In the 20 years that I have lived in Baltimore City, I have seen guns fired only twice; in each instance the targets were black men and the shooters were police. In one case the officer was trying to stop a group of men who had apparently stolen a car. They bailed out in front of my house, and as they were running away, the officer fired, but missed. In the second case the officer’s aim was better; an assailant held up a medical student on a bicycle, then ran through traffic right in front of our car. An off-duty cop saw the scuffle and fired. He turned out to be a 14-year-old with a BB gun. The boy lay in the street, shot in the stomach; my 12-year-old son and I waited until the police told us to move on. I called my district and set up an appointment with a detective. No one ever came to question me.

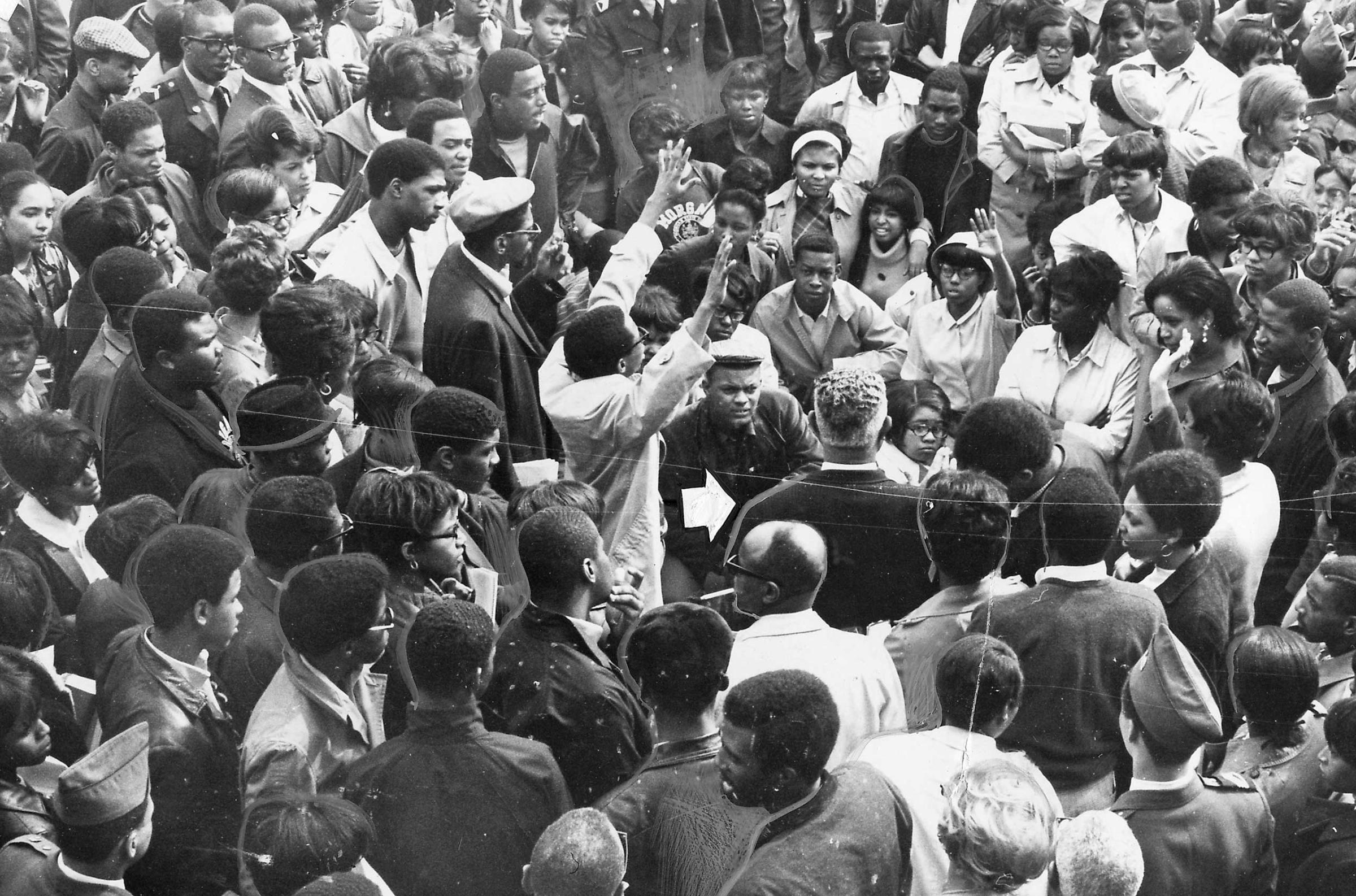

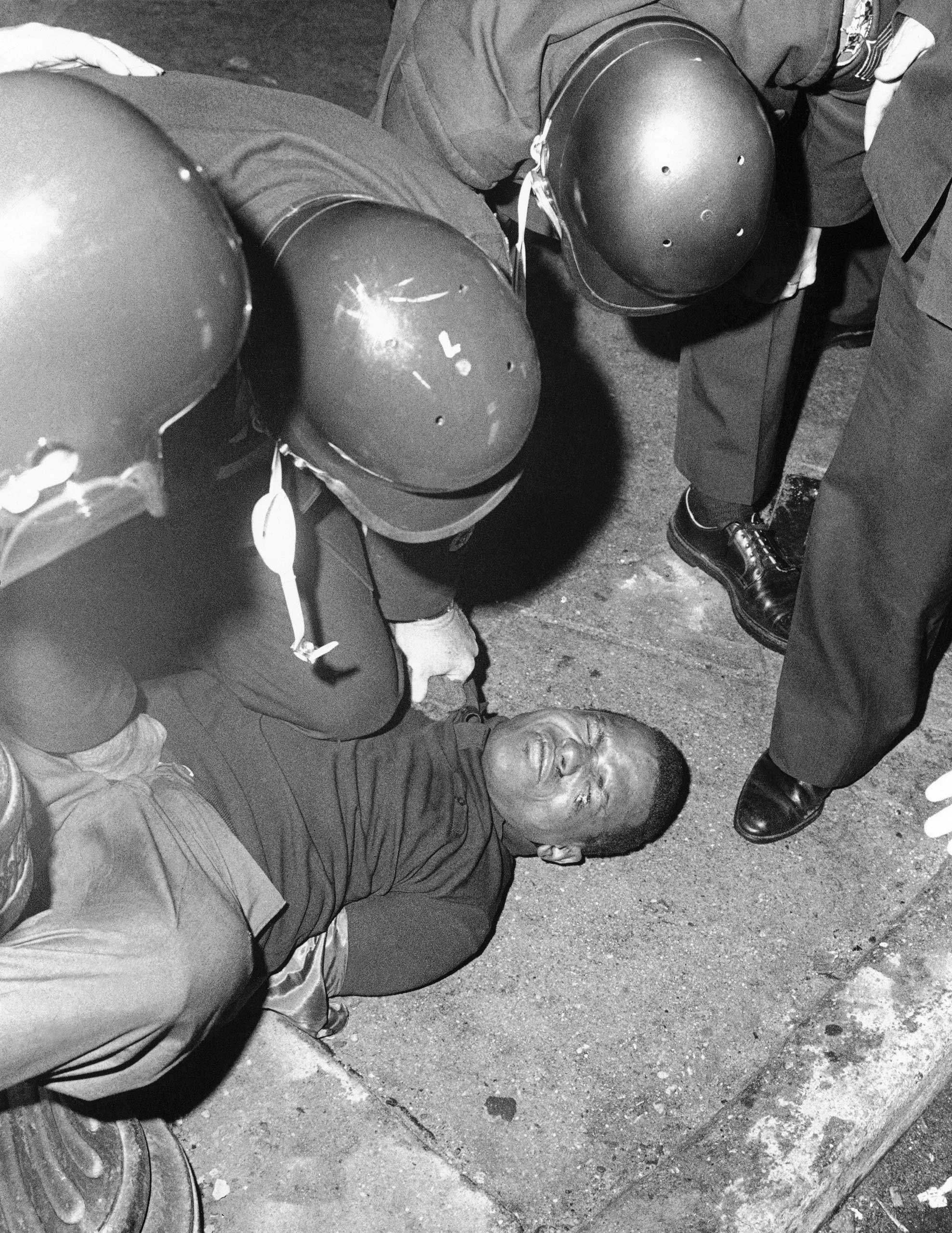

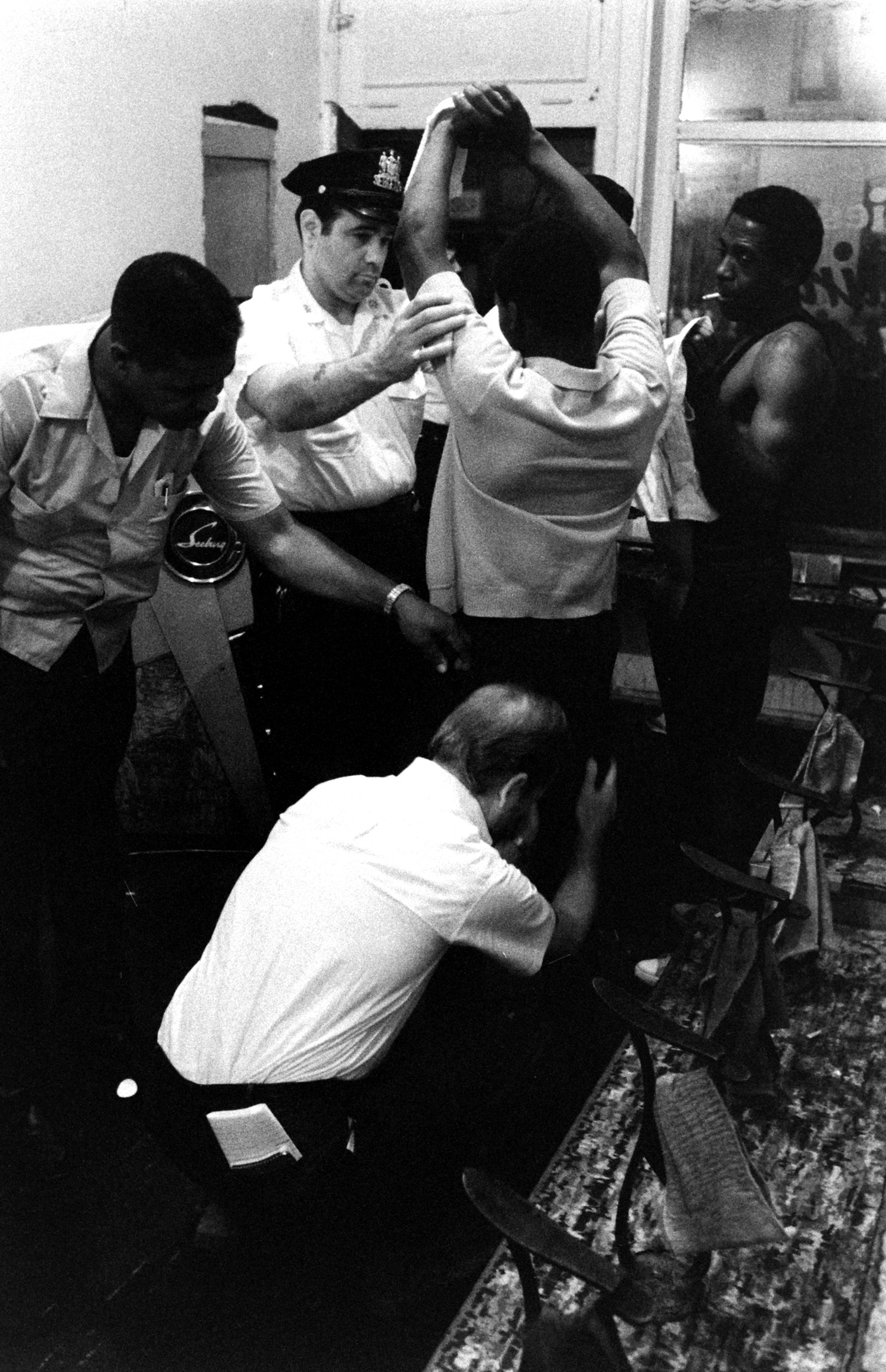

Those incidents came back to me this week when the death of Freddie Gray triggered days of peaceful protests that splintered into something uglier on Saturday, and anti-police violence erupted on Monday. But those weren’t the only moments from the past that seemed worth thinking about. The looting and arson led to comparisons to the unrest that followed the assassination of the Rev. Dr. Martin Luther King, Jr.—and, as an assistant professor of history at the University of Baltimore who has studied Baltimore in 1968, I can see a number of similarities. After several days of peaceful commemoration of Dr. King’s death, disenfranchised youth instigated disturbances in fifteen neighborhood commercial districts. Curfews were imposed, just as they were in Baltimore this week, and hundreds of citizens were eventually swept into custody. During both of the crises, members of the clergy of all faiths walked the streets in attempts to restore order.

But the real link between the two moments, 1968 and today, runs deeper than that. It’s not about the appearance of similarity, but rather the causes and effects.

