Thursday night, PEN, an organization of writers devoted to freedom of expression, gave an award to the French magazine Charlie Hebdo. It’s the sort of ceremony, taking place at a New York gala attended by the literary world’s upper crust, that would seem de rigeur—PEN events in recent years haven’t drawn much attention, or elicited much conversation, outside of the narrow world of writers and editors. But the award to Charlie Hebdo, and the debate over whether or not it was merited, has resonances beyond literary circles. It gets to the heart of how America is meant to respond, in the long-term, to the terrorist attack on the magazine.

Earlier this year, the offices of the magazine in Paris were attacked, part of a string of violent responses to the publication of depictions of Mohammed, which are forbidden in the Muslim faith. This gave rise to two things: first the global popularity of the phrase “Je suis Charlie,” in solidarity with the slain magazine staffers, and later, to a debate over exactly what the value of Charlie Hebdo‘s provocation had been. This was a difficult needle to thread: The magazine styled itself as an equal-opportunity provocateur but many felt it had a particular taste for needling France’s Muslim minority.

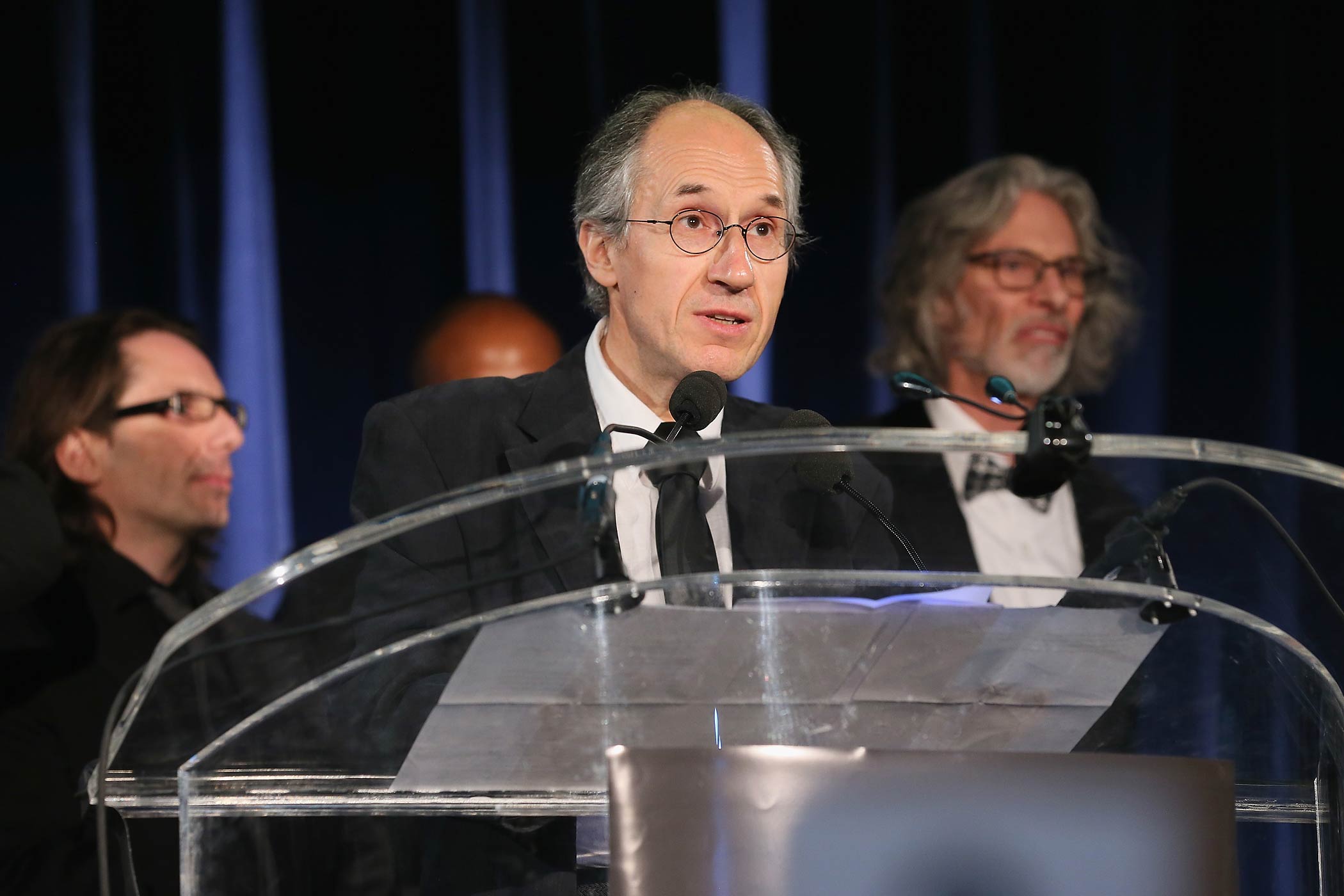

PEN’s decision to honor the magazine didn’t merely condemn the murders or call for solidarity with the magazine’s writers. The decision argued that these men and women were exemplary and deserving of praise and honor. Many critics of the decision (including Junot Díaz, Lorrie Moore, and Joyce Carol Oates) signed an open letter to PEN that argued an award given to the Charlie Hebdo staff was a different thing from decrying their murder, and that, while the events in Paris were to be decried, other recipients may have been more deserving of an award for furthering the cause of free expression. Couched though this was in sympathy for loss of life, it still occasioned impassioned defenses of the magazine from many, including Salman Rushdie. The knee-jerk defense of Charlie Hebdo, that we were all Charlie, became something much more complicated, given the number of people who felt empowered to say that they didn’t want to be Charlie. The award finally broke through a set of received opinions around Charlie Hebdo that were unsustainable.

Even still, this award, in the grand scheme of human events and even for the New York-based literary community, means little. But the opportunity it provided to further the conversation about speech means a lot. What sorts of speech are worth defending is, for most believers in free expression, obvious—it’s all of them! But what sorts of speech are worth valorizing is a much more complicated matter—one that had been difficult to confront in a flurry of earnest sympathy for slain writers. There are very few free-speech cases in which the sort of speech is, to so many, as offensive as that of Charlie Hebdo. That makes the questions thornier, and more worthwhile.

The debate is far from over, and it shouldn’t be restricted to the New York literary community—though writers, concerned as they are with words and expression, are the vanguard on this. The recent shootings at a Texas “Prophet Mohammed cartoon contest” show that the Charlie sensibility, and the terrifying reaction it can elicit, is still with us. Do those who stood with Charlie stand, now, with the self-consciously provocative prophet artists in Texas? Those who do, and those who do not, should have the same sort of debate that’s been unfolding in New York. It would be a far better tribute to free speech than signing on to a catchphrase and a set of pieties.

More Must-Reads from TIME

- Donald Trump Is TIME's 2024 Person of the Year

- Why We Chose Trump as Person of the Year

- Is Intermittent Fasting Good or Bad for You?

- The 100 Must-Read Books of 2024

- The 20 Best Christmas TV Episodes

- Column: If Optimism Feels Ridiculous Now, Try Hope

- The Future of Climate Action Is Trade Policy

- Merle Bombardieri Is Helping People Make the Baby Decision

Contact us at letters@time.com