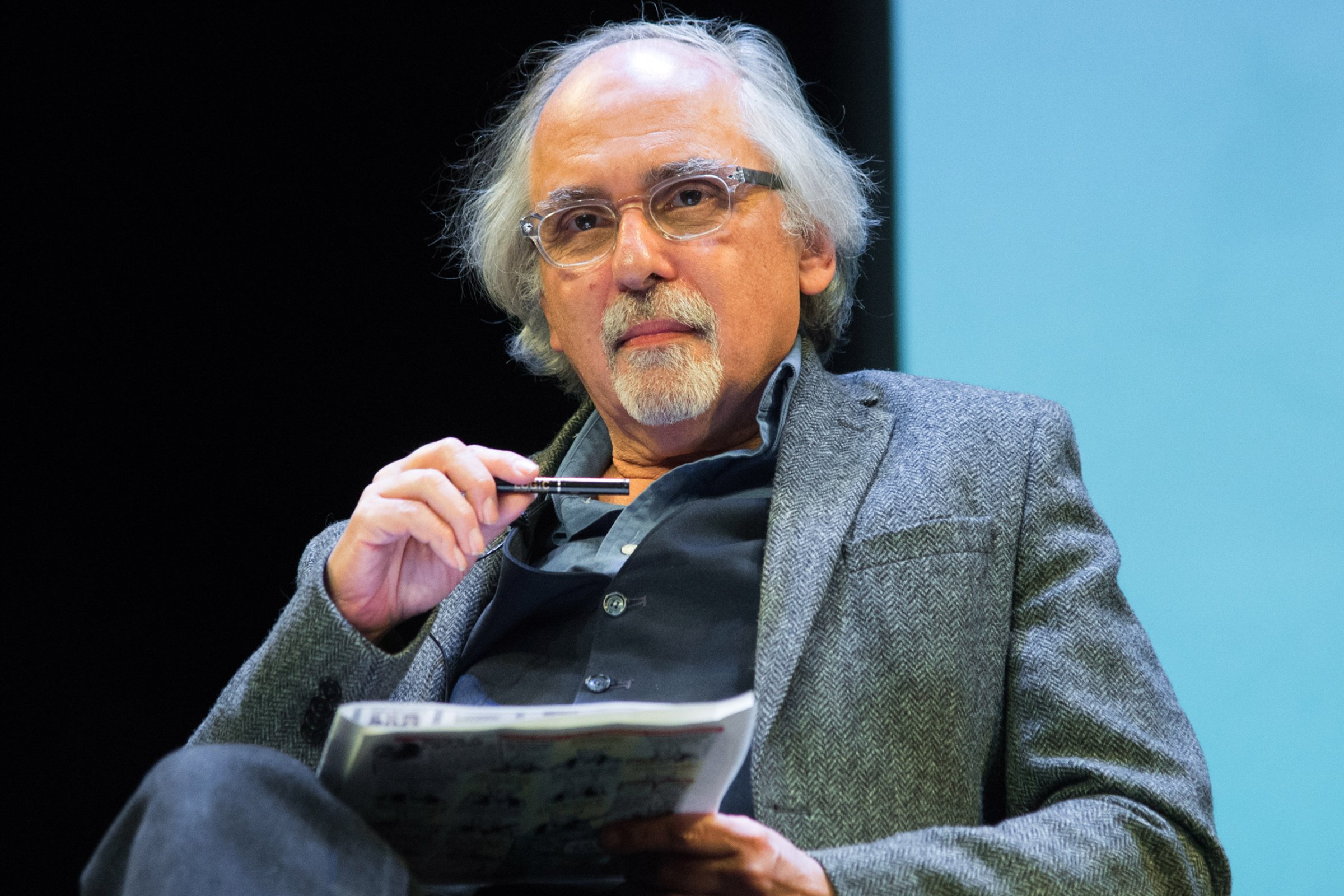

Art Spiegelman is a cartoonist, editor, and the author of Maus.

TIME: After six writers withdrew from hosting last night’s PEN gala honoring Charlie Hebdo, why did you decide to step up and co-host the event?

Spiegelman: It seemed necessary as a corrective to what I saw as boneheaded reasons for the pullout. I decided to accept an invitation to host a table that I’d passed on before, because black tie galas aren’t my thing, and I had something else I was supposed to do that night. But after those six authors, who I’ve come to think of as a kind of super hero team called the Sanctimonious Six, pulled out, I just felt that it was necessary to be a corrective and invite other sympathetic people to be there to shout, “Cartoonist lives matter.”