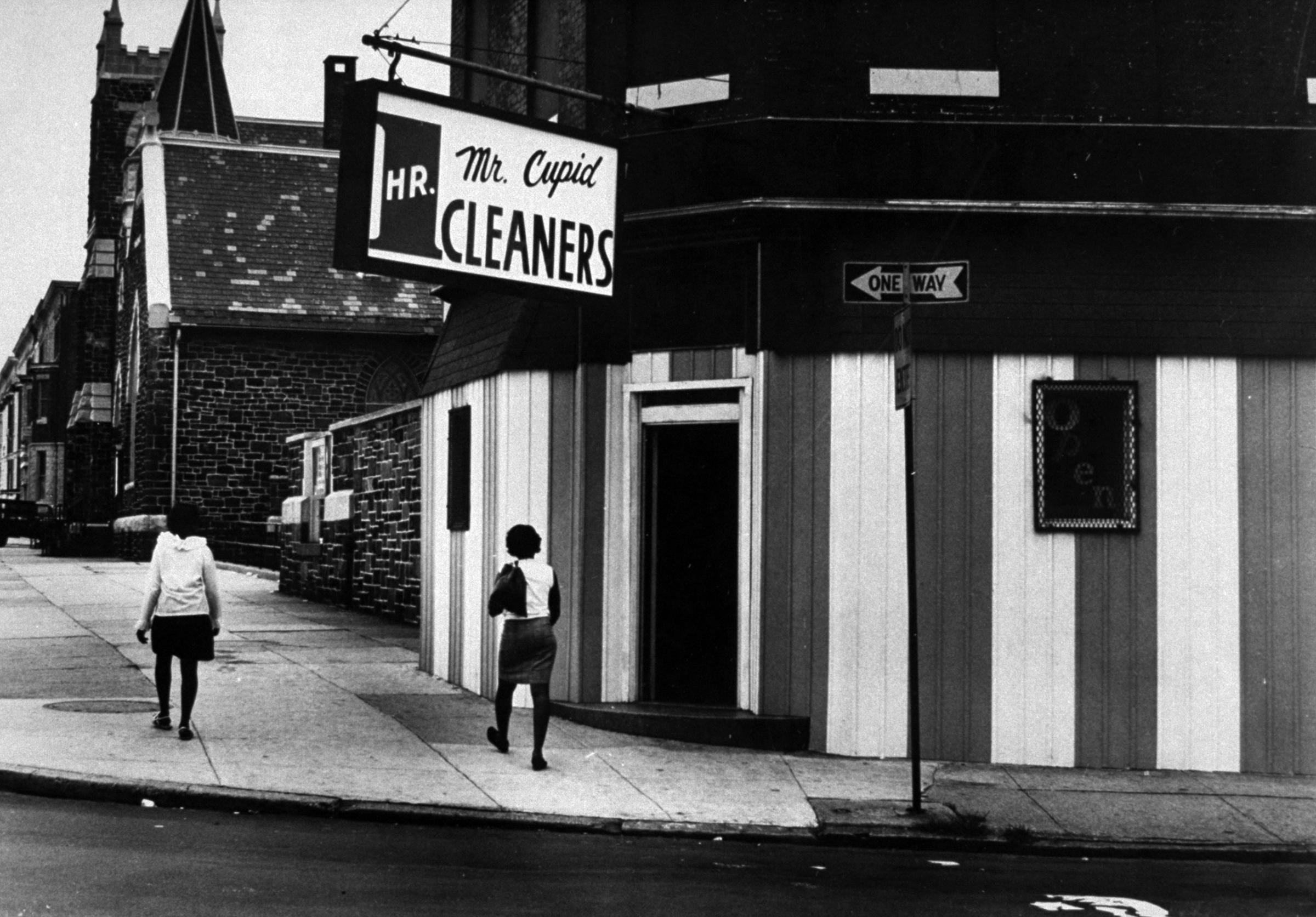

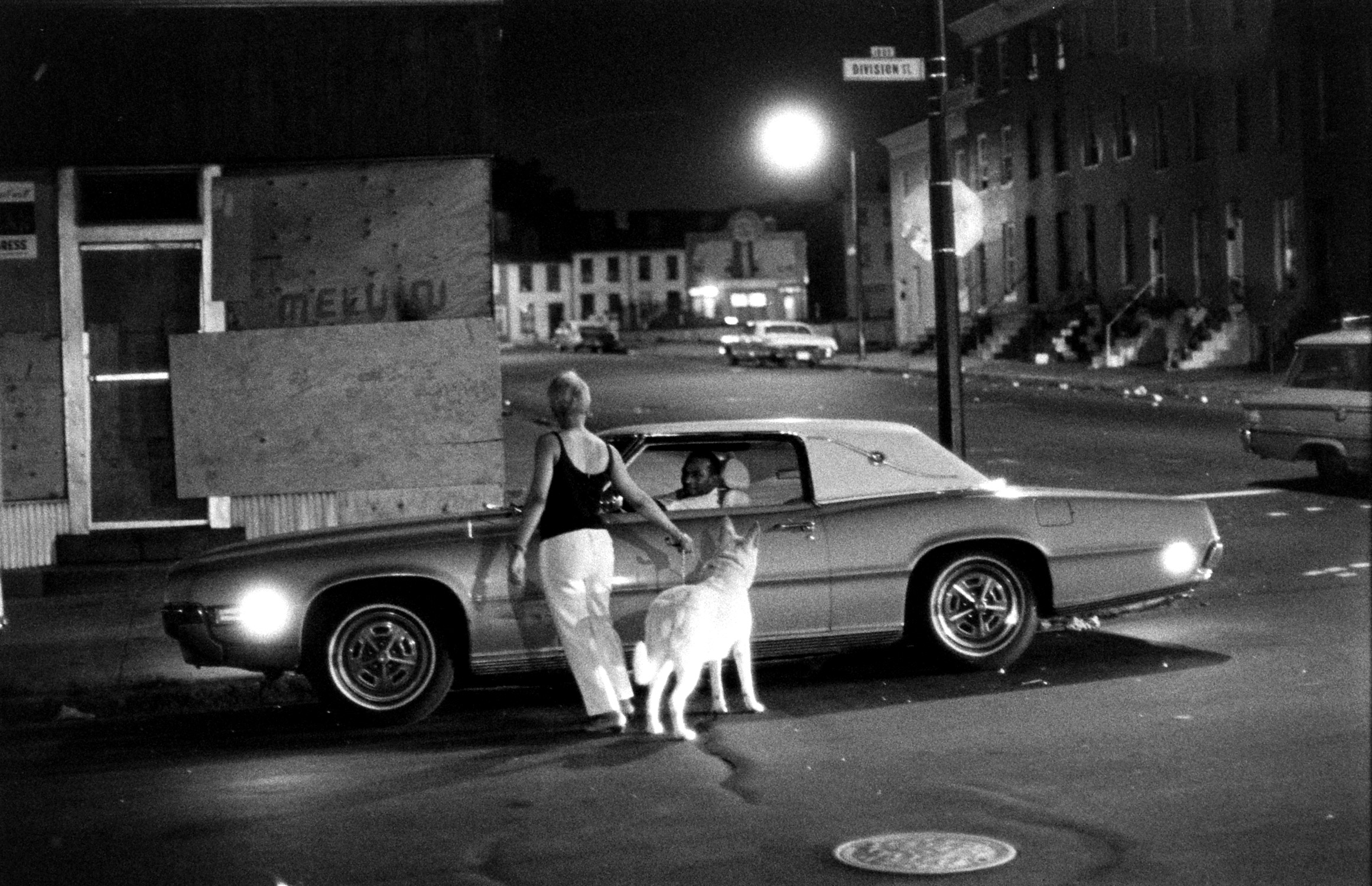

As UB discovered in a community-based, multi-disciplinary examination of the riots 40 years later, the causes and consequences of urban unrest are complex and multifaceted. As part of our project, our diverse student body interviewed their friends and family, and we heard stories that illustrated deep systemic trends that led to generations of anger and frustration: practices in the private sector like residential covenants that forbade sales to black and Jewish buyers, federal policies like redlining that discouraged bank loans to poor and aging neighborhoods, urban renewal policies that used federal funds to build highways that cut neighborhoods off from the rest of Baltimore; limited job opportunities as Baltimore’s blue-collar jobs began to evaporate. All of those forces had been at work long before Dr. King’s assassination, and, as we see violence along the same streets almost five decades later, Baltimoreans still feel their effects today.

