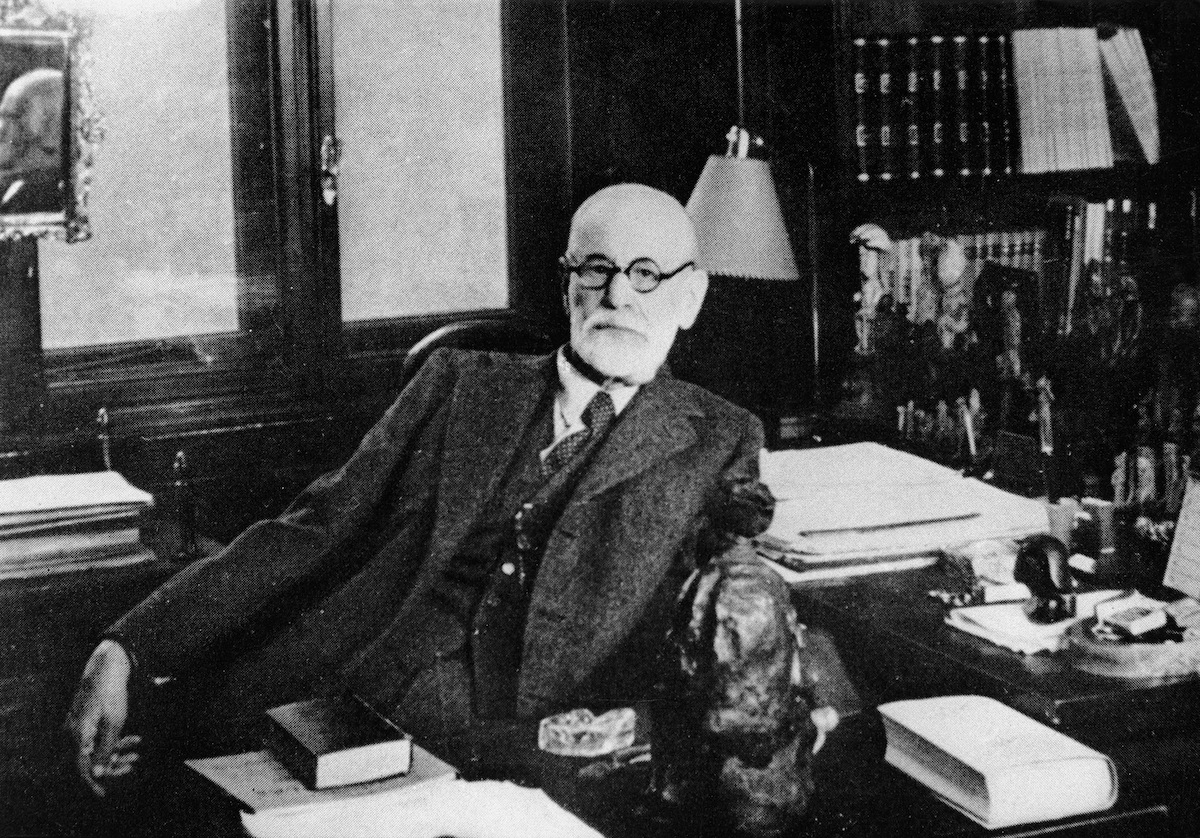

His aversion to America was by no means unconscious: given the choice between safe passage to the United States and increasing oppression at the hands of the Nazis, Sigmund Freud chose to stick with the Nazis.

The father of psychoanalysis — born on this day, May 6, in 1856 — was in his early 80s and “tortured by advanced cancer of the jaw,” per TIME, when he turned down the invitation to the U.S. from a worried nephew who was a publicist in Manhattan.