Why was it important to honor Charlie Hebdo with the James C. Goodale Freedom of Expression Courage Award?

One point that was made over and over again was that this is an award for courage. And it’s hard to be more courageous than going back to work after your office has been bombed and your comrades have been slaughtered. On those grounds alone, one would think, “It’s a no brainer. They get the award.”

Beyond that, the magazine was getting a really bum rap. It’s actually anything but a racist magazine. One of the most touching things for me during the award ceremony last night was having the head of SOS Racisme, a French organization that combats racist activity, very movingly talk about Charlie Hebdo being a great force against racism in France.

They received the award for using their particular vocabulary and medium to stir debate on issues, not to create mischief, and they did it estimably, even when people didn’t agree with them. As one of the editors pointed out yesterday, the Charlie Hebdo editors don’t even agree with each other. The point of these cartoons is to start conversations about these issues. And these issues are not trivial.

This week, we also saw a shooting in Texas outside of a “Draw Muhammad” contest sponsored by the American Freedom Defense Initiative. What’s the difference between Charlie Hebdo and Pamela Geller’s organization?

I think that’s when my brain short-circuited. Because superficially, it seems like, well, the same thing is happening in Texas. But it’s not. It’s the anti-matter, Bizarro World, flipside, mirror-logic version of what Charlie Hebdo is about.

The American Freedom Defense Initiative is racist organization. It’s exactly the nightmare version that the writers who were protesting the PEN award thought Charlie was. But Charlie is an anti-racist, political magazine that does not have an agenda that consists of wanting to bait or trouble Muslims.

Pam Geller’s organization is intentionally trying to start war of culture with Islam by saying that all Muslims are terrorists under the surface, and we’re going to prove it. Do the group members deserve free speech protection? Of course. But they’re hiding behind that banner with things that have very little to do with free speech and a lot to do with race hate.

Je suis Charlie, mais je ne suis pas Pam Geller. She and her dim-witted, ugly organization deserve the protection of the free speech mantle that they wrap themselves in. But would I ever give them a courage award? Hardly. Would I ever want to be in the same room with them? No. Do I wish they would stop? Yes.

The PEN writers who protested the event were projecting similar motives and attitudes onto Charlie Hebdo. Dismissing it as French arrogance is quite arrogant. Dismissing it as crude and vulgar is something that makes me suspicious of how cartoons are viewed by the writers who didn’t have enough respect for these images to understand them on their own.