Baltimore Protests, Then and Now

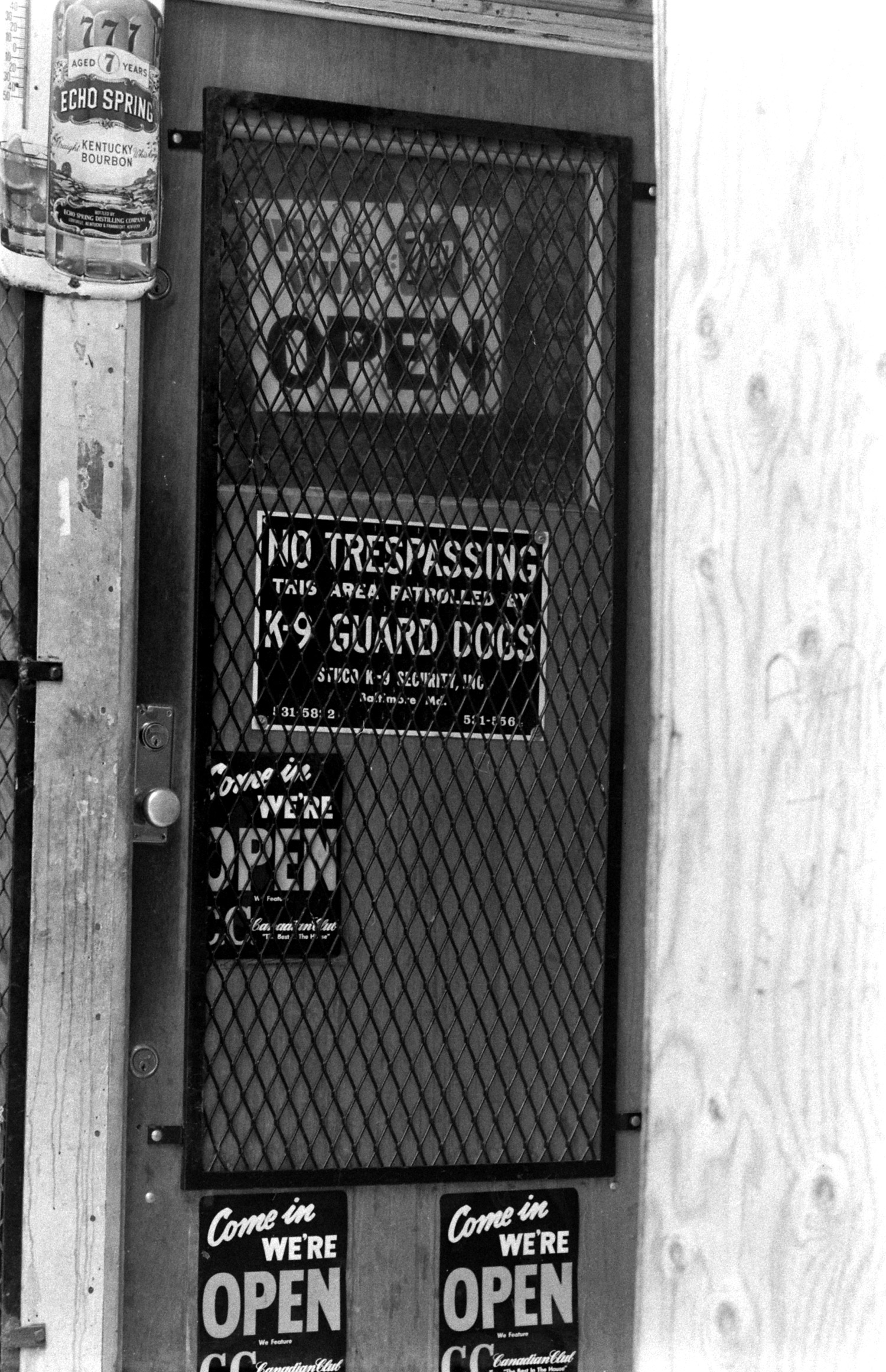

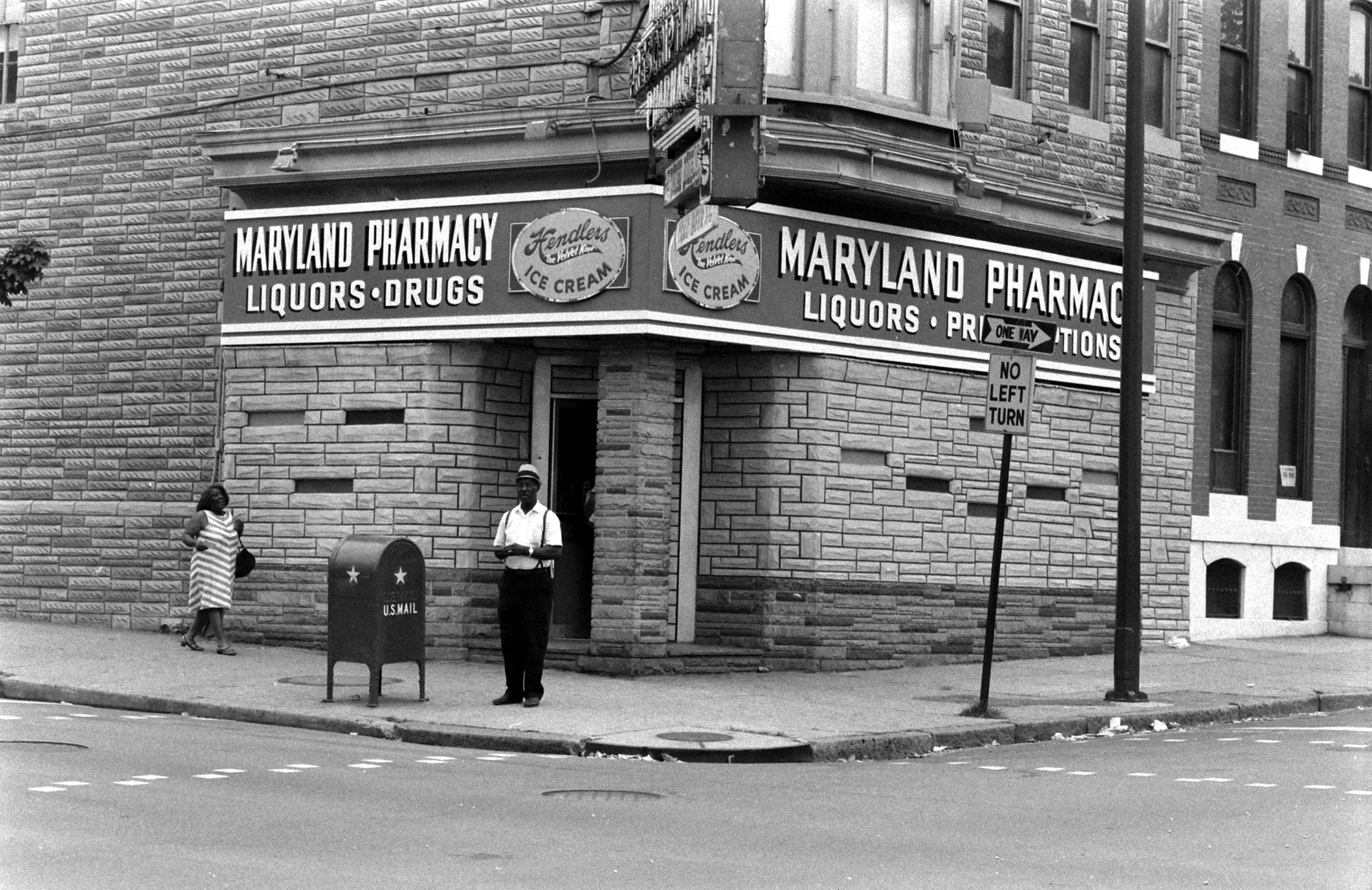

We also heard stories about businesses that were destroyed after families had poured years of effort and capital into them. In 1968 the Pats family lost its pharmacy on West North Avenue, just a few blocks from the CVS that burned this Monday evening. Their business was looted, then their entire block was burned, including their apartment. Their neighbors, who lost their jewelry store, had been relocated to Baltimore after surviving the Holocaust. Baltimore’s retail sector has still not recovered in many areas of the city. A number of neighborhoods have been declared food deserts, and no department store exists within the city limits. When a Target arrived at Mondawmin Mall and hired city residents, Baltimoreans welcomed it. But on Monday night we watched with dismay as looters ran out of Mondawmin, their arms full of merchandise.

