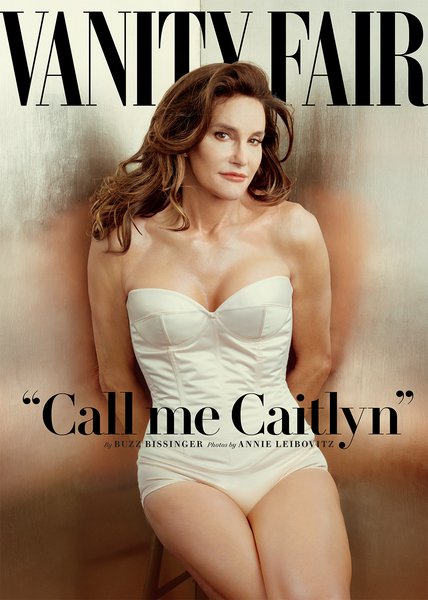

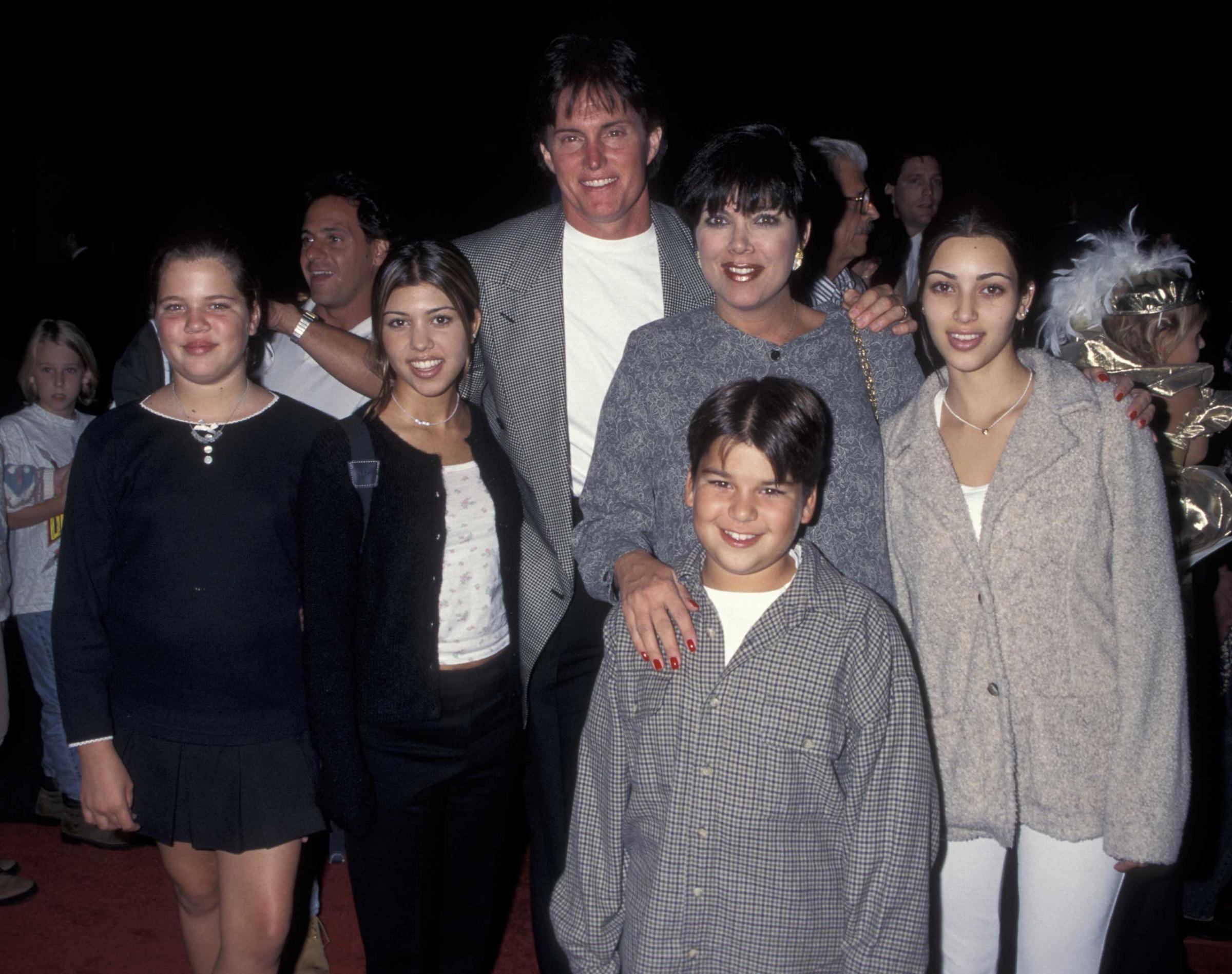

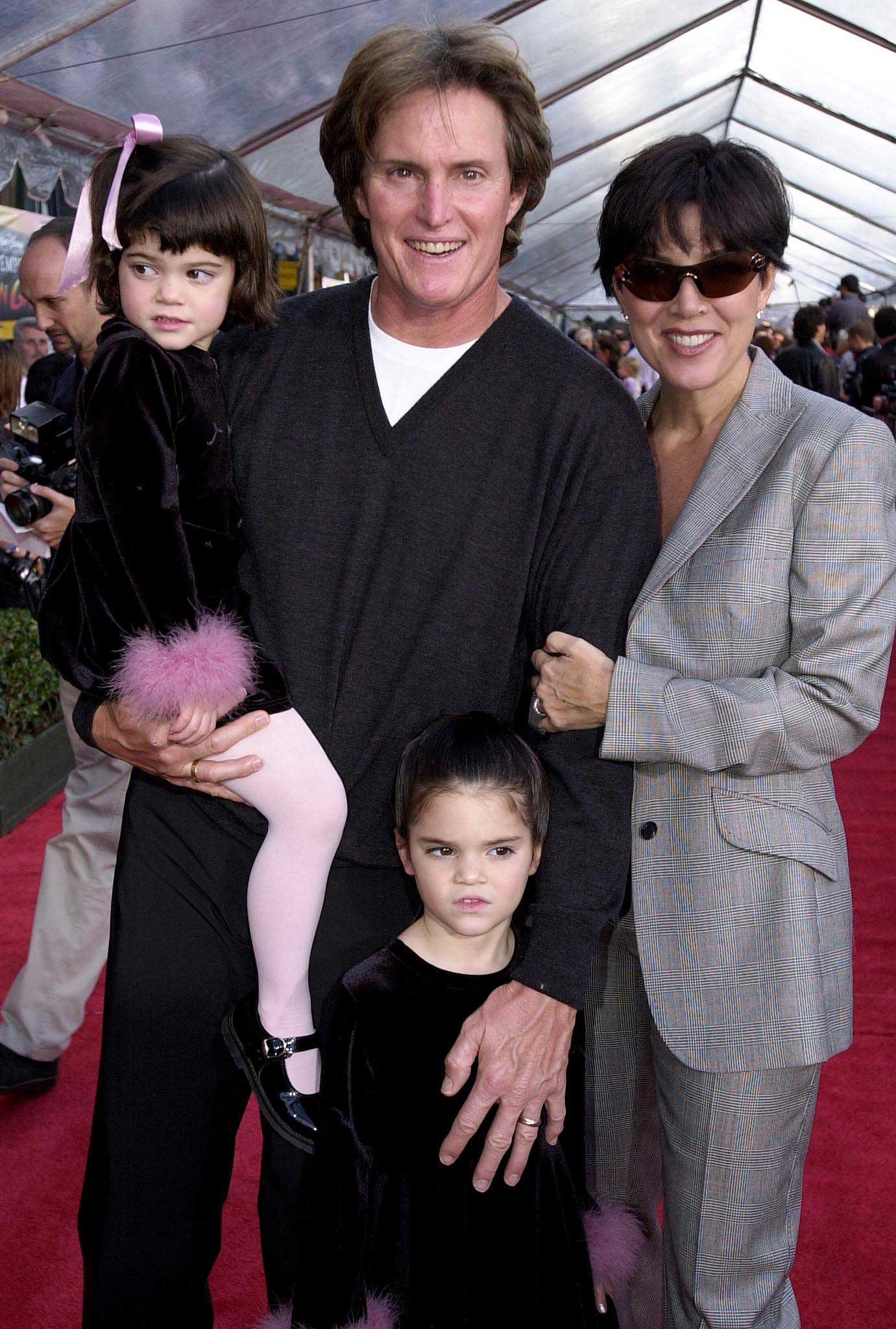

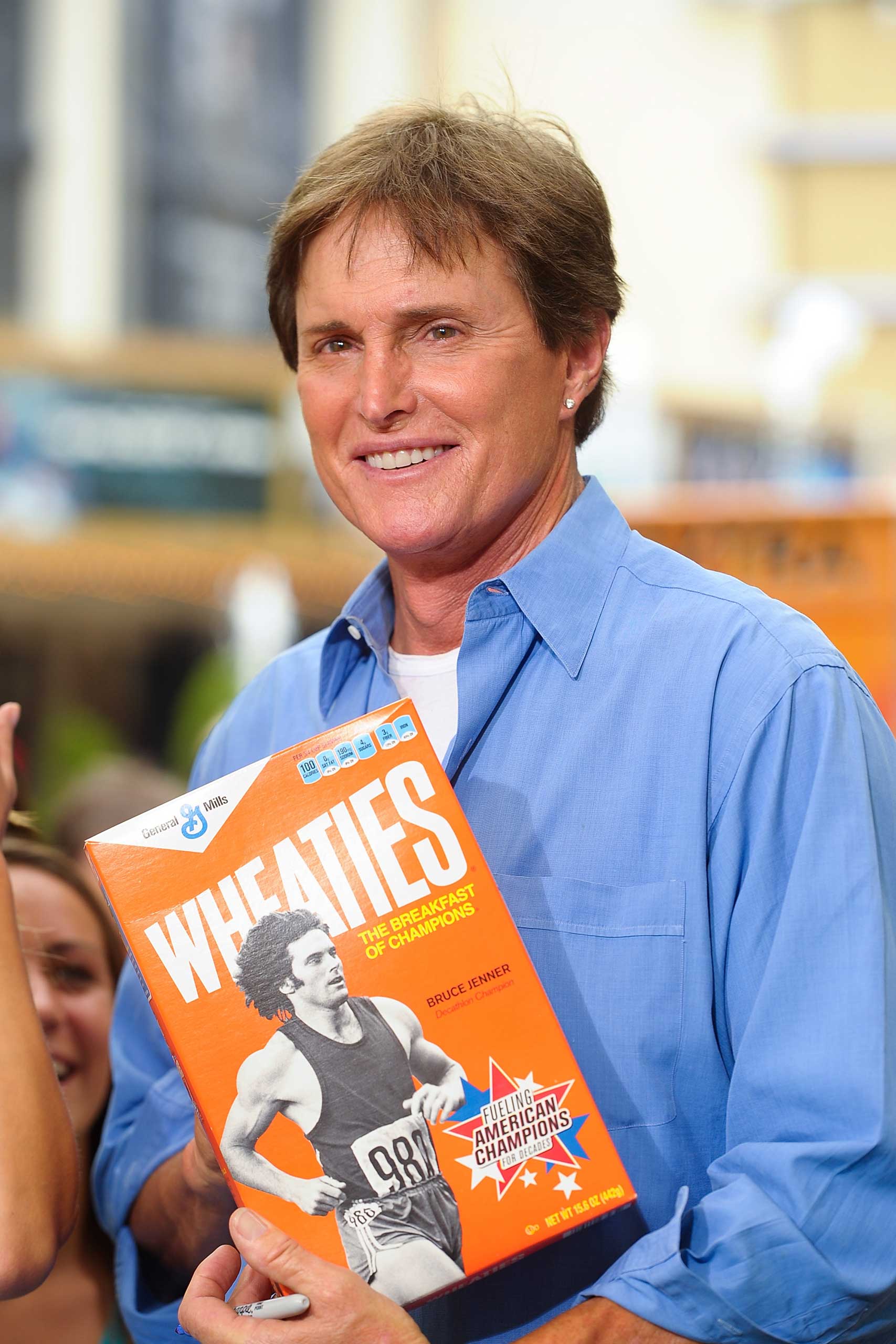

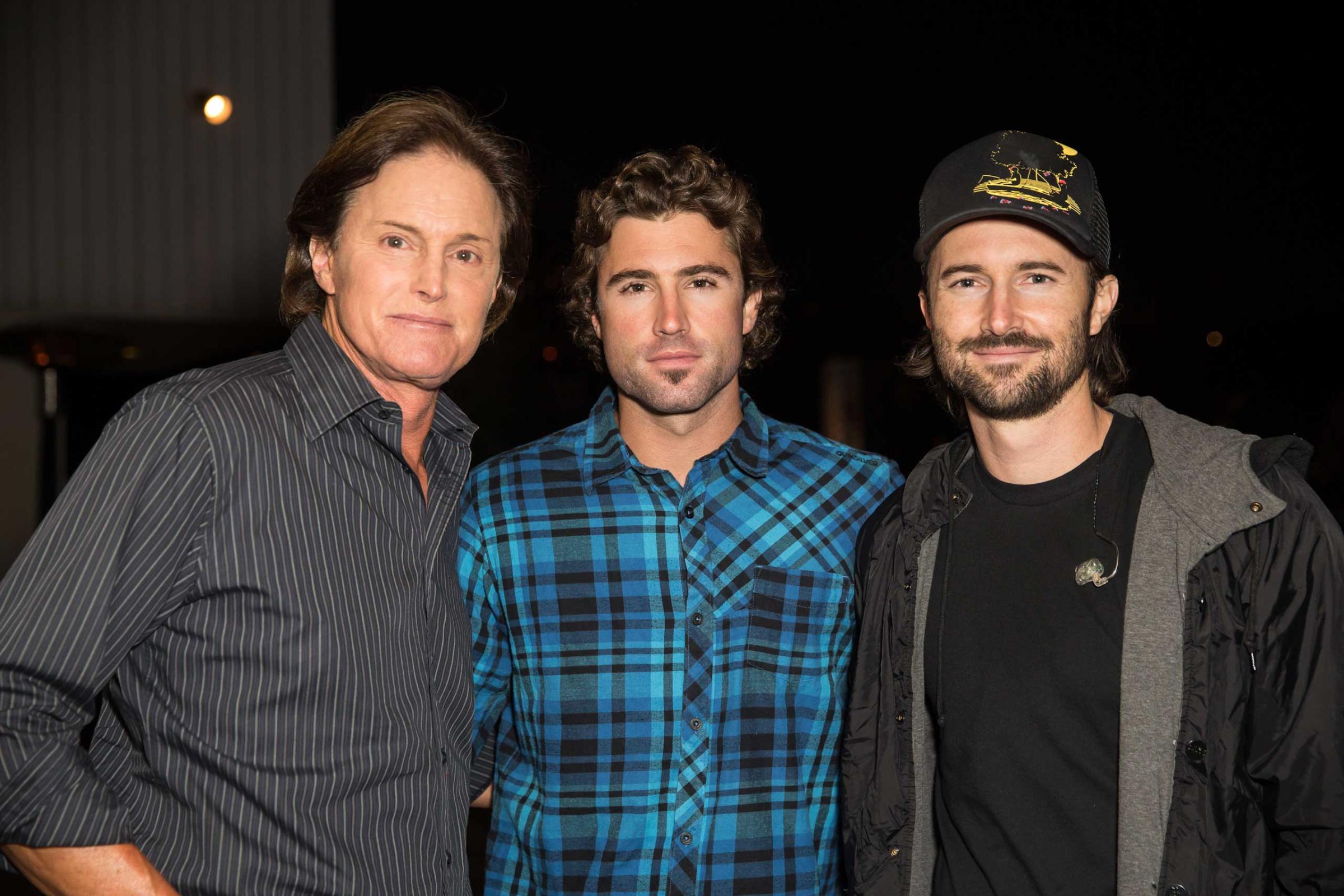

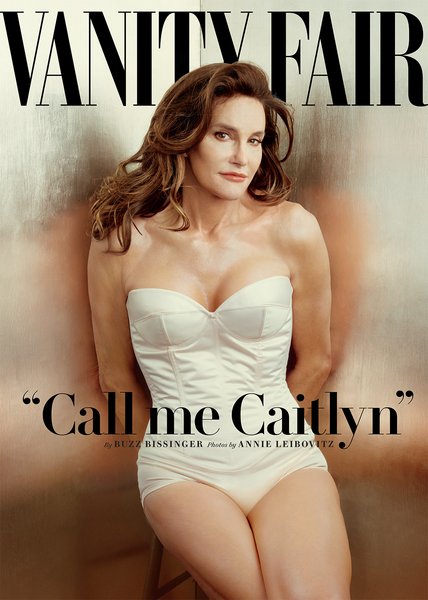

After Caitlyn Jenner, formerly Bruce Jenner, appeared on the cover of Vanity Fair, she became arguably the most visible transgender person in the world. It’s nearly impossible to go to the grocery store or CVS without seeing her face on every tabloid cover. And if you’re seeing her everywhere, that means your kids are too, especially because of her connection to the Kardashians.

But how do you explain Jenner’s transition to your children when they ask why a man is becoming a woman? Here, experts weigh in on the best way to have the conversation with your children of all ages.

To start: Michael LaSala, associate professor of social work at Rutgers University and a family therapist, says before you talk to your kids about this, you need to think about it yourself. “Parents need to do a self-inventory as to how they feel about the topic and to get straight in their minds what their feelings and thoughts and ideas are about transgender issues in general,” he says. “It behooves parents to become as educated as possible on the topic before talking to their children about it.”

