At 19 days old, Zain Rajani looks like an ordinary baby boy. He is anything but.

His parents, Natasha, 34, and Omar Rajani, 39, of Toronto, spent four years trying to get pregnant. Now they’ve produced the first baby in the world born using a breakthrough in vitro fertilization technique that could dramatically improve the success rate of IVF.

The approach is still being tested–and is controversial to some, not least for its dependence on a type of human stem cell. Many experts, however, are excited by the potential of the technique, called Augment, because it relies on cells that are already present in a woman’s ovaries. It uses the pristine stem cells of healthy, yet-to-develop eggs to try to help a woman’s older eggs act young again. And unlike other kinds of stem cells, which have the ability to develop into any kind of cell in the body–including cancerous ones–these precursor cells can form only eggs.

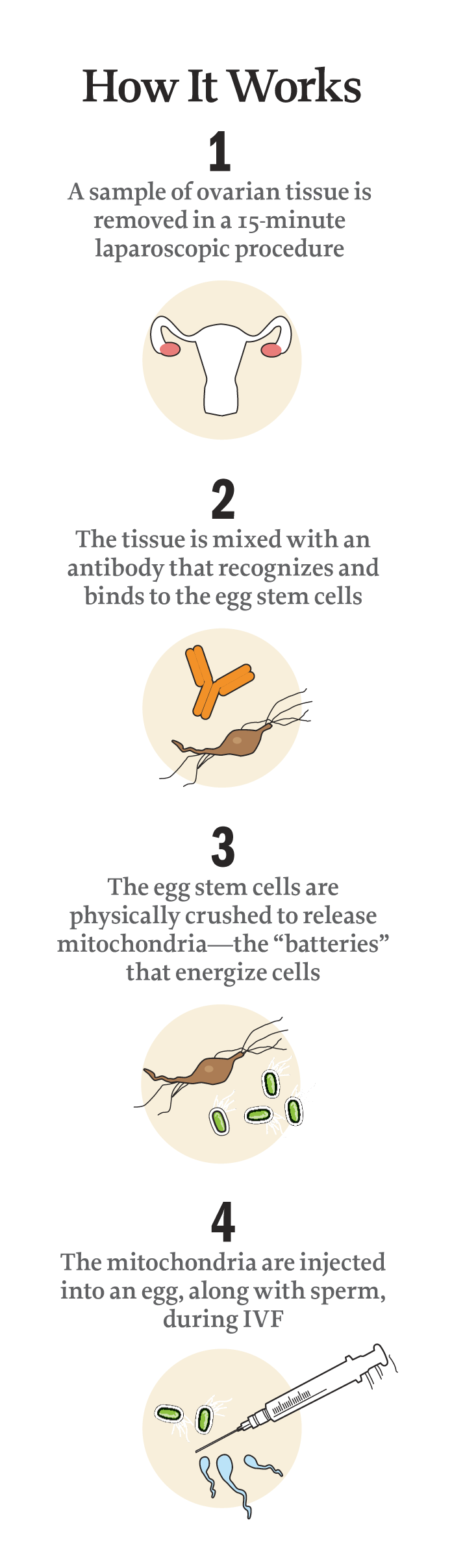

The Rajanis, who spoke exclusively with TIME, say that’s why Zain is here. In May 2014, in a quick laparoscopic procedure, scientists collected a sample of Natasha’s ovary cells and distilled it to a clear liquid containing mitochondria from the egg precursors. Mitochondria are cells’ energy source, acting almost like batteries that help them function. So when the liquid produced from Natasha’s cells was combined with her eggs, it essentially recharged them, energizing the fertilization process. The result: four healthy embryos, one of which was implanted into her uterus and ultimately developed into baby Zain.

This process yielded a “night-and-day difference” in the number of strong embryos the couple produced compared with their traditional IVF cycle, says Dr. Marjorie Dixon, their doctor at First Steps Fertility, a private clinic in Toronto. That time, just 4 of the 15 eggs retrieved became fertilized, and though one was transferred, it didn’t take.

Now Zain is the first in a wave of babies expected to be born throughout the summer using the same method. So far, nearly three dozen 30-something women in four countries have tried Augment, and so far, eight are pregnant. All of them have had at least one unsuccessful cycle of traditional IVF; some have had as many as seven. If Augment’s early promise is borne out, it could transform the outcomes of the estimated 176,000 IVF cycles reported in the U.S. each year, whose costs start at anywhere from $15,000 to $20,000 per cycle.

