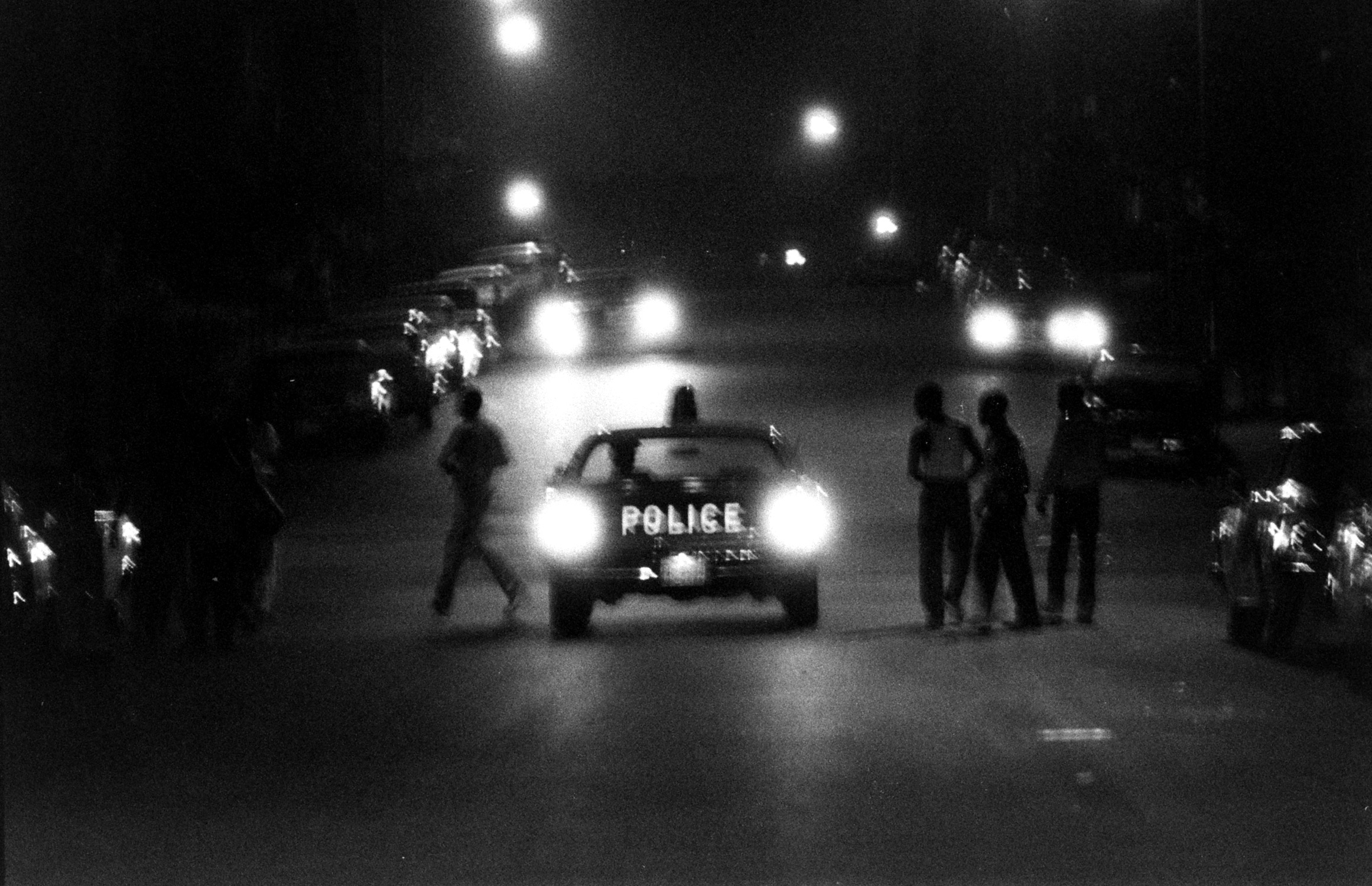

The Daily Show‘s Jon Stewart wasn’t the first to compare this week’s rioting in Baltimore to the 1992 Rodney King Riots in Los Angeles, which were sparked exactly 23 years ago, and he likely won’t be the last — not just because of the confluence of dates and events, but because of how the media covered those events.

During his opening monologue on Tuesday, Stewart called out what he sees as one of the media’s worst habits: a tendency to search for the most sensational images at the expense of context. He compared coverage of Baltimore to similar footage of white people rioting after sporting events and a pumpkin festivals, and he took particular aim at CNN’s Wolf Blitzer, who said, “It’s hard to believe this is going on in a major American city right now,” just a few months after making similar comments about Ferguson.

“These cyclical eruptions appear like tragedy cicadas,” Stewart said, “Depressing in their similarity, predictability and intractability.”