Elementary school: With elementary-age children, it’s best to keep the explanation very basic, says Dr. Elijah Nealy, a clinical social worker who specializes in the transgender community. “Sometimes children are born in little girls’ bodies but they know in their hearts that they’re really a boy,” Nealy explains. “And sometimes as they grow up a doctor can help them become a boy. Young elementary age kids don’t need any more explanation than that.” In fact, Nealy says that the conversations with the young children may actually be the easiest – “My experience has been that they are able to comprehend that often much more easily than adults.”

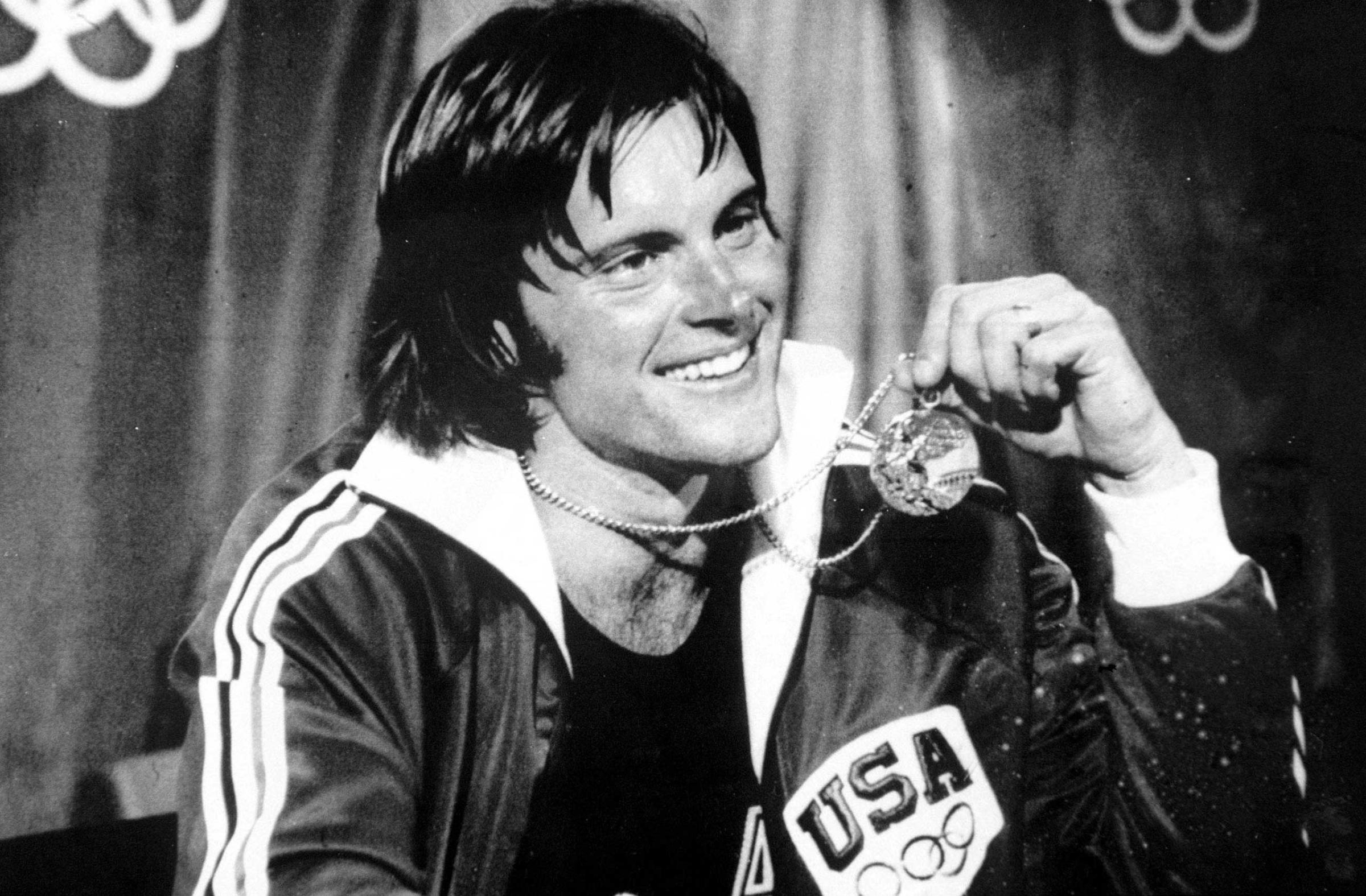

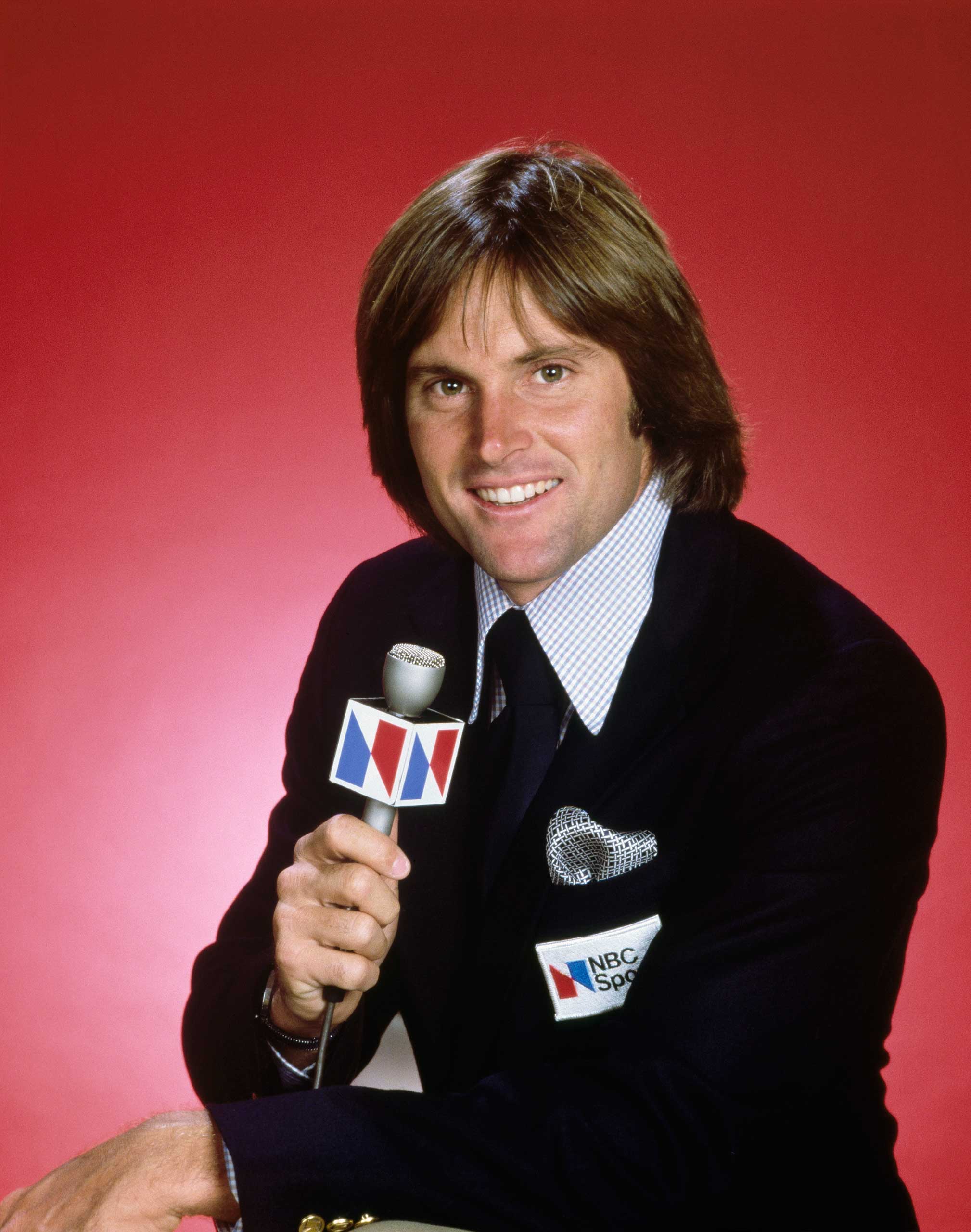

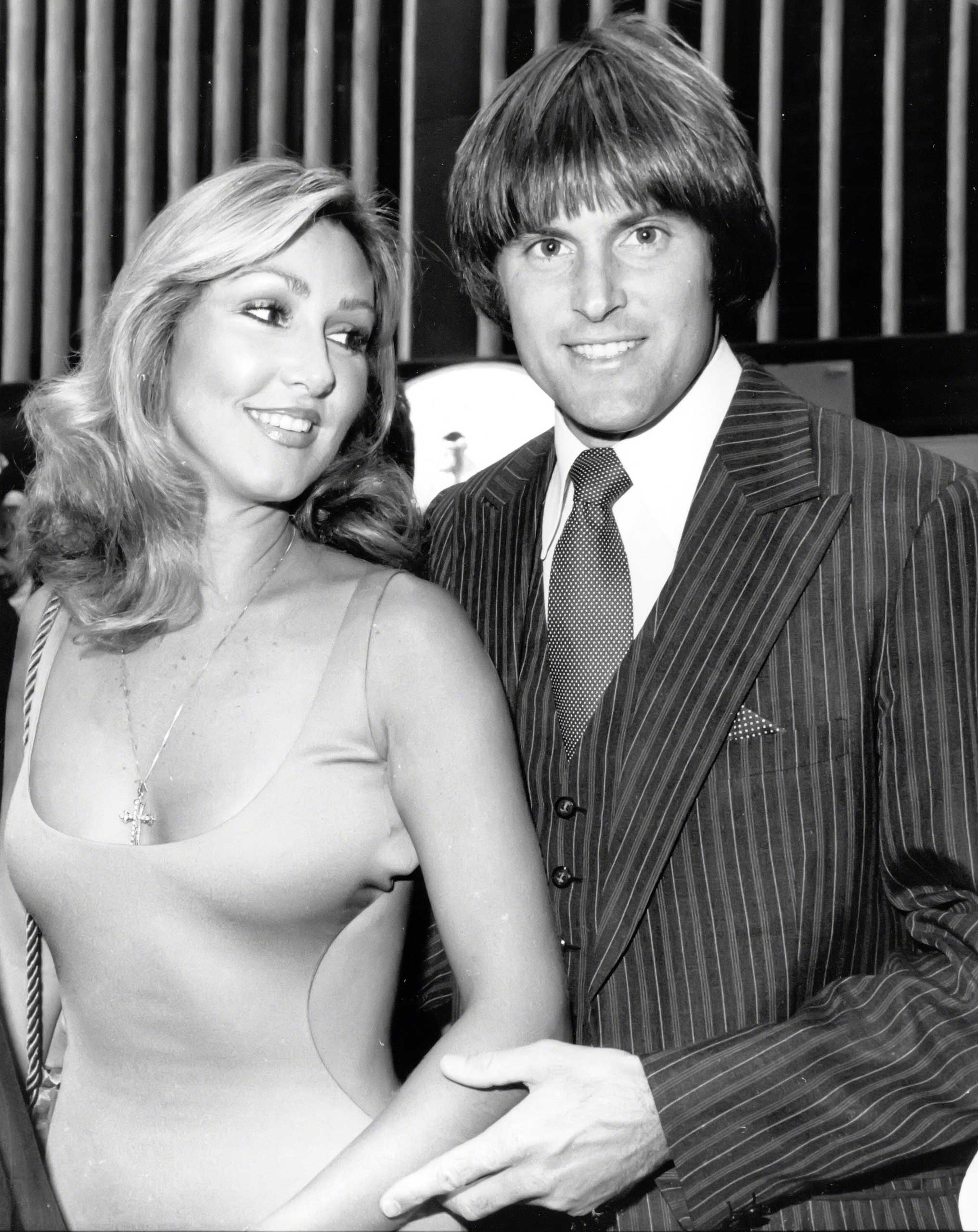

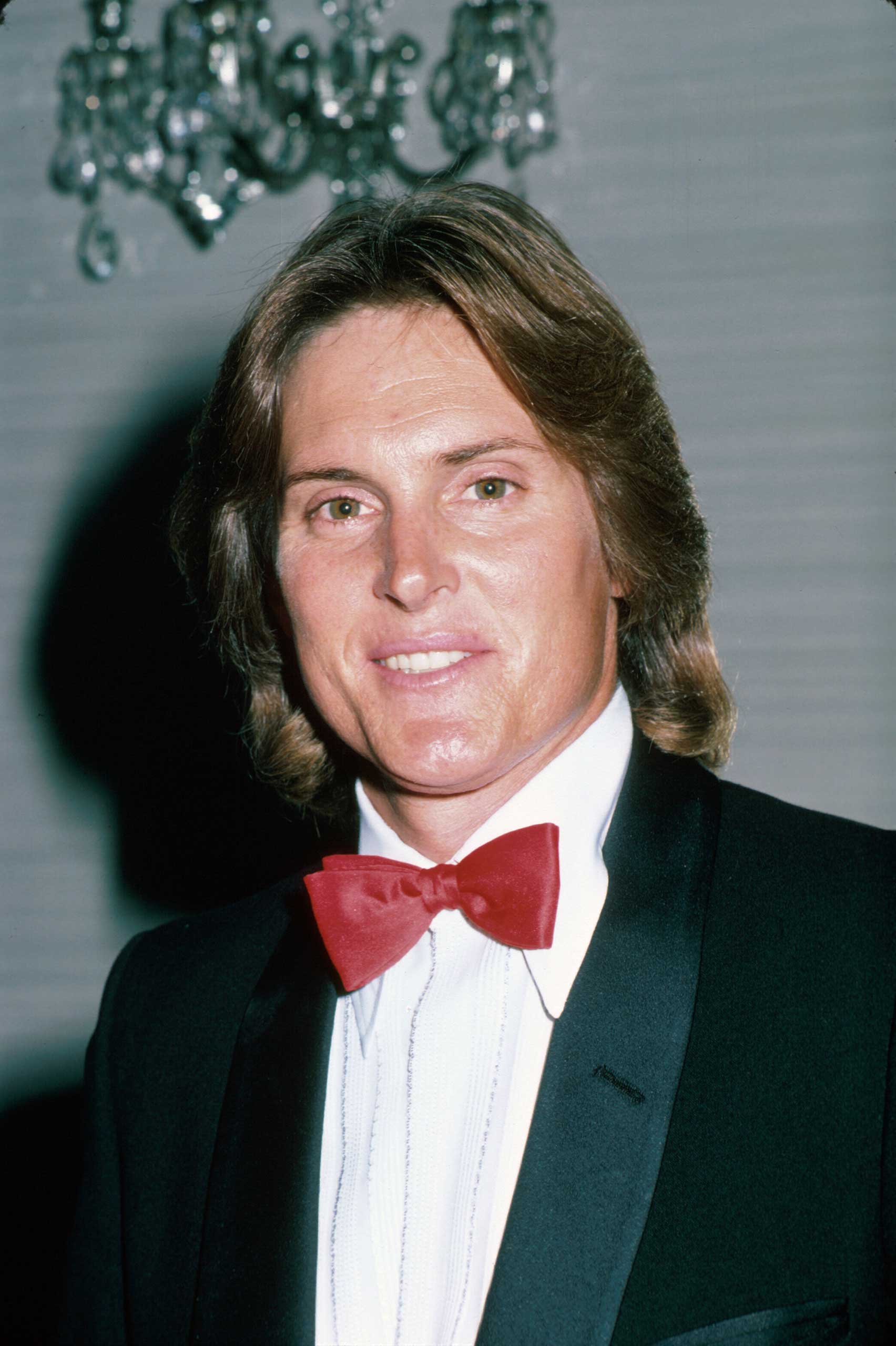

