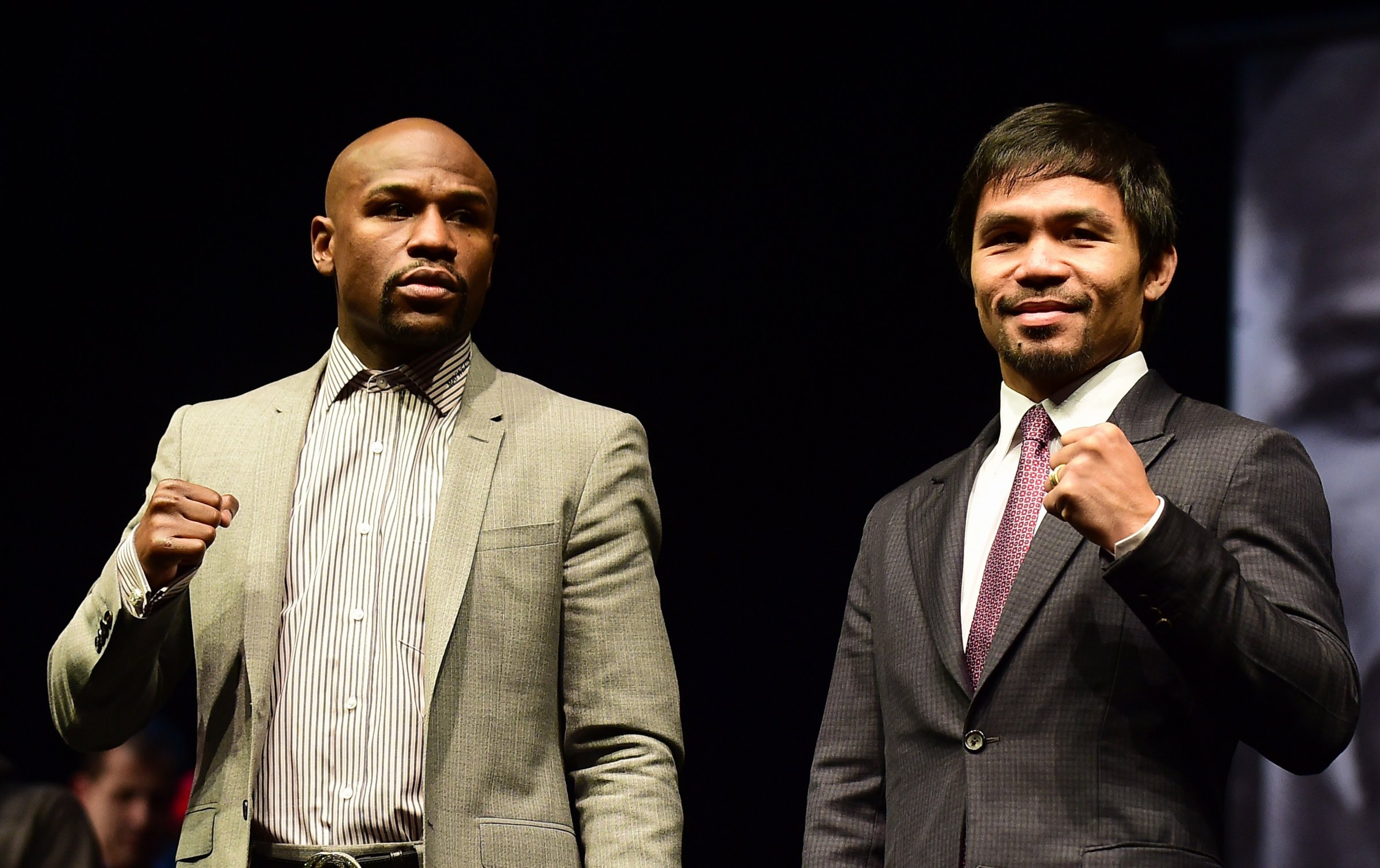

A neighbor invited me to watch the Floyd Mayweather-Manny Pacquiao fight and I said, “I’d rather spend the time shooting birds or teaching my Cocker Spaniel to kill Yorkies.” That was almost true even though Saturday night’s bout has been hyped as the biggest since the one that changed my life.

In 1964, when Cassius Clay challenged Sonny Liston for his world heavyweight title, the New York Times boxing writer didn’t think the fight was worthy enough – or would last long enough – to justify his presence. Clay was a blood sacrifice to the box office. Liston was a 7-1 favorite. Why not send that kid on night rewrite?

Clay won and became Muhammad Ali. I became the boxing writer and began to dislike boxing. I couldn’t figure out what this so-called sport was about, this romanticized “sweet science,” beyond slaking the blood lust of slumming gentry and offering poor boys the chance for paydays before their brains crumbled. I liked the boxers – I loved Ali, which was easy – because they were mostly brave and big-hearted and unlike the thuggish baseball players I also covered, they weren’t hostile to questions. Before big fights, I’d spend days in training camp with both opponents. By the opening bell I didn’t want either of them to get hurt. They often did and sometimes died.

Ali made us think this wasn’t about beating on people for money, it was history or comparative religion or performance art. But to see him stumble through his later fights or just try to walk now, it’s clear that it has always been about hitting and getting hit to arouse a paying crowd. What’s wrong with us? Not enough brain trauma from football and improvised explosive devices?

Keith Olbermann at ESPN has called for a boycott of the fight because of Floyd “Money” Mayweather’s record of five convictions for violence against four different women. This seems appropriate but narrow. What about violence period? What justification is there for beating on anyone? Even for money. Mugging is a survival activity, too.

Howard Cosell, after years as a premier boxing broadcaster, abandoned the sport in 1982. Entranced by the fighters, as was I, he was finally disgusted by a mismatch which could have led to another serious injury. He was reviled as a hypocrite by sportswriters still feeding at the sordid trough.

The cradle of American boxing was the slave plantation, where black men fought for their owners, who bet on them, as they did on their horses and dogs. Sometimes, a slave earned his freedom from the ring; some went to England and taught pugilism in gentlemen’s clubs. The descendants of those who stayed sometimes got to fight in “battle royals,” groups of blind-folded black youths pummeling each other at “smokers” for white men.

The history of boxing never got much better. It flourished even when illegal, in underground clubs and on river barges. It has been the least regulated of sports, no federal oversight, unions or benefits. Most boxing commissions are appointed by politicians and under pressure from local businesses. I’ve always found the promotors among the most unsavory figures in sports; lazy writers found them “raffish.” The drama of impending tragedy made boxing the easiest of sports to write about; it also served me well in three novels.

And here we are again, about to see fortunes made on the anticipation of blood and damage. There is a narrative to make it seem as though more is going on, this ex-con woman beater against a mellow politician, evil versus good if you want to make that leap. That’s so much lipstick on a pig’s snout. It’s all about two people trying to disable each other for money because it gives you a thrill. I’m staying home and you should, too.

More Must-Reads from TIME

- Inside Elon Musk’s War on Washington

- Introducing the 2025 Closers

- Colman Domingo Leads With Radical Love

- Why, Exactly, Is Alcohol So Bad for You?

- The Motivational Trick That Makes You Exercise Harder

- 11 New Books to Read in February

- How to Get Better at Doing Things Alone

- Column: Trump’s Trans Military Ban Betrays Our Troops

Contact us at letters@time.com