Even President Obama expressed that he shared Stewart’s frustrations with the media during a Tuesday press conference. “If we really wanted to solve the problem, we could,” he said, noting that coverage of the violence dwarfed coverage of peaceful protests from previous days. “It would require everybody saying, ‘This is important, this is significant,’ and not just pay attention to these communities when a CVS burns or a young man gets shot or has his spine snapped.”

Those criticisms will sound familiar to those who read TIME critic Richard Schickel’s take on the Los Angeles riots in the magazine’s May 11, 1992 issue:

Television’s mindless, endless (generally fruitless) search for the dramatic image — particularly on the worst night, Wednesday — created the impression that an entire city was about to fall into anarchy and go up in flames. What was needed instead was geography lessons showing that rioting was confined to a relatively small portion of a vast metropolis and that violent incidents outside that area were random, not the beginning of a concentrated march to the sea via Rodeo Drive.

More than that, TV needed to offer perspective. Anchors everywhere plied field reporters with Big Picture questions. But that wasn’t their job. Their job was to create a mythical city, a sort of Beirut West, views of which would keep many viewers frozen in fear to their Barcaloungers. And, incidentally, send a few of them out to join in the vicious fun. Their masters provided these journalists with almost no opportunity to do what many of them manifestly wanted to do: interrogate authority about strategy and timetables; question experts who knew something about the patterns of urban unrest; follow up a hundred human-interest stories.

…The basic function of journalism is selection. It is through that skill that a medium earns civic responsibility and achieves public trust. Just because we have evolved a technology that can create the impression of encompassing events instead of merely observing them — and a race of iron-bottomed anchorpeople to lend friendly authority to this illusion — does not mean that either should be employed without restraint.

Read the full story here: How TV Failed to Get the Real Picture

Read TIME’s cover story about the Los Angeles riots, here in the TIME Vault: The Fire This Time