In 1968, the governor of Maryland called out the National Guard, just as Governor Larry Hogan did on Monday night, and soon tanks patrolled the city streets. The unrest quieted, and by the end of the week the Orioles held opening day on schedule.

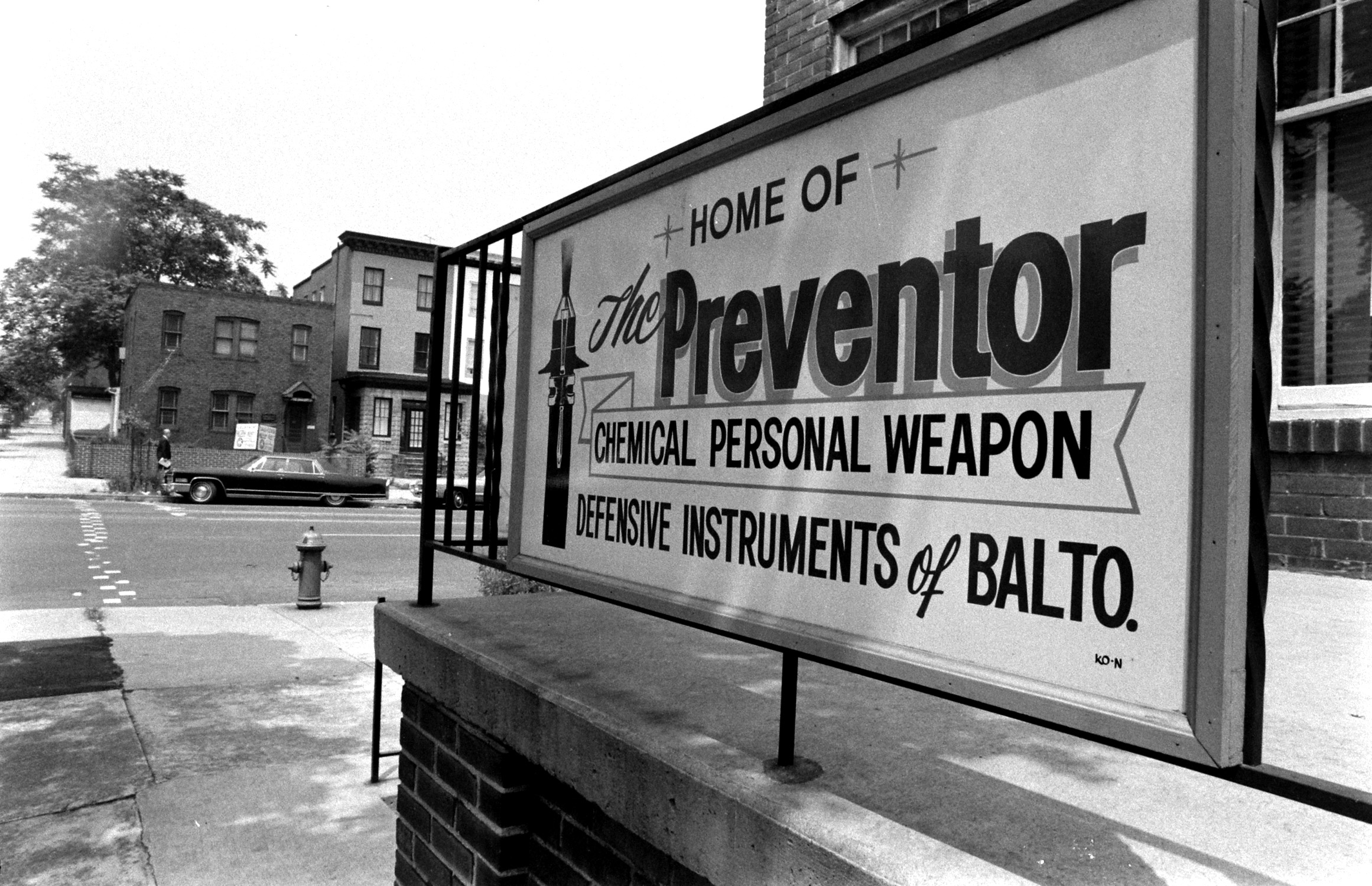

Here’s where the stories diverge. Maryland’s then-governor, Spiro Agnew, rode the wake of Baltimore’s disturbances right into the White House, using his tough-on-crime reputation to become Richard Nixon’s vice-presidential running mate. It is too simplistic to say that the policing approach Agnew advocated led directly to the kind of practices that killed Freddie Gray, Michael Brown, and Eric Garner. We cannot exclude from the list of causes Nixon’s War on Drugs, the crack epidemic of the 1980s and ‘90s, the growth of the prison-industrial complex, and the continuing hemorrhaging of blue-collar jobs from America’s aging industrial cities—but the reaction to the urban riots of the 1960s certainly started us down this path.

The similarities can stop. Knowledge of the aftermath of 1968 can help prevent its repetition. In the early 1970s law and order policing reinforced divisions around race, class, and geography in an attempt to lock up the problems instead of addressing them. We can learn from those mistakes. On Tuesday morning the NAACP announced that they would open a satellite office in Sandtown-Winchester, Freddie Gray’s neighborhood, to provide counsel to residents on a host of legal issues, including police misconduct. An external oversight board to monitor reports of police violence would serve as a powerful partner in this effort. Out on the streets on Tuesday morning, Baltimoreans worked together to clean up the debris from the night. I hope that as we work we will find a chance to tell each other our stories, and that this time we will listen.

Historians explain how the past informs the present

Elizabeth M. Nix is a professor of legal, ethical and historical studies at the University of Baltimore, and co-editor with Jessica Elfenbein and Thomas Hollowak of Baltimore ’68: Riots and Rebirth in An American City.

