Contains minor spoilers for the fifth episode of Game of Thrones Season 5

The region once seemed wealthy and relatively peaceful, but that façade of prosperity was built on the backs of slaves. Those who traded in human lives, though vastly outnumbered, held the power and wealth. Though custom and courtliness were valued within the walls of their grand homes, the masters ruled ruthlessly, with sexual and economic exploitation.

Then came an outsider whose mandate they questioned, but whose armies were strong and whose moral code was even stronger. When the fighting stopped, the slaves were free, the economic system was upended, the outsider’s right to rule was no longer up for debate.

And yet it would soon become clear that declaring an end to slavery was only the first step: some of those who had lost power returned as masked vigilantes, determined to put an end to equality, and those who had gained power struggled with how to use it. The well-intentioned leader, bombarded with conflicting advice, searched for the best way forward.

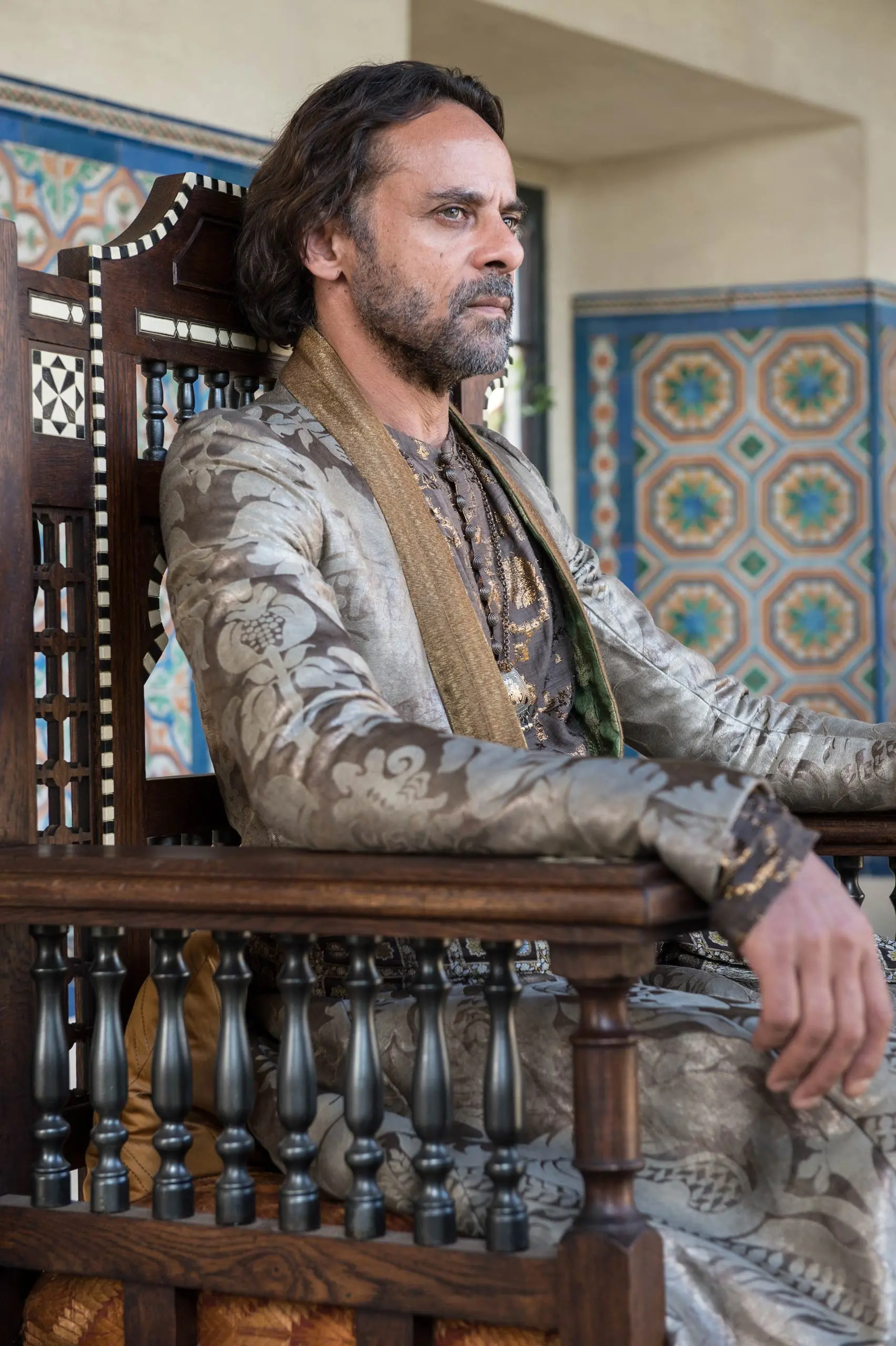

Fans of Game of Thrones will recognize that story as the saga of Slaver’s Bay, where Daenerys, the Khaleesi and Mother of Dragons, rules the unstable former slaving city of Meereen. As it was phrased in the episode that aired May 10, “Though Daenerys maintains her grip on Slaver’s Bay, forces rise against her from within and without. She refuses to leave until the freedom of the former slaves is secure.”

