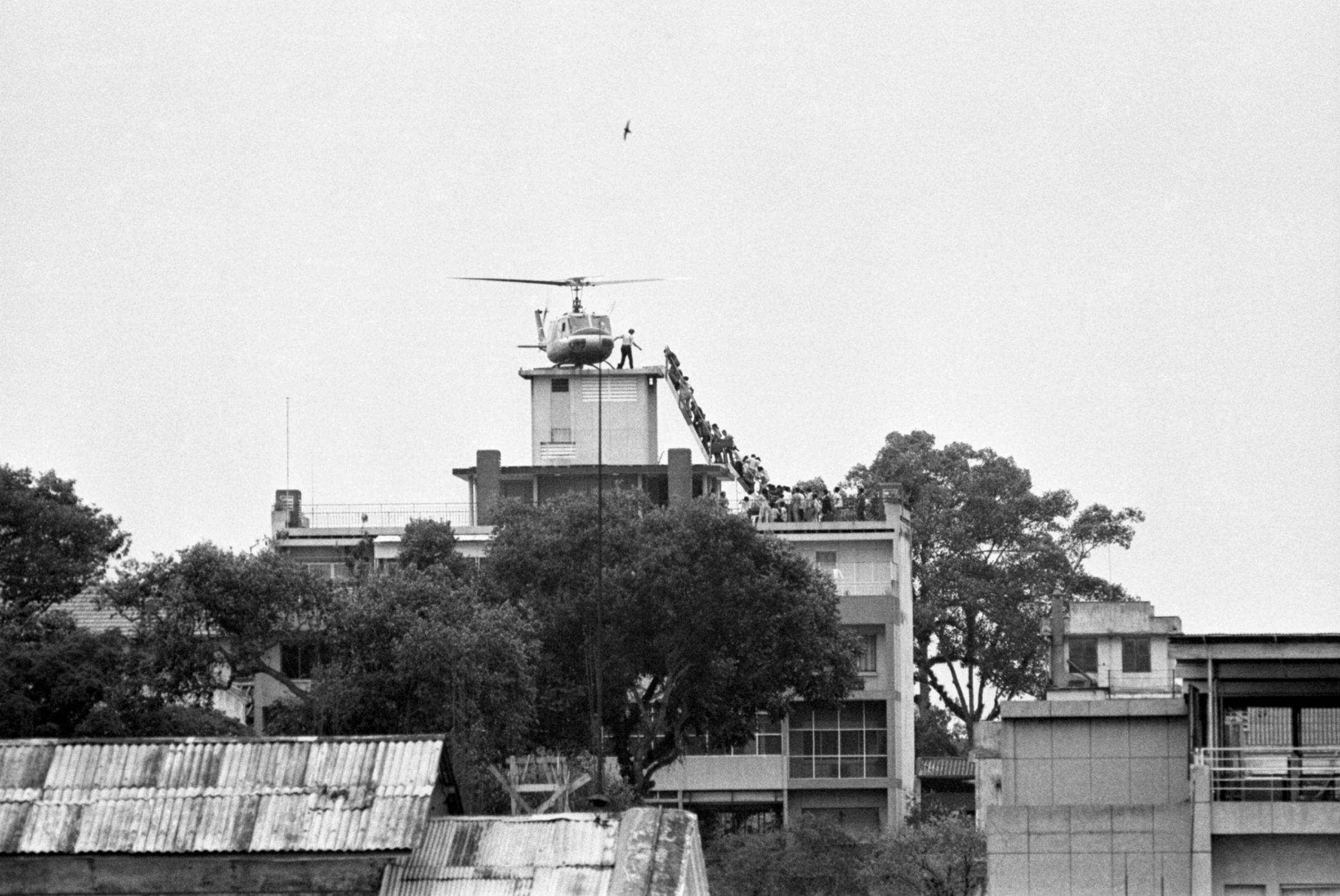

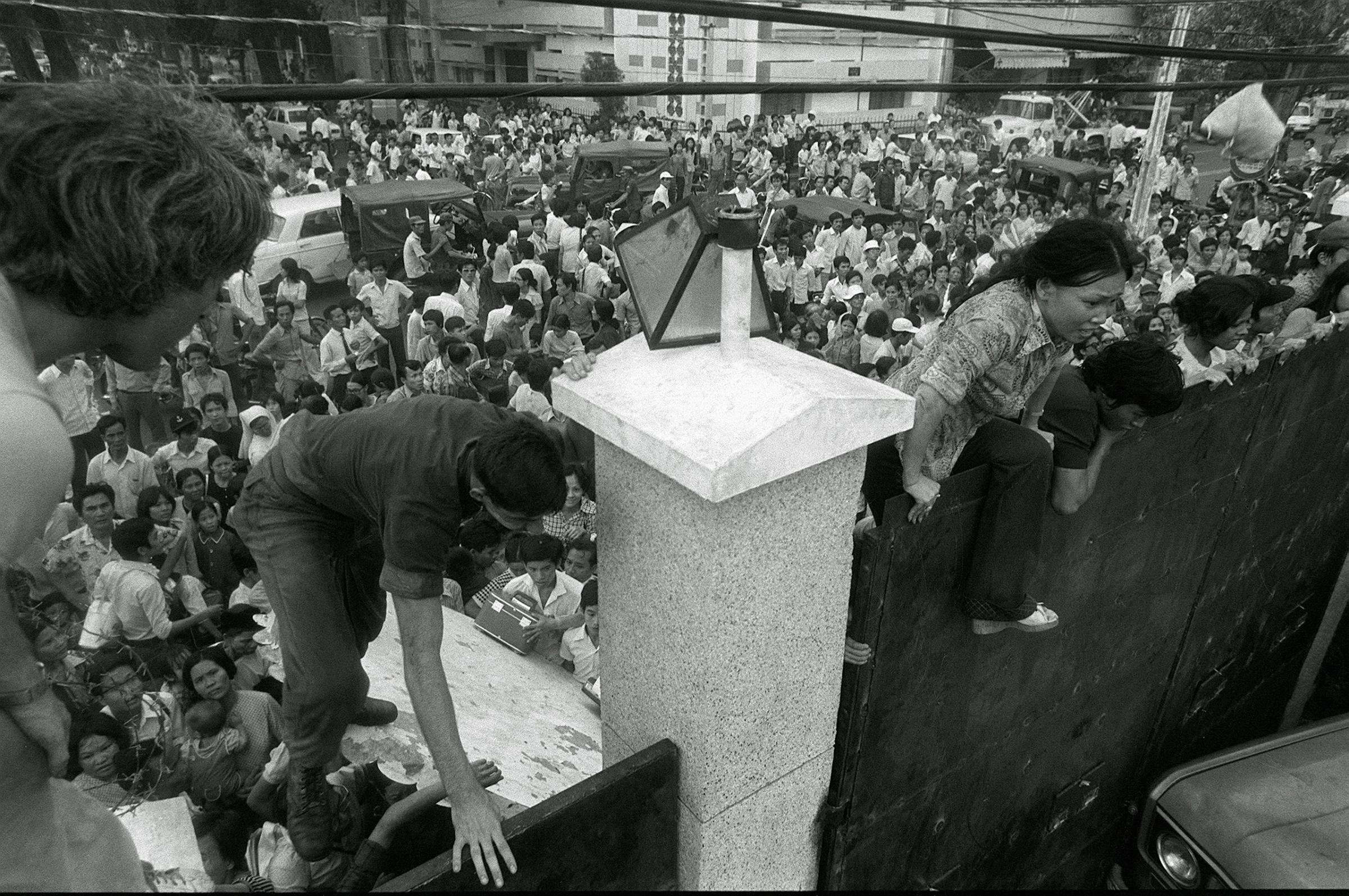

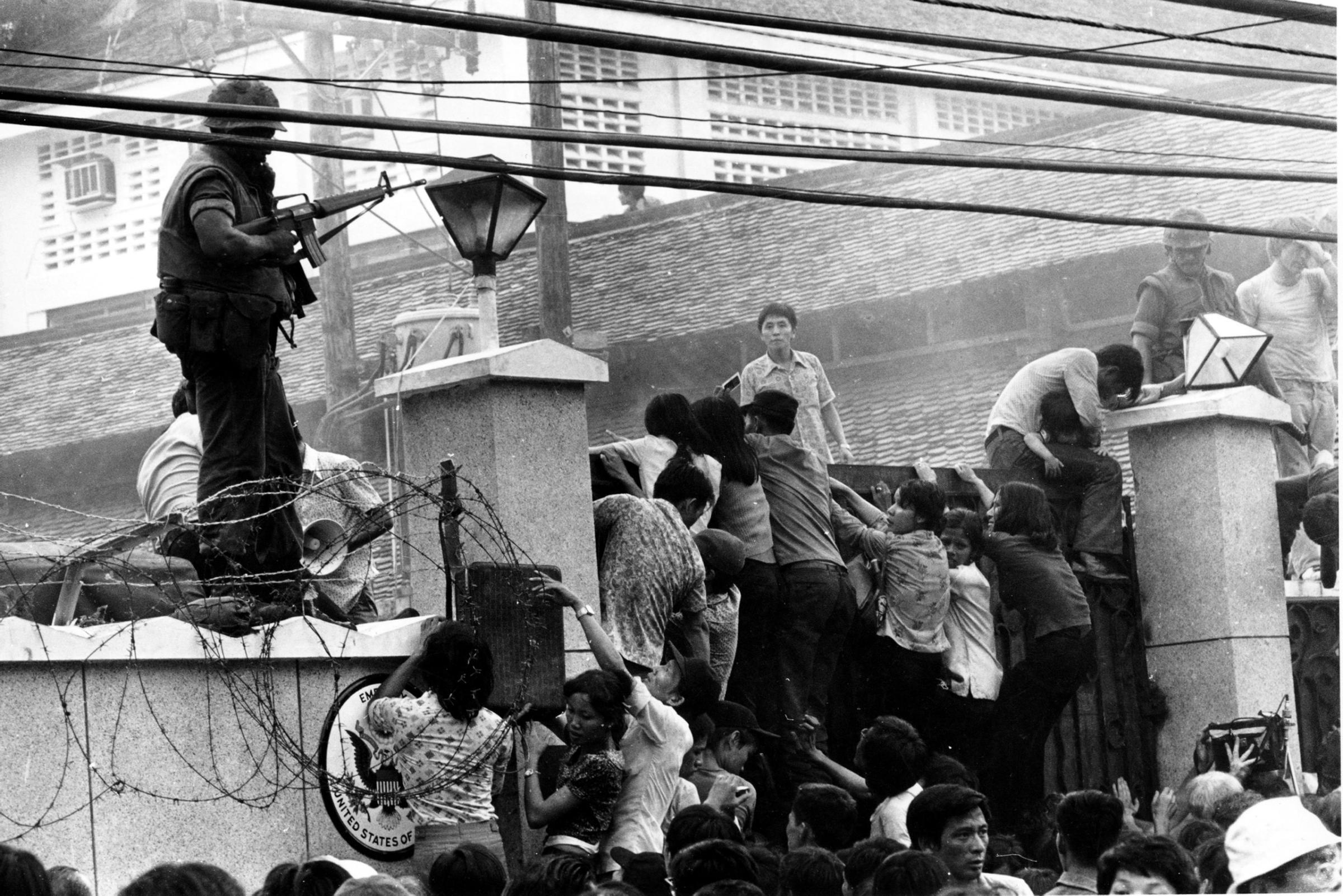

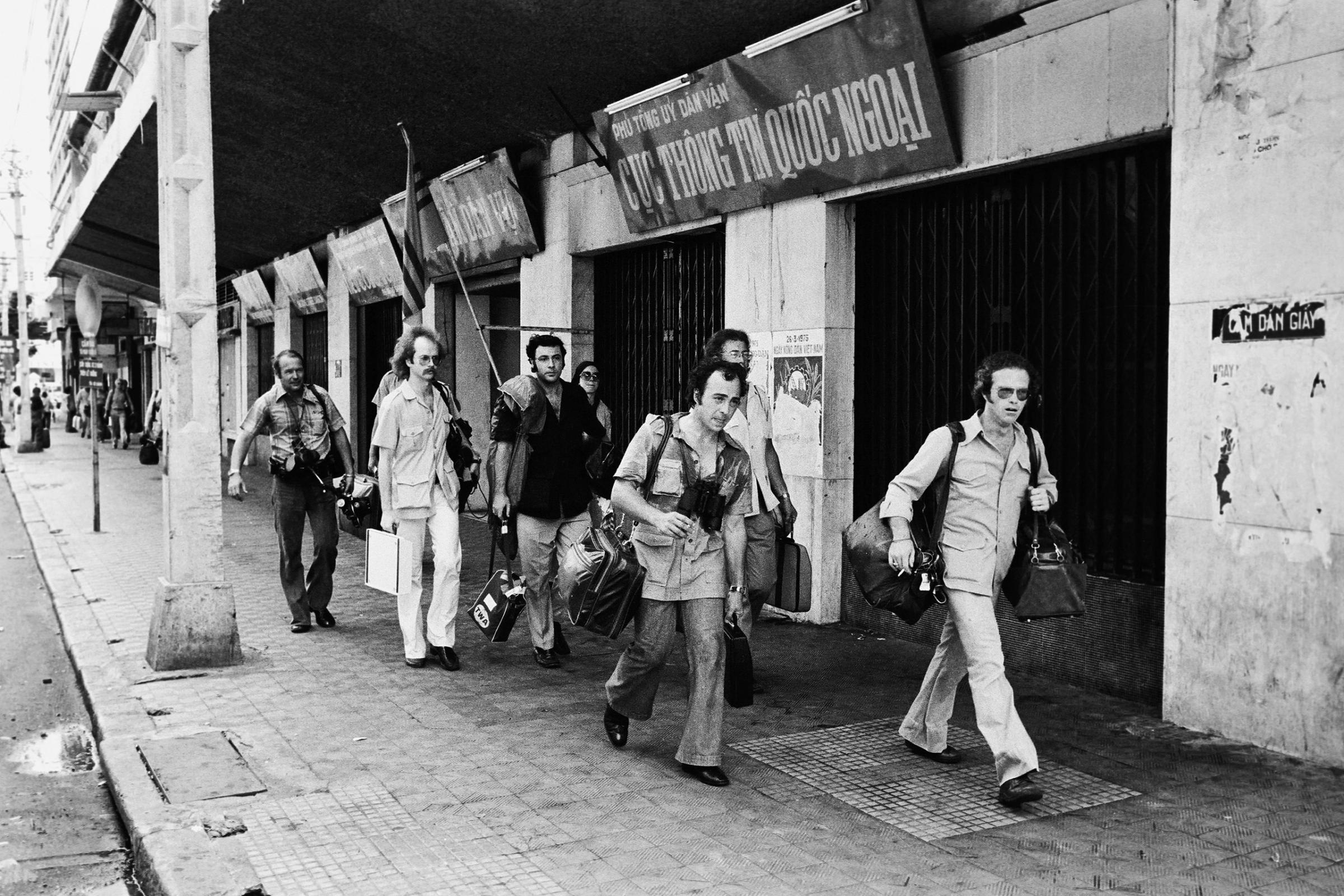

Forty years ago today, on April 30, 1975, helicopters carried away the last Americans in Saigon as North Vietnamese troops entered the city. What followed showed that the war had changed the United States as much as it had changed South Vietnam.

Only 28 months before the end, President Nixon had announced that the war’s end would come with “peace with honor,” and promised to respond vigorously to any North Vietnamese violations of the peace agreement. But Congress had insisted upon a final end to military action in Southeast Asia in the summer of 1973, and Watergate had driven Nixon out of office a year later. Neither the US government nor their South Vietnamese ally, President Thieu, had shown any interest in implementing the provisions of the peace agreement designed to lead to genuine peace The millions of young Americans who had served in South Vietnam from 1962 through 1972, and the thousands of planes that had flown bombing missions from carriers and airfields in the region, had proven time and time again that they could hold on to most of the country as long as they were there. But the Americans could do nothing about the political weakness of the South Vietnamese government. The communists still effectively ruled much of the countryside and had infiltrated every level of the South Vietnamese government from the Presidential palace on down. American money, not loyalty, had driven the South Vietnamese war effort. With no prospect of American help, the South Vietnamese Army simply collapsed in the spring of 1975 after Thieu ordered a precipitous withdrawal from the Central Highlands. The North Vietnamese won their final victory almost without fighting.