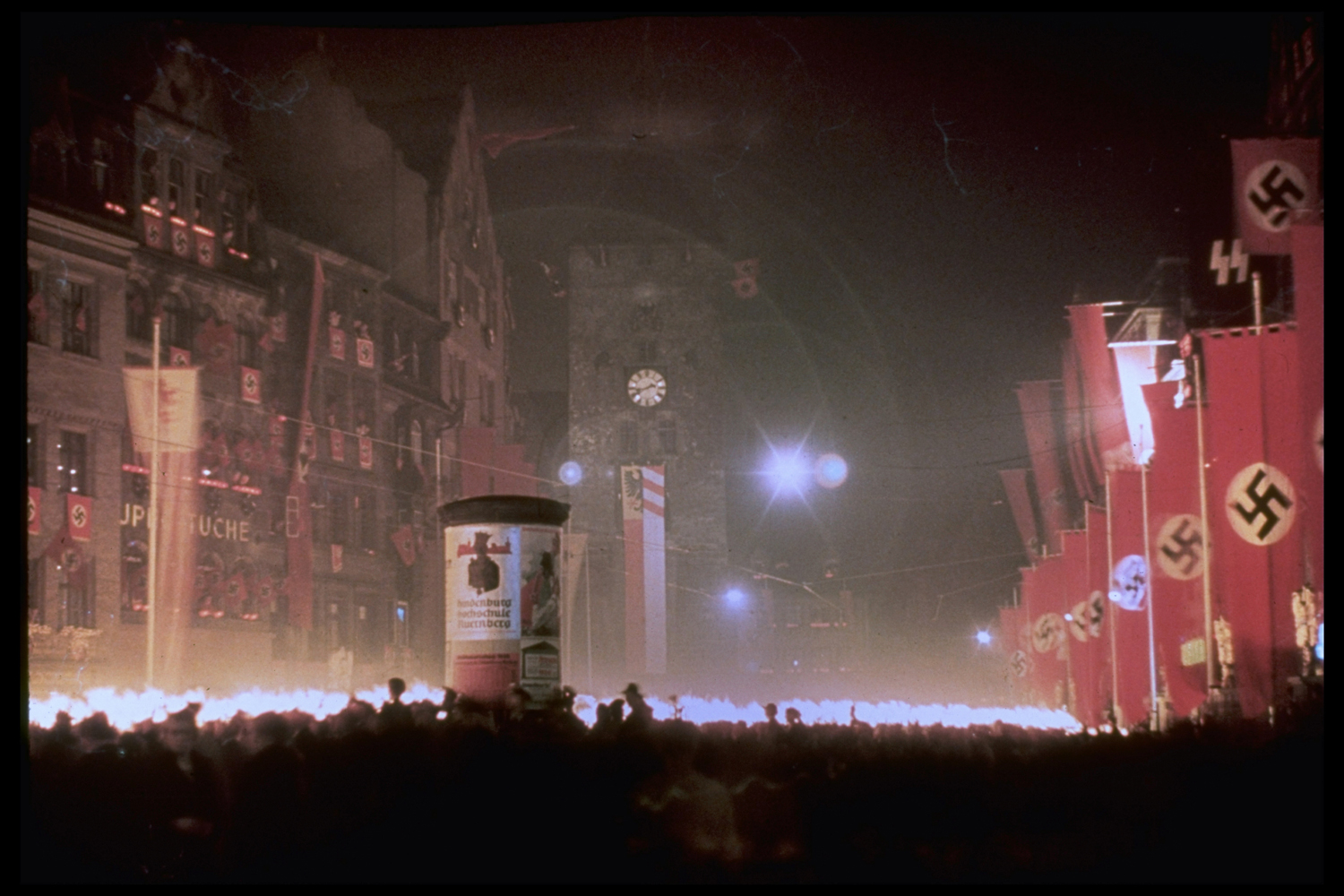

But Freud was no longer safe in Vienna after the Nazi occupation, since the Gestapo was not only targeting Jews in general but psychoanalysts in particular; their fixation on the id’s uncivilized impulses seemed to the Nazis to undermine the dignity of the Volk. In 1933, mobs of Nazi sympathizers had burned Freud’s books, chanting, per The Atlantic, “Against the soul-destroying overestimation of the sex life ─ and on behalf of the nobility of the human soul, we offer the flames the writings of Sigmund Freud.”

After they took Vienna in 1938, the Nazis seized Freud’s money, property, and publishing house, by TIME’s account. Still, he preferred to shelter in place rather than seek asylum among the money-obsessed savages he believed comprised the American populace.

“America is gigantic,” he’s reported to have said, “but a gigantic mistake.”

It took the intervention of one of his star patients, Princess Marie Bonaparte, Napoleon’s great-granddaughter, to uproot him — and for London instead of New York. Bonaparte paid what amounted to ransom to secure Freud’s exit visas, and, according to the Daily Mail, “brokered a deal that enabled him to salvage his library, large sculpture collection, and celebrated couch.”

Freud was ultimately happy with the move, according to TIME, which describes his exile as an idyllic period, despite his near-constant pain:

In a comfortable London house near Regent’s Park, filled with his Greek and Egyptian treasures, Freud answers letters, continues his writing, even treats a few old patients. Every Sunday evening he settles down in the parlor, coddles his five young grandchildren, enjoys a lively card game called tarot with his sons. Always at his call is his nine-year-old chow dog, Lun. During his 16 years of suffering [from cancer], throughout his 15 operations, he has never uttered a word of complaint. Patient and resigned, secure in his fame, he spins out his last thoughts, and basks in the sun.

His wry sense of humor seems never to have abandoned him, either. According to the New York Times, the Nazis had allowed him to leave Austria on the condition that he sign a statement swearing that they had treated him well. He signed, but added a tongue-in-cheek comment offering more praise for German fascism than he’d ever mustered for American democracy: “I can most highly recommend the Gestapo to everyone.”

Read a 1939 cover story about Freud, here in the TIME Vault: Intellectual Provocateur

Color Photos of Hitler Among the Crowds

More Must-Reads from TIME

- Donald Trump Is TIME's 2024 Person of the Year

- Why We Chose Trump as Person of the Year

- Is Intermittent Fasting Good or Bad for You?

- The 100 Must-Read Books of 2024

- The 20 Best Christmas TV Episodes

- Column: If Optimism Feels Ridiculous Now, Try Hope

- The Future of Climate Action Is Trade Policy

- Merle Bombardieri Is Helping People Make the Baby Decision

Contact us at letters@time.com