Those more attuned to real history than to fantasy may recognize a very different place: the United States in the years following the Civil War.

The historical period generally referred to as Reconstruction began around 1865 as President Lincoln and his allies confronted the question of what to do with the South after its rebellion ended. Lincoln had said in his second Inaugural address that there would be “malice toward none” when peace arrived, but that would be a difficult pledge to keep. How much revenge would the North exact? What would happen to those who had been slaves? How could the Southern states rejoin the Union, and which part of the government would oversee that process?

The solution that Lincoln devised involved requiring 10% of voters in each of the rebel states to swear an oath of allegiance to the Union, after which the states would be eligible to hold elections and generally not be considered in rebellion anymore. Some people in his own party (the Radical Reconstructionists) wanted more demands placed on the South; some people (like Vice President Andrew Johnson, who became president after Lincoln was assassinated in 1865) wanted fewer.

After Lincoln was dead the Radical Reconstructionists defied Johnson in order to pass the 14th and 15th Amendments, and to establish Republican-controlled governments within the Southern states. African Americans, newly freed, were elected to office, and they worked to improve the educational and social prospects of former slaves.

However, the era now known as Redemption would set back that progress. A financial panic in 1873 and political maneuvering in the 1876 election came to occupy minds in the north, as Southern white Democrats returned to power and began to institute discriminatory laws. Many former slaves became sharecroppers, still bound to the wealthy but through contracts rather than ownership. The Ku Klux Klan was founded during this period, turning fear of change into a violent force for oppression.

The social systems put in place during the Southern Redemption would shape the next century of life in America, with the black codes and Jim Crow laws that were created to get around the law of Reconstruction enduring until the 1960s. The effects of that codified discrimination are still being felt today.

So what does all of this have to do with Game of Thrones?

Daenerys is currently in the Reconstruction phase of her conquest. Like Lincoln, she is only able to bring freedom through military action. Her decision to remain in Meereen and rule, rather than delegating the way she did in Yunkai and Astapor, is like the Radical Reconstructionists’ desire to keep Republican politicians in power in the South; she has seen how those other cities were either destroyed or “redeemed” with the return of the Wise Masters to their old ways.

The Sons of the Harpy, like the KKK, use terror to lash out at those who upset their power structure. Khaleesi’s decision to allow Freedmen to contract their labor—and the argument about reopening the Fighting Pits—calls to mind the economic fate that faced many slaves freed in real life. The arguments among her advisers about how best to deal with a conquered people played out in Congress. She faces the familiar questions of how to balance vengeance via dragon and unity via marriage. (Some Game of Thrones watchers earlier saw a racial parallel as well, in noticing that the oppressed residents of Slaver’s Bay are all darker than Daenerys is).

Game of Thrones is a work of fiction, of course; the cruelty of real slavery cannot be compared to a fantastical depiction. But it believably portrays the dangerous obstacles that exist in the wake of such cruelty. Author George R.R. Martin is conscious of history, and his study of the perils and perks of power is grounded in the way things really work. The show has been praised for its realistic psychology, and here’s proof that such realism isn’t limited to the interpersonal relationships it highlights.

Nobody except the show’s creators knows what Martin, currently working on a sixth volume in the epic series, has planned for Daenerys — and the show is about to get ahead of the books, anyway. But the lessons of history suggest it won’t be an easy road.

See Photos from Game of Thrones Season 5

More Must-Reads from TIME

- Donald Trump Is TIME's 2024 Person of the Year

- Why We Chose Trump as Person of the Year

- Is Intermittent Fasting Good or Bad for You?

- The 100 Must-Read Books of 2024

- The 20 Best Christmas TV Episodes

- Column: If Optimism Feels Ridiculous Now, Try Hope

- The Future of Climate Action Is Trade Policy

- Merle Bombardieri Is Helping People Make the Baby Decision

Write to Lily Rothman at lily.rothman@time.com