A variant of this sad story has already been replayed in Iraq, where tens of thousands of supposedly American-trained Iraqi Army troops melted away in 2014 when faced with ISIS. There, too, the American-backed government had totally failed to secure the allegiance of the population in Sunni areas. The same thing may well happen in Afghanistan, where a new President has already persuaded the Obama Administration to delay a final withdrawal. That was the overwhelming lesson of Vietnam: that American forces, no matter how large, cannot create a strong allied government where the local will is lacking.

Like most historical lessons, that one lasted for as long as men and women who were at least 40 years old in 1975 held power. Army officers like Colin Powell were determined never to see anything similar happen on their watch, and they kept the military out of similar situations in El Salvador and Lebanon during the Reagan years. Instead, the Soviet Union found its own Vietnam in Afghanistan, and that last foreign policy adventure helped bring Communism down. In 1990-1, George H. W. Bush decided to expel Saddam Hussein from Kuwait, but Powell and others made sure that operation would be carried out quickly, with overwhelming force, and with no long-term occupation of enemy territory. Bill Clinton, who had opposed the Vietnam War, kept the United States out of any ground wars as well.

The neoconservatives who took over policy and strategy under George H. W. Bush were either too young to have fought in Vietnam, or, like Bush (and, for that matter, myself), had served in non-combatant roles. Some of them had persuaded themselves that Vietnam would have been successful if the United States had sent South Vietnam more aid, and all of them were certain they could topple the Iraqi government without serious repercussions. Iraq in 2003 was about twice as populated and much larger in area than South Vietnam in 1962, but they were certain that less than a third of the troops eventually needed in South Vietnam would do the job. They were wrong on all counts. Late in Bush’s second term, American troops showed once again that they could quiet an uprising as long as they remained in the country. But the Iraqi government was determined to see them leave, and last year it seemed that that government might go the way of President Thieu. That has not happened, but Baghdad seems to have lost control of much of the Sunni region for a long time to come.