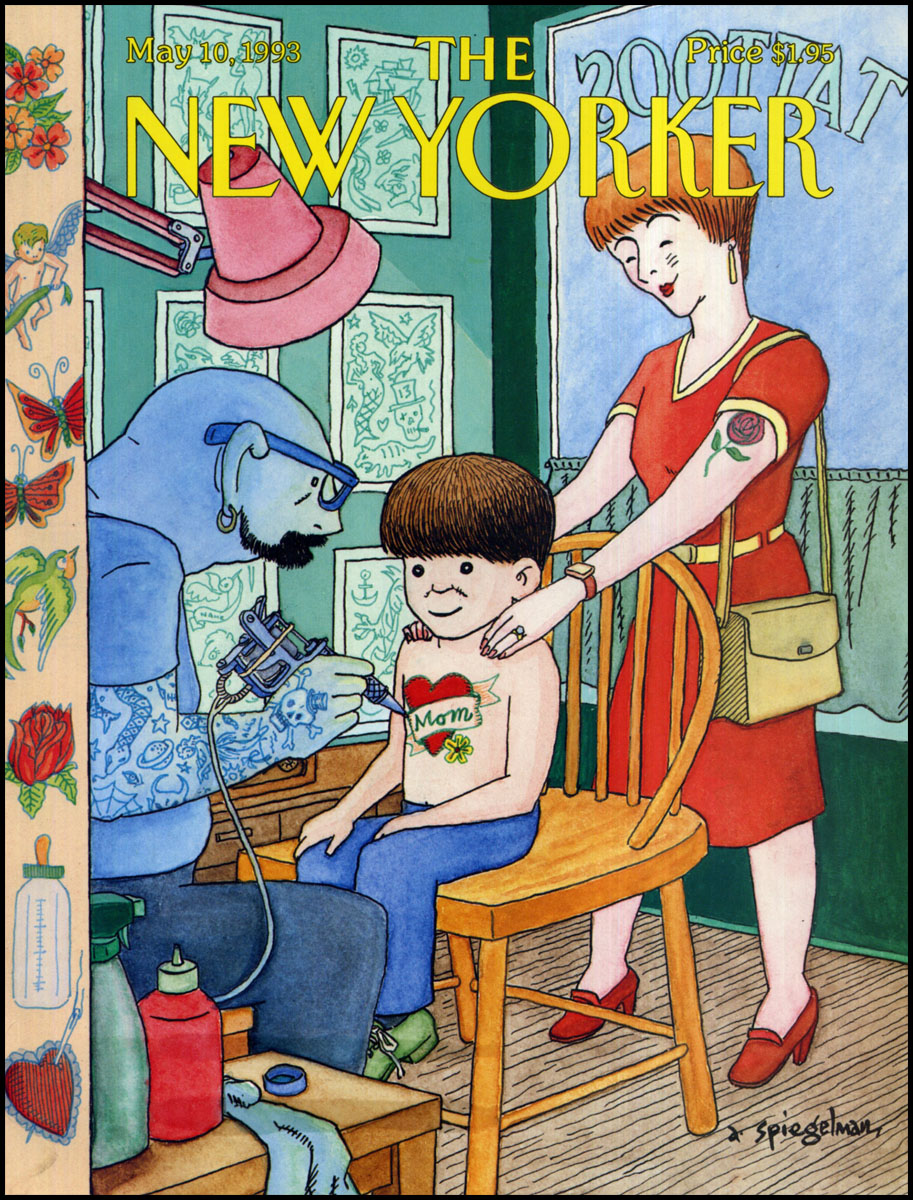

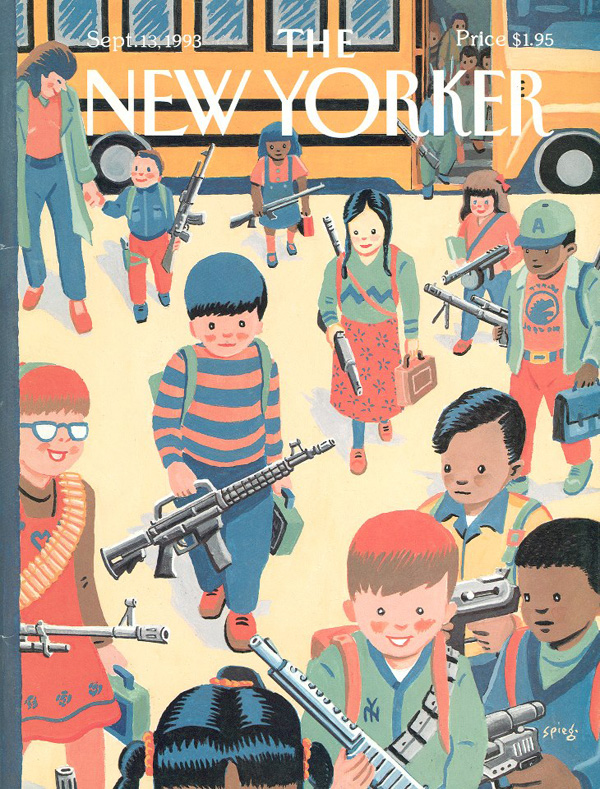

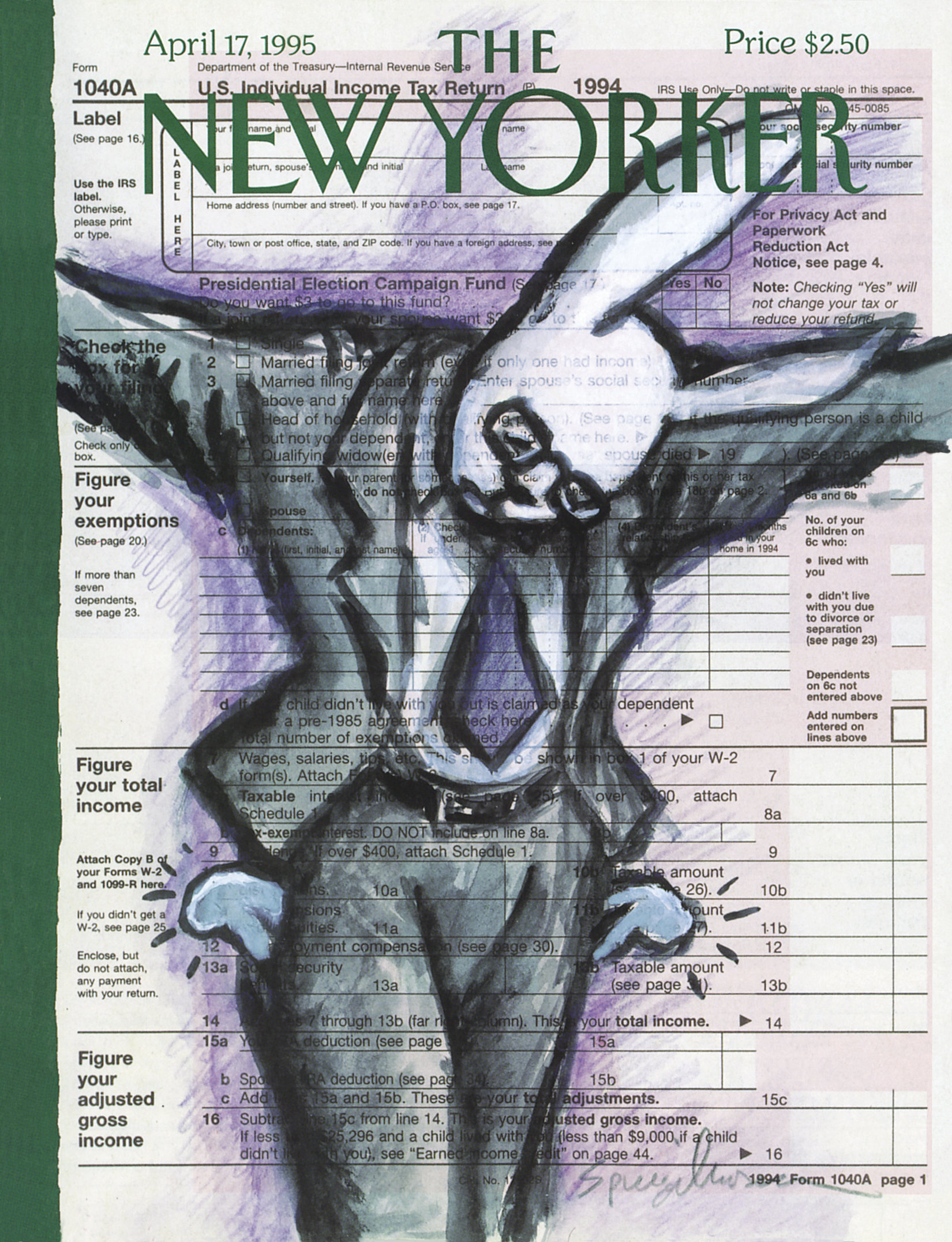

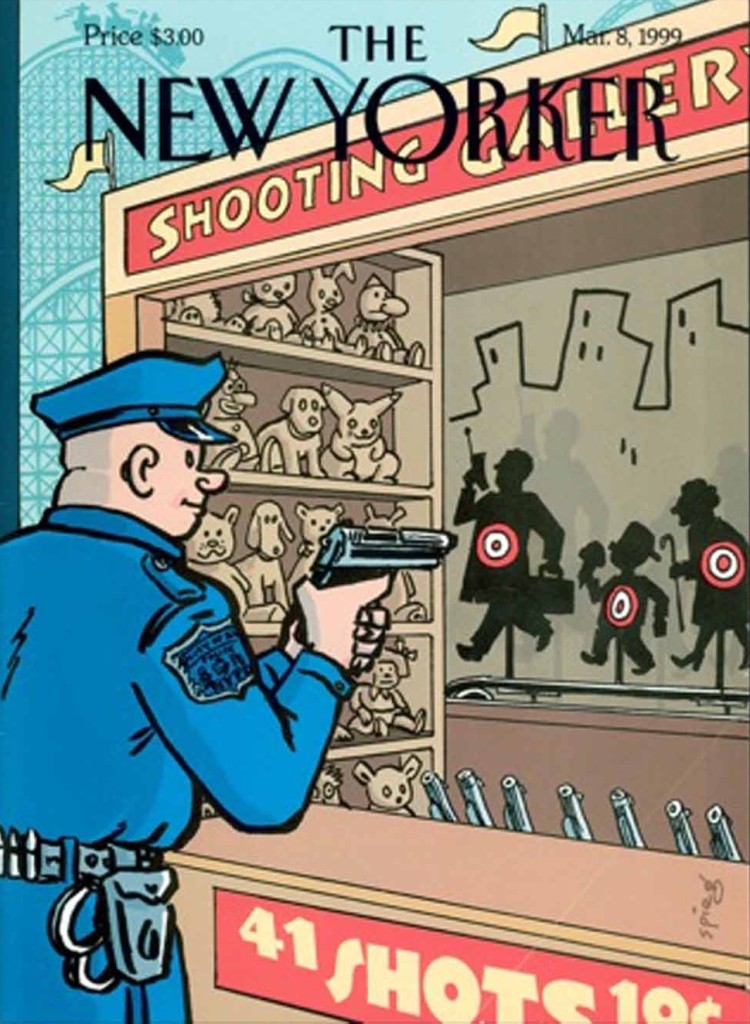

See 10 of Art Spiegelman's Best Social Commentary Cartoons

What is the role of images and cartoons in this debate?

It’s interesting to me that cartoons have been so central to it. Cartoons are so much more immediate than prose. They have a visceral power that doesn’t require you to slow down, but it does require you to slow down if you want to understand them.

They have a deceptive directness that writers can only envy. They deploy the same tools that writers often use: symbolism, irony, metaphor. Cartoons enter your eye in a blink, and can’t be unseen after they’re seen. But to understand some of these cartoons requires a lot of culture immersion and symbol reading and a lot of analysis.