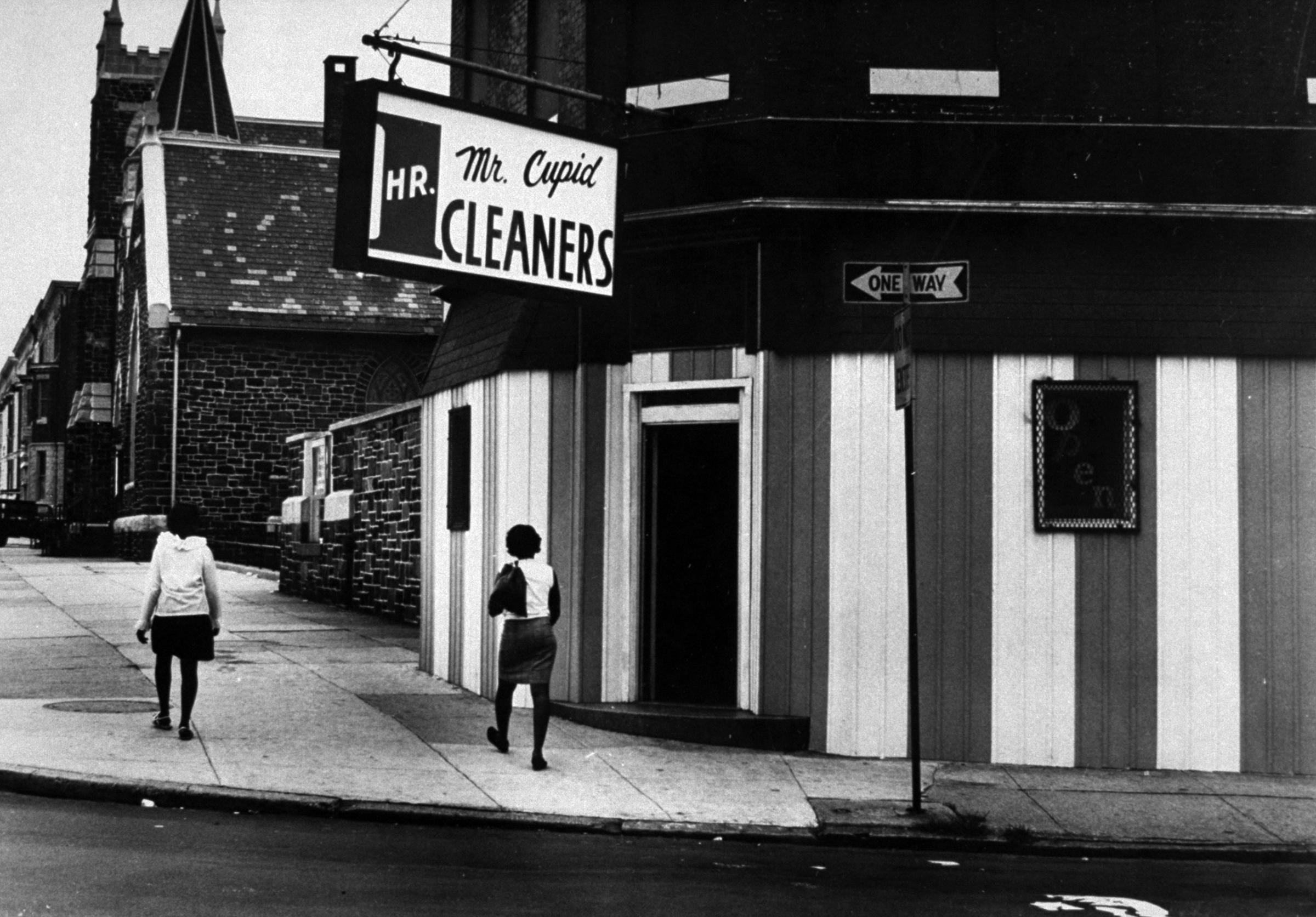

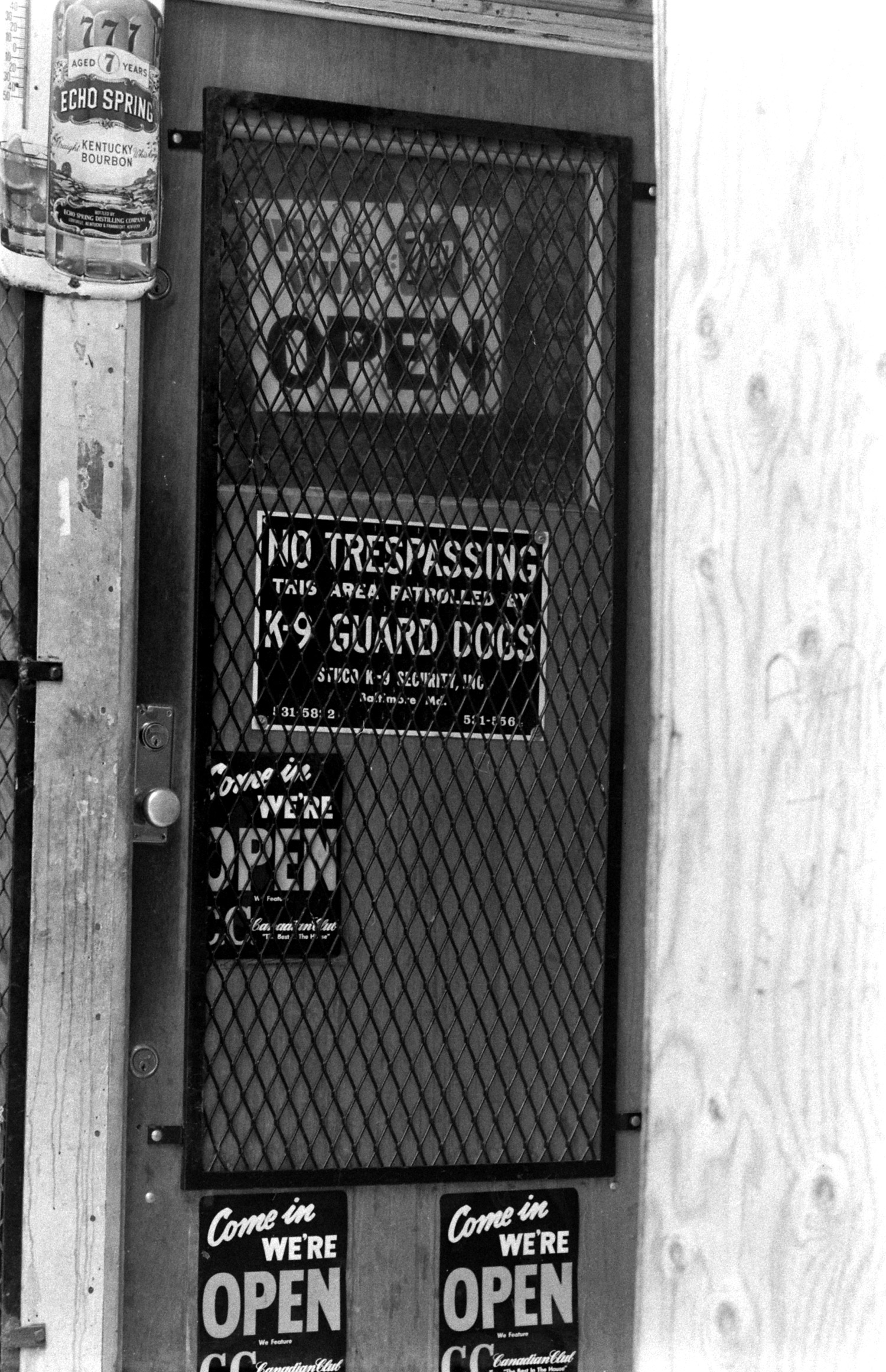

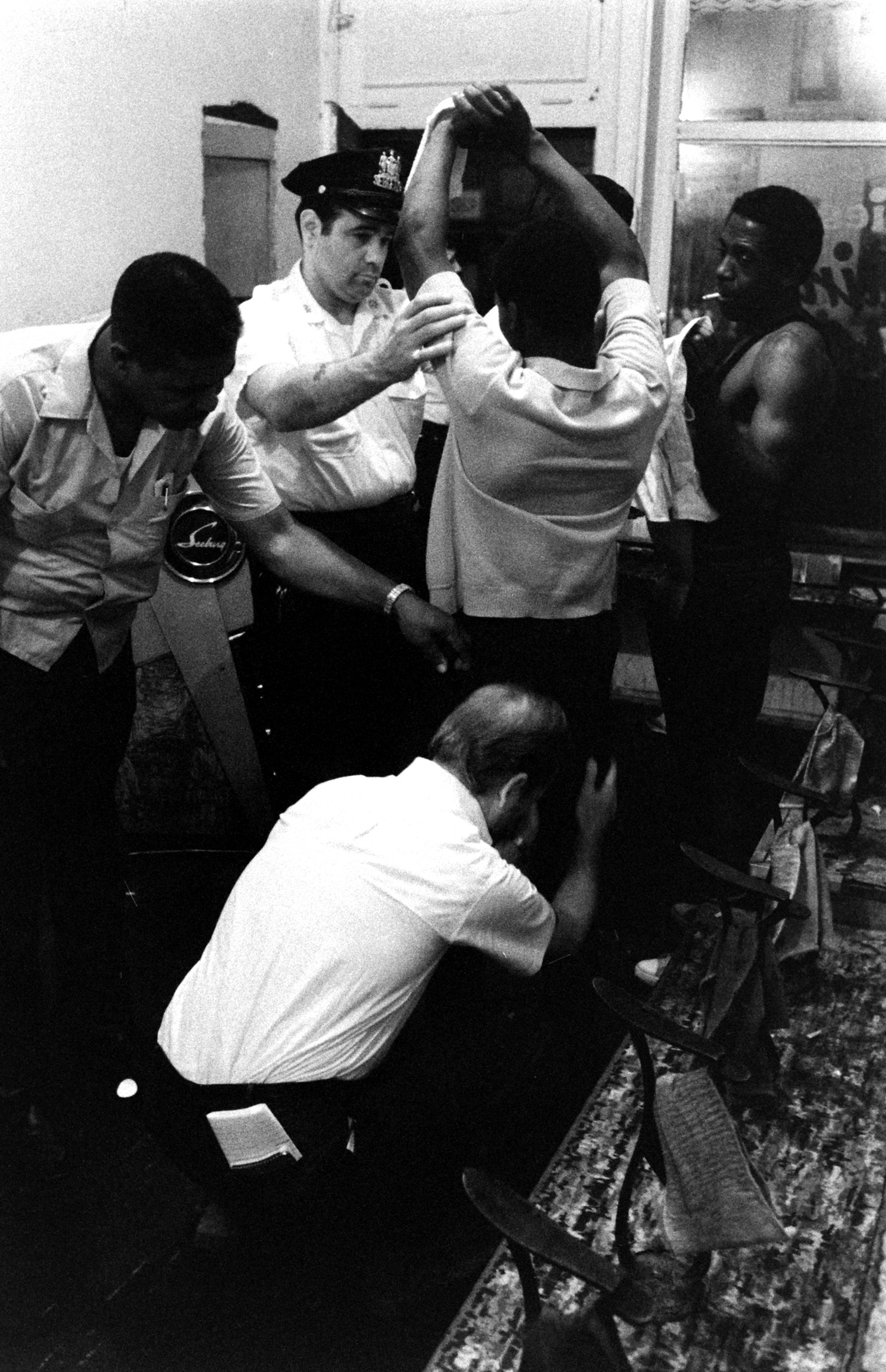