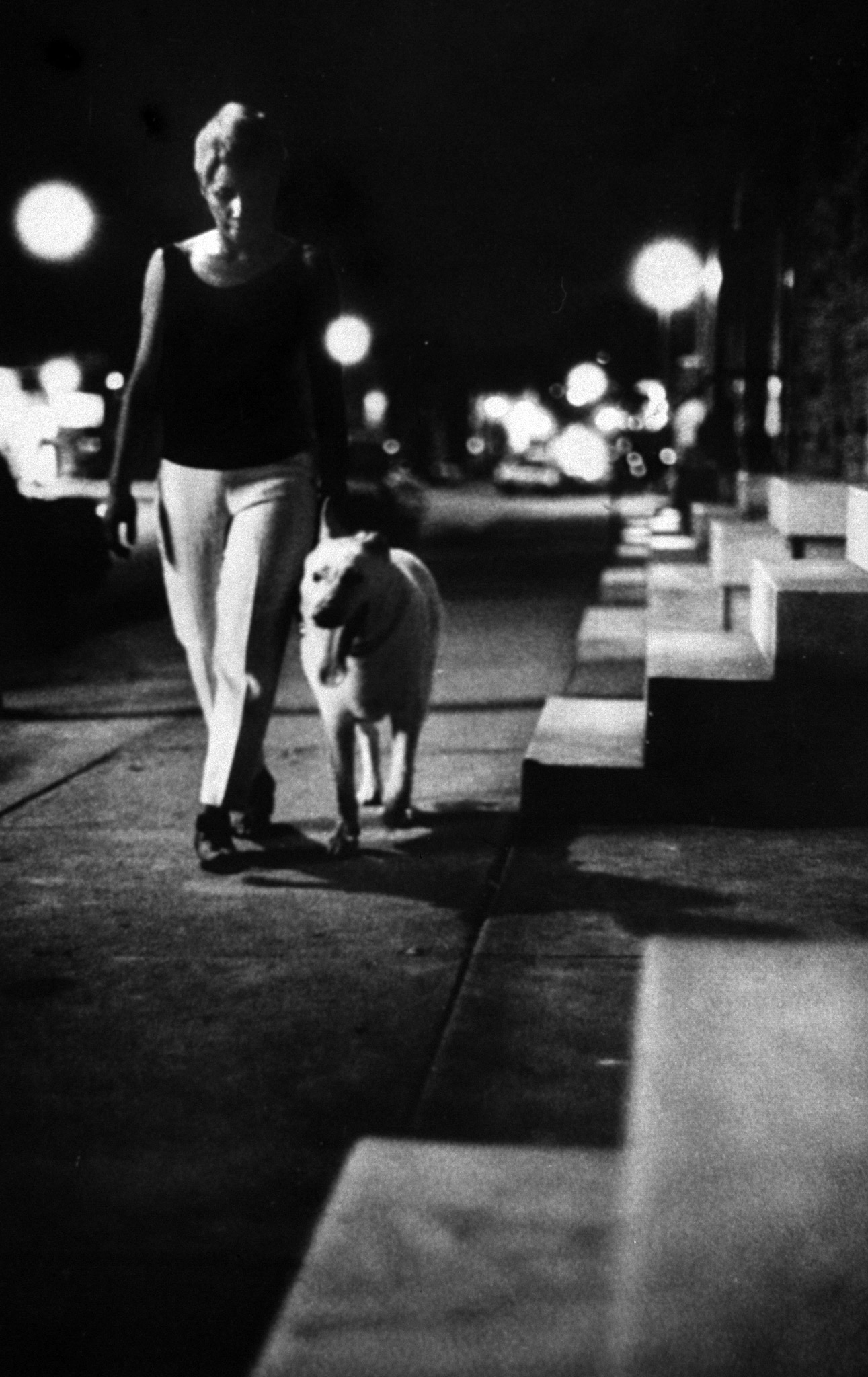

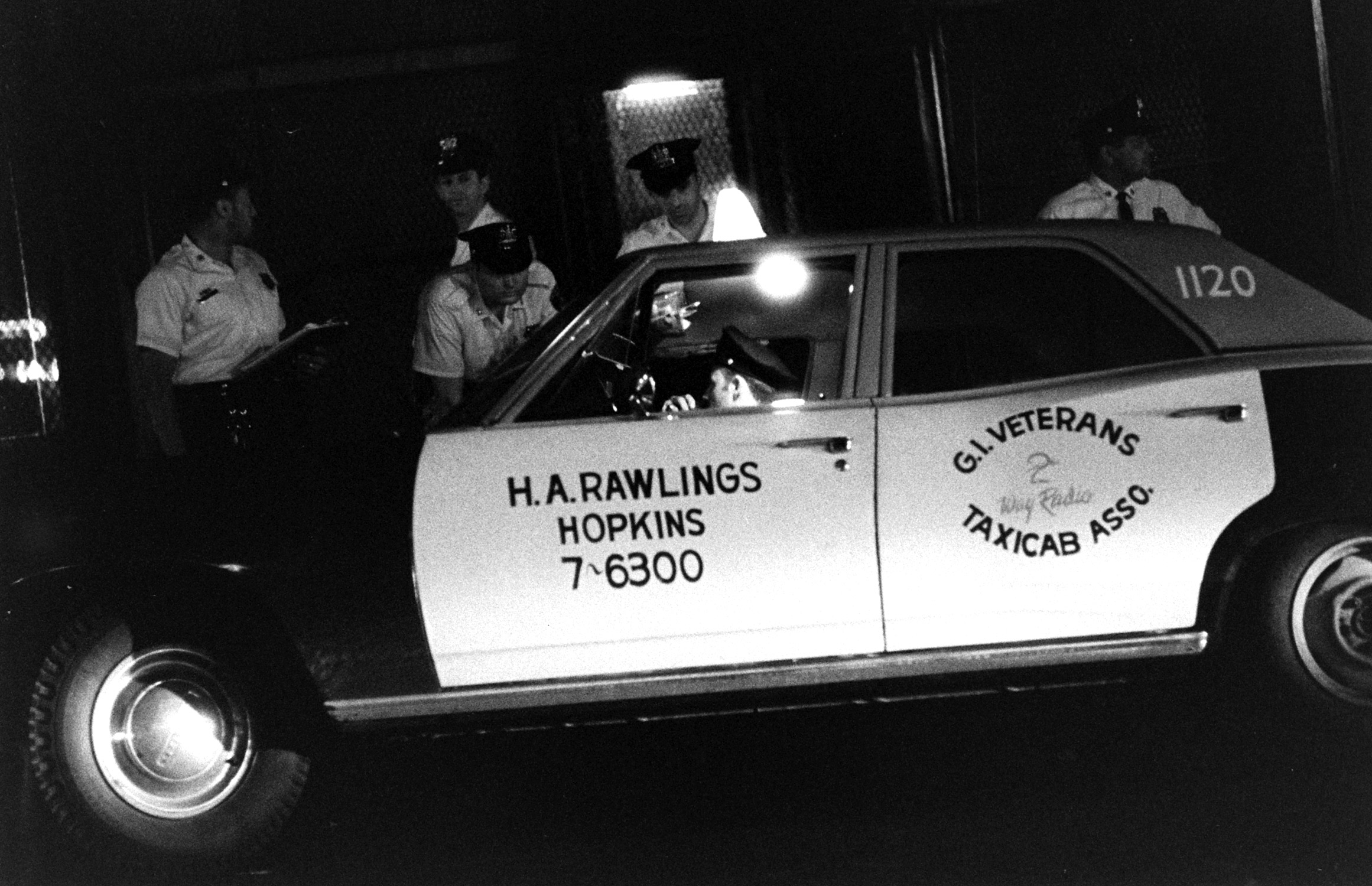

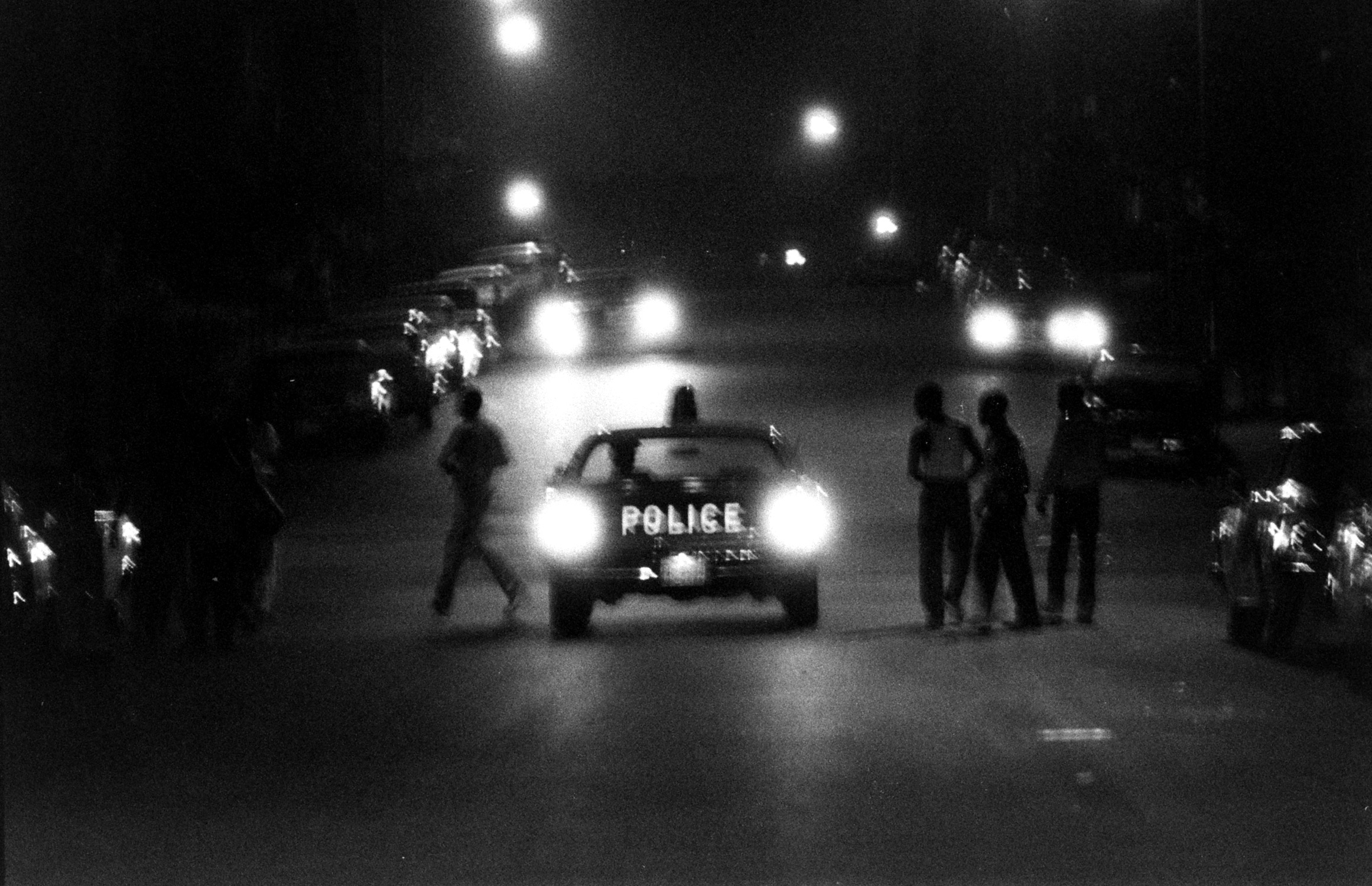

What Baltimore Looked Like in the Aftermath of the Riot of 1968

More Must-Reads from TIME

- Cybersecurity Experts Are Sounding the Alarm on DOGE

- Meet the 2025 Women of the Year

- The Harsh Truth About Disability Inclusion

- Why Do More Young Adults Have Cancer?

- Colman Domingo Leads With Radical Love

- How to Get Better at Doing Things Alone

- Michelle Zauner Stares Down the Darkness

Contact us at letters@time.com