See The Life of Caitlyn Jenner

Middle school: Nealy says parents should approach the conversation with middle schoolers the same way they might with their elementary school children: sometimes people are born in the body of a boy but feel like they’re a girl. But to add more detail to the explanation, parents can start to teach their kids of this age about the difference between sex and gender. In general, sex is biological and gender is a personal identity. Nealy says you can explain this difference and the trans community to adolescents by saying, “For most people, the way they feel about themselves matches the sex that was assigned at birth, but for some people their own internal sense of themselves doesn’t match. Those people are called transgender, and they often transition so they can live in a way that fits.”

High school: If your kids are a bit older, around high school age, it may be the actual transition that they’re curious about, the ‘how’ of Bruce becoming Caitlyn. In that case, Nealy says you would need to make sure you had “accurate information in terms of transgender people being able to take hormones that help them look more like a man or a woman, or that they also might have surgeries.” LaSala cautions that kids of this age are more socialized and might be quicker to judgment or ridicule when they hear about a transgender person: “With older kids it may be important to have a talk about people and differences and trying to understand them rather than judging them and putting them down.”

Overall, Nealy says it’s best “to let the children guide the questions. I often start with the more basic information and then with a high school student would let them set the pace at which they want more information.” LaSala also has an overriding strategy for children of all ages: “Parents of all of those age groups,” he says, “need to be as straightforward and honest as possible.”

For more topical parenting tips, sign up for TIME’s free weekly parenting newsletter.

More Must-Reads from TIME

- Inside Elon Musk’s War on Washington

- Meet the 2025 Women of the Year

- The Harsh Truth About Disability Inclusion

- Why Do More Young Adults Have Cancer?

- Colman Domingo Leads With Radical Love

- How to Get Better at Doing Things Alone

- Cecily Strong on Goober the Clown

- Column: The Rise of America’s Broligarchy

Write to Tessa Berenson Rogers at tessa.Rogers@time.com