults Have Cancer?

- Colman Domingo Leads With Radical Love

- How to Get Better at Doing Things Alone

- Michelle Zauner Stares Down the Darkness

Contact us at letters@time.com