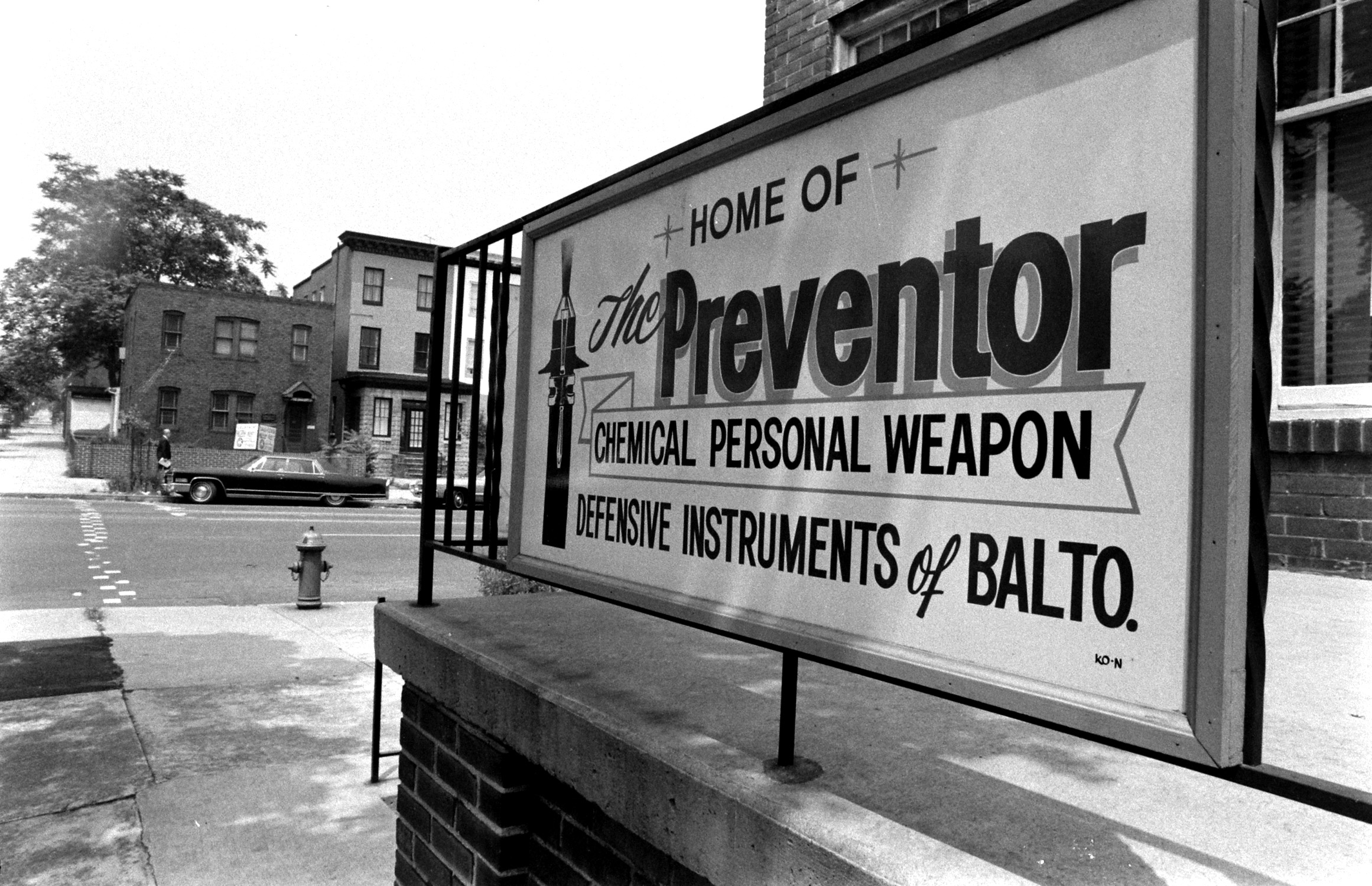

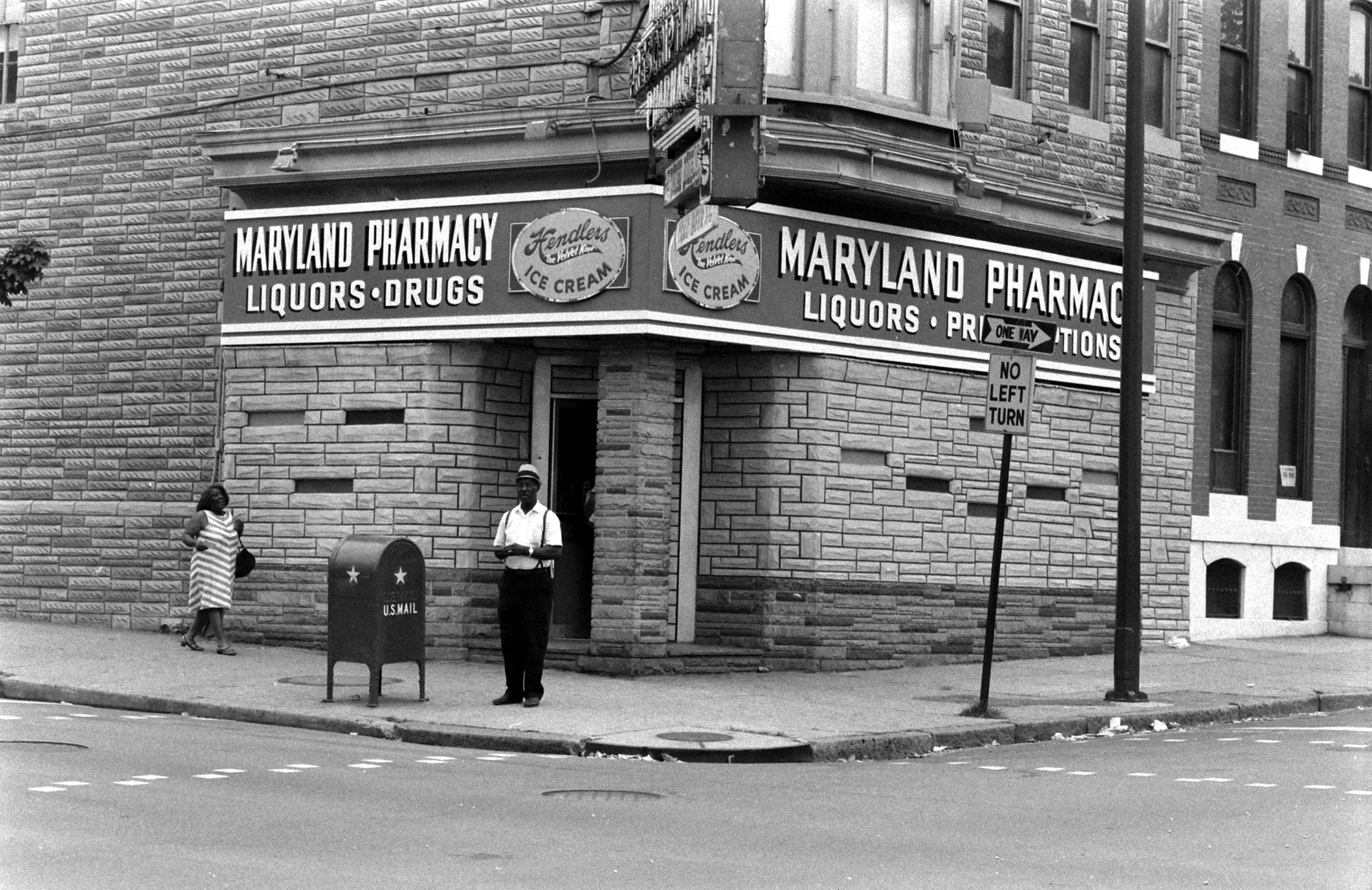

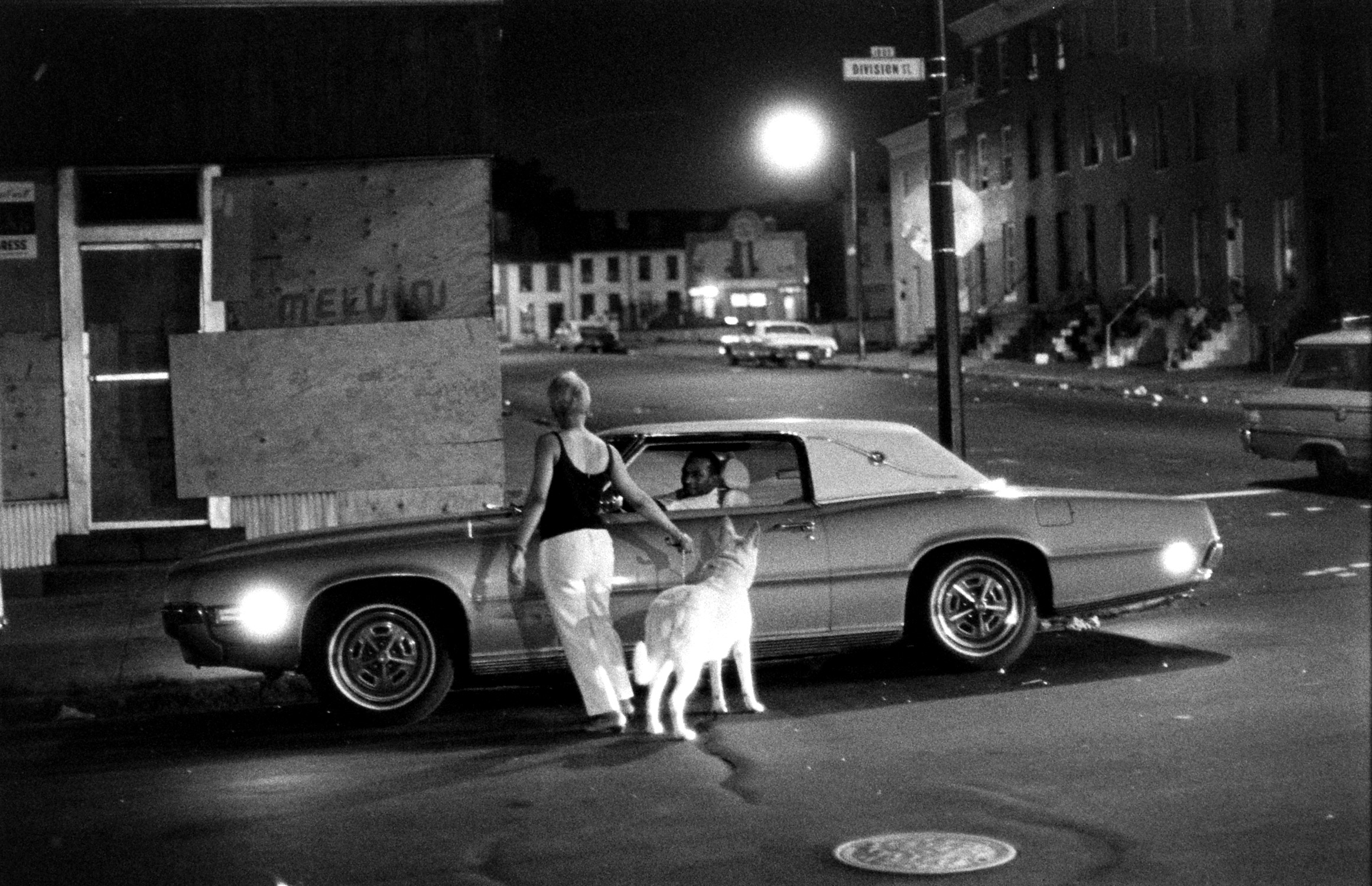