The approach emerged in large part from a 2004 breakthrough by Jonathan Tilly, then a biologist at Harvard Medical School and now chair of biology at Northeastern University. He discovered that some cells from the outer surface of the ovary contain just what many women need: a more reliable source of mitochondria to support the poor egg quality that can make a pregnancy challenging.

“The technique addresses a void in IVF,” says Tilly–the need to help women whose eggs can’t be fertilized effectively. “We are taking patients with a 0% pregnancy rate, patients who have failed IVF because of poor egg quality, and getting them pregnant.”

By making that possible, OvaScience, the company Tilly co-founded to bring the proprietary technique to patients, is embarking on what could prove to be a very profitable venture. Critics worry that it’s a case of the fertility industry racing ahead without sufficient evidence of how well a procedure works; the method has not yet been approved in the U.S. But the scientists behind it believe they are poised to launch the next major evolution in IVF.

New and Improved IVF

Augment’s supporters have a point. Zain’s birth represents the first major advance in reproductive assistance since 1978, when Louise Brown, the first IVF baby, was born to headlines that declared the age of the “test-tube baby” had arrived.

Since that time, scientists have made incremental improvements to the process. They fine-tuned a recipe for the nutrient bath they use for fertilization, and they’ve improved the way they nurture the embryos. But taken together, these advances have nudged pregnancy rates upward by only a percentage point or two over the course of 35 years. As it stands, the IVF success rate is about 38% for women in their late 30s and 18% for women in their early 40s. And today the procedure looks very similar to the one used to produce Brown–complete with weeks of hormone injections and daily doctor’s visits for blood tests and ultrasound scans.

Stem-cell-based techniques like Augment, co-developed by Tilly and Harvard Medical School aging expert David Sinclair, could change that. Women will still need the rounds of hormone shots to produce more than one egg during a cycle. But it will be possible, scientists think, to not only boost those eggs with stem cells–as Natasha’s doctors did–but also to coax egg stem cells inside the mom-to-be into fully mature eggs, giving her a fresh, more viable supply that she can use to become pregnant, either naturally or with IVF. (That procedure may be available from OvaScience by the end of the year.)

“We could be on the cusp of something incredibly important,” says Dr. Owen Davis, president-elect of the American Society for Reproductive Medicine (ASRM), who is not affiliated with OvaScience. “We could be on the brink of something that is really going to pan out to be revolutionary.” But as with any major scientific breakthrough, regulatory questions, the need for more data and some vocal critics will first have to be addressed.

For Natasha, who works in strategic sourcing for a Canadian drug-store chain based in Toronto, the journey to motherhood began a year after she and Omar were married in 2010. When they couldn’t get pregnant on their own, they tried prescription medications, including Clomid, which prompts the growth of mature eggs. They also tried intrauterine insemination and consulted with a naturopath. Natasha got pregnant once but miscarried a few weeks later. Feeling like they’d exhausted their other options, they decided to try IVF last year. But even that proved disappointing.

“Having to go in every morning to do blood work and ultrasounds and then head off to work was a bit taxing,” Natasha says. “I tried to remain positive, thinking there is a light at the end of the tunnel and that a baby will be there at the end.”

During her first go at IVF, she produced an impressive number of eggs–more than a dozen–but they weren’t robust enough to form embryos that were sufficiently healthy to transfer. “The quality of embryos was not good at all,” says Dixon, her physician at First Steps Fertility. One embryo was almost mature enough to transfer, Dixon says, so they went for it. “I knew it wasn’t the best-quality embryo, but it was what she had.” It didn’t work.

When Natasha expressed a desire to try IVF again, Dixon wanted to improve her odds and proposed that she consider the Augment technique, which was being tested at the clinic. Because the procedure is so new, OvaScience says, it was offered to its first group of women for free so the company could study its effects. (OvaScience is now starting to charge clinics $15,000 to $25,000 for the Augment service.)

“I was ecstatic to know that there was something else we could try,” says Natasha. Within three weeks, Dixon had removed a sample of tissue surrounding Natasha’s ovary. That sample was then treated by OvaScience-trained lab technicians, who used a proprietary process to find and remove the egg stem cells and then punch out their mitochondria. “Anything present in an egg comes from these cells,” says Tilly. “So it’s logical to think of them as a natural source of eggs.”