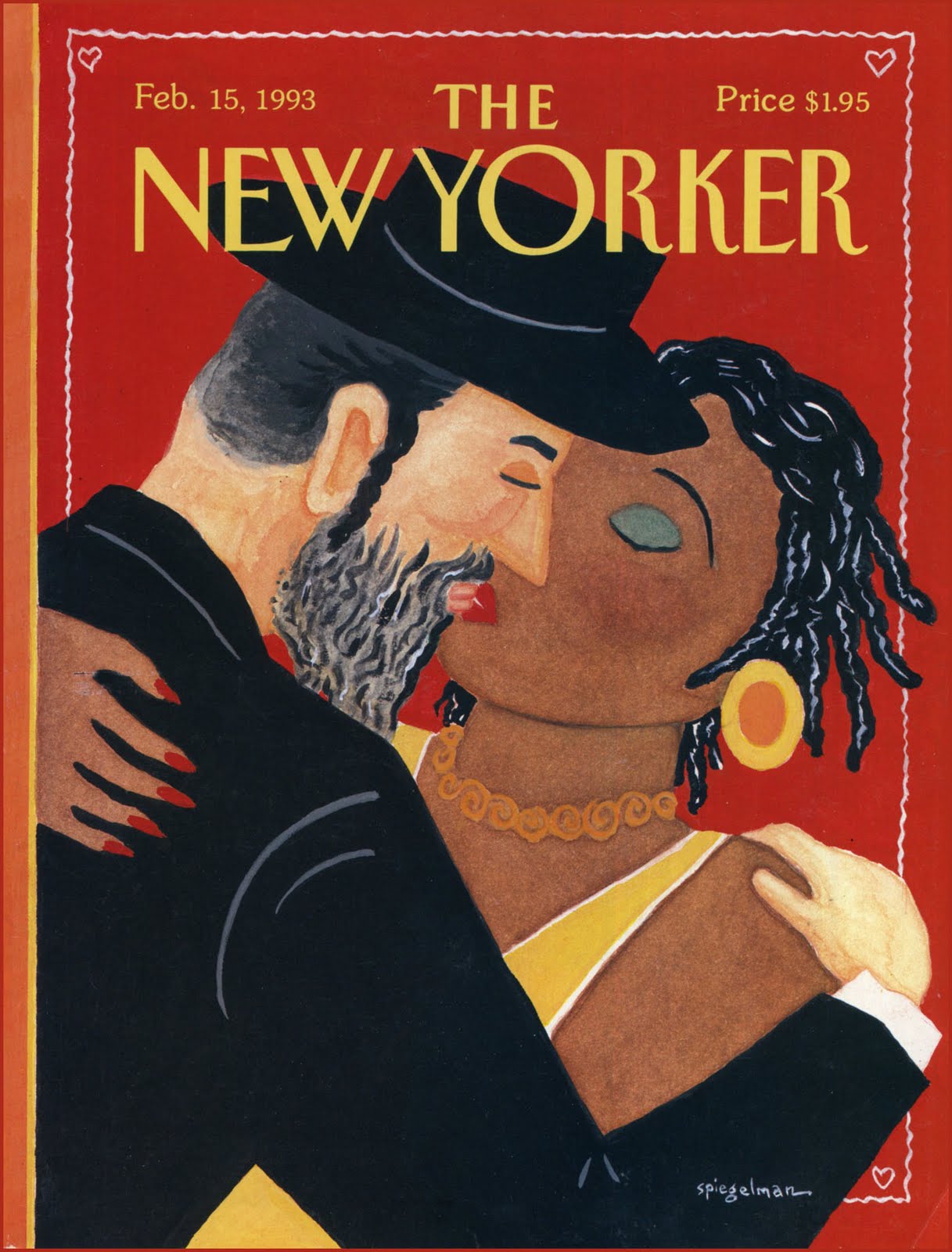

There was a New Yorker cover back in the beginning of my time at the magazine that helped change the magazine’s DNA enough to embrace controversial images. It was in the wake of the Crown Heights race riots in which the West Indian black community and the Hasidic Jew community came to bloody blows. As I was doodling I wondered, “What would the guy with the monocle look like if he were Hasidic?” And then I had a black woman kiss him.

When the cover came out, it created a riot of its own—as much indignation on both sides as possible in the world before the Internet. Among the letters that came in to the magazine was a letter from a young woman saying that she thought it was really sweet that on Abe Lincoln’s birthday there was a picture of Lincoln kissing a slave. What’s so amazing about that is that it gets right to the heart of the problem that some of the protesting PEN writers have: learning to read images. They’re very easy to misread without enough information, and some of my writing brethren are great mis-readers.

What would you like to see moving forward?

We should be teaching visual literacy in all schools. We’re bombarded with images more and more, and we have less and less time to understand them. What’s amazing about these simple drawings is that they stand still long enough for you to circle them and get around them in ways you often can’t with videos.

It’s not easy for Americans, because for one thing there are hardly any political cartoonists in America at this point. Political cartoonists are a dying breed. Here there are fewer newspapers, fewer newspapers with a cartoonist on staff, and political cartoons have been reduced to being a variant of a gag cartoon because the last thing a newspaper would want to do is lose a single reader.

I’m stuck having to agree with my bête noir friend Pam Geller that it would be better going forward for newspapers and magazines to take on the responsibility for showing these images. When the Danish Muhammad cartoons appeared in 2006, and when the Mohammad cartoons from Charlie Hebdo appeared, newspapers should have shown these images and talked about them. Many dismissed them as banal and treated them as, “Nothing to see here, move along.”

If it were taken as a matter of course for newspapers and magazines to show these images, they could be normalized, so the many Muslims not offended to the point of grabbing a machine gun could understand that this is how our culture functions with images and issues. It would create a better-informed population dealing with whatever comes next. It would also be useful to have other voices on newspaper and magazine staffs.

What’s the mistake in not publishing images that could be deemed offensive?

There’s no stopping it. What would it be based on? Would it be based on when someone takes up arms against the image? Would it be based on when someone thinks it’s offensive? God knows where the line would be drawn. It can’t be drawn that way. There is an incredible efficiency cartoons have, once you learn to read them, in clarifying the issues at hand, making them memorable.

There’s something basic about cartoons. They work they way the brain works. We think in small, iconic images. An infant can recognize a smiley face before it can recognize its mother’s smile. We think in little bursts of language. This is how cartoons are structured. They’re structured to talk to something deep inside our brains. A cartoon becomes a new kind of word that didn’t exist before.

It’s interesting how little respect they get. “Oh, anyone could draw that crude, vulgar scrawl,” said a number of critics of Charlie Hedbo. That’s not quite true. They’re not totally dismissible. If a writer had made some of the points that Charlie Hebdo had made, I don’t think the writers protesting PEN would have been so condescending and dismissive.

More Must-Reads from TIME

- Cybersecurity Experts Are Sounding the Alarm on DOGE

- Meet the 2025 Women of the Year

- The Harsh Truth About Disability Inclusion

- Why Do More Young Adults Have Cancer?

- Colman Domingo Leads With Radical Love

- How to Get Better at Doing Things Alone

- Michelle Zauner Stares Down the Darkness

Contact us at letters@time.com