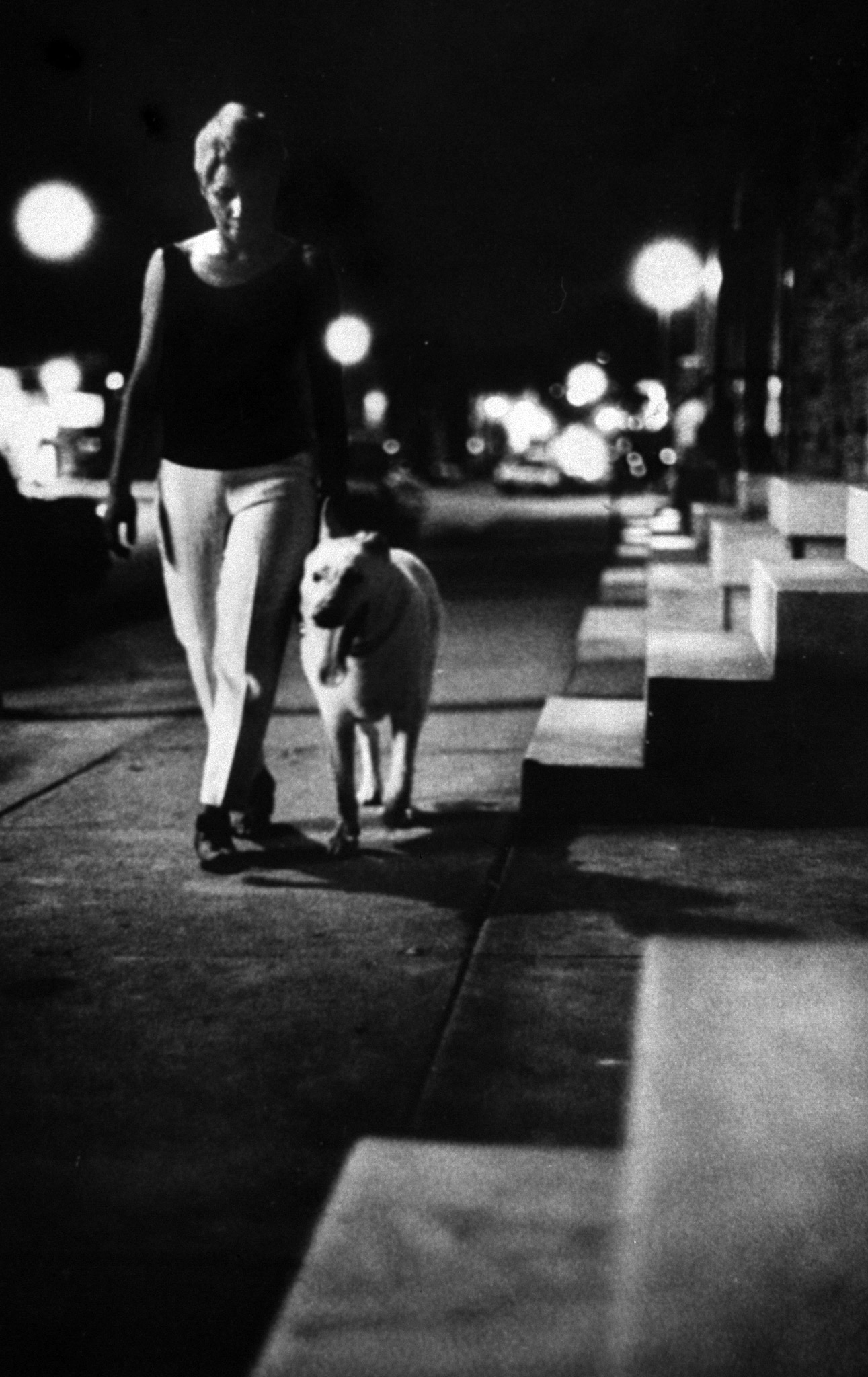

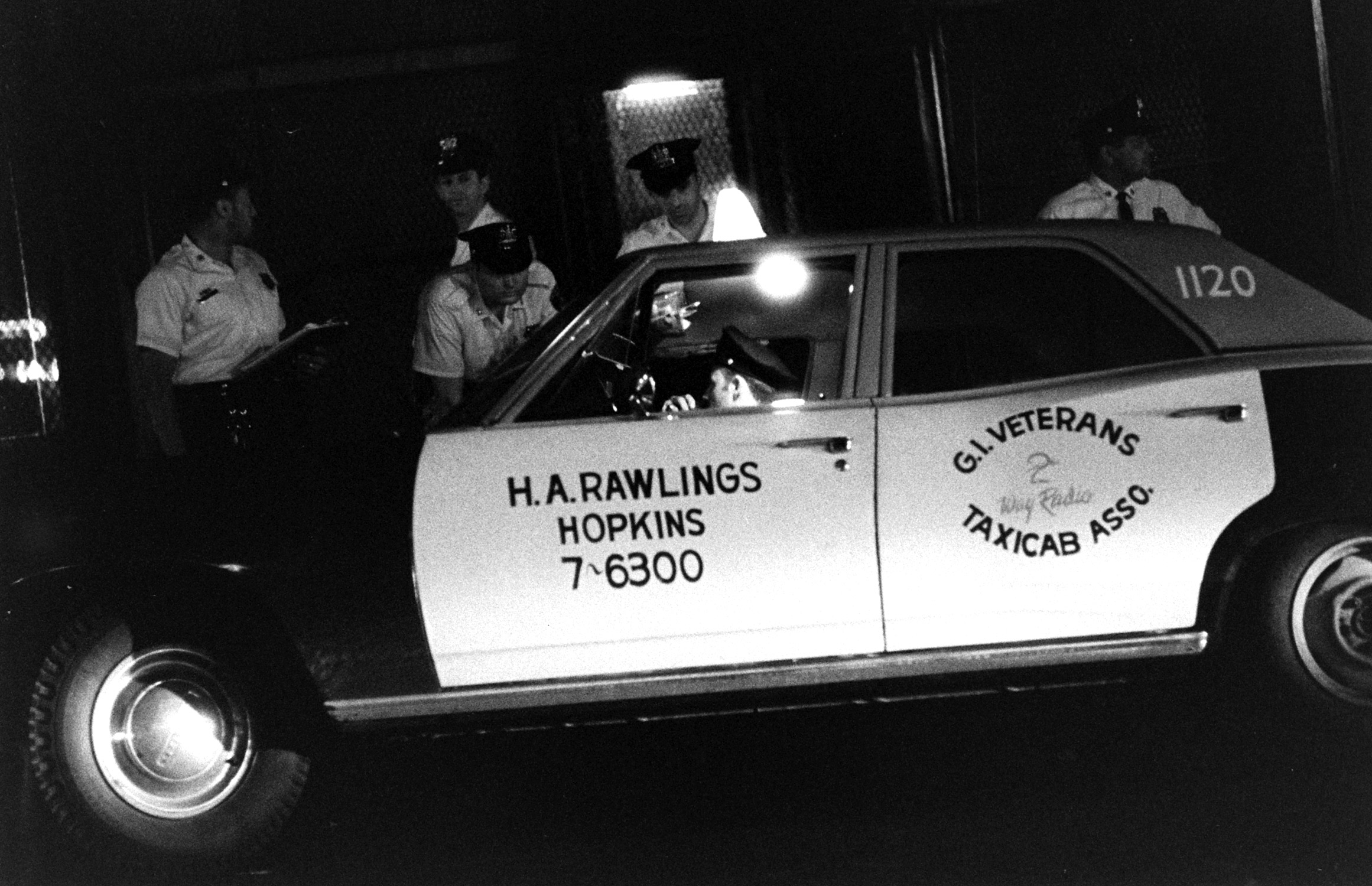

What Baltimore Looked Like in the Aftermath of the Riot of 1968

More Must-Reads from TIME

- How Donald Trump Won

- The Best Inventions of 2024

- Why Sleep Is the Key to Living Longer

- Robert Zemeckis Just Wants to Move You

- How to Break 8 Toxic Communication Habits

- Nicola Coughlan Bet on Herself—And Won

- Why Vinegar Is So Good for You

- Meet TIME's Newest Class of Next Generation Leaders

Write to Nolan Feeney at nolan.feeney@time.com