What makes these cells so enticing to scientists–and different from other fertility advances–is that they come from the mother herself. Mitochondria contain their own DNA, separate from a person’s genome. In a recent controversial decision, the U.K. approved so-called three-person babies, where mitochondrial DNA from a healthy woman is introduced into the egg of a woman with mitochondrial disease. If that egg results in a live birth, it can raise ethical questions, biological concerns and conflicts about parenthood. With the Augment technique, however, the cells are all from the mother’s ovaries.

The key to Augment is breaking down the egg stem cells and pulling out a concentrated solution of mitochondria. When embryos are formed, it’s the mitochondria, some experts believe, that fuel the cell divisions that eventually produce the complex, multicelled organism that is a human baby.

“When you’re 40, your eggs are 40,” says Dr. Robert Casper, a professor of obstetrics and gynecology at the University of Toronto and an adviser for OvaScience. He performed the first procedures using the technique, including overseeing Natasha’s cycle. “Adding mitochondria from the egg precursor cells is like putting fresh batteries into a flashlight,” he says.

A similar discovery came in 2001, when Jacques Cohen, a fertility specialist at St. Barnabas Medical Center in New Jersey, did a study combining the non-DNA contents of younger eggs with older women’s eggs. That process appeared to rejuvenate the eggs and resulted in about 50 babies born using the technique. But the FDA said the procedure was a form of gene therapy–which the agency regulates–and required additional studies on its safety. The studies were never done, and the technique was effectively scrapped altogether in the U.S.

The FDA’s requirement for data is keeping Augment out of the U.S. as well–at least for now. OvaScience plans to perform about 1,000 cycles this year and hopes that the data will help make the case for the technique stateside. “There is always early skepticism, but we need to generate the data and have healthy live babies,” says Arthur Tzianabos, the company’s president.

Waiting for Data

The lack of robust data is the main concern of Augment’s critics. Some fertility scientists question whether mitochondria are indeed the silver bullet they seem to be. What’s lacking, critics say, is convincing evidence that compares pregnancy rates of women undergoing Augment with those of women who have similar infertility problems but haven’t used the technique. So far, no formal scientific trials have been conducted; the only data on the procedure comes from presentations by Casper and Dr. Kutluk Oktay, from Gen-ART IVF in Ankara, Turkey–both of whom are advisers to OvaScience.

“We’re not yet sure the scientific model has proved what the outcomes would be if you use the mitochondria of a younger egg or from an egg stem cell,” says ASRM’s Davis. “It’s a fascinating concept, but we just haven’t seen the studies yet.”

In the world of infertility, however, such data is historically hard to come by. For one thing, poor egg quality, which Augment addresses, is a leading cause of infertility, but there is still much that isn’t known about why some women can’t get pregnant. Meanwhile, a lack of regulation of most reproductive technologies–the ones that don’t fall under the jurisdiction of the FDA as either drugs, devices or gene therapy–and the dominance of business-minded scientists have led to some new methods being rushed to clinics, often before their effectiveness has been fully proved. Fertility clinics have been required to report on their success rates only since 2012, and some still don’t provide this data, so parents-to-be don’t always have objective ways to gauge the quality of the costly services they’re buying.

“The people providing these services are doing this as a business,” says Dr. David Keefe, chair of obstetrics and gynecology at New York University Langone Medical Center. “Generally in science, we like people who are more disinterested to be doing the clinical studies.”

Tilly counters those doubts with evidence from other species showing that these cells can do what OvaScience says they can. Egg stem cells extracted from the ovarian tissue of rats, mice, monkeys, pigs and cows, as well as from women, have developed into immature eggs–and in the case of mice and rats, those eggs have developed and produced viable offspring.

“Eggs get tired as women get older, and the tired egg doesn’t perform as well in creating an embryo,” Tilly says. “Mitochondria from egg precursors rejuvenate the egg to bring it back to a high-quality state.”

That certainly appears to be the case with the Rajanis, and in the coming months, OvaScience will be able to tell whether that’s the case with a host of other women too. “I kept telling myself one day we’d have a child, that hopefully in the end we would get pregnant,” says Natasha. “And we did.”

More Must-Reads from TIME

- Donald Trump Is TIME's 2024 Person of the Year

- Why We Chose Trump as Person of the Year

- Is Intermittent Fasting Good or Bad for You?

- The 100 Must-Read Books of 2024

- The 20 Best Christmas TV Episodes

- Column: If Optimism Feels Ridiculous Now, Try Hope

- The Future of Climate Action Is Trade Policy

- Merle Bombardieri Is Helping People Make the Baby Decision

Contact us at letters@time.com