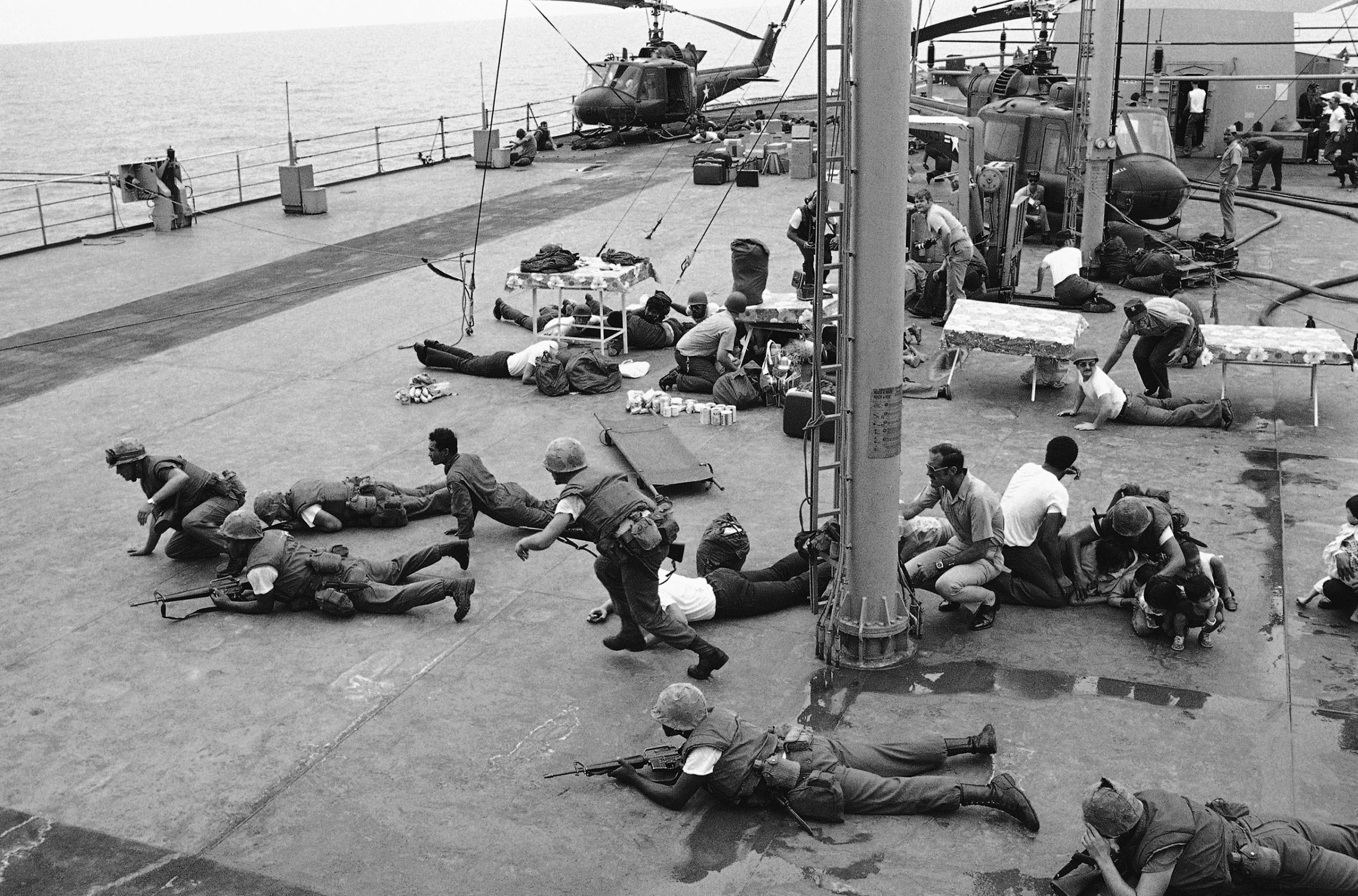

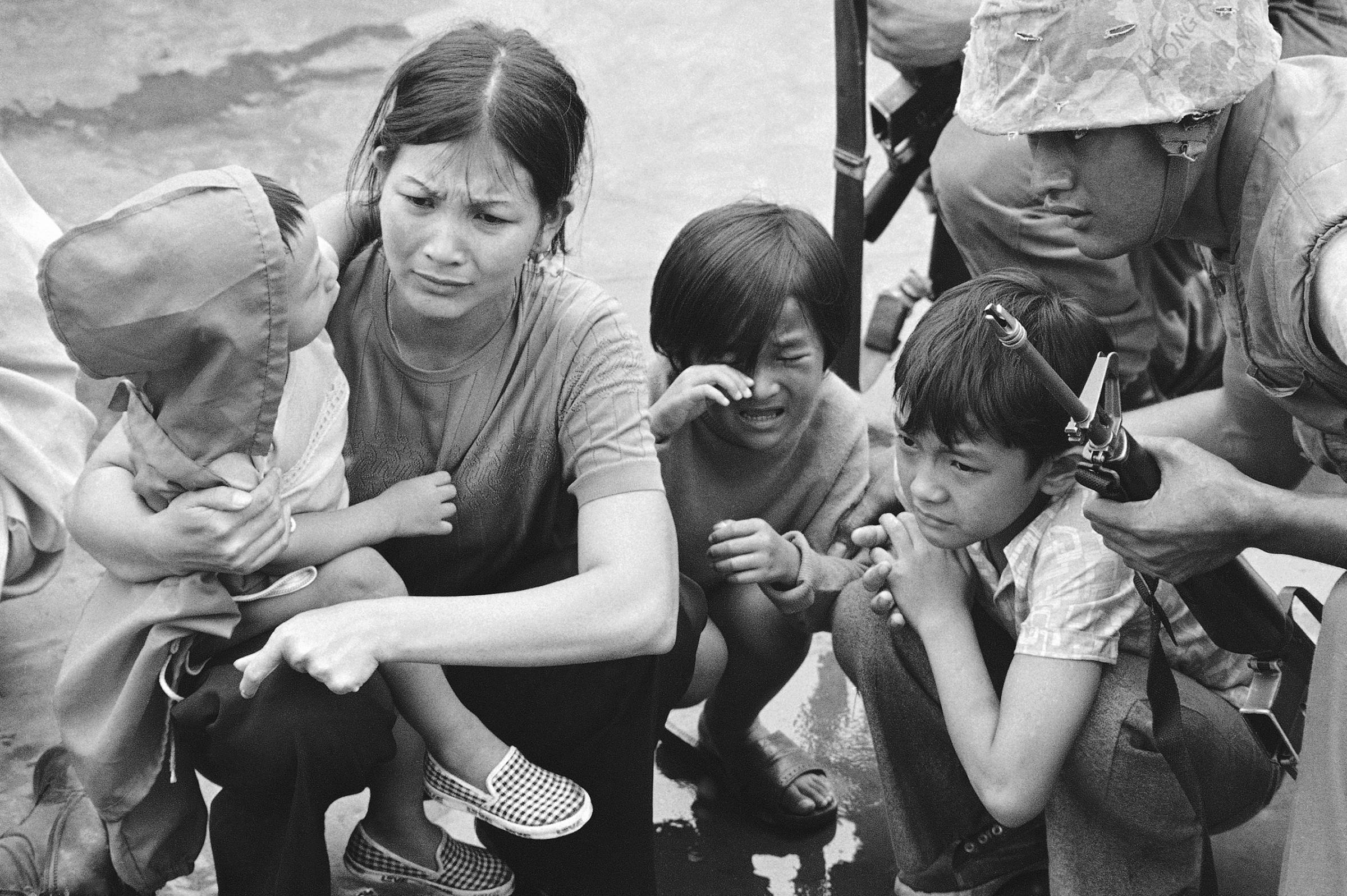

The Last 48 Hours of the Vietnam War in Photos

President Gerald Ford was the American hero of the last phase of the Vietnam War. Although Congress had refused his requests for additional aid to the South in those last desperate weeks, he refused to blame Congress, war protesters, or the media for the fall of Saigon. On April 23, with the complete collapse of South Vietnam only days away, the President gave a major speech in New Orleans. “Today,” he said, “America can regain the sense of pride that existed before Vietnam. But it cannot be achieved by refighting a war that is finished as far as America is concerned. As I see it, the time has come to look forward to an agenda for the future, to unify, to bind up the Nation’s wounds, and to restore its health and its optimistic self-confidence.” This much-underrated President, who was destined to lose a close election in another 18 months, had caught the mood of the American people. Henry Kissinger had explained to Nixon in the fall of 1972 that the US could survive the eventual fall of South Vietnam if the South Vietnamese could clearly be held responsible—immediately began blaming the Soviet Union on the one hand, and the Congress on the other, for the debacle. But Ford gave the American people permission to feel that they had given far more than anyone could ever have expected to this hopeless cause.

It seems today as if another frustrating series of interventions has temporarily vaccinated the US against any such large-scale deployments. Neither politicians nor military leaders will be eager to repeat the Iraq experience for a long time, and the Obama Administration has moved from “counterinsurgency” to “counterterror,” relying on drone strikes. But since the interventions in Iraq and Afghanistan seem likely to lead to endless chaos rather than to the symbolic fall of a capital, it seems unlikely that Obama or any future President will manage to put our Middle East adventure behind us in the way that Ford did for Vietnam. That is unfortunate, because great powers need to be able to come to grips with the limits of their power, especially in highly troubled times like our own.

Historians explain how the past informs the present

David Kaiser, a historian, has taught at Harvard, Carnegie Mellon, Williams College, and the Naval War College. He is the author of seven books, including, most recently, No End Save Victory: How FDR Led the Nation into War. He lives in Watertown, Mass.

More Must-Reads from TIME

- Cybersecurity Experts Are Sounding the Alarm on DOGE

- Meet the 2025 Women of the Year

- The Harsh Truth About Disability Inclusion

- Why Do More Young Adults Have Cancer?

- Colman Domingo Leads With Radical Love

- How to Get Better at Doing Things Alone

- Michelle Zauner Stares Down the Darkness

Contact us at letters@time.com